Introduction

Many people may view reflection as thinking about an event that has happened, but that is only part of it. Reflection can be about something that happened in the past, is happening now, or will/might happen in the future. For example, as a college student, you might reflect on a math test you took last month, how your current homework assignment is puzzling you, and how a math class might impact you next semester. It is important to see reflection as a continuing process because, as you will see in the next section, it is a valuable part of learning and growing in all disciplines and in all aspects of life.

Reflecting Across the Disciplines

If reflection seems like an act unique to your writing class, think about other courses and majors and how we see instances of reflection. Consider health fields and professions. Early in their educations, future nurses, doctors, and other health professionals are taught the importance of reflection in their work. People such as nurses and doctors regularly reflect on the condition of their patients, the care they provide, potential treatments, and future care. This type of thinking requires practice, which is why reflection is part of the courses these students take. For most people, it is not enough to just reflect in the mind. Writing allows health care professionals to keep a reflective log of patients (think about why nurses and doctors rely on those charts and patient records so much).

Further, it is important to think of learning as interconnected, and reflection may allow a space for connections to happen:

- Students in Mathematics may reflect on previous problems they have solved to help them think about pathways to tackle a more complex problem.

- Students in Economics may reflect on a simple economic model to help make more sense of complicated information.

- Students in Education may reflect on their growing knowledges of technology to help lay out innovative lesson plans for the classrooms of the future.

All of these are examples of how we use existing knowledge to learn more. In the discipline of Writing Studies, scholar Kathy Yancey posits that reflection is “a means of going beyond the text to include a sense of the ongoing conversations that texts enter into”.[1] In other words, your knowledge doesn’t exist in a vacuum, and this is true for all subjects. When you write, you seek to advance the knowledge of you and your readers, so reflecting on where what you are writing fits into what already has been written is meaningful.

Reflective Writing Frameworks

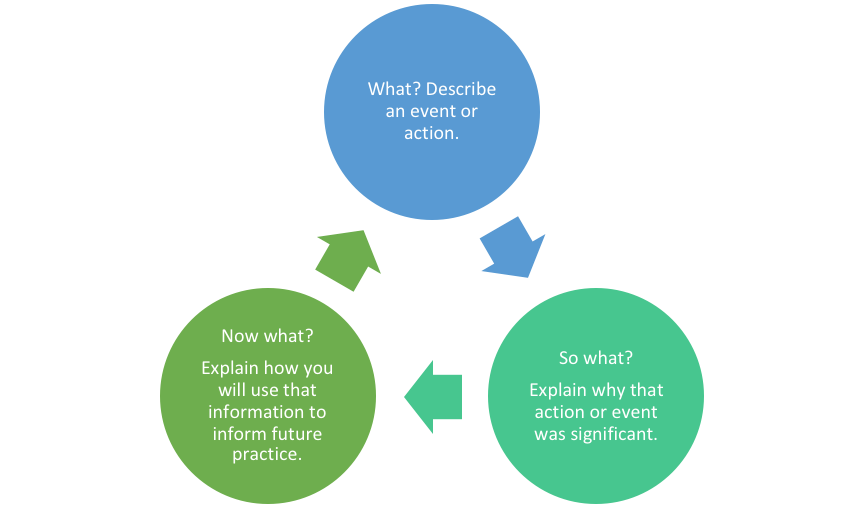

Researchers have developed several different frameworks or models for how reflective writing can be structured. John Driscoll[1] used Terry Borton’s[2] three stem questions to devise The Borton Framework pictured below.

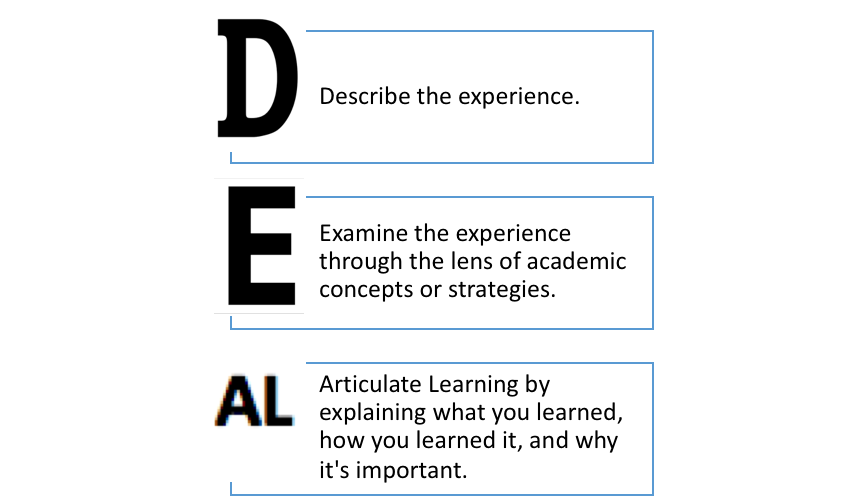

The DEAL model[3] structures reflective writing through a three-stage approach of description, examination, and articulation of learning.

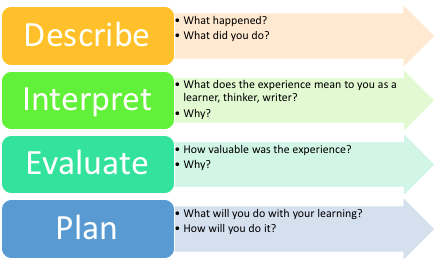

The DIEP model (Boud, Keogh & Walker,1985) incorporates aspects of both the Borton and DEAL frameworks with its emphasis on significance and future action.

Each of the models speaks to the reflective writer’s tasks: briefly describing an event or experience; analyzing the significance and value of the experience in terms of larger theory or practice; and forecasting how the learning might be useful in other situations.

Reflective Writing: A Process

1st Step: Review the Assignment

As with any writing situation, the first step in writing a reflective piece is to clarify the task. Reflective assignments can take many forms, so you need to understand exactly what your instructor is asking you to do. Some reflective assignments are short, just a paragraph or two of unpolished writing. Usually the purpose of these reflective pieces is to capture your immediate impressions or perceptions. For example, your instructor might ask you at the end of a class to write quickly about a concept from that day’s lesson. That type of reflection helps you and your instructor gauge your understanding of the concept.

Other reflections are academic essays that can range in length from several paragraphs to several pages. The purpose of these essays is to critically reflect on and support an original claim(s) about a larger experience, such as an event you attended, a project you worked on, or your writing development. These essays require polished writing that conforms to academic conventions, such as articulation of a thesis and substantive revision. They might address a larger audience than you and your instructor, including, for example, your classmates, your family, a scholarship committee, etc.

It’s important, before you begin writing, that you can identify the assignment’s purpose, audience, intended message or content, and requirements. If you can’t, ask your instructor for clarification.

2nd Step: Generate ideas for content

Refer to the Borton, DIEL, and DIEP models as you generate ideas for your writing. To meet the tasks identified in those models you might consider things like:

- Recollections of an experience, assignment, or course

- Ideas or observations made during that event

- Questions, challenges, or areas of doubt

- Strategies employed to solve problems

- A-ha moments linking theory to practice or learning something new

- Connections between this learning and prior learning

- New questions that arise as a result of the learning or experience

- New actions taken as a result of the learning or experience

3rd Step: Organize content

The Borton, DEAL, and DIEP frameworks can help you consider how to organize your content. Remember that your reflection will generally include descriptive writing, followed by analysis and interpretation, followed by consideration of significance for future action. That pattern might be developed once throughout a short piece or repeated several times in an academic reflective essay.

When writing an academic reflection essay (as opposed to a short reflection), you’ll need to devise and support a thesis. That thesis should be an interpretive or evaluative claim, or series of claims, that moves beyond obvious statements (such as, “I really enjoyed this project”) and demonstrates you have come to a deeper understanding of what you have learned and how you will use that learning. For example, the thesis below appeared in an end-of-semester reflection essay, written in response to an assignment asking students to consider their writing progress. Notice that the student makes a focused, interpretive claim that can be supported throughout her essay with evidence from her own writing.

Placement

A word about thesis placement: Because a reflection essay combines personal perception with academic convention, the thesis does not necessarily appear in the introduction. Many writers build to the thesis in the conclusion of their essays. You should place the thesis where it is most effective based on the essay’s structure.

And speaking of structure, there is no one-size-fits-all organization pattern for an academic reflection essay. Some writers introduce the subject, follow the introduction with a series of reflections, and then move to an interpretive close. Others establish a chronology of events, weaving the implications of those events throughout. Still others articulate a series of major points, supporting those points with evidence. You should craft an organizational structure that best fits your distinctive ideas and observations.

However you choose to organize an academic reflection essay, you’ll need to support your claims with evidence. Evidence is defined broadly in an academic reflection, so it might include such things as anecdotes, examples, relevant material from a course or outside sources, explanations of logic or decision-making, definitions, speculations, details, and other forms of non-traditional evidence. In the example below, notice how the writer uses her decision to limit the scope of a project as evidence to support her claim.

4th Step: Draft, Revise, Edit, Repeat

A single, unpolished draft may suffice for short, in-the-moment reflections. Longer academic reflection essays will require significant drafting, revising, and editing. Whatever the length of the assignment, keep this reflective cycle in mind:

- briefly describe the event or action;

- analyze and interpret events and actions, using evidence for support;

- demonstrate relevance in the present and the future.

Summary

Reflective writing is a balancing act with many factors at play: description, analysis, interpretation, evaluation, and future application. Reflective writers must weave their personal perspectives with evidence of deep, critical thought as they make connections between theory, practice, and learning.

Sources:

Driscoll J (1994) Reflective practice for practise – a framework of structured reflection for clinical areas. Senior Nurse 14 (1):47–50

Ash, S.L, Clayton, P.H., & Moses, M.G. (2009). Learning through critical reflection: A tutorial for service-learning students (instructor version). Raleigh, NC.

Boud, D.; Keogh, R.; Walker, D. (Eds) (1985) Reflection: turning experience into learning. London: Kogan Page

Yancey, Kathleen Blake (1998). Reflection in the Writing Classroom. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press.

“Reflection as a Continuum.” By: Guy Krueger|University of Mississippi. Retrieved from: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/olemiss-writing100/chapter/reflection-as-a-continuum/Licensed under: CC-BY-SA

“Frameworks for Reflective Writing.” By Lumen Learning UM RhetLab. Retrieved from: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/olemiss-writing100/chapter/frameworks-for-reflective-writing/ Licensed under: CC-BY-SA