Identifying Detracting or Redundant Details

Introduction

The more succinct your writing is without compromising clarity, the more your reader will appreciate your writing. The first trick to producing high quality writing is to really want to make every word count and to see excess words as grotesque indulgence. So, pretend that words are expensive. If you had to pay a cent of your own money for every character you wrote in a document that you had to print 1,000 copies of, you would surely adopt a frugal writing style. You would then see that adding unnecessary words is doubly wasteful because time is money. Time spent writing or reading tiresome pap is time you and your reader could spend making money doing other things. Terse, to-the-point writing is both easier to write and easier to read than insufferable rambling. After putting yourself in a frugal frame of mind that detests an excessively wordy style, follow the practical advice in the subsections below to evaluate places to trim your writing effectively.

Trimming Your Essay

The first practical step towards trimming your document is a large-scale purge of whatever doesn’t contribute to the purpose you set out to achieve. The order is important because you don’t want to do any fine-tooth-comb proof-editing on anything that you’re just going to delete anyway. This is probably the most difficult action to follow through on because it means deleting large swaths of writing that may have taken some time and effort to compose. You may even have enjoyed writing them because they’re on quite interesting sub-topics. If they sidetrack readers, whose understanding of the topic would be unaffected (at best) or (worst) overwhelmed by their inclusion, those sentences, paragraphs, and even whole sections simply must go. Perhaps save them in an “outtakes” document if you think you can use them elsewhere. Otherwise, like those who declutter their apartment after reading Marie Kondo’s The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up (2014), the release that follows such a purge can feel something like enlightenment. Highlight, delete, and don’t look back.

DELETE LONG LEAD-INS

The next-biggest savings come from deleting lead-ins that you wrote to gear up towards your main point. In ordinary speech, we use lead-ins as something like throat-clearing exercises. In writing, however, these are useless at best because they state the obvious. At worst, lead-ins immediately repulse the reader by signalling that the rest of the message will contain some time-wasting verbiage. If you see the following crossed-out expressions or anything like them in your writing, just delete them:

- I’m Jerry Mulligan and I’m writing this email to ask you to please consider my application for a co-op position at your firm.

- You may be interested to know that you can now find the updated form in the company shared drive.

- To conclude this memo, we recommend a cautious approach to using emojis when texting clients, and only after they’ve done so first themselves.

In the first example, the recipient sees the name of the sender before even opening their email. It’s therefore redundant for the sender to introduce themselves by name and say that they wrote this email. Likewise, in the third example, the reader can see that this is the conclusion if it’s the last paragraph, especially if it comes below the heading “Conclusion.” In each case, the sentence really begins after these lead-in expressions, and the reader misses nothing in their absence. Delete them.

PARE DOWN UNNECESSARILY WORDY PHRASES

We habitually sprinkle long stock phrases into everyday speech because they sound fancy merely because they’re long and sometimes old-fashioned, as if length and long-time use grants respectability (it doesn’t). These phrases look ridiculously cumbersome when seen next to their more concise equivalent words and phrases, as you can see in Table 5.1.4.3 below. Unless you have good reason to do otherwise, always replace the former with the latter in your writing.

TABLE 5.1.4.3: REPLACE UNNECESSARILY WORDY PHRASES WITH 1-2 WORD EQUIVALENTS

| Replace These Wordy Phrases | with These Concise Equivalents |

|---|---|

| at this present moment in time | now |

| in any way, shape, or form | in any way |

| pursuant to your request | as requested |

| thanking you in advance | thank you |

| in addition to the above | also |

| in spite of the fact that | even though / although |

| in view of the fact that | because / since |

| are of the opinion that | believe that / think that |

| afford an opportunity | allow |

| despite the fact that | though |

| during the time that | while |

| due to the fact that | because / since |

| at a later date/time | later |

| until such time as | until |

| in the near future | soon |

| fully cognizant of | aware of |

| in the event that | if |

| for the period of | for |

| attached hereto | attached |

| each and every | all |

| in as much as | because / since |

| more or less | about |

| feel free to | please |

Again, the reader misses nothing if you use the words and phrases in the second column above instead of those in the first. Also, concise writing is more accessible to readers who are learning English as an additional language.

DELETE REDUNDANT WORDS

Like the wordy expressions in Table 5.1.4.3 above, our speech is also riddled with redundant words tacked on unnecessarily in stock expressions. These prefabricated phrases strung mindlessly together aren’t so bad when spoken because talk is cheap. In writing, however, which should be considered expensive, they make the author look like an irresponsible heavy spender. Be on the lookout for the expressions below so that you are in command of your language. Simply delete the crossed-out words in red if they appear in combination with those in blue:

- absolutely essential (you can’t get any more essential than essential)

- future plans (are you going to make plans about the past? plans are always future)

- small in size (the context will determine that you mean small in size, quantity, etc.)

- refer back to

- in order to (only use “in order” if it helps distinguish an infinitive phrase, which begins with “to,” from the preposition “to” appearing close to it)

- each and every or each and every (or just “all,” as we saw in Table 5.1.4.3 above)

- repeat again (is this déjà vu?)

DELETE FILLER EXPRESSIONS AND WORDS

If you audio-record your conversations and make a transcript of just the words themselves, you’ll find an abundance of filler words and expressions that you could do without and your sentences would still mean the same thing. A few common ones that appear at the beginning of sentences are “There is,” “There are,” and “It is,” which must be followed by a relative clause starting with the relative pronoun that or who.

Consider the following, for example:

1. (Before) There are many who want to take your place. (After) Many want to take your place.

2. (Before) There is nothing you can do about it.(After) You can do nothing about it.

3. (Before) It is the software that keeps making the error. (After) The software keeps erring.

In the first and third cases, you can simply delete “There are” and “It is,” as well as the relative pronouns “who” and “that” respectively, leaving the sentence perfectly fine without them. In the second case, deleting “There is” requires slightly reorganizing the word order, but otherwise requires no additional words to say the very same thing. In each case, you save two or three words that simply don’t need to be there.

Other common filler words include the articles a, an, and the, especially in combination with the preposition of. You can eliminate many instances of of the simply by deleting them and flipping the order of the nouns on either side of them.

(Before) technology of the future (After) future technology

Obviously, you can’t do this in all cases (e.g., changing “first of the month” to “month first” makes no sense). When proofreading, however, just be on the lookout for instances where you can.

The definite article the preceding plural nouns is also an easy target. Try deleting the article to see if the sentence still makes sense without it.

(Before) The shareholders unanimously supported the initiative.

(After) Shareholders unanimously supported the initiative.

Though the above excess words seem insignificant on their own, they bulk up the total word count unnecessarily when used in combination throughout a large document. They are like dog food fillers such as “powdered cellulose” (a.k.a. sawdust). They provide no nutritive value, but manufacturers add them to charge you more for the mere volume they add to the product. Please don’t cut your writing with filler.

DELETE NEEDLESS ADVERBS

Streamline your writing by purging the filler adverbs that you pepper your conversational speech with. In writing, these add little meaning. Recall that adverbs are words that explain verbs (like adjectives do nouns) and typically, but not always, end in -ly. Some of the most common intensifying adverbs include the following:

actually

basically

completely

definitely

extremely

fairly

fully

greatly

hugely

literally

quite

rather

really

somewhat

terribly

totally

very

wholly

Perhaps the worst offender in recent years has been literally, which people overuse and often misuse when they mean “figuratively” or even “extremely,” especially when exaggerating. Saying, “I’ve literally told you a million times not to exaggerate” misuses literally (albeit ironically in this case) because telling someone not to exaggerate a million times would literally take about 20 days if you did nothing but repeat the phrase constantly all day every day without sleeping. That’s not going to happen. If you say, “I’m literally crazy for your speaking style,” you just mean “I’m thrilled by your speaking style.” Using “literally” in this case is just babbling nonsense.

If you find yourself slipping in any of the above adverbs in your writing, question whether they need to be there. (In the case of the previous sentence, leaving out “really” before “need” doesn’t diminish the impact of the statement much.) Consider the following sentence:

(Before) Basically, you can’t really do much to fully eliminate bad ideas because they’re quite common.

(After) You can’t do much to eliminate bad ideas because they’re so common.

FAVOUR SHORT, PLAIN WORDS AND USE JARGON SELECTIVELY

If you pretend that every character in each word you write costs money from your own pocket, you would do what readers prefer: use shorter words. The beauty of plain words is that they are more understandable and draw less attention to themselves than big, fancy words while still getting the point across. This is especially true when your audience includes ESL readers. Choosing shorter words is easy because they are often the first that come to mind, so writing in plain language saves you time in having to look up and use bigger words unnecessarily. It also involves vigilance in opting for shorter words if longer jargon words come to mind first.

Obviously, you would use jargon for precision when appropriate for your audience’s needs and your own. You would use the word “photosynthesis,” for instance, if (1) you needed to refer to the process by which plants convert solar energy into sugars and (2) you know your audience knows what the word means. In this case, using the big, fancy jargon word achieves a net savings in the number of characters because it’s the most precise term for a process that otherwise needs several words. Using jargon words merely to extend the number of characters, however, is a desperate-looking move that your instructors and professional audiences will see through as a time-wasting smokescreen for a lack of quality ideas.

Table 5.1.4.7 below lists several polysyllabic words (those having more than one syllable) that writers often use when a shorter, more plain and familiar word will do just as well. There’s a time and place for fancier words, such as when formality is required, but in routine writing situations where there’s no need for them, always opt for the simple, one- or two-syllable word.

TABLE 5.1.4.7: FAVOUR PLAIN, SIMPLE WORDS OVER POLYSYLLABIC WORDS

| Big, Fancy Words | Short, Plain Options |

|---|---|

| advantageous | helpful |

| ameliorate | improve |

| cognizant | aware |

| commence | begin, start |

| consolidate | combine |

| deleterious | harmful |

| demonstrate | show |

| disseminate | issue, send |

| endeavour | try |

| erroneous | wrong |

| expeditious | fast |

| facilitate | ease, help |

| implement | carry out |

| inception | start |

| leverage | use |

| optimize | perfect |

| proficiencies | skills |

| proximity | near |

| regarding | about |

| subsequent | later |

| utilize | use |

Source: Brockway (2015)

The longer words in the above table tend to come from the Greek and Latin side of the English language’s parentage, whereas the shorter words come from the Anglo-Saxon (Germanic) side. When toddlers begin speaking English, they use Anglo-Saxon-derived words because they’re easier to master, and therefore recognize them as plain, simple words throughout their adult lives.

Definitely don’t use longer words when they’re grammatically incorrect. For instance, using reflexive pronouns such as “myself” just because it sounds fancy instead looks foolish when the subject pronoun “I” or object pronoun “me” are correct.

(Before) Aaron and myself will do the heavy lifting on this project.

(After) Aaron and I will do the heavy lifting on this project.

(Before) I’m grateful that you contacted myself for this opportunity.

(After) I’m grateful that you contacted me for this opportunity.

The same goes for misusing the other reflexive pronouns “yourself” instead of “you,” “himself” or “herself” instead of “him” or “her,” etc. See Table 4.4.2a above for more on correct uses of pronouns.

Sometimes, you see short words rarely used in conversation being used in writing to appear fancy, but just look pretentious, such as “said” preceding a noun.

(Before) Call me if you are confused by anything in the said contract.

(After) Call me if you are confused by anything in the contract.

Usually, the context helps determine that the noun following “said” is the one mentioned earlier, making “said” an unnecessary, pompous add-on. Delete it or use the demonstrative pronouns “this” or “that” if necessary to avoid confusion.

Finally, don’t fall into the trap of thinking that a simple style is the same as being simplistic. Good writing can communicate complex ideas in simple words just like bad writing can communicate simple ideas with overly complex words. The job of the writer in professional situations is to make smart things sound simple. Be wary of writing that makes simple things sound complex. You probably don’t want what it’s selling.

SIMPLIFY VERBS

Yet another way that people overcomplicate their writing involves expressing the action in as many words as possible, such as by using the passive voice (see §4.3.4 above), continuous tenses, and nominalizations. We’ve already seen how the passive voice rearranges the standard subject-verb-object word order so that, by going object-verb-subject, an auxiliary verb (form of the verb to be) and the preposition by must be added to say what an active voice sentence says without them. Consider the following sentences, for instance:

(Before) The candidate cannot be supported by our membership.

(After) Our members cannot support the candidate.

Here, the active-voice construction on the right uses two fewer words to say the same thing. Though we saw in §4.3.4 that there certainly are legitimate uses of the passive voice, overusing the passive voice sounds unnatural and appears as an attempt to extend the word count or sound more fancy and objective. Because the passive voice is either more wordy or vague than the active voice, however, readers prefer the latter most of the time and so should you.

Another common annoyance to busy readers is using continuous verb forms instead of simple ones. The continuous verb form uses the participle form of the main verb, which means adding an -ing ending to it, and adds an auxiliary verb (form of the verb to be, which differs according to the person and number) to determine the tense (past, past perfect, present, future, future perfect, etc.). In the table below, you can see how cumbersome continuous forms are compared with simple ones.

TABLE 5.1.4.8: FAVOUR SIMPLE VERB FORMS INSTEAD OF CONTINUOUS FORMS

| Continuous Verb Forms | Simple Verb Forms |

|---|---|

| I was writing a letter to her. | I wrote a letter to her. |

| I had been writing a letter to her. | I had written a letter to her. |

| I have been writing a letter to her. | I have written a letter to her |

| I would have been writing a letter to her. | I would have written a letter to her. |

| I am writing a letter to her. | I write a letter to her. |

| I would be writing a letter to her. | I would write a letter to her. |

| I will be writing a letter to her. | I will write a letter to her. |

| I will have been writing a letter to her. | I will have written a letter to her. |

There are certainly legitimate reasons for using continuous verb forms to describe actions stretching out over time. In the case of the present tense, saying, “I am considering my options” is more appropriate compared with “I consider my options” because you really are in the process of considering your options. In other tenses, however, people who use wordcount-extending strategies favour continuous verb forms because they think those forms sounds fancier. Overused or misused, however, such verb forms just annoy the reader by overcomplicating the language.

Yet another strategy for extending the wordcount with verbs is to turn the main action they describe into nouns, a process called nominalization. This involves taking a verb and adding a suffix such as -ant, -ent, -ion, -tion, -sion, -ence, -ance, or -ing, as well as adding forms of other verbs, such as to make or to give. Nominalization may also require determiners such as articles (the, a, or an) before the action nouns. Consider the following comparisons of nominalized-verb sentences with simplified verb forms:

| The committee had a discussion about the new budget constraints. | The committee discussed the new budget constraints. |

| We will make a recommendation to proceed with the investment option. | We will recommend proceeding with the investment option. |

| They handed down a judgment that the offer wasn’t worth their time. | They judged that the offer wasn’t worth their time. |

| The regulator will grant approval of the new process within the week. | The regulator will approve the new process within the week. |

| He always gives me advice on what to say to the media. | He always advises me on what to say to the media. |

| She’s giving your application a pass because of all the errors in it. | She’s passing on your application because of all the errors in it. |

You can tell that the above sentences where the simple verb drives the action are punchier and have greater impact than those that turn the action into a noun and thus require more words to say the same thing. Indeed, each of the verb-complicating, wordcount-extending strategies throughout this subsection is bad enough on its own. In combination, however, writing riddled with nominalization, continuous verb forms, and passive-voice verb constructions muddies writing with an insufferable multitude of unnecessary words.

The final trick to making your writing more concise is the Editor feature in your word processor. In Microsoft Word, for instance, you can set up the Spelling & Grammar checker to scan for all the problems above by following the procedure below:

| The committee had a discussion about the new budget constraints. | The committee discussed the new budget constraints. |

| We will make a recommendation to proceed with the investment option. | We will recommend proceeding with the investment option. |

| They handed down a judgment that the offer wasn’t worth their time. | They judged that the offer wasn’t worth their time. |

| The regulator will grant approval of the new process within the week. | The regulator will approve the new process within the week. |

| He always gives me advice on what to say to the media. | He always advises me on what to say to the media. |

| She’s giving your application a pass because of all the errors in it. | She’s passing on your application because of all the errors in it. |

You can tell that the above sentences where the simple verb drives the action are punchier and have greater impact than those that turn the action into a noun and thus require more words to say the same thing. Indeed, each of the verb-complicating, wordcount-extending strategies throughout this subsection is bad enough on its own. In combination, however, writing riddled with nominalization, continuous verb forms, and passive-voice verb constructions muddies writing with an insufferable multitude of unnecessary words.

The final trick to making your writing more concise is the Editor feature in your word processor. In Microsoft Word, for instance, you can set up the Spelling & Grammar checker to scan for all the problems above by following the procedure below:

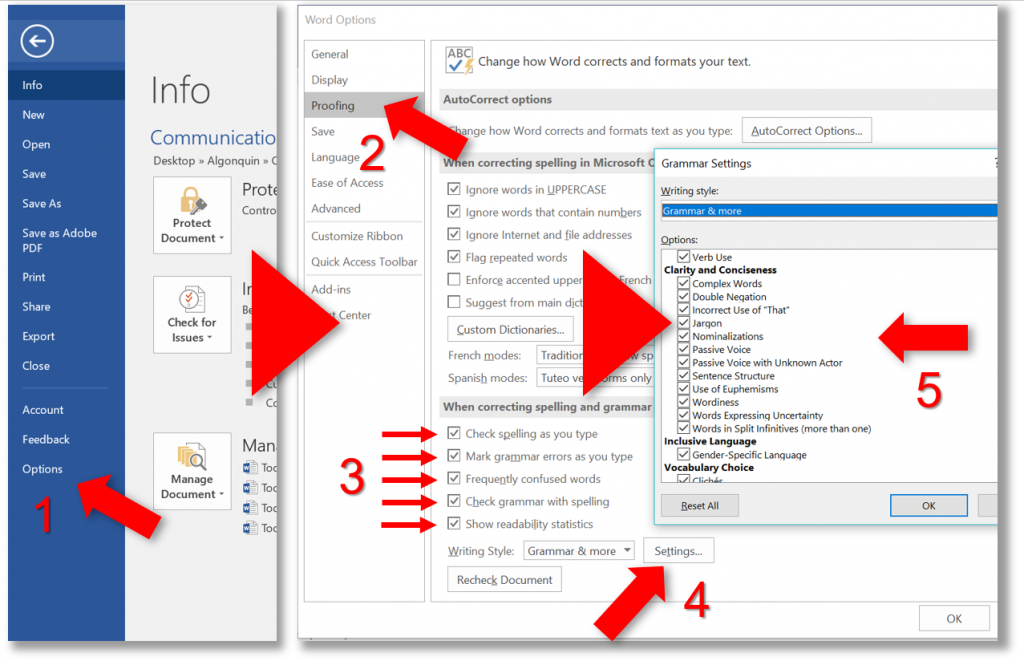

- Go to File (alt. + f) and, in the File menu, click on Options (at the bottom; alt. + t) to open the Word Options control panel.

- Click on Proofing in the Word Options control panel.

- Check all the boxes in the “When correcting spelling and grammar in Word” section of the Word Options control panel.

- Click on the Settings… button beside “Writing Style” under the check boxes to open the Grammar Settings control panel.

- Click on all the check boxes in the Grammar Settings control panel, as well as the Okay button of both this panel and the Word Options panel to activate.

- Go to the Review menu tab in the tool ribbon at the top of the Word screen and select Spelling & Grammar (alt. + r, s) to activate the Editor that will, besides checking for spelling and grammar errors, also check for all of the stylistic errors you checked boxes for in the Grammar Settings control panel.

When you finish running your grammar, style, and spellchecker through your document, a dialog box will appear showing readability statistics. Pay close attention to stats such as the average number of words per sentence and letters per word. If the former exceeds thirty and the latter ten, your writing might pose significant challenges to some readers, especially ESL. Do them a solid favour by breaking up your sentences and simplifying your word choices.

Summary

Rather than suck the life out of language by adding useless verbiage, make your writing like a paperclip. A paperclip is beautiful in its elegance. It’s so simple in its construction and yet does its job of holding paper together perfectly without any extra parts or mechanisms like staples need to fasten pages together and unfasten them. A paperclip does it with just a couple inches of thin, machine-bent wire. We should all aspire to make our language as elegant as a paperclip so that we can live life free of time-wasting writing.

Key Takeaway: Begin editing any document by evaluating it for the quality of its content, organization, style, and readability, then add to it, reorganize, and trim it as necessary to meet the needs of the target audience.

Sources:

“Communication at Work.” By Jordan Smith. Retrieved from: https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/communicationatwork/chapter/5-1-substantial-revisions/ Licensed under: CC-BY Adapted by The American Women’s College.