Teaching with KnowledgePath

Introduction to KnowledgePath

KnowledgePath (KP) is a key component of SOUL that modifies the content, presentation, and pace of learning and teaching based on each student’s performance and preference. KP empowers you to be a more effective educator who responds rapidly and in a more focused manner than ever before. Adaptive learning clarifies the sources of students’ struggles and which students have done the reading or not. Visuals in the KP system will position you to see very specific data about:

-

- How each student is performing on each and every topic in your course

- Who may need your assistance

- Who may be lagging behind schedule

- Who is working ahead of the curve

- Mastery levels, and their stated preference for content-type. In this way, KP uses Universal Design for Learning principles.

- Each KP assignment features a pretest to gauge students’ prior knowledge levels. Those who display mastery are able to work ahead in their learning. Struggling students, on the other hand, revisit content and can choose to see an alternative version of the content until they achieve mastery.

- The clear depiction of the mastery level also encourages our students to engage in metacognition by actively reflecting on how they are learning and achieving. They are thus empowered by the language built into their learning maps to reach out to their instructors for support on very specific topics.

What is your role in KP?

Your role in a KP course is different from teaching in a traditional online course. The teaching benefits of the KP system are predicated upon your accessing the system on a regular basis and conducting proactive interventions with your students. Remember: you no longer need to wait for a student to tell you they are struggling; you’ll see it right when they do and you’ll know exactly how to help!

How does KP relate to the rest of your course?

Several of our courses include KP, though not all do. If a course does have a KP component, typically there will be a KP assignment in each module. This adaptive assignment is meant to cover the foundational knowledge for the module, so it leads students to greater success on discussion posts and culminating assignments. You should encourage students to complete the KP assignment early in the module since its content is necessary to finish other work.

Accessing the KnowledgePath Content

To get started and to see the material in the course, follow these steps:

- Click on the Learning Map tab

- Select an activity

- Select view activity

Lessons may contain an introduction, main content which can include text, videos or interactive tools, questions, and a summary of the section. After the student reviews the material, the system will present approximately four (4) randomized questions on the material for which students must achieve, at a minimum, Emerging (light red) to unlock subsequent activities.

After the activity is completed, the system will guide the student on what to do next. It may suggest moving on (if they completed the activity successfully) or it may ask the student to revise their work because they did not demonstrate sufficient knowledge.

This section is just to make sure you understand that, as an instructor, you can always see the content the student sees, but the questions are randomized so you cannot easily view the questions, especially as they can be different for different students.

Cross-curricular Mapping and Prerequisite Knowledge

One key feature of KnowledgePath is it’s ability to incorporate mapping of concepts across and within the curriculum. For example, ENG-114 Critical Reading and Response introduces students to essential reading and writing concepts. Since these concepts are prerequisites to content covered in higher-level English courses, these activities may be linked or included in other courses. Students need to understand they still need to know these concepts to be successful, and in those instances, we recommend that they review the material even if their learning maps show that they have completed the assignment previously. You might also remind students that their grade(s) will be reflective of what they see on the map and that they have the opportunity to revise their work to improve their score.

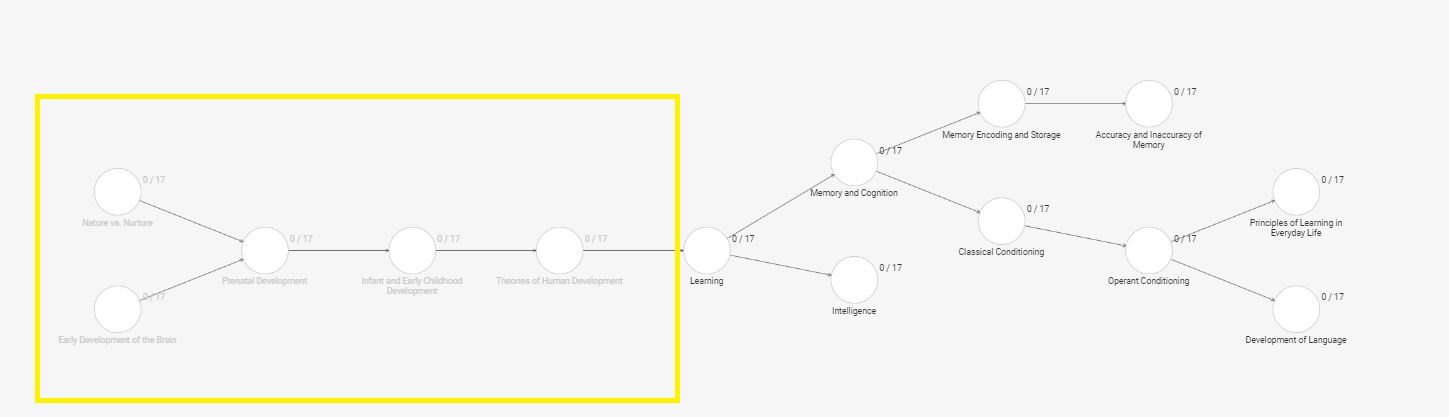

The example below shows a section on the left that is grayed out. This prerequisite knowledge was completed from an earlier assignment or course, but it has been included because it is directly linked to the content being covered in the current activity. The completed activities are shown so that students can reference them as needed.

Cross-curricular mapping offers all students access to the necessary materials to aid in their success in their class. By linking concepts and prerequisite knowledge, students are provided the opportunity for refreshers on specific concepts covered in other courses that may prove beneficial to the material being covered.

Understanding the Instructor Tabs

To Do Tab

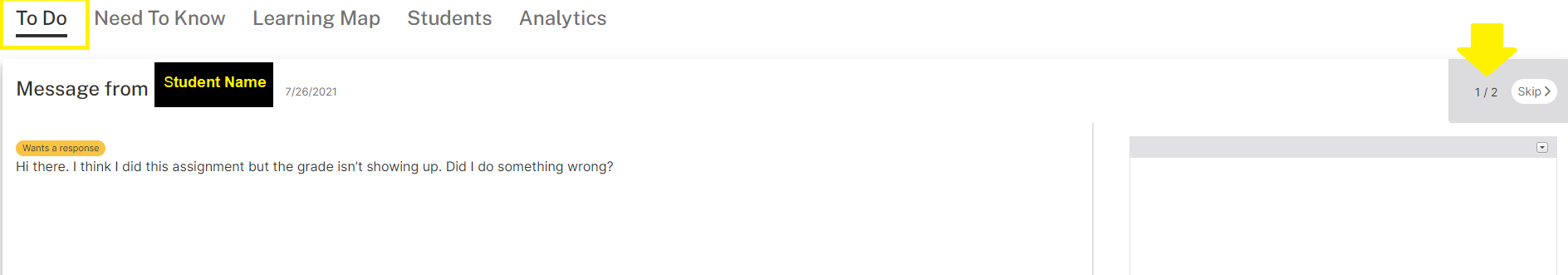

The “To Do” tab is very unique because it does not always show as a tab unless you have something “to do.” Items that may appear on this list include grades that need to be submitted that have not yet been synced, messages from students in need of a response, or queried questions that need to be reviewed.

The top yellow arrow points to the number of items in your “To Do” queue. Identifying student information has been blocked for these examples; however, please note that the student’s name would appear in place of the black box.

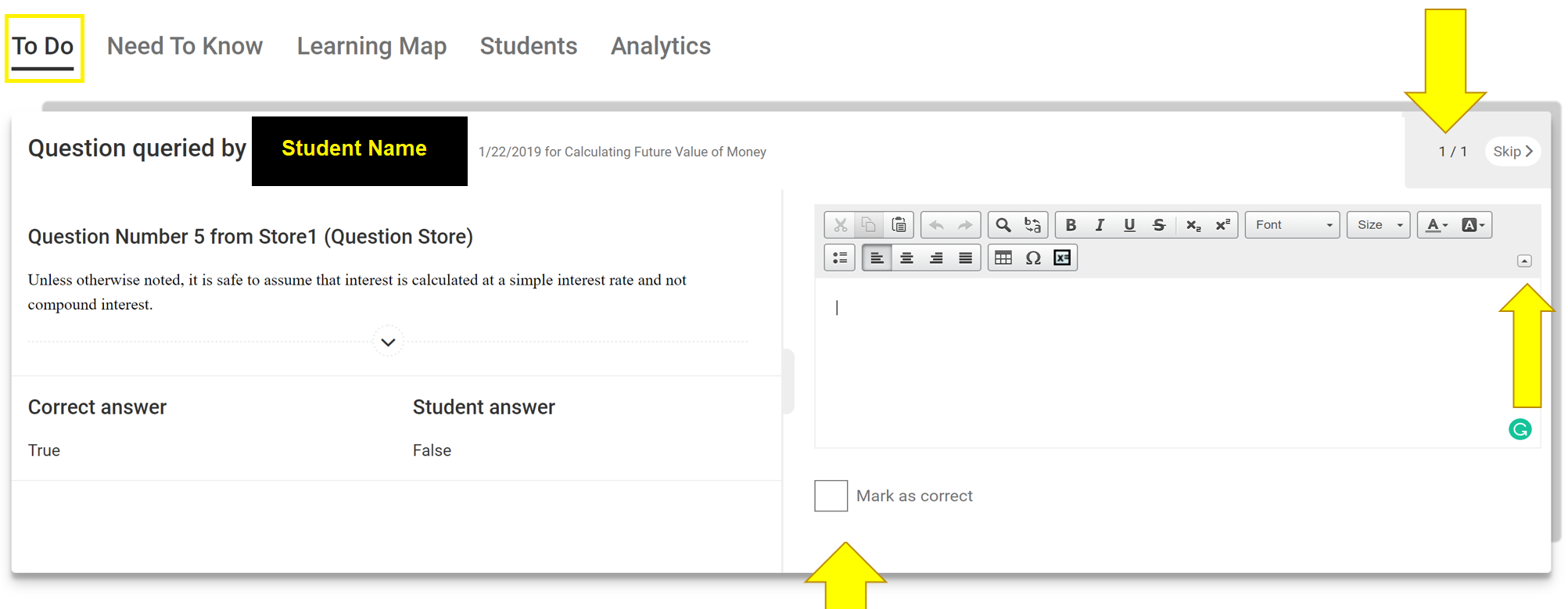

Queried Questions

Queried questions are an essential part of the instructional process in KnowledgePath. These are questions that students have flagged because they believe they answered the question correctly and were marked incorrect. This can be true both through the system and human errors, but just because a student perceives a response to be correct, it does not automatically mean they are correct. But, it does warrant our investigation and correction when appropriate, or an explanation to clarify for the student.

A queried question will automatically show in your “To Do” section as part of a queue for you to complete. The Toolbox acts as an aggregator of the information for display in this one area. It is also available for you to share with your Academic Program Director so they can allow for the correction of the content. You can search for questions by selecting Show Each Question Asked or Show Each Question Type, or you can filter by Date Range and Status.

To query a question, students may reach out to you in multiple ways, but querying a question through the system is the recommended practice. As you can see, there is an arrow pointing to a box that can be checked “Mark as Correct.” The final yellow arrow points to the box that can expand the text box to allow for commenting. If you determined that the queried question/answer is, in fact, correct, it is recommended that you provide feedback to students to explain why.

Important: If you find that a question needs to be adjusted, you must reach out to your Program Director to notify them of the issue. The Instructional Design team can then make the global change to the content so that the problem does not continue in future courses.

Need to Know Tab

The Need to Know tab will provide you with some information to help determine the type(s) of interventions you might consider for your individual students or for the class as a whole. This tab will notify you of the number of students who have not yet started the activity, and it will provide you with an easy link to send a message to remind those students to get started.

It will also notify you of those students who have not yet completed their Determined Knowledge. Again, a link to the messenger is provided so that you can easily send a reminder to those students.

This section will also highlight specific problems with certain content areas. It will let you know where students are struggling so that you can reach out to offer support. If multiple students are struggling with the same content, you might also considering posting a video or supplemental materials in Canvas to help everyone.

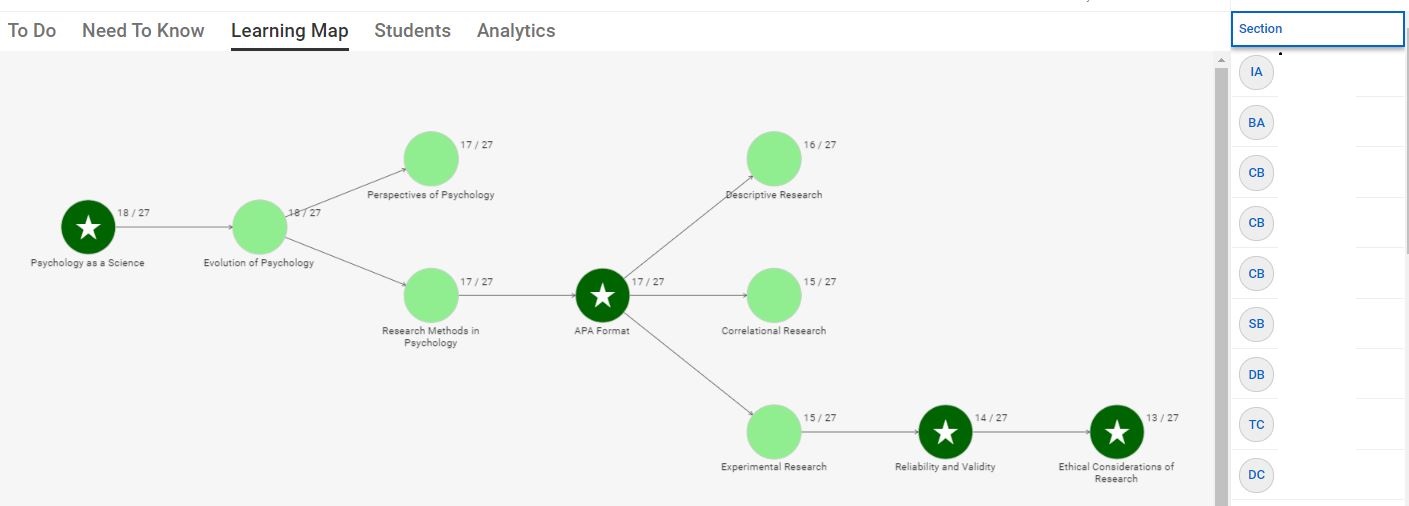

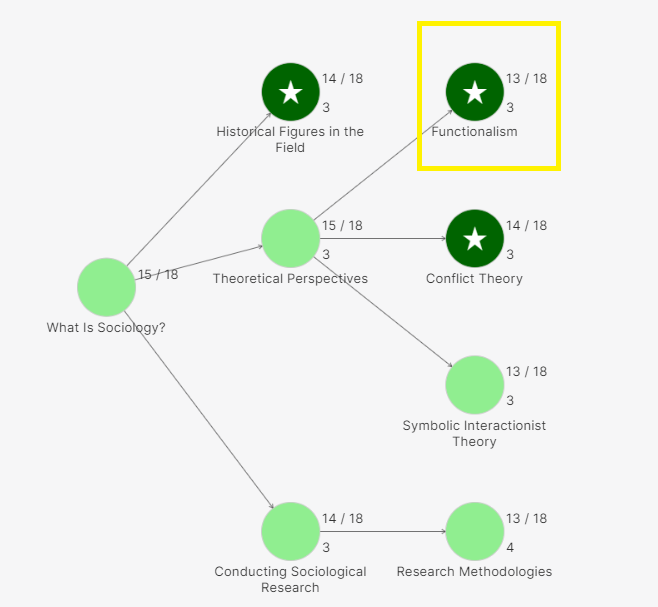

Learning Map

The Learning Map tab will provide you with an image of the learning map, as well as a summary of how many students have completed each activity, and the section level of mastery. In the example below, you will see that 13 out of 18 students completed the activity on Functionalism.

If you were to hover over the activity, it would provide you with the section level competency. In this example, this course scored 93.69%, which is considered exemplary on the scoring scale.

If you were to hover over the activity, it would provide you with the section level competency. In this example, this course scored 93.69%, which is considered exemplary on the scoring scale.

- Exemplary (dark green) is when you score 90% or greater on an activity. Another important aspect of grading, we want you to understand, when you score in the Exemplary (dark green) range you will receive 100% for that activity, this is because when you score greater than 90% on an activity it will be rounded to 100%.

- Mastery (light green) is when you score from 80% to 89% on an activity.

- Proficient (yellow) is when you score from 70%-79% on an activity.

- Emerging (light red) is when you score from 50%-69% on an activity.

- Does Not Meet (dark red) is when you score from 0% to 49%. Your score does not meet expectations and you will not be able to proceed to future activities.

Students Tab

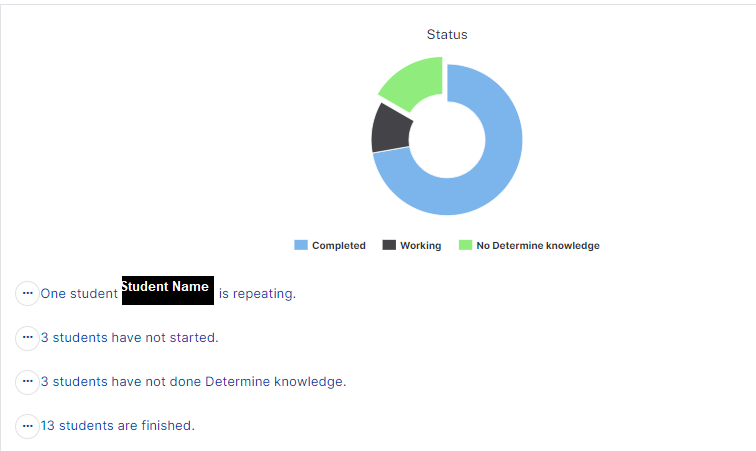

The Students tab will provide you with an overall summary of student performance. Several visuals will be presented, along with bulleted highlights for your review. For example, one chart will show the status of a particular activity, as shown below.

Other helpful information provided in this tab include:

- Student Specific Information

- Last time student worked in KnowledgePath

- Time spent on the activity

- Knowledge Covered (number of activities completed)

- Knowledge State (mastery level of content)

- Composite Score

- Class Specific Information

- Knowledge Covered (number of activities completed)

- Knowledge State (mastery level of content)

- Number of students working ahead, working behind, and staying on track

- Number of students who have completed Determined Knowledge

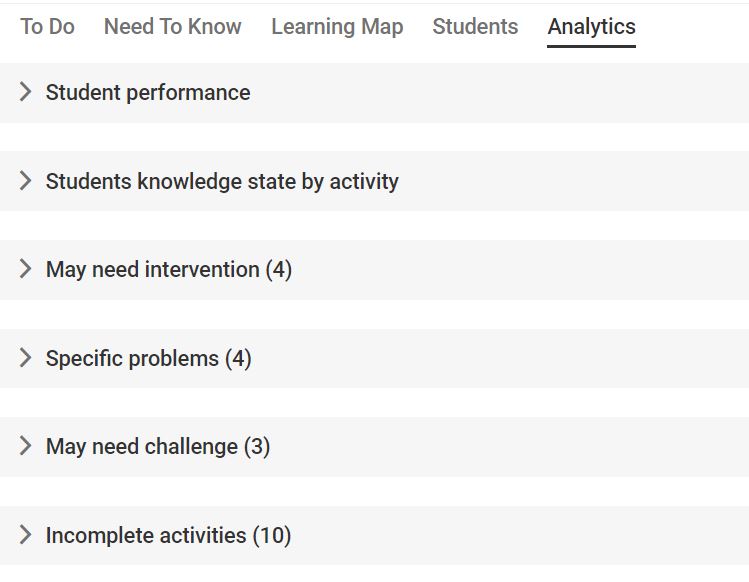

Analytics Tab

The Analytics section of KnowledgePath will share some additional visual representations of the underlying data. When you first enter the Analytics section, it will display a collapsed view. Simply click the arrow > to the left of the heading to expand the view.

After reviewing the content of each section, you can determine the type(s) of interventions needed. For example, you might decided to reach out to those students listed under the “May Need a Challenge” section to acknowledge their accomplishments and encourage them to keep up the great work.

KnowledgePath Grading

KnowledgePath assignments are due on Wednesday to help encourage students to review the content and assess their understanding before applying the content to their weekly discussion and assignments. The adaptive system has been configured to automatically sync with Canvas at midnight following the due date, and then nightly from that time forward. This often causes confusion for the students because they expect the assignment to be cleared from their “To-Do List” once the assignment is completed. You can reassure students that their grades will appear in the grade book once the next sync occurs.

Even though KnowledgePath assignments have a Wednesday due date, the system will not recognize when students are late to participate. Therefore, the late penalty is not applied. We want to encourage students to revisit the content and activities throughout the course. Students should be encouraged to revise their work in KnowledgePath for both a greater understanding of the material and to improve their score.

Unpacking the KnowledgePath Toolbox

Grading

This link will bring you to the grade dashboard. At the top you will find a blue box that will allow you to manually “Submit Grading Information” if you wanted to refresh the grades before the next scheduled sync.

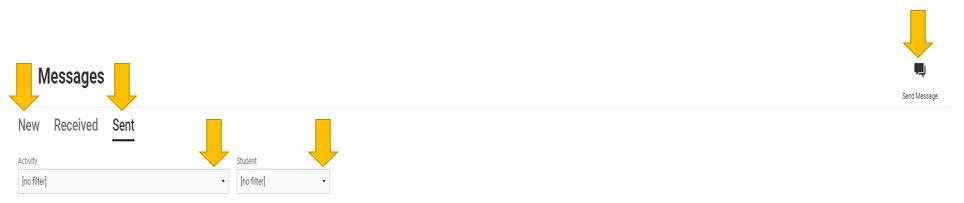

Messages

This link will take you to your inbox. Here you can compose a message, read incoming messages, or review messages sent. When composing a message, you can choose to send an individual message to a student, or you can select multiple students and send a group or class message.

Interactions

This link will allow you to review your interactions with students and assess their effectiveness.

Interventions

This link will allow you to review the interventions you have recorded. Examples of interventions might include providing personal tutoring or direct support, providing additional classroom instruction, or sending a message of encouragement.

Submissions

This tool is not currently used at Bay Path Online.

Collaborative Activities

This tool is not currently used at Bay Path Online.

Pairings

This link allows you to review active pairings and assess their effectiveness.

Bookmarks

This link allows you to see student-created bookmarks. This might provide insightful information in terms of what students are struggling with or what they find most interesting.

Highlights

This link allows you to see student-created highlight. This might provide insightful information in terms of what students are struggling with or what they find most interesting.

Annotations

This link allows you to see student-created annotations. This might provide insightful information in terms of what students are struggling with or what they find most interesting.

Comment Banks

This tool is not currently used at Bay Path Online.

Queried Questions

This link allows you to review the questions that have been queried by students.

Search Content

The Search Content feature in the Toolbox works to find a word or phrase in the learning material. Simply enter a word or phrase into the search box and the system will return the activity(s) in which that term can be found.

Watch Feature

The Watch feature, although not directly a Toolbox item, is located proximally to the toolbox. This feature can provide additional insights, similar to a ticker-tape display, demonstrating the activity of the students throughout the assignment. The work of students is displayed chronologically by date and by the student; meaning one student’s activities on that date will be listed and then it will go to another student and their activities. This is a good window into the actual engagement with the content in KnowledgePath, as it shows how often and what the students are doing at a more granular level than simply listing the time spent.

Interacting with Students

Class Roster

The names of the students in your class can be found on the right side of the Learning Map section. You can click on any student to see their personal Learning Map, and if you hover over their initials, you will gain access to the ellipsis menu … This menu allows you to do the following:

- Send a message

- Encourage the student to practice an assignment

- Record an intervention

KnowledgePath Messaging

You can send a message from the KnowledgePath Toolbox. You will always see this button on any activity that you select. It is worth noting that all communications within the KnowledgePath system are independent of Canvas or Gmail. Therefore, your communication using KnowledgePath should reflect messages directly relating to the information in the platform and not general topics.

Once you open Messages, there are a number of options available to you. You can send a message by clicking on the icon in the top right corner, or you can filter the views of messages to only see New, Received or Sent messages, as shown by the arrows on the left. You can also filter to view messages by specific activities or students.

Interventions

Interventions allow the instructor to record additional efforts made on behalf of the student.

To record an intervention, you would open the Students tab and click the ellipsis menu found by the students initials. This menu will provide you the option to Record Intervention. Once selected, provide a summary of what you did in the large free-form text box provided. When recording an intervention, you can select from one of the three options in a drop down menu:

- None

- Personal Tutoring

- Further Class Instruction

The intervention feature allows the system to track and monitor your engagement with students.

Interactions

Interactions are slightly different than interventions in that they are focused on the communication that takes place between instructor and students as opposed to instructional interventions provided. For example, if you see that a student is struggling, you may choose to select the “Practice Assignment” option provided in the ellipsis menu on your class roster. Once selected, the system triggers a notification to be sent to the student encouraging them to practice. This interaction will be automatically recorded in the Interactions dashboard.

Similarly, you can see the messages sent or received by students.

When looking at the Interactions Dashboard (accessible via the toolbox), the menu will allow you to examine Interactions by type, status, student, assignment, activity, and date range. You can enter the specific student into this section and all Interactions as specified through the drop-down parameters will be displayed, if available.