Nature vs. Nurture

Introduction

This section will focus on the long standing nature vs. nurture debate. Are genes or environment most influential in determining the behavior of individuals and for accounting for differences among people? Most scientists now agree that both genes and environment play crucial roles in most human behaviors, and yet we still have much to learn about how nature (our biological makeup) and nurture (the experiences that we have during our lives) work together (Harris, 1998; Pinker, 2002). For example, psychologists interested in the nature-nurture issue ask whether people’s innate intelligence can buffer them against growing up in poverty—it can, but only a bit (Damian, Su, Shanahan, Trautwein, & Roberts, 2015).

The proportion of the observed differences on characteristics among people (e.g., in terms of their height, intelligence, or optimism) that is due to genetics is known as the heritability of the characteristic, and we will make much use of this term in the sections to come. We will see, for example, that the heritability of intelligence is very high (about .85 out of 1.0) and that the heritability of extraversion is about .50. But we will also see that nature and nurture interact in complex ways, making the question of “Is it nature or is it nurture?” very difficult to answer. This section will explore the influence of both genetics and environment on people.

Benjamin, L. T., Jr., & Baker, D. B. (2004). From seance to science: A history of the profession of psychology in America. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson.

Damian, R. I., Su, R., Shanahan, M., Trautwein, U., & Roberts, B. W. (2015). Can personality traits and intelligence compensate for background disadvantage? Predicting status attainment in adulthood. Journal of personality and social psychology, 109(3), 473.

Harris, J. (1998). The nurture assumption: Why children turn out the way they do. New York, NY: Touchstone Books; Pinker, S. (2002). The blank slate: The modern denial of human nature. New York, NY: Penguin Putnam.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Nature vs. Nurture

Biology or Environment?

There are three related problems at the intersection of philosophy and science that are fundamental to our understanding of our relationship to the natural world: the mind–body problem, the free will problem, and the nature–nurture problem. These great questions have a lot in common. Everyone, even those without much knowledge of science or philosophy, has opinions about the answers to these questions that come simply from observing the world we live in. Our feelings about our relationship with the physical and biological world often seem incomplete. We are in control of our actions in some ways, but at the mercy of our bodies in others; it feels obvious that our consciousness is some kind of creation of our physical brains, at the same time we sense that our awareness must go beyond just the physical. This incomplete knowledge of our relationship with nature leaves us fascinated and a little obsessed, like a cat that climbs into a paper bag and then out again, over and over, mystified every time by a relationship between inner and outer that it can see but can’t quite understand.

It may seem obvious that we are born with certain characteristics while others are acquired, and yet of the three great questions about humans’ relationship with the natural world, only nature–nurture gets referred to as a “debate.” In the history of psychology, no other question has caused so much controversy and offense: We are so concerned with nature–nurture because our very sense of moral character seems to depend on it. While we may admire the athletic skills of a great basketball player, we think of his height as simply a gift, a payoff in the “genetic lottery.” For the same reason, no one blames a short person for his height or someone’s congenital disability on poor decisions: To state the obvious, it’s “not their fault.” But we do praise the concert violinist (and perhaps her parents and teachers as well) for her dedication, just as we condemn cheaters, slackers, and bullies for their bad behavior.

“Paul Altobelli.” Retrieved from https://www.flickr.com/photos/paulaltobelli/7385827296. Licensed under CC BY-2.0.

The problem is, most human characteristics aren’t usually as clear-cut as height or instrument-mastery, affirming our nature–nurture expectations strongly one way or the other. In fact, even the great violinist might have some inborn qualities—perfect pitch, or long, nimble fingers—that support and reward her hard work. And the basketball player might have eaten a diet while growing up that promoted his genetic tendency for being tall. When we think about our own qualities, they seem under our control in some respects, yet beyond our control in others. And often the traits that don’t seem to have an obvious cause are the ones that concern us the most and are far more personally significant. What about how much we drink or worry? What about our honesty, or religiosity, or sexual orientation? They all come from that uncertain zone, neither fixed by nature nor totally under our own control.

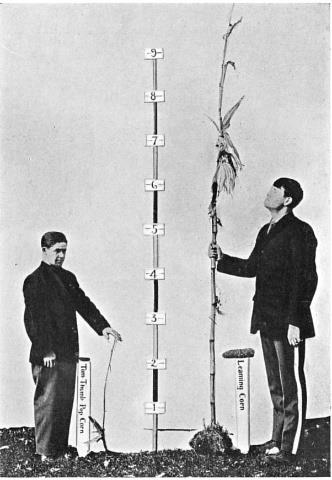

“Critique of the Theory of Evolution.” Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Critique_of_the_Theory_of_Evolution_Fig_076.jpg. Licensed under CC0.

How Do You Study Nature vs. Nurture?

One major problem with answering nature-nurture questions about people is, how do you set up an experiment? In nonhuman animals, there are relatively straightforward experiments for tackling nature–nurture questions. Say, for example, you are interested in aggressiveness in dogs. You want to test for the more important determinant of aggression: being born to aggressive dogs or being raised by them. You could mate two aggressive dogs—angry Chihuahuas—together, and mate two nonaggressive dogs—happy beagles—together, then switch half the puppies from each litter between the different sets of parents to raise. You would then have puppies born to aggressive parents (the Chihuahuas) but being raised by nonaggressive parents (the Beagles), and vice versa, in litters that mirror each other in puppy distribution. The big questions are: Would the Chihuahua parents raise aggressive beagle puppies? Would the beagle parents raise nonaggressive Chihuahua puppies? Would the puppies’ nature win out, regardless of who raised them? Or… would the result be a combination of nature and nurture? Much of the most significant nature–nurture research has been done in this way (Scott & Fuller, 1998), and animal breeders have been doing it successfully for thousands of years. In fact, it is fairly easy to breed animals for behavioral traits.

With people, however, we can’t assign babies to parents at random, or select parents with certain behavioral characteristics to mate, merely in the interest of science (though history does include horrific examples of such practices, in misguided attempts at “eugenics,” the shaping of human characteristics through intentional breeding). In typical human families, children’s biological parents raise them, so it is very difficult to know whether children act like their parents due to genetic (nature) or environmental (nurture) reasons. Nevertheless, despite our restrictions on setting up human-based experiments, we do see real-world examples of nature-nurture at work in the human sphere—though they only provide partial answers to our many questions.

Human Studies

The science of how genes and environments work together to influence behavior is called behavioral genetics. The easiest opportunity we have to observe this is the adoption study. When children are put up for adoption, the parents who give birth to them are no longer the parents who raise them. This setup isn’t quite the same as the experiments with dogs (children aren’t assigned to random adoptive parents in order to suit the particular interests of a scientist) but adoption still tells us some interesting things, or at least confirms some basic expectations. For instance, if the biological child of tall parents were adopted into a family of short people, do you suppose the child’s growth would be affected? What about the biological child of a Spanish-speaking family adopted at birth into an English-speaking family? What language would you expect the child to speak? And what might these outcomes tell you about the difference between height and language in terms of nature-nurture?

Another option for observing nature-nurture in humans involves twin studies. There are two types of twins: monozygotic (MZ) and dizygotic (DZ). Monozygotic twins, also called “identical” twins, result from a single zygote (fertilized egg) and have the same DNA. They are essentially clones. Dizygotic twins, also known as “fraternal” twins, develop from two zygotes and share 50% of their DNA. Fraternal twins are ordinary siblings who happen to have been born at the same time. To analyze nature–nurture using twins, we compare the similarity of MZ and DZ pairs. Sticking with the features of height and spoken language, let’s take a look at how nature and nurture apply: Identical twins, unsurprisingly, are almost perfectly similar for height. The heights of fraternal twins, however, are like any other sibling pairs: more similar to each other than to people from other families, but hardly identical. This contrast between twin types gives us a clue about the role genetics plays in determining height. Now consider spoken language. If one identical twin speaks Spanish at home, the co-twin with whom she is raised almost certainly does too. But the same would be true for a pair of fraternal twins raised together. In terms of spoken language, fraternal twins are just as similar as identical twins, so it appears that the genetic match of identical twins doesn’t make much difference.

Retrieved from https://pixabay.com/en/baby-twins-brother-and-sister-772439/. Licensed under CC0.

Turkheimer, E. (2018). The nature-nurture question. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://nobaproject.com/modules/the-nature-nurture-question. Licensed under CC-BY-SA-4.0.

What Have We Learned About Nature-Nurture?

It would be satisfying to be able to say that nature–nurture studies have given us conclusive and complete evidence about where traits come from, with some traits clearly resulting from genetics and others almost entirely from environmental factors, such as childrearing practices and personal will; but that is not the case. Instead, everything has turned out to have some footing in genetics. The more genetically-related people are, the more similar they are—for everything: height, weight, intelligence, personality, mental illness, etc. Sure, it seems like common sense that some traits have a genetic bias. For example, adopted children resemble their biological parents even if they have never met them, and identical twins are more similar to each other than are fraternal twins. And while certain psychological traits, such as personality or mental illness (e.g., schizophrenia), seem reasonably influenced by genetics, it turns out that the same is true for political attitudes, how much television people watch (Plomin, Corley, DeFries, & Fulker, 1990), and whether or not they get divorced (McGue & Lykken, 1992).

It may seem surprising, but genetic influence on behavior is a relatively recent discovery. In the middle of the 20th century, psychology was dominated by the doctrine of behaviorism, which held that behavior could only be explained in terms of environmental factors. Psychiatry concentrated on psychoanalysis, which probed for roots of behavior in individuals’ early life-histories. The truth is, neither behaviorism nor psychoanalysis is incompatible with genetic influences on behavior, and neither Freud nor Skinner was naive about the importance of organic processes in behavior. Nevertheless, in their day it was widely thought that children’s personalities were shaped entirely by imitating their parents’ behavior, and that schizophrenia was caused by certain kinds of “pathological mothering.” Whatever the outcome of our broader discussion of nature–nurture, the basic fact that the best predictors of an adopted child’s personality or mental health are found in the biological parents he or she has never met, rather than in the adoptive parents who raised him or her, presents a significant challenge to purely environmental explanations of personality or psychopathology. The message is clear: You can’t leave genes out of the equation. But keep in mind, no behavioral traits are completely inherited, so you can’t leave the environment out altogether, either.

Trying to untangle the various ways nature-nurture influences human behavior can be messy, and often common-sense notions can get in the way of good science. One very significant contribution of behavioral genetics that has changed psychology for good can be very helpful to keep in mind: When your subjects are biologically-related, no matter how clearly a situation may seem to point to environmental influence, it is never safe to interpret a behavior as wholly the result of nurture without further evidence. For example, when presented with data showing that children whose mothers read to them often are likely to have better reading scores in third grade, it is tempting to conclude that reading to your kids out loud is important to success in school; this may well be true, but the study as described is inconclusive, because there are genetic as well as environmental pathways between the parenting practices of mothers and the abilities of their children. This is a case where “correlation does not imply causation,” as they say. To establish that reading aloud causes success, a scientist can either study the problem in adoptive families (in which the genetic pathway is absent) or by finding a way to randomly assign children to oral reading conditions.

The difficulties with finding clear-cut solutions to nature–nurture problems bring us back to the other great questions about our relationship with the natural world: the mind-body problem and free will. Investigations into what we mean when we say we are aware of something reveal that consciousness is not simply the product of a particular area of the brain, nor does choice turn out to be an orderly activity that we can apply to some behaviors but not others. So it is with nature and nurture: What at first may seem to be a straightforward matter, able to be indexed with a single number, becomes more and more complicated the closer we look. The many questions we can ask about the intersection among genes, environments, and human traits—how sensitive are traits to environmental change, and how common are those influential environments; are parents or culture more relevant; how sensitive are traits to differences in genes, and how much do the relevant genes vary in a particular population; does the trait involve a single gene or a great many genes; is the trait more easily described in genetic or more-complex behavioral terms?—may have different answers, and the answer to one tells us little about the answers to the others.

It is tempting to predict that the more we understand the wide-ranging effects of genetic differences on all human characteristics—especially behavioral ones—our cultural, ethical, legal, and personal ways of thinking about ourselves will have to undergo profound changes in response. Perhaps criminal proceedings will consider genetic background. Parents, presented with the genetic sequence of their children, will be faced with difficult decisions about reproduction. These hopes or fears are often exaggerated. In some ways, our thinking may need to change—for example, when we consider the meaning behind the fundamental American principle that all men are created equal. Human beings differ, and like all evolved organisms they differ genetically. The Declaration of Independence predates Darwin and Mendel, but it is hard to imagine that Jefferson—whose genius encompassed botany as well as moral philosophy—would have been alarmed to learn about the genetic diversity of organisms. One of the most important things modern genetics has taught us is that almost all human behavior is too complex to be nailed down, even from the most complete genetic information, unless we’re looking at identical twins. The science of nature and nurture has demonstrated that genetic differences among people are vital to human moral equality, freedom, and self-determination, not opposed to them. As Mordecai Kaplan said about the role of the past in Jewish theology, genetics gets a vote, not a veto, in the determination of human behavior. We should indulge our fascination with nature–nurture while resisting the temptation to oversimplify it.

Turkheimer, E. (2018). The nature-nurture question. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://nobaproject.com/modules/the-nature-nurture-question. Licensed under CC-BY-SA-4.0.

Nature vs. Nurture-Video

Abraham Feinberg. (2016, July 31). Nature vs. Nurture Part I. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0mKvYic-4Do. Standard YouTube License.

Summary

People have a deep intuition about what has been called the “nature–nurture question.” Some aspects of our behavior feel as though they originate in our genetic makeup, while others feel like the result of our upbringing or our own hard work. The scientific field of behavior genetics attempts to study these differences empirically, either by examining similarities among family members with different degrees of genetic relatedness, or, more recently, by studying differences in the DNA of people with different behavioral traits. The scientific methods that have been developed are ingenious, but often inconclusive. Many of the difficulties encountered in the empirical science of behavior genetics turn out to be conceptual, and our intuitions about nature and nurture get more complicated the harder we think about them. In the end, it is an oversimplification to ask how “genetic” some particular behavior is. Genes and environments always combine to produce behavior, and the real science is in the discovery of how they combine for a given behavior.

Turkheimer, E. (2018). The nature-nurture question. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://nobaproject.com/modules/the-nature-nurture-question. Licensed under CC-BY-SA-4.0.