Accuracy and Inaccuracy of Memory

Introduction

We have learned about memory in terms of stages and processes, as well as explicit and implicit memory and there major memory stages: sensory, short-term, and long-term. As we have seen, our memories are not perfect. They fail, in part, due to our inadequate encoding and storage, as well as due to our inability to accurately retrieve stored information. But memory is also influenced by the setting in which it occurs, by the events that occur to us after we have experienced an event, and by the cognitive processes that we use to help us remember. Although our cognition allows us to attend to, rehearse, and organize information, cognition may also lead to distortions and errors in our judgments and our behaviors.

In this section we consider some of the cognitive biases that are known to influence humans. Cognitive biases are errors in memory or judgment that are caused by the inappropriate use of cognitive processes. The study of cognitive biases is important both because it relates to the important psychological theme of accuracy versus inaccuracy in perception and because being aware of the types of errors that we may make can help us avoid them and therefore improve our decision-making skills.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Accuracy and Inaccuracy in Memory and Cognition

Psychologists often use behavioral responses (such as memory tests and reaction times) to draw inferences about what and how people remember. We will see that although we have very good memory for some things, our memories are far from perfect (Schacter, 1996). The errors that we make are due to the fact that our memories are not simply recording devices that input, store, and retrieve the world around us. Rather, we actively process and interpret information as we remember and recollect it, and these cognitive processes influence what we remember and how we remember it. Because memories are constructed, not recorded, when we remember events we don’t reproduce exact replicas of those events (Bartlett, 1932). People who read the words “dream, sheets, rest, snore, blanket, tired, and bed” and then are asked to remember the words often think that they saw the word sleep even though that word was not in the list (Roediger & McDermott, 1995). Although much research in the area of memory and cognition is basic in orientation, the work has profound influence on our everyday experiences. Our cognitive processes influence the accuracy and inaccuracy of our memories and our judgments, and they lead us to be vulnerable to the types of errors that eyewitnesses, such as Jennifer Thompson, may make. Understanding these potential errors is the first step in learning to avoid them.

In 1984 Jennifer Thompson was a 22-year-old college student in North Carolina. One night a man broke into her apartment, put a knife to her throat, and raped her. According to her own account, Ms. Thompson studied her rapist throughout the incident with great determination to memorize his face. She said: “I studied every single detail on the rapist’s face. I looked at his hairline; I looked for scars, for tattoos, for anything that would help me identify him. When and if I survived.” Ms. Thompson went to the police that same day to create a sketch of her attacker, relying on what she believed was her detailed memory. Several days later, the police constructed a photographic lineup. Thompson identified Ronald Cotton as the rapist, and she later testified against him at trial. She was positive it was him, with no doubt in her mind.

“I was sure. I knew it. I had picked the right guy, and he was going to go to jail. If there was the possibility of a death sentence, I wanted him to die. I wanted to flip the switch.” As positive as she was, it turned out that Jennifer Thompson was wrong. But it was not until after Mr. Cotton had served 11 years in prison for a crime he did not commit that conclusive DNA evidence indicated that Bobby Poole was the actual rapist, and Cotton was released from jail. Jennifer Thompson’s memory had failed her, resulting in a substantial injustice. It took definitive DNA testing to shake her confidence, but she now knows that despite her confidence in her identification, it was wrong. Consumed by guilt, Thompson sought out Cotton when he was released from prison, and they have since become friends (Innocence Project, n.d.; Thompson, 2000)

Retrieved from https://www.flickr.com/photos/poptech/5105594032. Licensed under CC BY-SA-2.0.

Innocence Project. (n.d.). Ronald Cotton. Retrieved from http://www.innocenceproject.org/Content/72.php; Thompson, J. (2000, June 18). I was certain, but I was wrong. New York Times. Retrieved from http://faculty.washington.edu/gloftus/Other_

Roediger, H. L., & McDermott, K. B. (1995). Creating false memories: Remembering words not presented in lists. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 21(4), 803–814.

Schacter, D. L. (1996). Searching for memory: The brain, the mind, and the past (1st ed.). New York, NY: Basic Books.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Types of Cognitive Biases

One potential error in memory involves mistakes in differentiating the sources of information. Source monitoring refers to the ability to accurately identify the source of a memory. Perhaps you’ve had the experience of wondering whether you really experienced an event or only dreamed or imagined it. If so, you wouldn’t be alone. Rassin, Merkelbach, and Spaan (2001) reported that up to 25% of college students reported being confused about real versus dreamed events. Studies suggest that people who are fantasy-prone are more likely to experience source monitoring errors (Winograd, Peluso, & Glover, 1998), and such errors also occur more often for both children and the elderly than for adolescents and younger adults (Jacoby & Rhodes, 2006).

In other cases, we may be sure that we remembered the information from real life but be uncertain about exactly where we heard it. Imagine that you read a news story in a tabloid magazine such as the National Enquirer. You probably would have discounted the information because you know that its source is unreliable. But what if later you were to remember the story but forget the source of the information? If this happens, you might become convinced that the news story is true because you forget to discount it. The sleeper effect refers to the attitude change that occurs over time when we forget the source of information (Pratkanis, Greenwald, Leippe, & Baumgardner, 1988).

Still, in other cases, we may forget where we learned information and mistakenly assume that we created the memory ourselves. Kaavya Viswanathan, the author of the book How Opal Mehta Got Kissed, Got Wild, and Got a Life, was accused of plagiarism when it was revealed that many parts of her book were very similar to passages from other material. Viswanathan argued that she had simply forgotten that she had read the other works, mistakenly assuming she had made up the material herself. And the musician George Harrison claimed that he was unaware that the melody of his song “My Sweet Lord” was almost identical to an earlier song by another composer. The judge in the copyright suit that followed ruled that Harrison didn’t intentionally commit the plagiarism. (Please use this knowledge to become extra vigilant about source attributions in your written work, not to try to excuse yourself if you are accused of plagiarism.)

Schematic Processing: Distortions Based on Expectations

We have seen that schemas help us remember information by organizing material into coherent representations. However, although schemas can improve our memories, they may also lead to cognitive biases. Using schemas may lead us to falsely remember things that never happened to us and to distort or misremember things that did. For one, schemas lead to the confirmation bias, which is the tendency to verify and confirm our existing memories rather than to challenge and disconfirm them. The confirmation bias occurs because once we have schemas, they influence how we seek out and interpret new information. The confirmation bias leads us to remember information that fits our schemas better than we remember information that disconfirms them (Stangor & McMillan, 1992), a process that makes our stereotypes very difficult to change. We often ask questions in ways that confirm our schemas (Trope & Thompson, 1997). If we think that a person is an extrovert, we might ask her about ways that she likes to have fun, thereby making it more likely that we will confirm our beliefs. In short, once we begin to believe in something—for instance, a stereotype about a group of people—it becomes very difficult to later convince us that these beliefs are not true; the beliefs become self-confirming.

Darley and Gross (1983) demonstrated how schemas about social class could influence memory. In their research they gave participants a picture and some information about a fourth-grade girl named Hannah. To activate a schema about her social class, Hannah was pictured sitting in front of a nice suburban house for one-half of the participants and pictured in front of an impoverished house in an urban area for the other half. Then the participants watched a video that showed Hannah taking an intelligence test. As the test went on, Hannah got some of the questions right and some of them wrong, but the number of correct and incorrect answers were the same in both conditions. Then the participants were asked to remember how many questions Hannah got right and wrong. Demonstrating that stereotypes had influenced memory, the participants who thought that Hannah had come from an upper-class background remembered that she had gotten more correct answers than those who thought she was from a lower-class background.

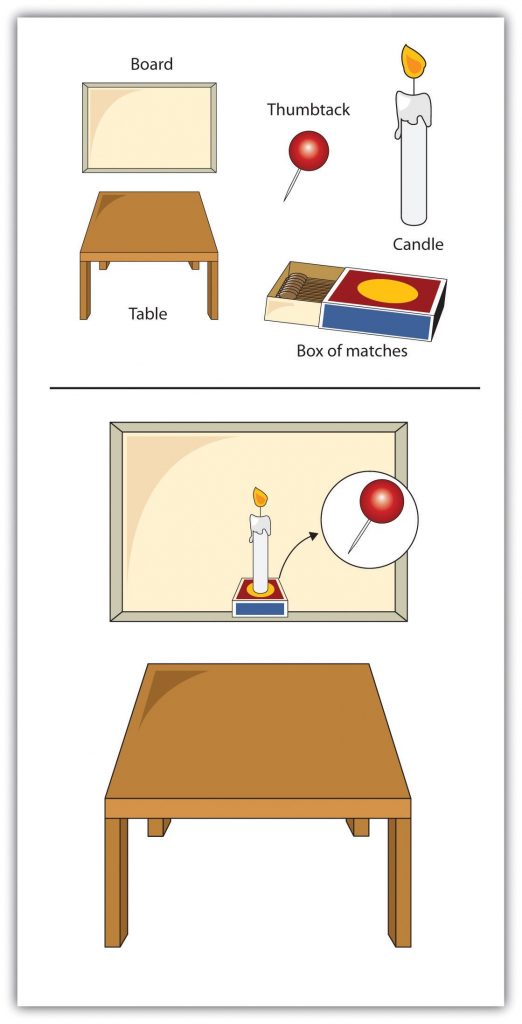

Functional fixedness occurs when people’s schemas prevent them from using an object in new and nontraditional ways. Duncker (1945) gave participants a candle, a box of thumbtacks, and a book of matches, and asked them to attach the candle to the wall so that it did not drip onto the table below. Few of the participants realized that the box could be tacked to the wall and used as a platform to hold the candle. The problem again is that our existing memories are powerful and they bias the way we think about new information. Because the participants were “fixated” on the box’s normal function of holding thumbtacks, they could not see its alternative use.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Darley, J. M., & Gross, P. H. (1983). A hypothesis-confirming bias in labeling effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44, 20–33.

Duncker, K. (1945). On problem-solving. Psychological Monographs, 58, 5.

Jacoby, L. L., & Rhodes, M. G. (2006). False remembering in the aged. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15(2), 49–53.

Pratkanis, A. R., Greenwald, A. G., Leippe, M. R., & Baumgardner, M. H. (1988). In search of reliable persuasion effects: III. The sleeper effect is dead: Long live the sleeper effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(2), 203–218.

Rassin, E., Merckelbach, H., & Spaan, V. (2001). When dreams become a royal road to confusion: Realistic dreams, dissociation, and fantasy proneness. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 189(7), 478–481.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Stangor, C., & McMillan, D. (1992). Memory for expectancy-congruent and expectancy-incongruent information: A review of the social and social developmental literatures. Psychological Bulletin, 111(1), 42–61.

Trope, Y., & Thompson, E. (1997). Looking for truth in all the wrong places? Asymmetric search of individuating information about stereotyped group members. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 229–241.

Wason, P. (1960). On the failure to eliminate hypotheses in a conceptual task. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 12(3), 129–140.

Winograd, E., Peluso, J. P., & Glover, T. A. (1998). Individual differences in susceptibility to memory illusions. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 12(Spec. Issue), S5–S27.

Misinformation Effects: How Information That Comes Later Can Distort Memory

A particular problem for eyewitnesses, such as Jennifer Thompson, is that our memories are often influenced by the things that occur to us after we have learned the information (Erdmann, Volbert, & Böhm, 2004; Loftus, 1979; Zaragoza, Belli, & Payment, 2007). This new information can distort our original memories, such that we are no longer sure what the real information is and what was provided later. The misinformation effect refers to errors in memory that occur when new information influences existing memories.

In an experiment by Loftus and Palmer (1974), participants viewed a film of a traffic accident and then, according to random assignment to experimental conditions, answered one of three questions:

1. “About how fast were the cars going when they hit each other?”

2. “About how fast were the cars going when they smashed each other?”

3. “About how fast were the cars going when they contacted each other?”

Although all the participants saw the same accident, their estimates of the cars’ speed varied by condition. Participants who had been asked about the cars “smashing” each other estimated the highest average speed, and those who had been asked the “contacted” question estimated the lowest average speed.

| Verb Used in Question | Estimated Miles Per Hour |

| Smashed | 40.8 mph |

| Hit | 34 mph |

| Contacted | 30.8 mph |

The ease with which memories can be created or implanted is particularly problematic when the events to be recalled have important consequences. Therapists often argue that patients may repress memories of traumatic events they experienced as children, such as childhood sexual abuse, and then recover the events years later as the therapist leads them to recall the information—for instance, by using dream interpretation and hypnosis (Brown, Scheflin, & Hammond, 1998).

But other researchers argue that painful memories, such as sexual abuse, are usually very well remembered, that few memories are actually repressed, and that even if they are it is virtually impossible for patients to accurately retrieve them years later (McNally, Bryant, & Ehlers, 2003; Pope, Poliakoff, Parker, Boynes, & Hudson, 2007). These researchers have argued that the procedures used by the therapists to “retrieve” the memories are more likely to actually implant false memories, leading the patients to erroneously recall events that did not actually occur. Because hundreds of people have been accused, and even imprisoned, on the basis of claims about “recovered memory” of child sexual abuse, the accuracy of these memories has important societal implications. Many psychologists now believe that most of these claims of recovered memories are due to implanted, rather than real, memories (Loftus & Ketcham, 1994).

Ceci, S. J., Huffman, M. L. C., Smith, E., & Loftus, E. F. (1994). Repeatedly thinking about a non-event: Source misattributions among preschoolers. Consciousness and Cognition: An International Journal, 3(3–4), 388–407.

Belli, R. F., & Payment, K. E. (2007). Misinformation effects and the suggestibility of eyewitness memory. In M. Garry & H. Hayne (Eds.), Do justice and let the sky fall: Elizabeth Loftus and her contributions to science, law, and academic freedom (pp. 35–63). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Brown, D., Scheflin, A. W., & Hammond, D. C. (1998). Memory, trauma treatment, and the law. New York, NY: Norton.

Erdmann, K., Volbert, R., & Böhm, C. (2004). Children report suggested events even when interviewed in a non-suggestive manner: What are its implications for credibility assessment? Applied Cognitive Psychology, 18(5), 589–611; Loftus, E. F. (1979). The malleability of human memory. American Scientist, 67(3), 312–320; Zaragoza, M. S.,

Loftus, E. F., & Ketcham, K. (1994). The myth of repressed memory: False memories and allegations of sexual abuse (1st ed.). New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press.

Loftus, E. F., & Palmer, J. C. (1974). Reconstruction of automobile destruction: An example of the interaction between language and memory. Journal of Verbal Learning & Verbal Behavior, 13(5), 585–589.

Loftus, E. F., & Pickrell, J. E. (1995). The formation of false memories. Psychiatric Annals, 25(12), 720–725.

Mazzoni, G. A. L., Loftus, E. F., & Kirsch, I. (2001). Changing beliefs about implausible autobiographical events: A little plausibility goes a long way. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 7(1), 51–59.

McNally, R. J., Bryant, R. A., & Ehlers, A. (2003). Does early psychological intervention promote recovery from posttraumatic stress? Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 4(2), 45–79; Pope, H. G., Jr., Poliakoff, M. B., Parker, M. P., Boynes, M., & Hudson, J. I. (2007). Is dissociative amnesia a culture-bound syndrome? Findings from a survey of historical literature. Psychological Medicine: A Journal of Research in Psychiatry and the Allied Sciences, 37(2), 225–233.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Overconfidence

One of the most remarkable aspects of Jennifer Thompson’s mistaken identity of Ronald Cotton was her certainty. But research reveals a pervasive cognitive bias toward overconfidence, which is the tendency for people to be too certain about their ability to accurately remember events and to make judgments. David Dunning and his colleagues (Dunning, Griffin, Milojkovic, & Ross, 1990) asked college students to predict how another student would react in various situations. Some participants made predictions about a fellow student whom they had just met and interviewed, and others made predictions about their roommates whom they knew very well. In both cases, participants reported their confidence in each prediction, and accuracy was determined by the responses of the people themselves. The results were clear: Regardless of whether they judged a stranger or a roommate, the participants consistently overestimated the accuracy of their own predictions.

I am sure that you have a clear memory of when you first heard about the 9/11 attacks in 2001, and perhaps also when you heard that Princess Diana was killed in 1997 or when the verdict of the O. J. Simpson trial was announced in 1995. This type of memory, which we experience along with a great deal of emotion, is known as a flashbulb memory—a vivid and emotional memory of an unusual event that people believe they remember very well (Brown & Kulik, 1977).

Heuristic Processing: Availability and Representativeness

Another way that our information processing may be biased occurs when we use heuristics, which are information-processing strategies that are useful in many cases but may lead to errors when misapplied. Let’s consider two of the most frequently applied (and misapplied) heuristics: the representativeness heuristic and the availability heuristic. In many cases, we base our judgments on information that seems to represent, or match, what we expect will happen, while ignoring other potentially more relevant statistical information. When we do so, we are using the representativeness heuristic. Consider, for instance, a group of people who see a flipped coin come up “heads” five times in a row. This group will frequently predict, and perhaps even wager money, that “tails” will be next. This behavior is known as the gambler’s fallacy. But mathematically, the gambler’s fallacy is an error: The likelihood of any single coin flip being “tails” is always 50%, regardless of how many times it has come up “heads” in the past.

Our judgments can also be influenced by how easy it is to retrieve a memory. The tendency to make judgments of the frequency or likelihood that an event occurs on the basis of the ease with which it can be retrieved from memory is known as the availability heuristic (MacLeod & Campbell, 1992; Tversky & Kahneman, 1973). Imagine, for instance, that I asked you to indicate whether there are more words in the English language that begin with the letter “R” or that have the letter “R” as the third letter. You would probably answer this question by trying to think of words that have each of the characteristics, thinking of all the words you know that begin with “R” and all that have “R” in the third position. Because it is much easier to retrieve words by their first letter than by their third, we may incorrectly guess that there are more words that begin with “R,” even though there are, in fact, more words that have “R” as the third letter.

Salience and Cognitive Accessibility

Still another potential for bias in memory occurs because we are more likely to attend to, and thus make use of and remember, some information more than other information. For one, we tend to attend to and remember things that are highly salient, meaning that they attract our attention. Things that are unique, colorful, bright, moving, and unexpected are more salient (McArthur & Post, 1977; Taylor & Fiske, 1978). In one relevant study, Loftus, Loftus, and Messo (1987) showed people images of a customer walking up to a bank teller and pulling out either a pistol or a checkbook. By tracking eye movements, the researchers determined that people were more likely to look at the gun than at the checkbook, and that this reduced their ability to accurately identify the criminal in a lineup that was given later. The salience of the gun drew people’s attention away from the face of the criminal.

People also vary in the schemas that they find important to use when judging others and when thinking about themselves. Cognitive accessibility refers to the extent to which knowledge is activated in memory, and thus likely to be used in cognition and behavior. For instance, you probably know a person who is a golf nut (or fanatic of another sport). All he can talk about is golf. For him, we would say that golf is a highly accessible construct. Because he loves golf, it is important to his self-concept, he sets many of his goals in terms of the sport, and he tends to think about things and people in terms of it. (“If he plays golf, he must be a good person!”) Other people have highly accessible schemas about environmental issues, eating healthy food, or drinking really good coffee. When schemas are highly accessible, we are likely to use them to make judgments of ourselves and others, and this overuse may inappropriately color our judgments.

Counterfactual Thinking

In addition to influencing our judgments about ourselves and others, the ease with which we can retrieve potential experiences from memory can have an important effect on our own emotions. If we can easily imagine an outcome that is better than what actually happened, then we may experience sadness and disappointment. On the other hand, if we can easily imagine that a result might have been worse than what actually happened, we may be more likely to experience happiness and satisfaction. The tendency to think about and experience events according to “what might have been” is known as counterfactual thinking (Kahneman & Miller, 1986; Roese, 2005). Imagine, for instance, that you were participating in an important contest, and you won the silver (second-place) medal. How would you feel? Certainly you would be happy that you won the silver medal, but wouldn’t you also be thinking about what might have happened if you had been just a little bit better—you might have won the gold medal! On the other hand, how might you feel if you won the bronze (third-place) medal? If you were thinking about the counterfactuals (the “what might have beens”) perhaps the idea of not getting any medal at all would have been highly accessible; you’d be happy that you got the medal that you did get, rather than coming in fourth.

Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2010_Winter_Olympic_Men%27s_Snowboard_Cross_medalists.jpg. Licensed under CC BY-SA-2.0.

Perhaps you are thinking that the kinds of errors that we have been talking about don’t seem that important. After all, who really cares if we think there are more words that begin with the letter “R” than there actually are, or if bronze medal winners are happier than the silver medalists? These aren’t big problems in the overall scheme of things. But it turns out that what seems to be relatively small cognitive biases on the surface can have profound consequences for people.

Brown, R., & Kulik, J. (1977). Flashbulb memories. Cognition, 5, 73–98.

Dunning, D., Griffin, D. W., Milojkovic, J. D., & Ross, L. (1990). The overconfidence effect in social prediction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(4), 568–581.

Kahneman, D., & Miller, D. T. (1986). Norm theory: Comparing reality to its alternatives. Psychological Review, 93, 136–153; Roese, N. (2005). If only: How to turn regret into opportunity. New York, NY: Broadway Books.

Loftus, E. F., Loftus, G. R., & Messo, J. (1987). Some facts about “weapon focus.” Law and Human Behavior, 11(1), 55–62.

MacLeod, C., & Campbell, L. (1992). Memory accessibility and probability judgments: An experimental evaluation of the availability heuristic. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(6), 890–902; Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1973). Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability. Cognitive Psychology, 5, 207–232.

McArthur, L. Z., & Post, D. L. (1977). Figural emphasis and person perception. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 13(6), 520–535; Taylor, S. E., & Fiske, S. T. (1978). Salience, attention and attribution: Top of the head phenomena. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 11, 249–288.

Medvec, V. H., Madey, S. F., & Gilovich, T. (1995). When less is more: Counterfactual thinking and satisfaction among Olympic medalists. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 69(4), 603–610.

Schmolck, H., Buffalo, E. A., & Squire, L. R. (2000). Memory distortions develop over time: Recollections of the O. J. Simpson trial verdict after 15 and 32 months. Psychological Science, 11(1), 39–45.

Slovic, P. (Ed.). (2000). The perception of risk. London, England: Earthscan Publications.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Talarico, J. M., & Rubin, D. C. (2003). Confidence, not consistency, characterizes flashbulb memories. Psychological Science, 14(5), 455–461.

Wells, G. L., & Olson, E. A. (2003). Eyewitness testimony. Annual Review of Psychology, 277–295.

Accuracy and Inaccuracy in Memory and Cognition

Crashcourse (2014, May 14). Remembering and Forgetting –Crash Course Psychology #14 [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HVWbrNls-Kw. Standard YouTube License.

Accuracy and Inaccuracy in Memory and Cognition

Our memories fail, in part, due to inadequate encoding and storage, and in part due to the inability to accurately retrieve stored information. The human brain is wired to develop and make use of social categories and schemas. Schemas help us to remember new information but may also lead us to falsely remember things that never happened to us and to distort or misremember things that did. A variety of cognitive biases influence the accuracy of our judgments. Memories that are stored in long-term memory (LTM) are not isolated, but rather are linked together into categories and schemas. Schemas are important in part because they help us encode and retrieve information by providing an organizational structure for it.

Cognitive biases are errors in memory or judgment that are caused by the inappropriate use of cognitive processes. These biases are caused by the overuse of schemas, the reliance on salient and cognitive accessible information, and the use of rule-of-thumb strategies known as heuristics. These biases include errors in source monitoring, the confirmation bias, functional fixedness, the misinformation effect, overconfidence, and counterfactual thinking. Understanding the potential cognitive errors we frequently make can help us make better decisions and engage in more appropriate behaviors.

Although cognitive biases are common, they are not impossible to control. One possible solution is to provide people with better feedback about their judgments. Weather forecasters, for instance, learn to be quite accurate in their judgments because they have clear feedback about the accuracy of their predictions. Other research has found that accessibility biases can be reduced by leading people to consider multiple alternatives rather than focus only on the most obvious ones; particularly by leading people to think about opposite possible outcomes than the ones they are expecting (Lilienfeld, Ammirtai, & Landfield, 2009). Forensic psychologists are also working to reduce the number of incidences of false identification by helping police develop better procedures for interviewing both suspects and eyewitnesses (Steblay, Dysart, Fulero, & Lindsay, 2001).

Lilienfeld, S. O., Ammirati, R., & Landfield, K. (2009). Giving debiasing away: Can psychological research on correcting cognitive errors promote human welfare? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4(4), 390–398. Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.