Social Psychology

Introduction

In this section we will cover the topic of social psychology, which is defined as the scientific study of how we feel about, think about, and behave toward the other people around us, and how those people influence our thoughts, feelings, and behavior. A fundamental principle of social psychology is that although we may not always be aware of it, our cognitions, emotions, and behaviors are substantially influenced by the people with whom we are interacting. Essentially, people will change their behavior to align with the social situation at hand. If we are in a new situation or are unsure how to behave, we will take our cues from other individuals.

The field of social psychology studies topics at both the intra- and interpersonal levels. Intrapersonal topics (those that pertain to the individual) include emotions and attitudes, the self, and social cognition (the ways in which we think about ourselves and others). Interpersonal topics (those that pertain to dyads and groups) include helping behavior, aggression, prejudice and discrimination, attraction and close relationships, and group processes and intergroup relationships. In this section, we will focus on the intrapersonal topics of social psychology, including social roles, social norms, and scripts.

OpenStax, Self-presentation. OpenStax CNX. Dec 16, 2014 http://cnx.org/contents/a3e2787e-10c1-4e97-be22-0bd93b609b70@5. Retrieved from https://cnx.org/contents/Sr8Ev5Og@5.52:o-J4fhDB@5/Self-presentation. Licensed under CC BY-4.0.

Social Psychology

Social psychology is the branch of psychological science mainly concerned with understanding how the presence of others affects our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Just as clinical psychology focuses on mental disorders and their treatment, and developmental psychology investigates the way people change across their lifespan, social psychology has its own focus. As the name suggests, this science is all about investigating the ways groups function, the costs and benefits of social status, the influences of culture, and all the other psychological processes involving two or more people.

Social psychology is such an exciting science precisely because it tackles issues that are so familiar and so relevant to our everyday life. Humans are “social animals.” Like bees and deer, we live together in groups. Unlike those animals, however; people are unique in that we care a great deal about our relationships. In fact, a classic study of life stress found that the most stressful events in a person’s life—the death of a spouse, divorce, and going to jail—are so painful because they entail the loss of relationships (Holmes & Rahe, 1967). We spend a huge amount of time thinking about and interacting with other people, and researchers are interested in understanding these thoughts and actions. Giving up a seat on the bus for another person is an example of social psychology. So is disliking a person because he is wearing a shirt with the logo of a rival sports team. Flirting, conforming, arguing, trusting, competing—these are all examples of topics that interest social psychology researchers.

Retrieved from https://www.flickr.com/photos/needoptic/4620692958. Licensed under CC BY-ND-2.0.

At times, science can seem abstract and far removed from the concerns of daily life. When neuroscientists discuss the workings of the anterior cingulate cortex, for example, it might sound important. But the specific parts of the brain and their functions do not always seem directly connected to the stuff you care about: parking tickets, holding hands, or getting a job. Social psychology feels so close to home because it often deals with universal psychological processes to which people can easily relate. For example, people have a powerful need to belong (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). It doesn’t matter if a person is from Israel, Mexico, or the Philippines; we all have a strong need to make friends, start families, and spend time together. We fulfill this need by doing things such as joining teams and clubs, wearing clothing that represents “our group,” and identifying ourselves based on national or religious affiliation. It feels good to belong to a group. Research supports this idea. In a study of the most and least happy people, the differentiating factor was not gender, income, or religion; it was having high-quality relationships (Diener & Seligman, 2002). Even introverts report being happier when they are in social situations (Pavot, Diener & Fujita, 1990). Further evidence can be found by looking at the negative psychological experiences of people who do not feel they belong. People who feel lonely or isolated are more vulnerable to depression and problems with physical health (Cacioppo, & Patrick, 2008)

Social Psychology as a Science

The need to belong is also a useful example of the ways the various aspects of psychology fit together. Psychology is a science that can be sub-divided into specialties such as “abnormal psychology” (the study of mental illness) or “developmental psychology” (the study of how people develop across the life span). In daily life, however, we don’t stop and examine our thoughts or behaviors as being distinctly social versus developmental versus personality-based versus clinical. In daily life, these all blend together. For example, the need to belong is rooted in developmental psychology. Developmental psychologists have long paid attention to the importance of attaching to a caregiver, feeling safe and supported during childhood, and the tendency to conform to peer pressure during adolescence. Similarly, clinical psychologists—those who research mental disorders– have pointed to people feeling a lack of belonging to help explain loneliness, depression, and other psychological pains. In practice, psychologists separate concepts into categories such as “clinical,” “developmental,” and “social” only out of scientific necessity. It is easier to simplify thoughts, feelings, and behaviors in order to study them. Each psychological sub-discipline has its own unique approaches to research. You may have noticed that this is almost always how psychology is taught, as well. You take a course in personality, another in human sexuality, and a third in gender studies, as if these topics are unrelated. In day-to-day life, however; these distinctions do not actually exist, and there is heavy overlap between the various areas of psychology.

Retrieved from https://www.flickr.com/photos/barnigomez/23490179751. Licensed under CC BY-2.0.

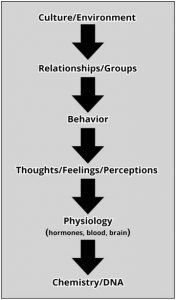

In psychology, there are varying levels of analysis. Take the example of a toddler watching her mother make a phone call: the toddler is curious, and is using observational learning to teach herself about this machine called a telephone. At the most specific levels of analysis, we might understand that various neurochemical processes are occurring in the toddler’s brain. We might be able to use imaging techniques to see that the cerebellum, among other parts of the brain, is activated with electrical energy. If we could “pull back” our scientific lens, we might also be able to gain insight into the toddler’s own experience of the phone call. She might be confused, interested, or jealous. Moving up to the next level of analysis, we might notice a change in the toddler’s behavior: during the call she furrows her brow, squints her eyes, and stares at her mother and the phone. She might even reach out and grab at the phone. At still another level of analysis, we could see the ways that her relationships enter into the equation. We might observe, for instance, that the toddler frowns and grabs at the phone when her mother uses it, but plays happily and ignores it when her stepbrother makes a call. All of these chemical, emotional, behavioral, and social processes occur simultaneously. None of them is the objective truth. Instead, each offers clues into better understanding what, psychologically speaking, is happening.

Biswas-Diener, R. (2018). An introduction to the science of social psychology. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. DOI:nobaproject.com. Retrieved from http://nobaproject.com/modules/an-introduction-to-the-science-of-social-psychology. Licensed under CC BY-NC-SA-4.0.

Social psychologists attend to all levels of analysis but—historically—this branch of psychology has emphasized the higher levels of analysis. Researchers in this field are drawn to questions related to relationships, groups, and culture. This means that they frame their research hypotheses in these terms. Imagine for a moment that you are a social researcher. In your daily life, you notice that older men, on average, seem to talk about their feelings less than do younger men. You might want to explore your hypothesis by recording natural conversations between males of different ages. This would allow you to see if there was evidence supporting your original observation. It would also allow you to begin to sift through all the factors that might influence this phenomenon: What happens when an older man talks to a younger man? What happens when an older man talks to a stranger versus his best friend? What happens when two highly educated men interact versus two working class men? Exploring each of these questions focuses on interactions, behavior, and culture rather than on perceptions, hormones, or DNA.

Social psychologists have developed unique methods for studying attitudes and behaviors that help answer questions that may not be possible to answer in a laboratory. Naturalistic observation of real world interactions, for example, would be a method well suited for understanding more about men and how they share their feelings.

In part, this focus on complex relationships and interactions is one of the things that makes research in social psychology so difficult. High quality research often involves the ability to control the environment, as in the case of laboratory experiments. The research laboratory, however; is artificial, and what happens there may not translate to the more natural circumstances of life. This is why social psychologists have developed their own set of unique methods for studying attitudes and social behavior. For example, they use naturalistic observation to see how people behave when they don’t know they are being watched. Whereas people in the laboratory might report that they personally hold no racist views or opinions (biases most people wouldn’t readily admit to), if you were to observe how close they sat next to people of other ethnicities while riding the bus, you might discover a behavioral clue to their actual attitudes and preferences.

Biswas-Diener, R. (2018). An introduction to the science of social psychology. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. DOI:nobaproject.com. Retrieved from http://nobaproject.com/modules/an-introduction-to-the-science-of-social-psychology. Licensed under CC BY-NC-SA-4.0.

Social Roles

One major social determinant of human behavior is our social roles. A social role is a pattern of behavior that is expected of a person in a given setting or group (Hare, 2003). Each one of us has several social roles. You may be, at the same time, a student, a parent, an aspiring teacher, a son or daughter, a spouse, and a lifeguard. How do these social roles influence your behavior? Social roles are defined by culturally shared knowledge. That is, nearly everyone in a given culture knows what behavior is expected of a person in a given role. For example, what is the social role for a student? If you look around a college classroom you will likely see students engaging in studious behavior, taking notes, listening to the professor, reading the textbook, and sitting quietly at their desks. Of course you may see students deviating from the expected studious behaviors such as texting on their phones or using Facebook on their laptops, but in all cases, the students that you observe are attending class—a part of the social role of students.

Social roles, and our related behavior, can vary across different settings. How do you behave when you are engaging in the role of son or daughter and attending a family function? Now imagine how you behave when you are engaged in the role of employee at your workplace. It is very likely that your behavior will be different. Perhaps you are more relaxed and outgoing with your family, making jokes and doing silly things. But at your workplace you might speak more professionally, and although you may be friendly, you are also serious and focused on getting the work completed. These are examples of how our social roles influence and often dictate our behavior to the extent that identity and personality can vary with context (that is, in different social groups) (Malloy, Albright, Kenny, Agatstein & Winquist, 1997).

Social Norms

As discussed previously, social roles are defined by a culture’s shared knowledge of what is expected behavior of an individual in a specific role. This shared knowledge comes from social norms. A social norm is a group’s expectation of what is appropriate and acceptable behavior for its members—how they are supposed to behave and think (Deutsch & Gerard, 1955; Berkowitz, 2004). How are we expected to act? What are we expected to talk about? What are we expected to wear? In our discussion of social roles we noted that colleges have social norms for students’ behavior in the role of student and workplaces have social norms for employees’ behaviors in the role of employee. Social norms are everywhere including in families, gangs, and on social media outlets. What are some social norms on Facebook?

Scripts

Because of social roles, people tend to know what behavior is expected of them in specific, familiar settings. A script is a person’s knowledge about the sequence of events expected in a specific setting (Schank & Abelson, 1977). How do you act on the first day of school, when you walk into an elevator, or are at a restaurant? For example, at a restaurant in the United States, if we want the server’s attention, we try to make eye contact. In Brazil, you would make the sound “psst” to get the server’s attention. You can see the cultural differences in scripts. To an American, saying “psst” to a server might seem rude, yet to a Brazilian, trying to make eye contact might not seem like an effective strategy. Scripts are important sources of information to guide behavior in given situations. Can you imagine being in an unfamiliar situation and not having a script for how to behave? This could be uncomfortable and confusing.

OpenStax, Self-presentation. OpenStax CNX. Dec 16, 2014 http://cnx.org/contents/a3e2787e-10c1-4e97-be22-0bd93b609b70@5. Retrieved from https://cnx.org/contents/Sr8Ev5Og@5.52:o-J4fhDB@5/Self-presentation. Licensed under CC BY-4.0.

Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison Experiment

The famous Stanford prison experiment, conducted by social psychologist Philip Zimbardo and his colleagues at Stanford University, demonstrated the power of social roles, social norms, and scripts. In the summer of 1971, an advertisement was placed in a California newspaper asking for male volunteers to participate in a study about the psychological effects of prison life. More than 70 men volunteered, and these volunteers then underwent psychological testing to eliminate candidates who had underlying psychiatric issues, medical issues, or a history of crime or drug abuse. The pool of volunteers was whittled down to 24 healthy male college students. Each student was paid $15 per day and was randomly assigned to play the role of either a prisoner or a guard in the study.

A mock prison was constructed in the basement of the psychology building at Stanford. Participants assigned to play the role of prisoners were “arrested” at their homes by Palo Alto police officers, booked at a police station, and subsequently taken to the mock prison. The experiment was scheduled to run for several weeks. To the surprise of the researchers, both the “prisoners” and “guards” assumed their roles with zeal. In fact, on day 2, some of the prisoners revolted, and the guards quelled the rebellion by threatening the prisoners with night sticks. In a relatively short time, the guards came to harass the prisoners in an increasingly sadistic manner, through a complete lack of privacy, lack of basic comforts such as mattresses to sleep on, and through degrading chores and late-night counts.

Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:%D0%A1%D1%82%D0%B5%D0%BD%D1%84%D0%BE%D1%80%D0%B4.jpg. Licensed under CC BY-SA-4.0.

The prisoners, in turn, began to show signs of severe anxiety and hopelessness—they began tolerating the guards’ abuse. Even the Stanford professor who designed the study and was the head researcher, Philip Zimbardo, found himself acting as if the prison was real and his role, as prison supervisor, was real as well. After only six days, the experiment had to be ended due to the participants’ deteriorating behavior. Zimbardo explained,

At this point it became clear that we had to end the study. We had created an overwhelmingly powerful situation—a situation in which prisoners were withdrawing and behaving in pathological ways, and in which some of the guards were behaving sadistically. Even the “good” guards felt helpless to intervene, and none of the guards quit while the study was in progress. Indeed, it should be noted that no guard ever came late for his shift, called in sick, left early, or demanded extra pay for overtime work. (Zimbardo, 2013)

The Stanford prison experiment demonstrated the power of social roles, norms, and scripts in affecting human behavior. The guards and prisoners enacted their social roles by engaging in behaviors appropriate to the roles: The guards gave orders and the prisoners followed orders. Social norms require guards to be authoritarian and prisoners to be submissive. When prisoners rebelled, they violated these social norms, which led to upheaval. The specific acts engaged by the guards and the prisoners derived from scripts. For example, guards degraded the prisoners by forcing them do push-ups and by removing all privacy. Prisoners rebelled by throwing pillows and trashing their cells. Some prisoners became so immersed in their roles that they exhibited symptoms of mental breakdown; however, according to Zimbardo, none of the participants suffered long term harm (Alexander, 2001).

OpenStax, Self-presentation. OpenStax CNX. Dec 16, 2014 http://cnx.org/contents/a3e2787e-10c1-4e97-be22-0bd93b609b70@5. Retrieved from https://cnx.org/contents/Sr8Ev5Og@5.52:o-J4fhDB@5/Self-presentation. Licensed under CC BY-4.0.

Social Psychology-Video

Yondaime H. (2015, October 8). Social psychology intro. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NgAHgli3D5Q. Standard YouTube License.

Marika Lamoreaux. (2015, February 13). Social influence 1 roles and norms. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uEeQn6HSrP8&t=23s. Standard YouTube License.

Khanacademymedicine. (2015, April 3). Zimbardo prison study the Stanford prison experiment: Behavior-MCAT Khan Academy. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d2TCfex1aFw. Standard YouTube License.

Summary

Social psychology is the branch of psychological science mainly concerned with understanding how the presence of others affects our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, and social psychologists are scientists who are interested in understanding the ways we relate to one another, and the impact these relationships have on us, individually and collectively. Not only can social psychology research lead to a better understanding of personal relationships, but it can lead to practical solutions for many social skills. Lawmakers, teachers and parents, therapists, and policy makers can all use this science to help develop societies with less conflict and more social support. (Biswas-Diener, 2018)

In this section we studied some intrapersonal topics of social psychology (those that pertain to the individual), including social roles, norms and scripts, and we discussed how human behavior is largely influenced by these factors. In order to know how to act in a given situation, we have shared cultural knowledge of how to behave depending on our role in society. Social norms dictate the behavior that is appropriate or inappropriate for each role. Each social role has scripts that help humans learn the sequence of appropriate behaviors in a given setting. The famous Stanford prison experiment is an example of how the power of the situation can dictate the social roles, norms, and scripts we follow in a given situation, even if this behavior is contrary to our typical behavior. (OpenStax, 2014)