Altruism and Aggression

Introduction

In the previous section we focused on the principles of social cognition and understanding ourselves and others. Humans have developed a variety of social skills that enhance our ability to successfully interact with others. In this section we will consider the social psychology of interpersonal relationships, including the behaviors of altruism and aggression. We will explore how genetic and environmental factors contribute to human altruism, as well as review the biological and social influences on aggression. We will discuss how humans are often helpful, even when that helping comes at some cost to ourselves. While we can be helpful and altruistic, we are also able to be aggressive if we feel the situation warrants it. Aggression may be physical or nonphysical. Aggression is activated in large part by the amygdala and regulated by the prefrontal cortex. Testosterone is associated with increased aggression in both males and females. Aggression is also caused by negative experiences and emotions, including frustration, pain, and heat. As predicted by principles of observational learning, research evidence makes it very clear that, on average, people who watch violent behavior become more aggressive.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Interacting with Others: Helping and Hurting

Altruism

Altruism refers to any behavior that is designed to increase another person’s welfare, and particularly those actions that do not seem to provide a direct reward to the person who performs them (Dovidio, Piliavin, Schroeder, & Penner, 2006). Altruism occurs when we stop to help a stranger who has been stranded on the highway, when we volunteer at a homeless shelter, or when we donate to a charity. According to a survey given by an established coalition that studies and encourages volunteering, in 2001 over 83 million American adults reported that they helped others by volunteering, and did so an average of 3.6 hours per week. The survey estimated that the value of the volunteer time that was given was over 239 billion dollars. (http://www.independentsector.org)

The tendency to help others in need is in part a functional evolutionary adaptation. Although helping others can be costly to us as individuals, helping people who are related to us can perpetuate our own genes (Madsen et al., 2007; McAndrew, 2002; Stewart-Williams, 2007). Burnstein, Crandall, and Kitayama (1994) found that students indicated they would be more likely to help a person who was closely related to them (e.g., a sibling, parent, or child) than they would be to help a person who was more distantly related (e.g., a niece, nephew, uncle, or grandmother). People are more likely to donate kidneys to relatives than to strangers (Borgida, Conner, & Manteufel, 1992), and even children indicate that they are more likely to help their siblings than they are to help a friend (Tisak & Tisak, 1996).

Retrieved from http://www.thinkstockphotos.com/image/stock-photo-woman-feeding-older-woman/78655680/popup?sq=woman%20feeding%20elderly%20woman/f=CPIHVX/p=2/s=DynamicRank.

Although it makes evolutionary sense that we would help people who we are related to, why would we help people to whom we not related? One explanation for such behavior is based on the principle of reciprocal altruism (Krebs & Davies, 1987; Trivers, 1971). Reciprocal altruism is the principle that, if we help other people now, those others will return the favor should we need their help in the future. By helping others, we both increase our chances of survival and reproductive success and help others increase their survival too. Over the course of evolution, those who engage in reciprocal altruism should be able to reproduce more often than those who do not, thus enabling this kind of altruism to continue.

We also learn to help by modeling the helpful behavior of others. Although people frequently worry about the negative impact of the violence that is seen on TV, there is also a great deal of helping behavior shown on television. Smith et al. (2006) found that 73% of TV shows had some altruism, and that about three altruistic behaviors were shown every hour. Furthermore, the prevalence of altruism was particularly high in children’s shows. But just as viewing altruism can increase helping, modeling of behavior that is not altruistic can decrease altruism. For instance, Anderson and Bushman (2001) found that playing violent video games led to a decrease in helping.

We are more likely to help when we receive rewards for doing so and less likely to help when helping is costly. Parents praise their children who share their toys with others, and may reprimand children who are selfish. We are more likely to help when we have plenty of time than when we are in a hurry (Darley & Batson, 1973). Another potential reward is the status we gain as a result of helping. When we act altruistically, we gain a reputation as a person with high status who is able and willing to help others, and this status makes us more desirable in the eyes of others (Hardy & Van Vugt, 2006).

The outcome of the reinforcement and modeling of altruism is the development of social norms about helping—standards of behavior that we see as appropriate and desirable regarding helping. The reciprocity norm reminds us that we should follow the principles of reciprocal altruism. If someone helps us, then we should help them in the future, and we should help people now with the expectation that they will help us later if we need it. The reciprocity norm is found in everyday adages such as “Scratch my back and I’ll scratch yours” and in religious and philosophical teachings such as the “Golden Rule”: “Do unto other as you would have them do unto you.”

Because helping based on the reciprocity norm is based on the return of earlier help and the expectation of a future return from others, it might not seem like true altruism. We might hope that our children internalize another relevant social norm that seems more altruistic: the social responsibility norm. The social responsibility norm tells us that we should try to help others who need assistance, even without any expectation of future paybacks. The teachings of many religions are based on the social responsibility norm; that we should, as good human beings, reach out and help other people whenever we can.

How the Presence of Others Can Reduce Helping

Late at night on March 13, 1964, 28-year-old Kitty Genovese was murdered within a few yards of her apartment building in New York City after a violent fight with her killer in which she struggled and screamed. When the police interviewed Kitty’s neighbors about the crime, they discovered that 38 of the neighbors indicated that they had seen or heard the fight occurring but not one of them had bothered to intervene, and only one person had called the police.

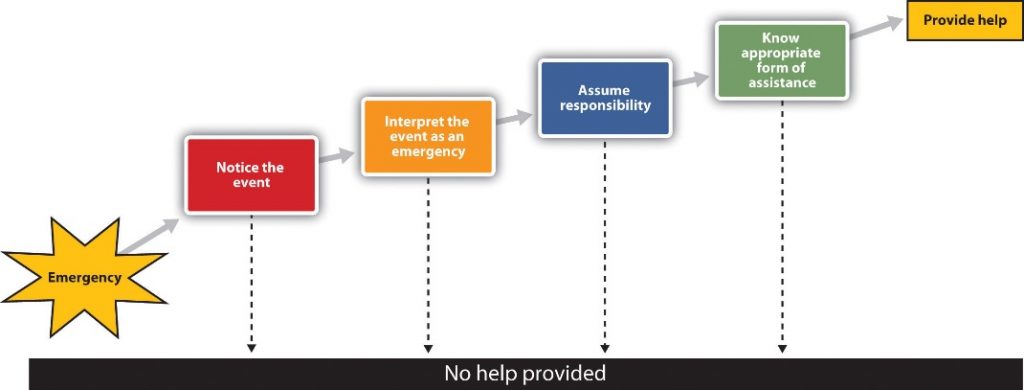

Two social psychologists, Bibb Latané and John Darley, were interested in the factors that influenced people to help (or to not help) in such situations (Latané & Darley, 1968). They developed a model that took into consideration the important role of the social situation in determining helping. The model has been extensively tested in many studies, and there is substantial support for it. Social psychologists have discovered that it was the 38 people themselves that contributed to the tragedy, because people are less likely to notice, interpret, and respond to the needs of others when they are with others than they are when they are alone.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

The first step in the model is noticing the event. Latané and Darley (1968) demonstrated the important role of the social situation in noticing by asking research participants to complete a questionnaire in a small room. Some of the participants completed the questionnaire alone, whereas others completed the questionnaire in small groups in which two other participants were also working on questionnaires. A few minutes after the participants had begun the questionnaires, the experimenters started to let some white smoke come into the room through a vent in the wall. The experimenters timed how long it took before the first person in the room looked up and noticed the smoke.

The people who were working alone noticed the smoke in about 5 seconds, and within 4 minutes most of the participants who were working alone had taken some action. On the other hand, on average, the first person in the group conditions did not notice the smoke until over 20 seconds had elapsed. And, although 75% of the participants who were working alone reported the smoke within 4 minutes, the smoke was reported in only 12% of the groups by that time. In fact, in only 3 out of the 8 groups did anyone report the smoke, even after it had filled the room. You can see that the social situation has a powerful influence on noticing; we simply don’t see emergencies when other people are with us.

Even if we notice an emergency, we might not interpret it as one. Were the cries of Kitty Genovese really calls for help, or were they simply an argument with a boyfriend? The problem is compounded when others are present, because when we are unsure how to interpret events we normally look to others to help us understand them, and at the same time they are looking to us for information. The problem is that each bystander thinks that other people aren’t acting because they don’t see an emergency. Believing that the others know something that they don’t, each observer concludes that help is not required.

Even if we have noticed the emergency and interpret it as being one, this does not necessarily mean that we will come to the rescue of the other person. We still need to decide that it is our responsibility to do something. The problem is that when we see others around, it is easy to assume that they are going to do something, and that we don’t need to do anything ourselves. Diffusion of responsibility occurs when we assume that others will take action and therefore we do not take action ourselves. The irony again, of course, is that people are more likely to help when they are the only ones in the situation than when there are others around.

Perhaps you have noticed diffusion of responsibility if you participated in an Internet users group where people asked questions of the other users. Did you find that it was easier to get help if you directed your request to a smaller set of users than when you directed it to a larger number of people? Markey (2000) found that people received help more quickly (in about 37 seconds) when they asked for help by specifying a participant’s name than when no name was specified (51 seconds).

The final step in the helping model is knowing how to help. Of course, for many of us the ways to best help another person in an emergency are not that clear; we are not professionals and we have little training in how to help in emergencies. People who do have training in how to act in emergencies are more likely to help, whereas the rest of us just don’t know what to do, and therefore we may simply walk by. On the other hand, today many people have cell phones, and we can do a lot with a quick call; in fact, a phone call made in time might have saved Kitty Genovese’s life.

Anderson, C. A., & Bushman, B. J. (2001). Effects of violent video games on aggressive behavior, aggressive cognition, aggressive affect, physiological arousal, and prosocial behavior: A meta-analytic review of the scientific literature. Psychological Science, 12(5), 353–359.

Borgida, E., Conner, C., & Manteufel, L. (Eds.). (1992). Understanding living kidney donation: A behavioral decision-making perspective. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Burnstein, E., Crandall, C., & Kitayama, S. (1994). Some neo-Darwinian decision rules for altruism: Weighing cues for inclusive fitness as a function of the biological importance of the decision. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(5), 773–789.

Darley, J. M., & Batson, C. D. (1973). “From Jerusalem to Jericho”: A study of situational and dispositional variables in helping behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 27(1), 100–108.

Dovidio, J. F., Piliavin, J. A., Schroeder, D. A., & Penner, L. (2006). The social psychology of prosocial behavior. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Hardy, C. L., & Van Vugt, M. (2006). Nice guys finish first: The competitive altruism hypothesis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32(10), 1402–1413.

Krebs, J. R., & Davies, N. B. (1987). An introduction to behavioural ecology (2nd ed.). Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates; Trivers, R. L. (1971). The evolution of reciprocal altruism. Quarterly Review of Biology, 46, 35–57.

Latané, B., & Darley, J. M. (1968). Group inhibition of bystander intervention in emergencies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 10(3), 215–221.

Madsen, E. A., Tunney, R. J., Fieldman, G., Plotkin, H. C., Dunbar, R. I. M., Richardson, J.-M.,…McFarland, D. (2007). Kinship and altruism: A cross-cultural experimental study. British Journal of Psychology, 98(2), 339–359; McAndrew, F. T. (2002). New evolutionary perspectives on altruism: Multilevel-selection and costly-signaling theories. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 11(2), 79–82; Stewart-Williams, S. (2007). Altruism among kin vs. nonkin: Effects of cost of help and reciprocal exchange. Evolution and Human Behavior, 28(3), 193–198.

Markey, P. M. (2000). Bystander intervention in computer-mediated communication. Computers in Human Behavior, 16(2), 183–188.

Smith, S. W., Smith, S. L., Pieper, K. M., Yoo, J. H., Ferris, A. L., Downs, E.,…Bowden, B. (2006). Altruism on American television: Examining the amount of, and context surrounding, acts of helping and sharing. Journal of Communication, 56(4), 707–727.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Tisak, M. S., & Tisak, J. (1996). My sibling’s but not my friend’s keeper: Reasoning about responses to aggressive acts. Journal of Early Adolescence, 16(3), 324–339.

Human Aggression

Aggression is behavior that is intended to harm another individual. Aggression may occur in the heat of the moment, for instance, when a jealous lover strikes out in rage or the sports fans at a university light fires and destroy cars after an important basketball game. Or it may occur in a more cognitive, deliberate, and planned way, such as the aggression of a bully who steals another child’s toys, a terrorist who kills civilians to gain political exposure, or a hired assassin who kills for money. Not all aggression is physical. Aggression also occurs in nonphysical ways, as when children exclude others from activities, call them names, or spread rumors about them. Paquette and Underwood (1999) found that both boys and girls rated nonphysical aggression such as name-calling as making them feel more “sad and bad” than did physical aggression.

We may aggress against others in part because it allows us to gain access to valuable resources such as food, territory, and desirable mates or to protect ourselves from direct attack by others. If aggression helps in the survival of our genes, then the process of natural selection may well have caused humans, as it would any other animal, to be aggressive (Buss & Duntley, 2006). The causes of our aggression, then, are both socially determined and part of our genetic code. Because our genes determine our aggression, we will not be surprised to find that aggression has strong roots in the oldest parts of the brain and in the chemicals that circulate in our bodies.

Within the brain, aggression is controlled by the amygdala. One of the primary functions of the amygdala is to help us learn to associate stimuli with the rewards and punishments that they may provide. The amygdala is particularly activated in our responses to stimuli that we see as threatening and fear-arousing. When the amygdala is stimulated, in either humans or animals, the organism becomes more aggressive. But just because we can aggress does not mean that we will aggress. It is not necessarily evolutionarily adaptive to aggress in all situations. Neither people nor animals are always aggressive; they rely on aggression only when they feel that they absolutely need to (Berkowitz, 1993). The prefrontal cortex serves as a control center on aggression; when it is more highly activated, we are more able to control our aggressive impulses. Research has found that the cerebral cortex is less active in murderers and death row inmates, suggesting that violent crime may be caused at least in part by a failure or reduced ability to regulate aggression (Davidson, Putnam, & Larson, 2000).

Hormones are also important in regulating aggression. Most important in this regard is the male sex hormone testosterone, which is associated with increased aggression in both males and females. Research conducted on a variety of animals has found a positive correlation between levels of testosterone and aggression. High testosterone levels, particularly for men, correlates with delinquency and bullying. This relationship seems to be weaker among humans than among animals, yet it is still significant (Dabbs, Hargrove, & Heusel, 1996).

Consuming alcohol increases the likelihood that people will respond aggressively to provocations, and even people who are not normally aggressive may react with aggression when they are intoxicated (Graham, Osgood, Wells, & Stockwell, 2006). You will not be surprised to hear that almost half of violent crimes and about three-quarters of spousal abuse crimes relate to the use of alcohol. Alcohol reduces the ability of people who have consumed it to inhibit their aggression because when people are intoxicated, they become more self-focused and less aware of the social constraints that normally prevent them from engaging aggressively (Bushman & Cooper, 1990; Steele & Southwick, 1985).

Negative Experiences Increase Aggression

If I were to ask you about the times that you have been aggressive, I bet that you would tell me that many of them occurred when you were angry, in a bad mood, tired, in pain, sick, or frustrated. And you would be right—we are much more likely to aggress when we are experiencing negative emotions. One important determinant of aggression is frustration. When we are frustrated we may lash out at others, even at people who did not cause the frustration. In some cases, the aggression is displaced aggression, which is aggression that is directed at an object or person other than the person who caused the frustration. Other negative emotions also increase aggression. Griffit and Veitch (1971) had students complete questionnaires in rooms in which the heat was at a normal temperature or in which the temperature was over 90 degrees Fahrenheit. The students in the latter conditions expressed significantly more hostility. Aggression is greater on hot days than it is on cooler days and during hot years than during cooler years, and most violent riots occur during the hottest days of the year (Bushman, Wang, & Anderson, 2005). Pain also increases aggression (Berkowitz, 1993).

If we are aware that we are feeling negative emotions, we might think that we could release those emotions in a relatively harmless way, such as by punching a pillow or kicking something, with the hopes that doing so will release our aggressive tendencies. Catharsis—the idea that observing or engaging in less harmful aggressive actions will reduce the tendency to aggress later in a more harmful way—has been considered by many as a way of decreasing violence, and it was an important part of the theories of Sigmund Freud. As far as social psychologists have been able to determine, however; catharsis simply does not work. Rather than decreasing aggression, engaging in aggressive behaviors of any type increases the likelihood of later aggression.

Bushman, Baumeister, and Stack (1999) first angered their research participants by having another student insult them. Then half of the participants were allowed to engage in a cathartic behavior: They were given boxing gloves and then got a chance to hit a punching bag for 2 minutes. Then all the participants played a game with the person who had insulted them earlier in which they had a chance to blast the other person with a painful blast of white noise. Contrary to the catharsis hypothesis, the students who had punched the punching bag set a higher noise level and delivered longer bursts of noise than the participants who did not get a chance to hit the punching bag. It seems that if we hit a punching bag, punch a pillow, or scream as loud as we can to release our frustration, the opposite may occur—rather than decreasing aggression, these behaviors in fact increase it.

Does Viewing Violent Media Increase Aggression?

The average American watches over 4 hours of television every day, and these programs contain a substantial amount of aggression. At the same time, children are also exposed to violence in movies and video games, as well as in popular music and music videos that include violent lyrics and imagery. But does watching violence and playing violent video games increase aggressive behavior? The answer seems to be that, on average, people who watch violent behavior become more aggressive, but that this relationship is not very strong. The evidence supporting this relationship comes from many studies conducted over many years using both correlational designs as well as laboratory studies in which people have been randomly assigned to view either violent or nonviolent material (Anderson et al., 2003; Ferguson, 2015).

Retrieved from https://www.maxpixel.net/Gamer-Video-Entertainment-Game-Remote-Technology-2294201. Licensed under CC0.

Viewing violent behavior probably increases aggression in part through observational learning. Another outcome of viewing large amounts of violent material is desensitization, which is the tendency over time to show weaker emotional responses to emotional stimuli. When we first see violence, we are likely to be shocked, aroused, and even repulsed by it. However, over time, as we see more and more violence, we become habituated to it, such that the subsequent exposures produce fewer and fewer negative emotional responses. Continually viewing violence also makes us more distrustful and more likely to behave aggressively (Bartholow, Bushman, & Sestir, 2006; Nabi & Sullivan, 2001).

Of course, not everyone who views violent material becomes aggressive; individual differences also matter. People who experience a lot of negative affect and who feel that they are frequently rejected by others whom they care about are more aggressive (Downey, Irwin, Ramsay, & Ayduk, 2004). People with inflated or unstable self-esteem are more prone to anger and are highly aggressive when their high self-image is threatened (Baumeister, Smart, & Boden, 1996). For instance, classroom bullies are those children who always want to be the center of attention, who think a lot of themselves, and who cannot take criticism (Salmivalli & Nieminen, 2002). Bullies are highly motivated to protect their inflated self-concepts, and they react with anger and aggression when it is threatened.

There is a culturally universal tendency for men to be more physically violent than women (Archer & Coyne, 2005; Crick & Nelson, 2002). Worldwide, about 99% of rapes and about 90% of robberies, assaults, and murders are committed by men (Graham & Wells, 2001). These sex differences do not imply that women are never aggressive. Both men and women respond to insults and provocation with aggression; the differences between men and women are smaller after they have been frustrated, insulted, or threatened (Bettencourt & Miller, 1996).

Archer, J., & Coyne, S. M. (2005). An integrated review of indirect, relational, and social aggression. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 9(3), 212–230; Crick, N. R., & Nelson, D. A. (2002). Relational and physical victimization within friendships: Nobody told me there’d be friends like these. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 30(6), 599–607.

Bartholow, B. D., Bushman, B. J., & Sestir, M. A. (2006). Chronic violent video game exposure and desensitization to violence: Behavioral and event-related brain potential data. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 42(4), 532–539; Nabi, R. L., & Sullivan, J. L. (2001). Does television viewing relate to engagement in protective action against crime? A cultivation analysis from a theory of reasoned action perspective. Communication Research, 28(6), 802–825.

Baumeister, R. F., Smart, L., & Boden, J. M. (1996). Relation of threatened egotism to violence and aggression: The dark side of high self-esteem. Psychological Review, 103(1), 5–33.

Berkowitz, L. (1993). Aggression: Its causes, consequences and control. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Berkowitz, L. (1993). Pain and aggression: Some findings and implications. Motivation and Emotion, 17(3), 277–293.

Bettencourt, B., & Miller, N. (1996). Gender differences in aggression as a function of provocation: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 119, 422–447.

Bushman, B. J., Baumeister, R. F., & Stack, A. D. (1999). Catharsis, aggression, and persuasive influence: Self-fulfilling or self-defeating prophecies? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(3), 367–376.

Bushman, B. J., & Cooper, H. M. (1990). Effects of alcohol on human aggression: An integrative research review. Psychological Bulletin, 107(3), 341–354; Steele, C. M., & Southwick, L. (1985). Alcohol and social behavior I: The psychology of drunken excess. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48(1), 18–34.

Bushman, B. J., Wang, M. C., & Anderson, C. A. (2005). Is the curve relating temperature to aggression linear or curvilinear? Assaults and temperature in Minneapolis reexamined. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89(1), 62–66.

Buss, D. M., & Duntley, J. D. (Eds.). (2006). The Evolution of aggression. Madison, CT: Psychosocial Press.

Dabbs, J. M. Jr., Hargrove, M. F., & Heusel, C. (1996). Testosterone differences among college fraternities: Well-behaved vs. rambunctious. Personality and Individual Differences, 20(2), 157–161.

Davidson, R. J., Putnam, K. M., & Larson, C. L. (2000). Dysfunction in the neural circuitry of emotion regulation—A possible prelude to violence. Science, 289(5479), 591–594.

Downey, G., Irwin, L., Ramsay, M., & Ayduk, O. (Eds.). (2004). Rejection sensitivity and girls’ aggression. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

Ferguson C. J. (2015a). Do angry birds make for angry children? A meta-analysis of video game influences on children’s and adolescents’ aggression, mental health, prosocial behavior, and academic performance. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10, 646–666. Anderson, C. A., Berkowitz, L., Donnerstein, E., Huesmann, L. R., Johnson, J. D., Linz, D.,…Wartella, E. (2003). The influence of media violence on youth. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 4(3), 81–110.

Graham, K., Osgood, D. W., Wells, S., & Stockwell, T. (2006). To what extent is intoxication associated with aggression in bars? A multilevel analysis. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 67(3), 382–390.

Graham, K., & Wells, S. (2001). The two worlds of aggression for men and women. Sex Roles, 45(9–10), 595–622.

Griffit, W., & Veitch, R. (1971). Hot and crowded: Influence of population density and temperature on interpersonal affective behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 17(1), 92–98.

Paquette, J. A., & Underwood, M. K. (1999). Gender differences in young adolescents’ experiences of peer victimization: Social and physical aggression. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 45(2), 242–266.

Salmivalli, C., & Nieminen, E. (2002). Proactive and reactive aggression among school bullies, victims, and bully-victims. Aggressive Behavior, 28(1), 30–44.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Interacting with Others: Help and Hurting-Video

CrashCourse. (2014, November 24). Aggression v. altruism: Crash course psychology #40. [Video Files]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XoTx7Rt4dig. Standard YouTube License.

Mhssocialstudies1. (2013, April 17). Ap psych: Aggression and altruism. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4qchHyz9mEY. Standard YouTube License.

Summary

The tendency to help others in need is in part a functional evolutionary adaptation. We help others to benefit ourselves and to benefit the others. Reciprocal altruism leads us to help others now with the expectation those others will return the favor should we need their help in the future. The outcome of the reinforcement and modeling of altruism is the development of social norms about helping, including the reciprocity norm and the social responsibility norm. Latané and Darley’s model of helping proposes that the presence of others can reduce noticing, interpreting, and responding to emergencies.

Aggression may be physical or nonphysical. Aggression is activated in large part by the amygdala and regulated by the prefrontal cortex. Testosterone is associated with increased aggression in both males and females. Aggression is also caused by negative experiences and emotions, including frustration, pain, and heat. As predicted by principles of observational learning, research evidence makes it very clear that, on average, people who watch violent behavior become more aggressive. In addition, the experience of negative emotions tends to increase violence. Children who witness violence are more likely to be aggressive. Another outcome of viewing large amounts of violent material is desensitization, which is the tendency over time to show weaker emotional responses to emotional stimuli.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.