Attachment Theory

Introduction

In this section, we will explore theories of attachment. One of the most important behaviors a child must learn is how to be accepted by others—the development of close and meaningful social relationships. The emotional bonds that we develop with those with whom we feel closest, and particularly the bonds that an infant develops with the mother or primary caregiver, are referred to as attachment (Cassidy & Shaver, 1999). Attachment theory is a model that seeks to capture the emotional bonds that connects one person to another across time and space. The attachment theory originated with the work of John Bowlby. John Bowlby was a British psychiatrist who treated children with emotional issues. He viewed attachment as part of the evolutionary processes and was interested in separation anxiety and the distress that children experience when separated from their primary caregivers.

Image retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Attachment_theory#/media/File:Children_marbles.jpg. Licensed under CC-BY-2.0.

In 1970s, psychologist Mary Ainsworth expanded upon the work of Bowlby. She explored the effects of attachment on behavior in her study “Strange Situation.” In this study, Ainsworth and her colleagues observed children between the ages of 12 -18 months and the response when the child was left alone and then reunited with their mothers. Based on the responses from the children, Ainsworth described there major types of attachment; secure attachment, ambivalent-insecure attachment and avoidance-insecure attachment.

Cassidy, J. E., & Shaver, P. R. E. (1999). Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. New York, NY: Guilford

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Attachment Theory

As late as the 1930s, psychologists believed that children who were raised in institutions such as orphanages, and who received good physical care and proper nourishment, would develop normally, even if they had little interaction with their caretakers. But studies by the developmental psychologist John Bowlby (1953) and others showed that these children did not develop normally—they were usually sickly, emotionally slow, and generally unmotivated. These observations helped make it clear that normal infant development requires successful attachment with a caretaker.

In one classic study showing the importance of attachment, Wisconsin University psychologists Harry and Margaret Harlow investigated the responses of young monkeys, separated from their biological mothers, to two surrogate mothers introduced to their cages. One—the wire mother—consisted of a round wooden head, a mesh of cold metal wires, and a bottle of milk from which the baby monkey could drink. The second mother was a foam-rubber form wrapped in a heated terry-cloth blanket. The Harlows found that, although the infant monkeys went to the wire mother for food, they overwhelmingly preferred and spent significantly more time with the warm terry-cloth mother that provided no food but did provide comfort (Harlow, 1958).

Image retrieved from https://www.maxpixel.net/Macaque-Mammal-Animal-Rhesus-Nature-Monkey-India-1419294. Licensed under CC0-1.0.

The Harlows’ studies confirmed that babies have social as well as physical needs. Both monkeys and human babies need a

secure base that allows them to feel safe. From this base, they can gain the confidence they need to venture out and explore their worlds. Erikson was in agreement on the importance of a secure base, arguing that the most important goal of infancy was the development of a basic sense of trust in one’s caregivers.

Developmental psychologist Mary Ainsworth, a student of John Bowlby, was interested in studying the development of attachment in infants. Ainsworth created a laboratory test that measured an infant’s attachment to his or her parent. The test is called the strange situation because it is conducted in a context that is unfamiliar to the child and therefore likely to heighten the child’s need for his or her parent (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978). During the procedure, which lasts about 20 minutes, the parent and the infant are first left alone, while the infant explores the room full of toys. Then a strange adult enters the room and talks for a minute to the parent, after which the parent leaves the room. The stranger stays with the infant for a few minutes, and then the parent again enters and the stranger leaves the room. During the entire session, a video camera records the child’s behaviors, which are later coded by trained coders.

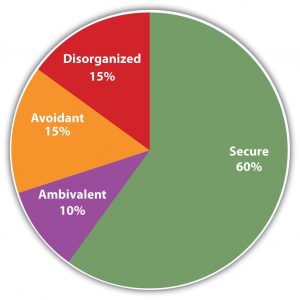

On the basis of their behaviors, the children are categorized into one of four groups, where each group reflects a different kind of attachment relationship with the caregiver. A child with a secure attachment style usually explores freely while the mother is present and engages with the stranger. The child may be upset when the mother departs but is also happy to see the mother return.

A child with an ambivalent (sometimes called insecure-resistant) attachment style is wary about the situation in general, particularly the stranger, and stays close or even clings to the mother rather than exploring the toys. When the mother leaves, the child is extremely distressed and is ambivalent when she returns. The child may rush to the mother but then fail to cling to her when she picks up the child.

A child with an avoidant (sometimes called insecure-avoidant) attachment style will avoid or ignore the mother, showing little emotion when the mother departs or returns. The child may run away from the mother when she approaches. The child will not explore very much, regardless of who is there, and the stranger will not be treated much differently from the mother.

Finally, a child with a disorganized attachment style seems to have no consistent way of coping with the stress of the strange situation—the child may cry during the separation but avoid the mother when she returns, or the child may approach the mother but then freeze or fall to the floor. Although some cultural differences in attachment styles have been found (Rothbaum, Weisz, Pott, Miyake, & Morelli, 2000), research has also found that the proportion of children who fall into each of the attachment categories is relatively constant across cultures.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld

You might wonder whether differences in attachment style are determined more by the child (nature) or more by the parents (nurture). Most developmental psychologists believe that socialization is primary, arguing that a child becomes securely attached when the mother is available and able to meet the needs of the child in a responsive and appropriate manner, but that the insecure styles occur when the mother is insensitive and responds inconsistently to the child’s needs. In a direct test of this idea, Dutch researcher Dymphna van den Boom (1994) randomly assigned some babies’ mothers to a training session in which they learned to better respond to their children’s needs. The research found that, after the training, these mothers’ babies were more likely to show a secure attachment style in comparison to the mothers in a control group that did not receive training.

But the attachment behavior of the child is also likely influenced, at least in part, by temperament, the innate personality characteristics of the infant. Some children are warm, friendly, and responsive, whereas others tend to be more irritable, less manageable, and difficult to console. These differences may also play a role in attachment (Gillath, Shaver, Baek, & Chun, 2008; Seifer, Schiller, Sameroff, Resnick, & Riordan, 1996). Taken together, it seems safe to say that attachment, like most other developmental processes, is affected by an interplay of genetic and socialization influences.

Ainsworth, M. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Bowlby, J. (1953). Some pathological processes set in train by early mother-child separation. Journal of Mental Science, 99, 265–272.

Gillath, O., Shaver, P. R., Baek, J.-M., & Chun, D. S. (2008). Genetic correlates of adult attachment style. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(10), 1396–1405; Seifer, R., Schiller, M., Sameroff, A. J., Resnick, S., & Riordan, K. (1996). Attachment, maternal sensitivity, and infant temperament during the first year of life. Developmental Psychology, 32(1), 12–25.

Harlow, H. (1958). The nature of love. American Psychologist, 13, 573–685.

Rothbaum, F., Weisz, J., Pott, M., Miyake, K., & Morelli, G. (2000). Attachment and culture: Security in the United States and Japan. American Psychologist, 55(10), 1093–1104.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld

van den Boom, D. C. (1994). The influence of temperament and mothering on attachment and exploration: An experimental manipulation of sensitive responsiveness among lower-class mothers with irritable infants. Child Development, 65(5), 1457–1476.

Research Focus: Using a Longitudinal Research Design to Assess the Stability of Attachment

You might wonder whether the attachment style displayed by infants has much influence later in life. Research has found that the attachment styles of children predict their emotions and their behaviors many years later (Cassidy & Shaver, 1999). Psychologists have studied the persistence of attachment styles over time using longitudinal research designs—research designs in which individuals in the sample are followed and contacted over an extended period of time, often over multiple developmental stages.

In one such study, Waters, Merrick, Treboux, Crowell, and Albersheim (2000) examined the extent of stability and change in attachment patterns from infancy to early adulthood. In their research, 60 middle-class infants who had been tested in the strange situation at 1 year of age were re-contacted 20 years later and interviewed using a measure of adult attachment. Waters and colleagues found that 72% of the infants received the same secure versus insecure attachment classification in early adulthood as they had received as infants. The adults who changed categorization (usually from secure to insecure) were primarily those who had experienced traumatic events, such as the death or divorce of parents, severe illnesses (contracted by the parents or the children themselves), or physical or sexual abuse by a family member.

In addition to finding that people generally display the same attachment style over time, longitudinal studies have also found that the attachment classification received in infancy (as assessed using the strange situation or other measures) predicts many childhood and adult behaviors. Securely attached infants have closer, more harmonious relationship with peers, are less anxious and aggressive, and are better able to understand others’ emotions than are those who were categorized as insecure as infants (Lucas-Thompson & Clarke-Stewart, (2007). And securely attached adolescents also have more positive peer and romantic relationships than their less securely attached counterparts (Carlson, Sroufe, & Egeland, 2004).

Conducting longitudinal research is a very difficult task, but one that has substantial rewards. When the sample is large enough and the time frame long enough, the potential findings of such a study can provide rich and important information about how people change over time and the causes of those changes. The drawbacks of longitudinal studies include the cost and the difficulty of finding a large sample that can be tracked accurately over time and the time (many years) that it takes to get the data. In addition, because the results are delayed over an extended period, the research questions posed at the beginning of the study may become less relevant over time as the research continues.

Cross-sectional research designs represent an alternative to longitudinal designs. In a cross-sectional research design, age comparisons are made between samples of different people at different ages at one time. In one example, Jang, Livesley, and Vernon (1996) studied two groups of identical and nonidentical (fraternal) twins, one group in their 20s and the other group in their 50s, to determine the influence of genetics on personality. They found that genetics played a more significant role in the older group of twins, suggesting that genetics became more significant for personality in later adulthood.

Cross-sectional studies have a major advantage in that the scientist does not have to wait for years to pass to get results. On the other hand, the interpretation of the results in a cross-sectional study is not as clear as those from a longitudinal study, in which the same individuals are studied over time. Most important, the interpretations drawn from cross-sectional studies may be confounded by cohort effects. Cohort effects refer to the possibility that differences in cognition or behavior at two points in time may be caused by differences that are unrelated to the changes in age. The differences might instead be due to environmental factors that affect an entire age group.

For instance, in the study by Jang, Livesley, and Vernon (1996) that compared younger and older twins, cohort effects might be a problem. The two groups of adults necessarily grew up in different time periods, and they may have been differentially influenced by societal experiences, such as economic hardship, the presence of wars, or the introduction of new technology. As a result, it is difficult in cross-sectional studies such as this one to determine whether the differences between the groups (e.g., in terms of the relative roles of environment and genetics) are due to age or to other factors

Carlson, E. A., Sroufe, L. A., & Egeland, B. (2004). The construction of experience: A longitudinal study of representation and behavior. Child Development, 75(1), 66–83.

Cassidy, J. E., & Shaver, P. R. E. (1999). Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Doherty, M. J. (2009). Theory of mind: How children understand others’ thoughts and feelings. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Jang, K. L., Livesley, W. A., & Vernon, P. A. (1996). The genetic basis of personality at different ages: A cross-sectional twin study. Personality and Individual Differences, 21, 299–301.

Jang, K. L., Livesley, W. A., & Vernon, P. A. (1996). The genetic basis of personality at different ages: A cross-sectional twin study. Personality and Individual Differences, 21, 299–301

Lucas-Thompson, R., & Clarke-Stewart, K. A. (2007). Forecasting friendship: How marital quality, maternal mood, and attachment security are linked to children’s peer relationships. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 28(5–6), 499–514.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Waters, E., Merrick, S., Treboux, D., Crowell, J., & Albersheim, L. (2000). Attachment security in infancy and early adulthood: A twenty-year longitudinal study. Child Development, 71(3), 684–689.

Attachment Theory-Video

Counselling Tutor. (2012, May 19). 1-3: Attachment Theory (Part 2 John Bowlby-Mary Ainsworth) [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xot1B5E5oOo. Standard YouTube license.

Summary

Social development requires the development of a secure base from which children feel free to explore. Attachment styles refer to the security of this base and more generally to the type of relationship that people, and especially children, develop with those who are important to them. Longitudinal and cross-sectional studies are used to test hypotheses about development, and each approach has advantages and disadvantages.

An important part of development is the attainment of social skills, including the formation of the self-concept and attachment. John Bowlby coined the term attachment theory which is a model that seeks to capture the emotional bonds that connects one person to another, across time and space. Attachment theory originated with the work of John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth expanded upon his work and through her research in the 1970s coined the term “strange situation.” This refers to the observations of children between the ages of nine and 18 months and the child’s reaction to the primary caregivers being visibly present. From this study, Ainsworth classified the attachment styles of the children into three attachment styles; secure, resistant and avoidant. Later, a fourth attachment style was identified. Ainsworth’s findings provided the first empirical evidence in support of John Bowlby’s attachment theory.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.