Psychological Disorders

Introduction

The focus of this section is on abnormal psychology—the application of psychological science to understanding and treating mental disorders. This is an important area to cover because more psychologists are involved in the diagnosis and treatment of psychological disorders than in any other endeavor, and these are probably the most important tasks psychologists face. About 1 in every 4 Americans (or over 60 million people) are affected by a psychological disorder during any one year (Kessler, Chiu, Demler, & Walters, 2005), and at least a half billion people are affected worldwide.

The impact of mental illness is particularly strong on people who are of lower socioeconomic class and from disadvantaged ethnic groups (Hatzenbuehler, Phelan, & Link, 2013). People with psychological disorders are also stigmatized by the people around them, resulting in shame and embarrassment, as well as prejudice and discrimination against them (Schmitt, Branscombe, Postmes, & Garcia, 2014). Thus, the understanding and treatment of psychological disorders has broad implications for the everyday life of many people.

In this section our focus is on the disorders themselves. We will review the major psychological disorders and consider their causes and their impact on the people who suffer from them. In later sections we will turn to consider the treatment of these disorders through various treatment modalities.

Butcher, J., Mineka, S., & Hooley, J. (2007). Abnormal psychology and modern life (13th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Phelan, J. C., & Link, B. G. (2013). Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. American Journal of Public Health, 103(5), 813–821.

Kessler, R. C., Chiu, W. T., Demler, O., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 617–627.

Mitchell, N. (Producer). (2002, April 28). Body dysmorphic disorder and cosmetic “surgery of the psyche.” All in the mind. ABC Radio National. Retrieved from http://www.abc.net.au/rn/allinthemind/stories/2003/746058.htm

Schmitt, M. T., Branscombe, N. R., Postmes, T., & Garcia, A. (2014). The consequences of perceived discrimination for psychological well-being: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 140(4), 921.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Psychological Disorders

The Bio-Psycho-Social Model

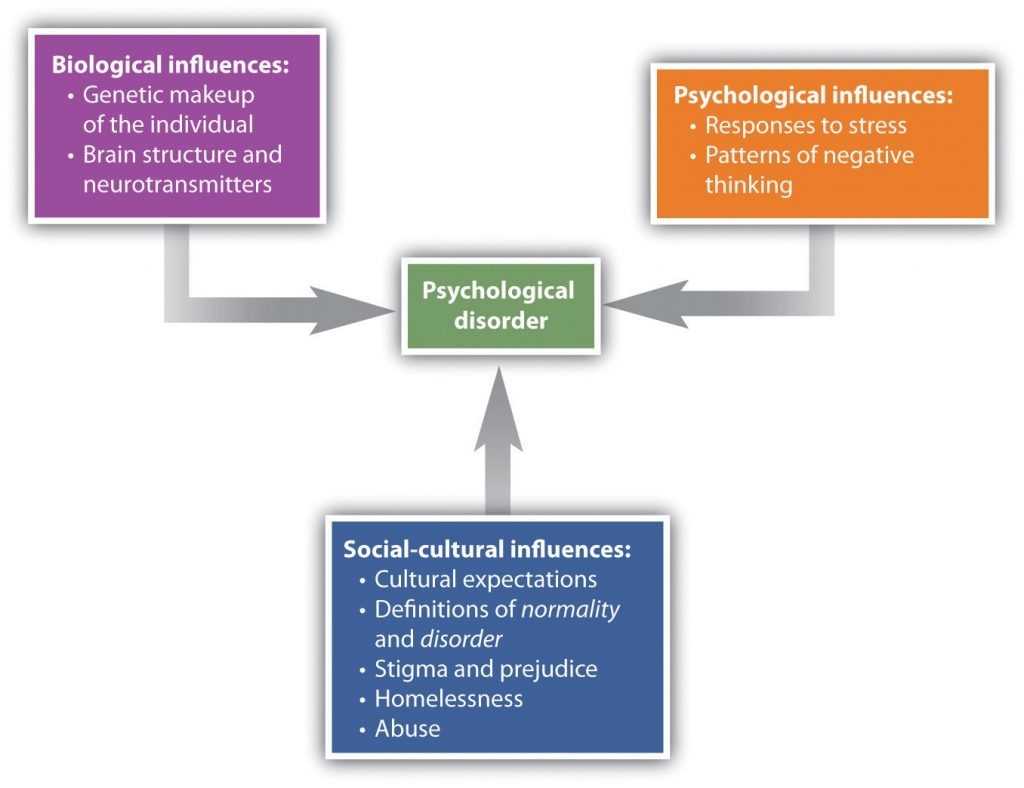

A psychological disorder is an ongoing dysfunctional pattern of thought, emotion, and behavior that causes significant distress, and that is considered deviant in that person’s culture or society (Butcher, Mineka, & Hooley, 2007). Psychological disorders have much in common with other medical disorders; they are out of the patient’s control, they can sometimes be treated by drugs, and their treatment is often covered by medical insurance. Like medical problems, psychological disorders have both biological (nature) as well as environmental (nurture) influences. These causal influences are reflected in the bio-psycho-social model of illness (Engel, 1977). The bio-psycho-social model of illness is a way of understanding disorder that assumes that disorder is caused by biological, psychological, and social factors. The biological component of the bio-psycho-social model refers to the influences on disorder that come from the functioning of the individual’s body. Particularly important are genetic characteristics that make some people more vulnerable to a disorder than others, as well as the influence of neurotransmitters (Charney, Nestler, Sklar, & Buxbaum, 2013). The psychological component of the bio-psycho-social model refers to the influences that come from the individual, such as patterns of negative thinking and stress responses. The social component of the bio-psycho-social model refers to the influences on disorder due to social and cultural factors such as socioeconomic status, homelessness, abuse, and discrimination.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Butcher, J., Mineka, S., & Hooley, J. (2007). Abnormal psychology and modern life (13th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Charney, D. S., Nestler, E. J., Sklar, P., & Buxbaum, J. D. (2013). Neurobiology of Mental Illness. Oxford University Press.

Engel, G. (1977). The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science, 196(4286), 129. doi:10.1126/science.847460.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

What are Psychological Disorders?

A psychological disorder is a condition characterized by abnormal thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Psychopathology is the study of psychological disorders, including their symptoms, etiology (i.e., their causes), and treatment. The term psychopathology can also refer to the manifestation of a psychological disorder. Although consensus can be difficult, it is extremely important for mental health professionals to agree on what kinds of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are truly abnormal in the sense that they genuinely indicate the presence of psychopathology. Certain patterns of behavior and inner experience can easily be labeled as abnormal and clearly signify some kind of psychological disturbance.

The person who washes his hands 40 times per day and the person who claims to hear the voices of demons exhibit behaviors and inner experiences that most would regard as abnormal: beliefs and behaviors that suggest the existence of a psychological disorder. But, consider the nervousness a young man feels when talking to attractive women or the loneliness and longing for home a freshman experiences during her first semester of college—these feelings may not be regularly present, but they fall in the range of normal. So, what kinds of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors represent a true psychological disorder? Psychologists work to distinguish psychological disorders from inner experiences and behaviors that are merely situational, idiosyncratic, or unconventional.

Definition of a Psychological Disorder

Perhaps the simplest approach to conceptualizing psychological disorders is to label behaviors, thoughts, and inner experiences that are atypical, distressful, dysfunctional, and sometimes even dangerous, as signs of a disorder. For example, if you ask a classmate for a date and you are rejected, you probably would feel a little dejected. Such feelings would be normal. If you felt extremely depressed—so much so that you lost interest in activities, had difficulty eating or sleeping, felt utterly worthless, and contemplated suicide—your feelings would be atypical, would deviate from the norm, and could signify the presence of a psychological disorder. Just because something is atypical, however, does not necessarily mean it is disordered.

For example, only about 4% of people in the United States have red hair, so red hair is considered an atypical characteristic, but it is not considered disordered, it’s just unusual. And it is less unusual in Scotland, where approximately 13% of the population has red hair (“DNA Project Aims,” 2012). As you will learn, some disorders, although not exactly typical, are far from atypical, and the rates in which they appear in the population are surprisingly high.

If we can agree that merely being atypical is an insufficient criterion for a having a psychological disorder, is it reasonable to consider behavior or inner experiences that differ from widely expected cultural values or expectations as disordered? Using this criterion, a woman who walks around a subway platform wearing a heavy winter coat in July while screaming obscenities at strangers may be considered as exhibiting symptoms of a psychological disorder. Her actions and clothes violate socially accepted rules governing appropriate dress and behavior; these characteristics are atypical.

Cultural Expectations

Violating cultural expectations is not, in and of itself, a satisfactory means of identifying the presence of a psychological disorder. Since behavior varies from one culture to another, what may be expected and considered appropriate in one culture may not be viewed as such in other cultures. For example, returning a stranger’s smile is expected in the United States because a pervasive social norm dictates that we reciprocate friendly gestures. A person who refuses to acknowledge such gestures might be considered socially awkward—perhaps even disordered—for violating this expectation.

However, such expectations are not universally shared. Cultural expectations in Japan involve showing reserve, restraint, and a concern for maintaining privacy around strangers. Japanese people are generally unresponsive to smiles from strangers (Patterson et al., 2007). Eye contact provides another example. In the United States and Europe, eye contact with others typically signifies honesty and attention. However, most Latin-American, Asian, and African cultures interpret direct eye contact as rude, confrontational, and aggressive (Pazain, 2010). Thus, someone who makes eye contact with you could be considered appropriate and respectful or brazen and offensive, depending on your culture.

Hallucinations (seeing or hearing things that are not physically present) in Western societies is a violation of cultural expectations, and a person who reports such inner experiences is readily labeled as psychologically disordered. In other cultures, visions that, for example, pertain to future events may be regarded as normal experiences that are positively valued (Bourguignon, 1970). Finally, it is important to recognize that cultural norms change over time: what might be considered typical in a society at one time may no longer be viewed this way later, similar to how fashion trends from one era may elicit quizzical looks decades later—imagine how a headband, legwarmers, and the big hair of the 1980s would go over on your campus today.

Harmful Dysfunction

If none of the criteria discussed so far is adequate by itself to define the presence of a psychological disorder, how can a disorder be conceptualized? Many efforts have been made to identify the specific dimensions of psychological disorders, yet none is entirely satisfactory. No universal definition of psychological disorder exists that can apply to all situations in which a disorder is thought to be present (Zachar & Kendler, 2007). However, one of the more influential conceptualizations was proposed by Wakefield (1992), who defined psychological disorder as a harmful dysfunction.

Wakefield argued that natural internal mechanisms—that is, psychological processes honed by evolution, such as cognition, perception, and learning—have important functions, such as enabling us to experience the world the way others do and to engage in rational thought, problem solving, and communication. For example, learning allows us to associate a fear with a potential danger in such a way that the intensity of fear is roughly equal to the degree of actual danger. Dysfunction occurs when an internal mechanism breaks down and can no longer perform its normal function. But, the presence of a dysfunction by itself does not determine a disorder. The dysfunction must be harmful in that it leads to negative consequences for the individual or for others, as judged by the standards of the individual’s culture. The harm may include significant internal anguish (e.g., high levels of anxiety or depression) or problems in day-to-day living (e.g., in one’s social or work life).

To illustrate, Janet has an extreme fear of spiders. Janet’s fear might be considered a dysfunction in that it signals that the internal mechanism of learning is not working correctly (i.e., a faulty process prevents Janet from appropriately associating the magnitude of her fear with the actual threat posed by spiders). Janet’s fear of spiders has a significant negative influence on her life: she avoids all situations in which she suspects spiders to be present (e.g., the basement or a friend’s home), and she quit her job last month because she saw a spider in the restroom at work and is now unemployed.

According to the harmful dysfunction model, Janet’s condition would signify a disorder because (a) there is a dysfunction in an internal mechanism, and (b) the dysfunction has resulted in harmful consequences. Similar to how the symptoms of physical illness reflect dysfunctions in biological processes, the symptoms of psychological disorders presumably reflect dysfunctions in mental processes. The internal mechanism component of this model is especially appealing because it implies that disorders may occur through a breakdown of biological functions that govern various psychological processes, thus supporting contemporary neurobiological models of psychological disorders (Fabrega, 2007).

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) Definition

Many of the features of the harmful dysfunction model are incorporated in a formal definition of psychological disorder developed by the American Psychiatric Association (APA).

According to the APA (2013), a psychological disorder is a condition that is said to consist of the following:

- There are significant disturbances in thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. A person must experience inner states (e.g., thoughts and/or feelings) and exhibit behaviors that are clearly disturbed—that is, unusual, but in a negative, self-defeating way. Often, such disturbances are troubling to those around the individual who experiences them. For example, an individual who is uncontrollably preoccupied by thoughts of germs spends hours each day bathing, has inner experiences, and displays behaviors that most would consider atypical and negative (disturbed) and that would likely be troubling to family members.

- The disturbances reflect some kind of biological, psychological, or developmental dysfunction. Disturbed patterns of inner experiences and behaviors should reflect some flaw (dysfunction) in the internal biological, psychological, and developmental mechanisms that lead to normal, healthy psychological functioning. For example, the hallucinations observed in schizophrenia could be a sign of brain abnormalities.

- The disturbances lead to significant distress or disability in one’s life. A person’s inner experiences and behaviors are considered to reflect a psychological disorder if they cause the person considerable distress, or greatly impair his ability to function as a normal individual (often referred to as functional impairment, or occupational and social impairment). As an illustration, a person’s fear of social situations might be so distressing that it causes the person to avoid all social situations (e.g., preventing that person from being able to attend class or apply for a job).

- The disturbances do not reflect expected or culturally approved responses to certain events. Disturbances in thoughts, feelings, and behaviors must be socially unacceptable responses to certain events that often happen in life. For example, it is perfectly natural (and expected) that a person would experience great sadness and might wish to be left alone following the death of a close family member. Because such reactions are in some ways culturally expected, the individual would not be assumed to signify a mental disorder.

Some believe that there is no essential criterion or set of criteria that can definitively distinguish all cases of disorder from nondisorder (Lilienfeld & Marino, 1999). In truth, no single approach to defining a psychological disorder is adequate by itself, nor is there universal agreement on where the boundary is between disordered and not disordered. From time to time we all experience anxiety, unwanted thoughts, and moments of sadness; our behavior at other times may not make much sense to ourselves or to others. These inner experiences and behaviors can vary in their intensity, but are only considered disordered when they are highly disturbing to us and/or others, suggest a dysfunction in normal mental functioning, and are associated with significant distress or disability in social or occupational activities.

“Psychology: Chapter 15: Psychological Disorders” by OpenStax. Retrieved from https://learn.saylor.org/pluginfile.php/40708/mod_resource/content/1/OpenStax-Psychology.pdf. Licensed under CC BY.

Diagnosing and Classifying Psychological Disorders

A first step in the study of psychological disorders is carefully and systematically discerning significant signs and symptoms. How do mental health professionals ascertain whether or not a person’s inner states and behaviors truly represent a psychological disorder? Arriving at a proper diagnosis—that is, appropriately identifying and labeling a set of defined symptoms—is absolutely crucial. This process enables professionals to use a common language with others in the field and aids in communication about the disorder with the patient, colleagues and the public. A proper diagnosis is an essential element to guide proper and successful treatment. For these reasons, classification systems that organize psychological disorders systematically are necessary.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)

Although a number of classification systems have been developed over time, the one that is used by most mental health professionals in the United States is the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), published by the American Psychiatric Association (2013). (Note that the American Psychiatric Association differs from the American Psychological Association; both are abbreviated APA.) The first edition of the DSM, published in 1952, classified psychological disorders according to a format developed by the U.S. Army during World War II (Clegg, 2012). In the years since, the DSM has undergone numerous revisions and editions.

The most recent edition, published in 2013, is the DSM-5 (APA, 2013). The DSM-5 includes many categories of disorders (e.g., anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, and dissociative disorders). Each disorder is described in detail, including an overview of the disorder (diagnostic features), specific symptoms required for diagnosis (diagnostic criteria), prevalence information (what percent of the population is thought to be afflicted with the disorder), and risk factors associated with the disorder. The subsequent figure shows lifetime prevalence rates—the percentage of people in a population who develop a disorder in their lifetime—of various psychological disorders among U.S. adults. These data were based on a national sample of 9,282 U.S. residents (National Comorbidity Survey, 2007).

The DSM-5 also provides information about comorbidity; the co-occurrence of two disorders. For example, the DSM-5 mentions that 41% of people with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) also meet the diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder. Drug use is highly comorbid with other mental illnesses; 6 out of 10 people who have a substance use disorder also suffer from another form of mental illness (National Institute on Drug Abuse [NIDA], 2007).

“Psychology: Chapter 15: Psychological Disorders” by OpenStax. Retrieved from https://learn.saylor.org/pluginfile.php/40708/mod_resource/content/1/OpenStax-Psychology.pdf. Licensed under CC BY.

Psychological Disorders

Elizabeth Casey (2016, July 6). Abnormal Behavior-Psychology [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LE_6BljmZjU. Standard YouTube license.

CrashCourse. (2014, August 25). Psychological Disorders: Crash Course Psychology #28. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wuhJ-GkRRQc. Standard YouTube License.

Terry Bell. (2011, June 19). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (history).wmv. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hfOfy3jXuCo. Standard YouTube License.

Summary

Psychological disorders are conditions characterized by abnormal thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Although challenging, it is essential for psychologists and mental health professionals to agree on what kinds of inner experiences and behaviors constitute the presence of a psychological disorder. Inner experiences and behaviors that are atypical or violate social norms could signify the presence of a disorder; however, each of these criteria alone is inadequate.

Harmful dysfunction describes the view that psychological disorders result from the inability of an internal mechanism to perform its natural function. Many of the features of harmful dysfunction conceptualization have been incorporated in the APA’s formal definition of psychological disorders. According to this definition, the presence of a psychological disorder is signaled by significant disturbances in thoughts, feelings, and behaviors; these disturbances must reflect some kind of dysfunction (biological, psychological, or developmental), must cause significant impairment in one’s life, and must not reflect culturally expected reactions to certain life events.

The diagnosis and classification of psychological disorders is essential in studying and treating psychopathology. The classification system used by most U.S. professionals is the DSM-5. The first edition of the DSM was published in 1952, and has undergone numerous revisions. The 5th and most recent edition, the DSM-5, was published in 2013. The diagnostic manual includes a total of 237 specific diagnosable disorders, each described in detail, including its symptoms, prevalence, risk factors, and comorbidity. Over time, the number of diagnosable conditions listed in the DSM has grown steadily, prompting criticism from some. Nevertheless, the diagnostic criteria in the DSM are more explicit than that of any other system, which makes the DSM system highly desirable for both clinical diagnosis and research.

Psychopathology is very complex, involving a plethora of etiological theories and perspectives. Psychologists study psychological disorders by considering biological, psychological, and social influences, known as the bio-psycho-social model.

“Psychology: Chapter 15: Psychological Disorders” by OpenStax. Retrieved from https://learn.saylor.org/pluginfile.php/40708/mod_resource/content/1/OpenStax-Psychology.pdf. Licensed under CC BY.