Mood and Personality Disorders

Introduction

The everyday variations in our feelings of happiness and sadness reflect our mood, which can be defined as the positive or negative feelings that are in the background of our everyday experiences. In most cases, we are in a relatively good mood, and this positive mood has some positive consequences: it encourages us to do what needs to be done and to make the most of the situations we are in (Isen, 2003). When we are in a good mood, our thought processes open up and we are more likely to approach others. We are more friendly and helpful to others when we are in a good mood than we are when we are in a bad mood, and we may think more creatively (De Dreu, Baas, & Nijstad, 2008). On the other hand, when we are in a bad mood, we are more likely to prefer to be alone rather than interact with others, we focus on the negative things around us, and our creativity suffers.

In addition to covering mood disorders, this section will also review personality disorders. A personality disorder is a condition characterized by inflexible patterns of thinking, feeling, or relating to others that cause problems in personal, social, and work situations. As you consider the different personality types, I’m sure you’ll think of people that you know who have each of these characteristics, at least to some degree. Probably you know someone who seems a bit suspicious and paranoid, who feels that other people are always “ganging up on him,” and who really doesn’t trust other people very much. Perhaps you know someone who fits the bill of being overly dramatic—the “drama queen” who is always raising a stir and whose emotions seem to turn everything into a big deal. Or you might have a friend who is overly dependent on others and can’t seem to get a life of her own. The personality traits that make up the personality disorders are common—we see them in the people whom we interact with every day—yet they may become problematic when they are rigid, overused, or interfere with everyday behavior (Lynam & Widiger, 2001). What is perhaps common to all the disorders is the person’s inability to accurately understand and be sensitive to the motives and needs of the people around them.

De Dreu, C. K. W., Baas, M., & Nijstad, B. A. (2008). Hedonic tone and activation level in the mood-creativity link: Toward a dual pathway to creativity model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94(5), 739–756.

Isen, A. M. (2003). Positive affect as a source of human strength. In J. Aspinall, A psychology of human strengths: Fundamental questions and future directions for a positive psychology (pp. 179–195). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.↑

Lynam, D., & Widiger, T. (2001). Using the five-factor model to represent the DSM-IV personality disorders: An expert consensus approach. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110(3), 401–412.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Mood and Personality Disorders

Depressive Disorders: Emotions as Illness

It is not unusual to feel “down” or “low” at times, particularly after a painful event such as the death of someone close to us, a disappointment at work, or an argument with a friend or partner. We often get depressed when we are tired, and many people report being particularly sad during the winter when the days are shorter. Mood (or affective) disorders are psychological disorders in which the person’s mood negatively influences his or her physical, perceptual, social, and cognitive processes. People who suffer from depressive disorders tend to experience more intense—and particularly more intense negative—moods. About 10% of the U.S. population suffers from a depressive disorder in a given year, but it has also been argued that depression is over-diagnosed by psychologists and psychiatrists (Horwitz & Wakefield, 2007). Feeling sad some days may not really be a psychological disorder. The most common symptom of depressive disorders is negative mood, also known as sadness or depression. Consider the feelings of this person, who was struggling with depression and was diagnosed with major depressive disorder:

I didn’t want to face anyone; I didn’t want to talk to anyone. I didn’t really want to do anything for myself . . . I couldn’t sit down for a minute really to do anything that took deep concentration . . . It was like I had big huge weights on my legs and I was trying to swim and just kept sinking. And I’d get a little bit of air, just enough to survive and then I’d go back down again. It was just constantly, constantly just fighting, fighting, fighting, fighting, fighting (National Institute of Mental Health, 2010).

Depressive disorders can occur at any age, and the median age of onset is 32 years (Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin, & Walters, 2005). Recurrence of depressive episodes is fairly common and is greatest for those who first experience depression before the age of 15 years. About twice as many women as men suffer from depression (Culbertson, 1997). This gender difference is consistent across many countries and cannot be explained entirely by the fact that women are more likely to seek treatment for their depression. Rates of depression have been increasing over the past years, although the reasons for this increase are not known (Kessler et al., 2003).

The experience of depression has a variety of negative effects on our behaviors. In addition to the loss of interest, productivity, and social contact that accompanies depression, the person’s sense of hopelessness and sadness may become so severe that he or she considers or even succeeds in committing suicide. Suicide is the 11th leading cause of death in the United States, and a suicide occurs approximately every 16 minutes. Almost all the people who commit suicide have a diagnosable psychiatric disorder at the time of their death (American Association of Suicidology, 2010; Sudak, 2005).

Behaviors Associated with Depression:

- Changes in appetite; weight loss or gain

- Difficult concentrating, remember details, and making decisions

- Fatigue and decreased energy

- Feelings of hopelessness, helplessness, and pessimism

- Increased use of alcohol or drugs

- Irritability, restlessness

- Loss of interest in activities or hobbies once pleasurable, including sex

- Loss of interest in personal appearance

- Persistent aches or pains, headaches, cramps, or digestive problems that do not improve the treatment

- Sleep disorders, either trouble sleeping or excessive sleeping

- Thoughts or attempts of suicide

Dysthymia and Major Depressive Disorder

The level of depression observed in people with depressive disorders varies widely. People who experience depression for many years, such that it starts to seem normal and a part of everyday life, and who feel that they are rarely or never happy, will likely be diagnosed with a depressive disorder. If the depression is mild but long-lasting, they will be diagnosed with persistent depressive disorder (PDD), a condition characterized by mild, but chronic, depressive symptoms that last for at least 2 years.

If the depression continues and becomes even more severe, the diagnosis may become that of major depressive disorder. Major depressive disorder (MDD) (clinical depression) is a mental disorder characterized by an all-encompassing low mood accompanied by low self-esteem and by loss of interest or pleasure in normally enjoyable activities. Those who suffer from major depressive disorder feel an intense sadness, despair, and loss of interest in pursuits that once gave them pleasure. These negative feelings profoundly limit the individual’s day-to-day functioning and ability to maintain and develop interests in life (Fairchild & Scogin, 2008). In some cases, clinically depressed people lose contact with reality and may receive a diagnosis of major depressive episode with psychotic features. In these cases the depression includes delusions and hallucinations.

Bipolar Disorder

Juliana is a 21-year-old single woman. Over the past several years she had been treated by a psychologist for depression, but for the past few months she had been feeling a lot better. Juliana had landed a good job in a law office and found a steady boyfriend. She told her friends and parents that she had been feeling particularly good—her energy level was high and she was confident in herself and her life.

One day Juliana was feeling so good that she impulsively quit her new job and left town with her boyfriend on a road trip. But the trip didn’t turn out well because Juliana became impulsive, impatient, and easily angered. Her euphoria continued, and in one of the towns that they visited she left her boyfriend and went to a party with some strangers that she had met. She danced into the early morning and ended up having sex with several of the men.

Eventually Juliana returned home to ask for money, but when her parents found out about her recent behavior, and when she acted aggressively and abusively towards them when they confronted her about it, they referred her to a social worker. Juliana was hospitalized, where she was diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

While PDD and major depressive disorder are characterized by overwhelming negative moods, bipolar disorder is a psychological disorder characterized by swings in mood—from overly “high” to sad and hopeless and back again—with periods of near-normal mood in between. Although bipolar disorder is given its own category in DSM-5, it is discussed here because it has some characteristics in common with the other depressive disorders. Bipolar disorder is diagnosed in cases such as Juliana’s, where experiences with depression are followed by a more normal period and then a period of mania or euphoria in which the person feels particularly awake, alive, excited, and involved in everyday activities but is also impulsive, agitated, and distracted. Without treatment, it is likely that Juliana would cycle back into depression and then eventually into mania again, with the likelihood that she would harm herself or others in the process.

Bipolar disorder is an often chronic and lifelong condition that may begin in childhood. Although the normal pattern involves swings from high to low, in some cases the person may experience both highs and lows at the same time. Determining whether a person has bipolar disorder is difficult due to the frequent presence of comorbidity with both depression and anxiety disorders. Bipolar disorder is more likely to be diagnosed when it is initially observed at an early age, when the frequency of depressive episodes is high, and when there is a sudden onset of the symptoms (Bowden, 2001).

Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Starry_Night#/media/File:Van_Gogh_-_Starry_Night_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg. Licensed under CC0.

American Association of Suicidology. (2010, June 29). Some facts about suicide and depression. Retrieved from http://www.suicidology.org/c/document_library/get_file?folderId=232&name=DLFE-246.pdf; Sudak, H. S. (2005). Suicide. In B. J. Sadock & V. A. Sadock (Eds.), Kaplan & Sadock’s comprehensive textbook of psychiatry. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Bowden, C. L. (2001). Strategies to reduce misdiagnosis of bipolar depression. Psychiatric Services, 52(1), 51–55.

Fairchild, K., & Scogin, F. (2008). Assessment and treatment of depression. In K. Laidlow & B. Knight (Eds.), Handbook of emotional disorders in later life: Assessment and treatment. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Horwitz, A. V., & Wakefield, J. C. (2007) The Loss of Sadness: How Psychiatry Transformed Normal Sorrow into Depressive Disorder. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P. A., Demler, O., Jin, R., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IVdisorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 593–602.

Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P., Demler, O, Jin, R., Koretz, D., Merikangas, K. R.,…Wang, P. S. (2003). The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Journal of the American Medical Association, 289(23), 3095–3105.

Kessler, R. C., Chiu, W. T., Demler, O., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 617–27; Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P., Demler, O, Jin, R., Koretz, D., Merikangas, K. R.,…Wang, P. S. (2003). The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Journal of the American Medical Association, 289(23), 3095–3105.

National Institute of Mental Health. (2010, April 8). People with depression discuss their illness. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mlNCavst2EU.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Explaining Depressive Disorders

Depressive disorders are known to have some genetic component because they are heritable (Berrettini, 2006; Merikangas et al., 2002), and our understanding of diagnostic categories is being challenged by new discoveries in behavioral genetics. For instance, Hickie (2014) has reported that depression and mania are differentially heritable, suggesting that bipolar disorder may not be a single psychological problem.

Neurotransmitters also play an important role in depressive disorders. Serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine are all known to influence mood (Sher & Mann, 2003), and drugs that influence the actions of these chemicals are often used to treat depressive disorders.

The brains of those with depressive disorders may, in some cases, show structural differences from those without them. Videbech and Ravnkilde (2004) found that the hippocampus was smaller in depressed subjects than in normal subjects, and this may be the result of reduced neurogenesis (the process of generating new neurons) in depressed people (Warner-Schmidt & Duman, 2006). Antidepressant drugs may alleviate depression by increasing neurogenesis (Duman & Monteggia, 2006).

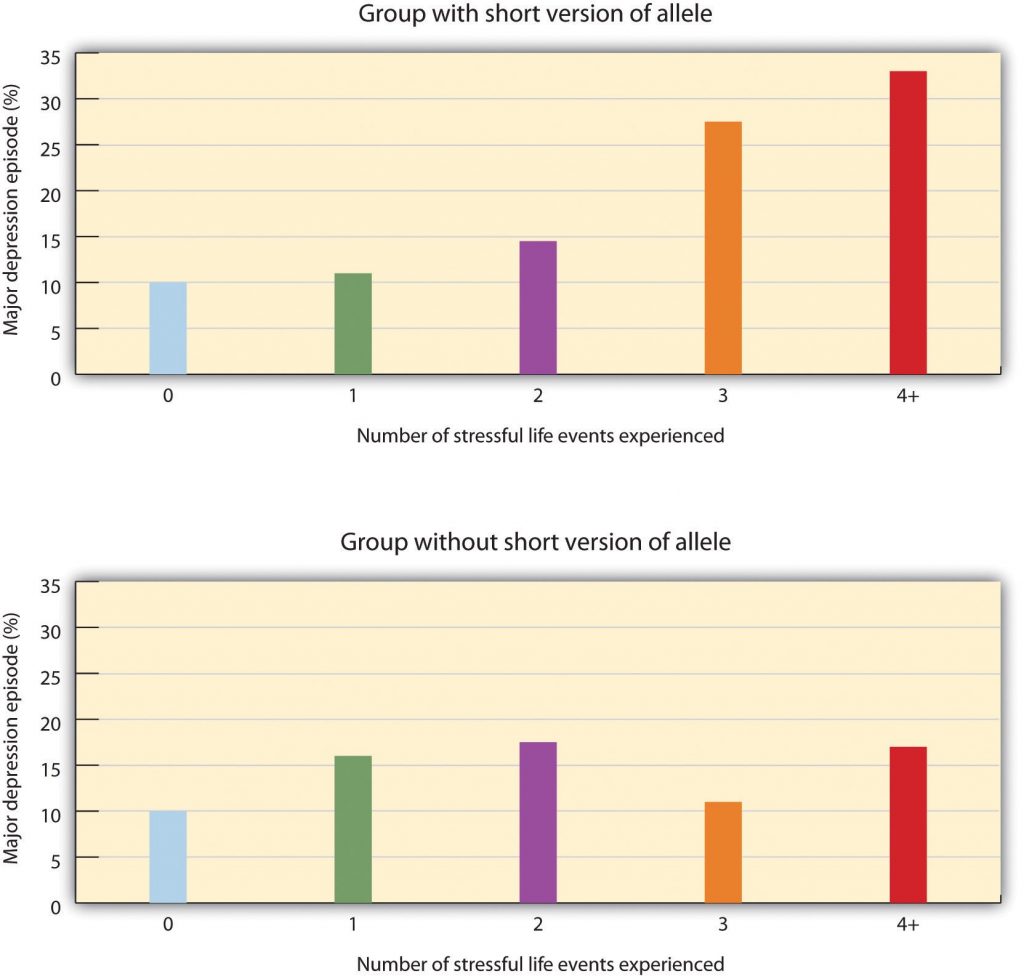

Avshalom Caspi and his colleagues (Caspi et al., 2003) used a longitudinal study to test whether genetic predispositions might lead some people, but not others, to suffer from depression as a result of environmental stress. Their research focused on a particular gene, the 5-HTT gene, which is known to be important in the production and use of the neurotransmitter serotonin. The researchers focused on this gene because serotonin is known to be important in depression, and because selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have been shown to be effective in treating depression.

People who experience stressful life events, for instance, involving threat loss, humiliation, or defeat, are likely to experience depression. But biological-situational models suggest that a person’s sensitivity to stressful events depends on his or her genetic makeup. The researchers therefore expected that people with one type of genetic pattern would show depression following stress to a greater extent than people with a different type of genetic pattern.

The research included a sample of 1,037 adults from Dunedin, New Zealand. Genetic analysis on the basis of DNA samples allowed the researchers to divide the sample into two groups on the basis of the characteristics of their 5-HTT gene. One group had a short version (or allele) of the gene, whereas the other group did not have the short allele of the gene.

The participants also completed a measure where they indicated the number and severity of stressful life events that they had experienced over the past 5 years. The events included employment, financial, housing, health, and relationship stressors. The dependent measure in the study was the level of depression reported by the participant, as assessed using a structured interview test (Robins, Cottler, Bucholtz, & Compton, 1995).

As the number of stressful experiences the participants reported increased from 0 to 4, depression also significantly increased for the participants with the short version of the gene. But for the participants who did not have a short allele, increasing stress did not increase depression. Furthermore, for the participants who experienced 4 stressors over the past 5 years, 33% of the participants who carried the short version of the gene became depressed, whereas only 17% of participants who did not have the short version did.

Source: Adapted from Caspi, A., Sugden, K., Moffitt, T. E., Taylor, A., Craig, I. W., Harrington, H.,…Poulton, R. (2003). Influence of life stress on depression: Moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science, 301(5631), 386–389.Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

This important study provides an excellent example of how genes and environment work together: An individual’s response to environmental stress was influenced by his or her genetic makeup.

But psychological and social determinants are also important in creating depressive disorders. In terms of psychological characteristics, mood states are influenced by our cognitions. Negative thoughts about ourselves and our relationships to others create negative moods, and a goal of cognitive therapy for depressive disorders is to attempt to change people’s cognitions to be more positive. Negative moods also create negative behaviors toward others, such as acting sad, slouching, and avoiding others, which may lead those others to respond negatively to the person—for instance, by isolating that person, which then creates even more depression. You can see how it might become difficult for people to break out of this “cycle of depression.”

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Weissman et al. (1996) found that rates of depression varied greatly among countries, with the highest rates in European and American countries and the lowest rates in Asian countries. These differences seem to be due to discrepancies between individual feelings and cultural expectations about what one should feel. People from European and American cultures report that it is important to experience emotions such as happiness and excitement, whereas the Chinese report that it is more important to be stable and calm. Because Americans may feel that they are not happy or excited but that they are supposed to be, this may increase their depression (Tsai, Knutson, & Fung, 2006).

Berrettini, W. (2006). Genetics of bipolar and unipolar disorders. In D. J. Stein, D. J. Kupfer, & A. F. Schatzberg (Eds.), Textbook of mood disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; Merikangas, K., Chakravarti, A., Moldin, S., Araj, H., Blangero, J., Burmeister, M,…Takahashi, A. S. (2002). Future of genetics of mood disorders research. Biological Psychiatry, 52(6), 457–477.

Caspi, A., Sugden, K., Moffitt, T. E., Taylor, A., Craig, I. W., Harrington, H.,…Poulton, R. (2003). Influence of life stress on depression: Moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science, 301(5631), 386–389.

Duman, R. S., & Monteggia, L. M. (2006). A neurotrophic model for stress-related mood disorders. Biological Psychiatry, 59, 1116–1127.

Hickie, I. B. (2014). Evidence for separate inheritance of mania and depression challenges current concepts of bipolar mood disorder. Molecular Psychiatry, 19(2), 153–155. doi:10.1038/mp.2013.173.

Robins, L. N., Cottler, L., Bucholtz, K., & Compton, W. (1995). Diagnostic interview schedule for DSM-1V. St. Louis, MO: Washington University.

Sher, L., & Mann, J. J. (2003). Psychiatric pathophysiology: Mood disorders. In A. Tasman, J. Kay, & J. A. Lieberman (Eds.), Psychiatry. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Tsai, J. L., Knutson, B., & Fung, H. H. (2006). Cultural variation in affect valuation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90, 288–307.

Videbech, P., & Ravnkilde, B. (2004). Hippocampal volume and depression: A meta-analysis of MRI studies. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161, 1957–1966.

Warner-Schmidt, J. L., & Duman, R. S. (2006). Hippocampal neurogenesis: Opposing effects of stress and antidepressant treatment. Hippocampus, 16, 239–249.

Weissman, M. M., Bland, R. C., Canino, G. J., Greenwald, S., Hwu, H-G., Joyce, P. R.,…Yeh, E-K. (1996). Cross-national epidemiology of major depression and bipolar disorder. Journal of the American Medical Association, 276, 293–299.

Personality Disorders

A personality disorder is a condition characterized by inflexible patterns of thinking, feeling, or relating to others that cause problems in personal, social, and work situations. Personality disorders tend to emerge during late childhood or adolescence and usually continue throughout adulthood (Widiger, 2006). The disorders can be problematic for the people who have them, but they are less likely to bring people to a therapist for treatment than are anxiety, mood, or other disorders.

The personality disorders create a bit of a problem for diagnosis. For one, it is frequently difficult for the clinician to accurately diagnose which of the many personality disorders a person has, although the friends and colleagues of the person can generally do a good job of it (Oltmanns & Turkheimer, 2006). And the personality disorders are highly comorbid; if a person has one, it’s likely that he or she has others as well. Also, the number of people with personality disorders is estimated to be as high as 15% of the population (Grant et al., 2004), which might make us wonder if these are really “disorders” in any real sense of the word.

Although they are considered as separate disorders, the personality disorders are essentially milder versions of some of the more severe disorders (Huang et al., 2009). For example, obsessive-compulsive personality disorder is a milder version of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and schizoid and schizotypal personality disorders are characterized by symptoms similar to those of schizophrenia. This overlap in classification causes some confusion, and some theorists have argued that the personality disorders should be eliminated from the DSM. But because clinicians normally differentiate personality disorders from other types of disorders, the distinction between them is useful (Krueger, 2005; Phillips, Yen, & Gunderson, 2003; Verheul, 2005).

Although it is not possible to consider the characteristics of each of the personality disorders in this section, let’s focus on two that have important implications for behavior. The first, borderline personality disorder (BPD), is important because it is so often associated with suicide, and the second, antisocial personality disorder (APD), because it is the foundation of criminal behavior. Borderline and antisocial personality disorders are also good examples to consider because they are so clearly differentiated in terms of their focus. BPD (more frequently found in women than men) is known as an internalizing disorder because the behaviors that it entails (e.g., suicide and self-mutilation) are mostly directed toward the self. APD (mostly found in men), on the other hand, is a type of externalizing disorder in which the problem behaviors (e.g., lying, fighting, vandalism, and other criminal activity) focus primarily on harm to others.

| Cluster | Personality Disorder | Characteristics |

| A. Odd/Eccentric | Schizotypal | Peculiar or eccentric manners of speaking or dressing. Strange beliefs. “Magical thinking” such as belief in ESP or telepathy. Difficulty forming relationships. May react oddly in conversation, not respond, or talk to self. Speech elaborate or difficult to follow. (Possibly a mild form of schizophrenia.) |

| Paranoid | Distrust in others, suspicion that people have sinister motives. Apt to challenge the loyalties of friends and read hostile intentions into others’ actions. Prone to anger and aggressive outbursts but otherwise emotionally cold. Often jealous, guarded, secretive, overly serious. | |

| Schizoid | Extreme introversion and withdrawal from relationships. Prefers to be alone, little interest in others. Humorless, distant, often absorbed with own thoughts and feelings, a daydreamer. Fearful of closeness, with poor social skills, often seen as a “loner.” | |

| B. Dramatic/Erratic | Antisocial | Impoverished moral sense or “conscience.” History of deception, crime, legal problems, impulsive and aggressive or violent behavior. Little emotional empathy or remorse for hurting others. Manipulative, careless, callous. At high risk for substance abuse and alcoholism. |

| Borderline | Unstable moods and intense, stormy personal relationships. Frequent mood changes and anger, unpredictable impulses. Self-mutilation or suicidal threats or gestures to get attention or manipulate others. Self-image fluctuation and a tendency to see others as “all good” or “all bad.” | |

| Histrionic | Constant attention seeking. Grandiose language, provocative dress, exaggerated illnesses, all to gain attention. Believes that everyone loves him. Emotional, lively, overly dramatic, enthusiastic, and excessively flirtatious. | |

| Narcissistic | Inflated sense of self-importance, absorbed by fantasies of self and success. Exaggerates own achievement, assumes others will recognize they are superior. Good first impressions but poor longer-term relationships. Exploitative of others. | |

| C. Anxious/Inhibited | Avoidant | Socially anxious and uncomfortable unless he or she is confident of being liked. In contrast with schizoid person, yearns for social contact. Fears criticism and worries about being embarrassed in front of others. Avoids social situations due to fear of rejection. |

| Dependent | Submissive, dependent, requiring excessive approval, reassurance, and advice. Clings to people and fears losing them. Lacking self-confidence. Uncomfortable when alone. May be devastated by end of close relationship or suicidal if breakup is threatened. | |

| Obsessive-Compulsive | Conscientious, orderly, perfectionist. Excessive need to do everything “right.” Inflexibly high standards and caution can interfere with his or her productivity. Fear of errors can make this person strict and controlling. Poor expression of emotions. (Not the same as obsessive-compulsive disorder.) |

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Borderline Personality Disorder

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a psychological disorder characterized by a prolonged disturbance of personality accompanied by mood swings, unstable personal relationships, identity problems, threats of self-destructive behavior, fears of abandonment, and impulsivity. BPD is widely diagnosed—up to 25% of psychiatric patients are given the diagnosis, and it may occur in up to 3% of the general population (Hyman, 2002). About three quarters of diagnosed cases of BDP are women.

People with BPD fear being abandoned by others. They often show a clinging dependency on the other person and engage in manipulation to try to maintain the relationship. They become angry if the other person limits the relationship but also deny that they care about the person. As a defense against fear of abandonment, borderline people are compulsively social, but their intense anger, demands, and suspiciousness, often repel other people.

People with BPD often deal with stress by engaging in self-destructive behaviors, for instance by being sexually promiscuous, getting into fights, binge eating and purging, engaging in self-mutilation or drug abuse, and threatening suicide. These behaviors are designed to call forth a “saving” response from the other person. People with BPD are a continuing burden for police, hospitals, and therapists. Borderline individuals also show disturbance in their concepts of identity: They are uncertain about self-image, gender identity, values, loyalties, and goals. They may have chronic feelings of emptiness or boredom and be unable to tolerate being alone.

BPD has both genetic as well as environmental roots. In terms of genetics, research has found that those with BPD frequently have neurotransmitter imbalances (Zweig-Frank et al., 2006), and the disorder is heritable (Minzenberg, Poole, & Vinogradov, 2008). In terms of environment, many theories about the causes of BPD focus on a disturbed early relationships between the child and his or her parents. Some theories focus on the development of attachment in early childhood, while others point to parents who fail to provide adequate attention to the child’s feelings. Others focus on parental abuse (both sexual and physical) in adolescence, as well as on divorce, alcoholism, and other stressors (Lobbestael & Arntz, 2009). The dangers of BPD are greater when they are associated with childhood sexual abuse, early age of onset, substance abuse, and aggressive behaviors. The problems are amplified when the diagnosis is comorbid (as it often is) with other disorders, such as substance abuse disorder, major depressive disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Skodol et al., 2002).

Research Focus: Affective and Cognitive Deficits in BPD

Posner et al. (2003) hypothesized that the difficulty that individuals with BPD have in regulating their lives (e.g., in developing meaningful relationships with other people) may be due to imbalances in the fast and slow emotional pathways in the brain. Specifically, they hypothesized that the fast emotional pathway through the amygdala is too active, and the slow cognitive-emotional pathway through the prefrontal cortex is not active enough in those with BPD.

The participants in their research were 16 patients with BPD and 14 healthy comparison participants. All participants were tested in a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) machine while they performed a task that required them to read emotional and nonemotional words, and then press a button as quickly as possible whenever a word appeared in a normal font and not press the button whenever the word appeared in an italicized font. The researchers found that while all participants performed the task well, the patients with BPD had more errors than the controls (both in terms of pressing the button when they should not have and not pressing it when they should have). These errors primarily occurred on the negative emotional words. In comparison to the controls, the borderline patients showed relatively larger affective responses when they were attempting to quickly respond to the negative emotions, and showed less cognitive activity in the prefrontal cortex in the same conditions. This research suggests that excessive affective reactions and lessened cognitive reactions to emotional stimuli may contribute to the emotional and behavioral volatility of borderline patients.

Antisocial Personality Disorder (APD)

In contrast to borderline personality disorder, which involves primarily feelings of inadequacy and a fear of abandonment, antisocial personality disorder (APD) is characterized by a disregard of the rights of others, and a tendency to violate those rights without being concerned about doing so. APD is a pervasive pattern of violation of the rights of others that begins in childhood or early adolescence and continues into adulthood. APD is about three times more likely to be diagnosed in men than in women. To be diagnosed with APD the person must be 18 years of age or older and have a documented history of conduct disorder before the age of 15. People having antisocial personality disorder are sometimes referred to as “sociopaths” or “psychopaths.”

People with APD feel little distress for the pain they cause others. They lie, engage in violence against animals and people, and frequently have drug and alcohol abuse problems. They are egocentric and frequently impulsive, for instance suddenly changing jobs or relationships. People with APD soon end up with a criminal record and often spend time incarcerated. The intensity of antisocial symptoms tends to peak during the 20s and then may decrease over time.

Biological and environmental factors are both implicated in the development of antisocial personality disorder (Rhee & Waldman, 2002). Twin and adoption studies suggest a genetic predisposition (Rhee & Waldman, 2000) and biological abnormalities include low autonomic activity during stress, biochemical imbalances, right hemisphere abnormalities, and reduced gray matter in the frontal lobes (Lyons-Ruth et al., 2007; Raine, Lencz, Bihrle, LaCasse, & Colletti, 2000). Environmental factors include neglectful and abusive parenting styles, such as the use of harsh and inconsistent discipline and inappropriate modeling (Huesmann & Kirwil, 2007).

Grant, B., Hasin, D., Stinson, F., Dawson, D., Chou, S., Ruan, W., & Pickering, R. P. (2004). Prevalence, correlates, and disability of personality disorders in the United States: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 65(7), 948–958.

Huang, Y., Kotov, R., de Girolamo, G., Preti, A., Angermeyer, M., Benjet, C.,…Kessler, R. C. (2009). DSM-IV personality disorders in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. British Journal of Psychiatry, 195(1), 46–53. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.108.058552.

Huesmann, L. R., & Kirwil, L. (2007). Why observing violence increases the risk of violent behavior by the observer. In D. J. Flannery, A. T. Vazsonyi, & I. D. Waldman (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of violent behavior and aggression (pp. 545–570). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Hyman, S. E. (2002). A new beginning for research on borderline personality disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 51(12), 933–935.

Krueger, R. F. (2005). Continuity of Axes I and II: Towards a unified model of personality, personality disorders, and clinical disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders, 19, 233–261; Phillips, K. A., Yen, S., & Gunderson, J. G. (2003). Personality disorders. In R. E. Hales & S. C. Yudofsky (Eds.), Textbook of clinical psychiatry. Washington, DC:

Lobbestael, J., & Arntz, A. (2009). Emotional, cognitive and physiological correlates of abuse-related stress in borderline and antisocial personality disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(2), 116–124. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2009.09.015.

Lyons-Ruth, K., Holmes, B. M., Sasvari-Szekely, M., Ronai, Z., Nemoda, Z., & Pauls, D. (2007). Serotonin transporter polymorphism and borderline or antisocial traits among low-income young adults. Psychiatric Genetics, 17, 339–343; Raine, A., Lencz, T., Bihrle, S., LaCasse, L., & Colletti, P. (2000). Reduced prefrontal gray matter volume and reduced autonomic activity in antisocial personality disorder. Archive of General Psychiatry, 57, 119–127.

Minzenberg, M. J., Poole, J. H., & Vinogradov, S. (2008). A neurocognitive model of borderline personality disorder: Effects of childhood sexual abuse and relationship to adult social attachment disturbance. Development and Psychological disorder. 20(1), 341–368. doi:10.1017/S0954579408000163.

Oltmanns, T. F., & Turkheimer, E. (2006). Perceptions of self and others regarding pathological personality traits. In R. F. Krueger & J. L. Tackett (Eds.), Personality and psychopathology (pp. 71–111). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Posner, M., Rothbart, M., Vizueta, N., Thomas, K., Levy, K., Fossella, J.,…Kernberg, O. (2003). An approach to the psychobiology of personality disorders. Development and Psychopathology, 15(4), 1093–1106. doi:10.1017/S0954579403000506.

Rhee, S. H., & Waldman, I. D. (2002). Genetic and environmental influences on anti-social behavior: A meta-analysis of twin and adoptions studies. Psychological Bulletin, 128(3), 490–529.

Skodol, A. E., Gunderson, J. G., Pfohl, B., Widiger, T. A., Livesley, W. J., & Siever, L. J. (2002). The borderline diagnosis I: Psychopathology, comorbidity, and personality structure. Biological Psychiatry, 51(12), 936–950.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Widiger, T.A. (2006). Understanding personality disorders. In S. K. Huprich (Ed.), Rorschach assessment to the personality disorders. The LEA series in personality and clinical psychology (pp. 3–25). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Zweig-Frank, H., Paris, J., Kin, N. M. N. Y., Schwartz, G., Steiger, H., & Nair, N. P. V. (2006). Childhood sexual abuse in relation to neurobiological challenge tests in patients with borderline personality disorder and normal controls. Psychiatry Research, 141(3), 337–341.

Mood and Personality Disorders-Video

CrashCourse. (2014, September 8). Depressive and bipolar disorders: Crash course psychology #30. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZwMlHkWKDwM. Standard YouTube License.

CrashCourse. (2014, October 14). Personality disorders: Crash course psychology #34. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4E1JiDFxFGk. Standard YouTube License.

Summary

In this section we explored the impact of mood disorders, such as depressive disorders and bi-polar disorders on an individual. Mood is the positive or negative feelings that are in the background of our everyday experiences. Depressive disorders are psychological disorders in which the person’s mood negatively influences his or her physical, perceptual, social, and cognitive processes. They include persistent depressive disorder and major depressive disorder. Bipolar disorders are disorders in which both negative and positive moods are experienced, often in extreme swings between them. Depressive disorders are caused by the interplay among biological, psychological, and social variables. Mood and bipolar disorders affect over 30 million Americans every year.

We also covered personality disorders, specifically focusing on the two that have important implications for behavior: borderline personality disorder and antisocial personality disorder. A personality disorder is a long-lasting but frequently less severe disorder characterized by inflexible patterns of thinking, feeling, or relating to others that causes problems in personal, social, and work situations. They are characterized by odd or eccentric behavior, by dramatic or erratic behavior, or by anxious or inhibited behavior. Two of the most important personality disorders are borderline personality disorder (BPD) and antisocial personality disorder (APD). Personality disorders tend to emerge during late childhood or adolescence, and usually continue throughout adulthood. Although they are considered as separate disorders, the personality disorders are essentially milder versions of more severe disorders.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.