Anxiety, Trauma, OCD, and DID

Introduction

In this section we will focus on anxiety and the impact of those who suffer from this illness. Anxiety, the nervousness or agitation that we sometimes experience, often about something that is going to happen, is a natural part of life. We all feel anxious at times, maybe when we think about our upcoming visit to the dentist or the presentation we have to give to our class next week. Anxiety is an important and useful human emotion; it is associated with the activation of the sympathetic nervous system and the physiological and behavioral responses that help protect us from danger. But too much anxiety can be debilitating, and every year millions of people suffer from anxiety disorders, which are psychological disturbances marked by irrational fears, often of everyday objects and situations (Kessler, Chiu, Demler, & Walters, 2005).

This section will also provide an introduction to obsessive-compulsive disorder, trauma and dissociative identity disorder. These disorders were once considered to be anxiety disorders, however; in the newest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental disorders (DSM-5), important changes were made and these illnesses were no longer considered to be anxiety disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). New chapters were created to include the following: Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, Trauma and Stressor Related Disorders, and Dissociative Disorders.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostics and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Kessler, R., Chiu, W., Demler, O., & Walters, E. (2005). Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 617–627.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

van der Hart, O., & Nijenhuis, E. R. S. (2009). Dissociative disorders. In P. H. Blaney & T. M. Millon (Eds.), Oxford textbook of psychological disorder (2nd ed., pp. 452–481). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Anxiety, Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, Trauma and Dissociative Identity Disorders

Anxiety

Consider the following, in which “Chase” describes her feelings of a persistent and exaggerated sense of anxiety, even when there is little or nothing in her life to provoke it:

For a few months now I’ve had a really bad feeling inside of me. The best way to describe it is like a really bad feeling of negative inevitability, like something really bad is impending, but I don’t know what. It’s like I’m on trial for murder or I’m just waiting to be sent down for something. I have it all of the time but it gets worse in waves that come from nowhere with no apparent triggers. I used to get it before going out for nights out with friends, and it kinda stopped me from doing it as I’d rather not go out and stress about the feeling, but now I have it all the time so it doesn’t really make a difference anymore. (Chase, 2010).

Chase is probably suffering from a generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), a psychological disorder diagnosed in situations in which a person has been excessively worrying about money, health, work, family life, or relationships for at least 6 months, even though he or she knows that the concerns are exaggerated, and when the anxiety causes significant distress and dysfunction. In addition to their feelings of anxiety, people who suffer from GAD may also experience a variety of physical symptoms, including irritability, sleep troubles, difficulty concentrating, muscle aches, trembling, perspiration, and hot flashes. The sufferer cannot deal with what is causing the anxiety, nor avoid it, because there is no clear cause for anxiety. In fact, the sufferer frequently knows, at least cognitively, that there is really nothing to worry about.

About 10 million Americans suffer from GAD, and about two thirds are women (Kessler, Chiu, Demler, & Walters, 2005; Robins & Regier, 1991). Generalized anxiety disorder is most likely to develop between the ages of 7 and 40 years, but its influence may, in some cases, lessen with age (Rubio & Lopez-Ibor, 2007).

Panic Disorder

When I was about 30 I had my first panic attack. I was driving home, my three little girls were in their car seats in the back, and all of a sudden I couldn’t breathe, I broke out into a sweat, and my heart began racing and literally beating against my ribs! I thought I was going to die. I pulled off the road and put my head on the wheel. I remember songs playing on the CD for about 15 minutes and my kids’ voices singing along. I was sure I’d never see them again. And then, it passed. I slowly got back on the road and drove home. I had no idea what it was. (Ceejay, 2006).

Retrieved from https://www.pexels.com/photo/cars-drive-driver-driving-54569/. Licensed under CC0.

Ceejay is experiencing panic disorder, a psychological disorder characterized by sudden attacks of anxiety and terror that have led to significant behavioral changes in the person’s life. Symptoms of a panic attack include shortness of breath, heart palpitations, trembling, dizziness, choking sensations, nausea, and an intense feeling of dread or impending doom. Panic attacks can often be mistaken for heart attacks or other serious physical illnesses, and they may lead the person experiencing them to go to a hospital emergency room. Panic attacks may last as little as one or as much as twenty minutes, but they often peak and subside within about ten minutes.

Sufferers are often anxious because they fear that they will have another panic attack. They focus their attention on the thoughts and images of their fears, becoming excessively sensitive to cues that signal the possibility of threat (MacLeod, Rutherford, Campbell, Ebsworthy, & Holker, 2002). They may also become unsure of the source of their arousal, misattributing it to situations that are not actually the cause. As a result, they may begin to avoid places where attacks have occurred in the past, such as a car, an elevator, or public places. Panic disorder affects about 3% of the American population in a given year.

Phobias

A phobia (from the Greek word phobos, which means “fear”) is a specific fear of a certain object, situation, or activity. The fear experience can range from a sense of unease to a full-blown panic attack. Most people learn to live with their phobias, but for others the fear can be so debilitating that they go to extremes to avoid the fearful situation. A sufferer of arachnophobia (fear of spiders), for example, may refuse to enter a room until it has been checked thoroughly for spiders, or may refuse to vacation in the countryside because spiders may be there. Phobias are characterized by their specificity and their irrationality. A person with acrophobia (a fear of height) could fearlessly sail around the world on a sailboat with no concerns yet refuse to go out onto the balcony on the fifth floor of a building. Phobias affect about 9% of American adults, and they are about twice as prevalent in women as in men (Fredrikson, Annas, Fischer, & Wik, 1996; Kessler, Meron-Ruscio, Shear, & Wittchen, 2009). In most cases, phobias first appear in childhood and adolescence and usually persist into adulthood.

A common phobia is social phobia, extreme shyness around people or discomfort in social situations. Social phobia may be specific to a certain event, such as speaking in public or using a public restroom, or it can be a more generalized anxiety toward almost all people outside of close family and friends. People with social phobia will often experience physical symptoms in public, such as sweating profusely, blushing, stuttering, nausea, and dizziness. They are convinced that everybody around them notices these symptoms as they are occurring. Women are somewhat more likely than men to suffer from social phobia.

The most incapacitating phobia is agoraphobia, defined as anxiety about being in places or situations from which escape might be difficult or embarrassing, or in which help may not be available (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Typical places that provoke the panic attacks are parking lots; crowded streets or shops; and bridges, tunnels, or expressways. People (mostly women) who suffer from agoraphobia may have great difficulty leaving their homes and interacting with other people.

- Acrophobia=Fear of heights

- Agoraphobia=Fear of situations in which escape is difficult

- Arachnophobia=Fear of spiders

- Astraphobia=Fear of thunder and lightening

- Claustrophobia=Fear of closed-in spaces

- Cynophobia=Fear of dogs

- Mysophobia=Fear of germs or dirt

- Ophidiophobia=Fear of snakes

- Pteromerhanophobia=Fear of flying

- Social phobia=Fear of social situations

- Trypanophobia=Fear of injections

- Zoophobia=Fear of small animals

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.). Washington, DC: Author.

Ceejay. (2006, September). My dance with panic [Web log post]. Panic Survivor. Retrieved from http://www.panicsurvivor.com/index.php/2007102366/Survivor-Stories/My-Dance-With-Panic.html.

Chase. (2010, February 28). Re: “anxiety?” [Online forum comment]. Mental Health Forum. Retrieved from http://www.mentalhealthforum.net/forum/showthread.php?t=9359.

Fredrikson, M., Annas, P., Fischer, H., & Wik, G. (1996). Gender and age differences in the prevalence of specific fears and phobias. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 34(1), 33–39. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(95)00048-3; Kessler, R., Meron-Ruscio, A., Shear, K., & Wittchen, H. (2009). Epidemiology of anxiety disorders. In M. Anthony, & M. Stein (Eds). Oxford handbook of anxiety and related disorders. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Kessler, R., Chiu, W., Demler, O., & Walters, E. (2005). Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 617–27; Robins, L., & Regier, D. A. (1991). Psychiatric disorders in America: The Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. New York, NY: Free Press.

MacLeod, C., Rutherford, E., Campbell, L., Ebsworthy, G., & Holker, L. (2002). Selective attention and emotional vulnerability: Assessing the causal basis of their association through the experimental manipulation of attentional bias. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 111(1), 107–123.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders

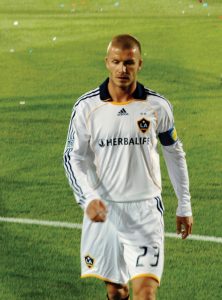

Although he is best known his perfect shots on the field, the soccer star David Beckham also suffers from Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD). As he describes it,

I have got this obsessive-compulsive disorder where I have to have everything in a straight line or everything has to be in pairs. I’ll put my Pepsi cans in the fridge and if there’s one too many then I’ll put it in another cupboard somewhere. I’ve got that problem. I’ll go into a hotel room. Before I can relax, I have to move all the leaflets and all the books and put them in a drawer. Everything has to be perfect (Dolan, 2006).

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a psychological disorder that is diagnosed when an individual continuously experiences distressing or frightening thoughts, and engages in obsessions (repetitive thoughts) or compulsions (repetitive behaviors) in an attempt to calm these thoughts. OCD is diagnosed when the obsessive thoughts are so disturbing and the compulsive behaviors are so time consuming that they cause distress and significant dysfunction in a person’s everyday life. Washing your hands once or even twice to make sure that they are clean is normal; washing them 20 times is not. Keeping your fridge neat is a good idea; spending hours a day on it is not. The sufferers know that these rituals are senseless, but they cannot bring themselves to stop them, in part because the relief that they feel after they perform them acts as a reinforcer, making the behavior more likely to occur again.

Sufferers of OCD may avoid certain places that trigger the obsessive thoughts, or use alcohol or drugs to try to calm themselves down. OCD has a low prevalence rate (about 1% of the population in a given year) in relation to other anxiety disorders, and usually develops in adolescence or early adulthood (Horwath & Weissman, 2000; Samuels & Nestadt, 1997). The course of OCD varies from person to person. Symptoms can come and go, decrease, or worsen over time.

Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Beckham_LA_Galaxy_cropped.jpg. Licensed under CC BY-2.0.

Trauma and Stressor Related Disorders

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

“If you imagine burnt pork and plastic; I can still taste it,” says Chris Duggan, on his experiences as a soldier in the Falklands War in 1982. “These helicopters were coming in and we were asked to help get the boys off . . . when they opened the doors the stench was horrendous.” When he left the army in 1986, he suffered from PTSD. “I was a bit psycho,” he says. “I was verbally aggressive, very uncooperative. I was arguing with my wife, and eventually we divorced. I decided to change the kitchen around one day, get all new stuff, so I threw everything out of the window. I was 10 stories up in a flat. I poured brandy all over the video and it melted. I flooded the bathroom.” (Gould, 2007).

People who have survived a terrible ordeal, such as combat, torture, sexual assault, imprisonment, abuse, natural disasters, or the death of someone close to them may develop posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The anxiety may begin months or even years after the event. People with PTSD experience high levels of anxiety along with re-experiencing the trauma (flashbacks), and a strong desire to avoid any reminders of the event. They may lose interest in things they used to enjoy; startle easily; have difficulty feeling affection; and may experience terror, rage, depression, or insomnia. The symptoms may be especially intense when approaching the area where the event took place or when the anniversary of that event is near.

PTSD affects about 5 million Americans, including victims of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, and Hurricane Katrina. Sixteen percent of Iraq war veterans, for example, reported experiencing symptoms of PTSD (Hoge & Castro, 2006). PTSD is a frequent outcome of childhood or adult sexual abuse, a disorder that has its own Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) diagnosis. Women are more likely to develop PTSD than men (Davidson, 2000).

Risk factors for PTSD include the degree of the trauma’s severity, the lack of family and community support, and additional life stressors (Brewin, Andrews, & Valentine, 2000). Many people with PTSD also suffer from another mental disorder, particularly depression, other anxiety disorders, and substance abuse (Brady, Back, & Coffey, 2004).

Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Damage_and_destruction_to_houses_in_Biloxi,_Mississippi_by_hurricane_Katrina_14605.jpg. Licensed under CC0 Public Domain.

Dissociative Disorders

On October 23, 2006, a man appeared on the television show Weekend Today and asked America to help him rediscover his identity. The man, who was later identified as Jeffrey Alan Ingram, had left his home in Seattle on September 9, 2006, and found himself in Denver a few days later, without being able to recall who he was or where he lived. He was reunited with family after being recognized on the show. According to a coworker of Ingram’s fiancée, even after Ingram was reunited with his fiancée, his memory did not fully return. “He said that while her face wasn’t familiar to him, her heart was familiar to him . . . He can’t remember his home, but he said their home felt like home to him.”

People who experience extreme anxiety or trauma are haunted by their memories and experiences, and although they desperately wish to get past them, they normally cannot. In some cases, however; such as with Jeffrey Ingram, people who become overwhelmed by stress experience an altered state of consciousness in which they become detached from the reality of what is happening to them. A dissociative disorder is a condition that involves disruptions or breakdowns of memory, awareness, and identity. The dissociation is used as a defense against the trauma.

Dissociative Amnesia and Fugue

Dissociative amnesia is a psychological disorder that involves extensive, but selective, memory loss, but in which there is no physiological explanation for the forgetting (van der Hart & Nijenhuis, 2009). The amnesia is normally brought on by a trauma—a situation that causes such painful anxiety that the individual “forgets” in order to escape. These kinds of trauma include disasters, accidents, physical abuse, rape, and other forms of severe stress (Cloninger & Dokucu, 2008). Although the personality of people who are experiencing dissociative amnesia remains fundamentally unchanged—and they recall how to carry out daily tasks such as reading, writing, and problem solving—they tend to forget things about their personal lives—for instance, their name, age, and occupation—and may fail to recognize family and friends (van der Hart & Nijenhuis, 2009).

Dissociative amnesia may sometimes include dissociative fugue, in which an individual loses complete memory of his or her identity and may even assume a new one, often far from home. The individual with dissociative fugue experiences all the symptoms of dissociative amnesia but also leaves the situation entirely. The fugue state may last for just a matter of hours or may continue for months, as it did with Jeffrey Ingram. Recovery from the fugue state tends to be rapid, but when people recover, they commonly have no memory of the stressful event that triggered the fugue or of events that occurred during their fugue state (Cardeña & Gleaves, 2007).

Dissociative Identity Disorder

You may remember the story of Sybil (a pseudonym for Shirley Ardell Mason, who was born in 1923), a person who, over a period of 40 years, claimed to possess 16 distinct personalities. Mason was in therapy for many years trying to integrate these personalities into one complete self. A TV movie about Mason’s life, starring Sally Field as Sybil, appeared in 1976.

Sybil suffered from the most severe of the dissociative disorders, dissociative identity disorder. Dissociative identity disorder is a psychological disorder in which two or more distinct and individual personalities exist in the same person, and there is an extreme memory disruption regarding personal information about the other personalities (van der Hart & Nijenhuis, 2009). Dissociative identity disorder was once known as “multiple personality disorder,” and this label is still sometimes used. This disorder is sometimes mistakenly referred to as schizophrenia.

In some cases of dissociative identity disorder, there can be more than 10 different personalities in one individual. Switches from one personality to another tend to occur suddenly, often triggered by a stressful situation (Gillig, 2009). The host personality is the personality in control of the body most of the time, and the alter personalities tend to differ from each other in terms of age, race, gender, language, manners, and even sexual orientation (Kluft, 1996). A shy, introverted individual may develop a boisterous, extroverted alter personality. Each personality has unique memories and social relationships (Dawson, 1990). Women are more frequently diagnosed with dissociative identity disorder than are men, and when they are diagnosed also tend to have more “personalities” (American Psychiatric Association, 2000).

The dissociative disorders are relatively rare conditions and are most frequently observed in adolescents and young adults. In part because they are so unusual and difficult to diagnose, clinicians and researchers disagree about the legitimacy of the disorders, and particularly, about dissociative identity disorder. Some clinicians argue that the descriptions in the DSM accurately reflect the symptoms of these patients, whereas others believe that patients are faking, role-playing, or using the disorder as a way to justify behavior (Barry-Walsh, 2005; Kihlstrom, 2004; Lilienfeld & Lynn, 2003; Lipsanen et al., 2004). Even the diagnosis of Shirley Ardell Mason (Sybil) is disputed. Some experts claim that Mason was highly hypnotizable and that her therapist unintentionally “suggested” the existence of her multiple personalities (Miller & Kantrowitz, 1999).

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.). Washington, DC: Author.

Barry-Walsh, J. (2005). Dissociative identity disorder. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 39, 109–110; Kihlstrom, J. F. (2004). An unbalanced balancing act: Blocked, recovered, and false memories in the laboratory and clinic. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11(1), 34–41; Lilienfeld, S. O., & Lynn, S. J. (2003). Dissociative identity disorder: Multiple personalities, multiple controversies. In S. O. Lilienfeld, S. J. Lynn, & J. M. Lohr (Eds.), Science and pseudoscience in clinical psychology (pp. 109–142). New York, NY: Guilford Press; Lipsanen, T., Korkeila, J., Peltola, P., Jarvinen, J., Langen, K., & Lauerma, H. (2004). Dissociative disorders among psychiatric patients: Comparison with a nonclinical sample. European Psychiatry, 19(1), 53–55.

Brady, K. T., Back, S. E., & Coffey, S. F. (2004). Substance abuse and posttraumatic stress disorder. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13(5), 206–209.

Brewin, C., Andrews, B., & Valentine, J. (2000). Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(5), 748–766. doi:10.1037//0022-006X.68.5.748.

Cardeña, E., & Gleaves, D. (2007). Dissociative disorders. In M. M. Hersen, S. M. Turner, & D. C. Beidel (Eds.), Adult psychological disorder and diagnosis (5th ed., pp. 473–503). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Cloninger, C., & Dokucu, M. (2008). Somatoform and dissociative disorders. In S. H. Fatemi & P. J. Clayton (Eds.), The medical basis of psychiatry (3rd ed., pp. 181–194). Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. doi:10.1007/978-1-59745-252-6_11.

Davidson, J. (2000). Trauma: The impact of post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 14(2 Suppl 1), S5–S12.

Dawson, P. L. (1990). Understanding and cooperation among alter and host personalities. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 44(11), 994–997.

Dolan, A. (2006, April 3). The obsessive disorder that haunts my life. Daily Mail. Retrieved from http://www.dailymail.co.uk/tvshowbiz/article-381802/The-obsessive-disorder-haunts-life.html.

Gillig, P. M. (2009). Dissociative identity disorder: A controversial diagnosis. Psychiatry, 6(3), 24–29.

Gould, M. (2007, October 10). You can teach a man to kill but not to see dying. The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/2007/oct/10/guardiansocietysupplement.socialcare2.

Hoge, C., & Castro, C. (2006). Post-traumatic stress disorder in UK and U.S. forces deployed to Iraq. Lancet, 368, 867.

Horwath, E., & Weissman, M. (2000). The epidemiology and cross-national presentation of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 23(3), 493–507. doi:10.1016/S0193-953X(05)70176-3; Samuels, J., & Nestadt, G. (1997). Epidemiology and genetics of obsessive-compulsive disorder. International Review of Psychiatry, 9, 61–71.

Kluft, R. P. (1996). The diagnosis and treatment of dissociative identity disorder. In The Hatherleigh guide to psychiatric disorders (1st ed., Vol. 1, pp. 49–96). New York, NY: Hatherleigh Press.

Miller, M., & Kantrowitz, B. (1999, January 25). Unmasking Sybil: A reexamination of the most famous psychiatric patient in history. Newsweek, pp. 11–16.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

van der Hart, O., & Nijenhuis, E. R. S. (2009). Dissociative disorders. In P. H. Blaney & T. M. Millon (Eds.), Oxford textbook of psychological disorder (2nd ed., pp. 452–481). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Anxiety, Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, Trauma and Dissociative Identity Disorders

Melissa Schaeer (2014, Nov. 24). Anxiety, Obsessive Compulsive, and Trauma related disorders [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YdPH2wIyurY. Standard YouTube license.

Osmosis. (2017, November 20). Dissociative disorders-Causes, symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, pathology. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XF2zeOdE5GY&t=6s. Standard YouTube License.

Summary

In this section we explored the impact of anxiety disorders and phobias. Anxiety disorders are psychological disturbances marked by irrational fears, often of everyday objects and situations. They include generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder, and phobias. Anxiety is a natural part of life, but too much anxiety can be debilitating. Anxiety disorders affect about 57 million Americans every year.

In this section we also reviewed obsessive-compulsive disorders, trauma, and dissociative disorders. As you’ve learned, the disorders explored in this section were once categorized as anxiety disorders, but are no longer regarded as such in the DSM-5. Obsessive-compulsive disorder is characterized by repetitive thoughts and compulsive behaviors that cause distress and significant disruption to a person’s everyday life.

People who have survived a terrible ordeal, such as combat, torture, rape, imprisonment, abuse, natural disasters, or the death of someone close to them, may develop PTSD. People with PTSD experience high levels of anxiety along with re-experiencing the trauma (flashbacks), and a strong desire to avoid any reminders of the event. PTSD affects approximately 5 million people.

Dissociative disorders are conditions that involve disruptions or breakdowns of memory, awareness, and identity. They include dissociative amnesia, dissociative fugue, and dissociative identity disorder.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.