Conformity, Compliance, and Obedience

Introduction

In this section we will explore conformity, compliance, and obedience and its impact on society and behavior. As you have learned in previous sections, people have developed a variety of social skills that enhance our ability to successfully interact with others. While we are independent thinkers influenced by both nature and nurture, we also have a tendency to conform to our friends and family at times. Think about a time when you sought out advice and followed it, even if that was not what you really wanted to do. For instance, when we decide on what courses to enroll in by asking for advice from our friends, change our beliefs or behaviors as a result of the ideas that we hear from others, or binge drink because our friends are doing it, we are engaging in conformity, a change in beliefs or behavior that occurs as the result of the presence of the other people around us. We conform not only because we believe that other people have accurate information and we want to have knowledge (informational conformity) but also because we want to be liked by others (normative conformity). The typical outcome of conformity is that our beliefs and behaviors become more similar to those of others around us.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Conformity, Compliance and Obedience

Social Norms

At times, conformity occurs in a relatively spontaneous and unconscious way, without any obvious intent of one person to change the other, or an awareness that the conformity is occurring. Robert Cialdini and his colleagues (Cialdini, Reno, & Kallgren, 1990) found that college students were more likely to throw litter on the ground themselves when they had just seen another person throw some paper on the ground, and Cheng and Chartrand (2003) found that people unconsciously mimicked the behaviors of others, such as by rubbing their face or shaking their foot, and that that mimicry was greater when the other person was of high versus low social status.

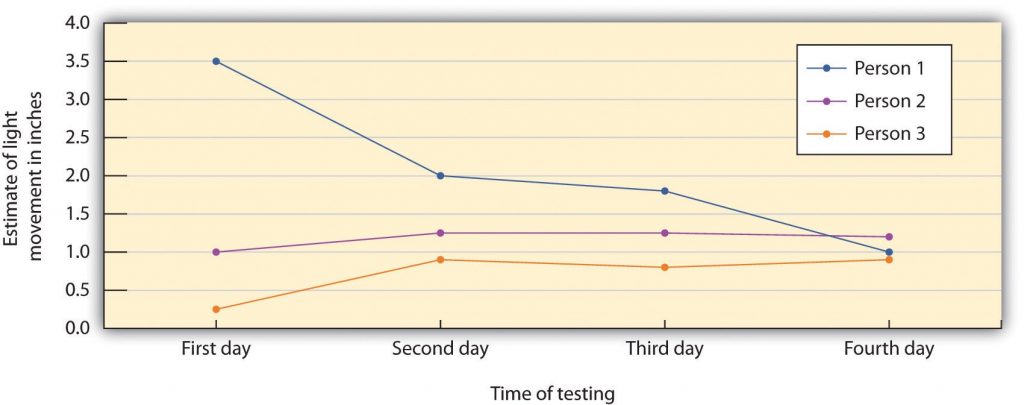

Muzafer Sherif (1936) studied how norms develop in ambiguous situations. In his studies, college students were placed in a dark room with a single point of light and were asked to indicate, each time the light was turned on, how much it appeared to move. (The movement, which is not actually real, occurs because of the saccadic movement of the eyes.) Each group member gave his or her response on each trial aloud and each time in a different random order. Sherif found a conformity effect: Over time, the responses of the group members became more and more similar to each other such that after 4 days they converged on a common norm. When the participants were interviewed after the study, they indicated that they had not realized that they were conforming. (Stangor, 2017)

Source: Adapted from Sherif, M. (1936). The psychology of social norms. New York, NY: Harper and Row.Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Not all conformity is passive. What factors make a person more likely to yield to group pressure? Research shows that the size of the majority, the presence of another dissenter, and the public or relatively private nature of responses are key influences on conformity.

- The size of the majority: The greater the number of people in the majority, the more likely an individual will conform. There is, however, an upper limit: a point where adding more members does not increase conformity.

- The presence of another dissenter: If there is at least one dissenter, conformity rates drop to near zero (Asch, 1955).

- The public or private nature of the responses: When responses are made publicly (in front of others), conformity is more likely; however, when responses are made privately (e.g., writing down the response), conformity is less likely (Deutsch & Gerard, 1955).

The Asch effect is the influence of the group majority on an individual’s judgment. The finding that conformity is more likely to occur when responses are public than when they are private is the reason government elections require voting in secret, so we are not coerced by others. The Asch effect can be easily seen in children when they have to publicly vote for something. For example, if the teacher asks whether the children would rather have extra recess, no homework, or candy, once a few children vote, the rest will comply and go with the majority. In a different classroom, the majority might vote differently, and most of the children would comply with that majority. When someone’s vote changes if it is made in public versus private, this is known as compliance. Compliance can be a form of conformity. Compliance is going along with a request or demand, even if you do not agree with the request. (OpenStax, 2014)

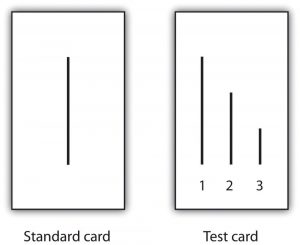

In the research of Solomon Asch (1955), the judgments that group members were asked to make were entirely unambiguous, and the influence of the other people on judgments was apparent. The research participants were male college students who were told that they were to be participating in a test of visual abilities. The men were seated in front of a board that displayed the visual stimuli that they were going to judge. The men were told that there would be 18 trials during the experiment, and on each trial they would see two cards. The standard card had a single line that was to be judged, and the test card had three lines that varied in length between about 2 and 10 inches.

On each trial, each person in the group answered out loud, beginning with one end of the group and moving toward the other end. Although the real research participant did not know it, the other group members were actually not participants but experimental confederates who gave predetermined answers on each trial. Because the real participant was seated next to the last in the row, he always made his judgment following most of the other group members. Although on the first two trials the confederates each gave the correct answer, on the third trial, and on 11 of the subsequent trials, they all had been instructed to give the same wrong choice. For instance, even though the correct answer was Line 1, they would all say it was Line 2. Thus when it became the participant’s turn to answer, he could either give the clearly correct answer or conform to the incorrect responses of the confederates.

Remarkably, in this study about 76% of the 123 men who were tested gave at least one incorrect response when it was their turn, and 37% of the responses, overall, were conforming. This is indeed evidence for the power of conformity because the participants were making clearly incorrect responses in public. However, conformity was not absolute; in addition to the 24% of the men who never conformed, only 5% of the men conformed on all 12 of the critical trials. (Stangor, 2017)

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Asch, S. (1955). Opinions and social pressure. Scientific American, 11, 32.

Cheng, C. M., & Chartrand, T. L. (2003). Self-monitoring without awareness: Using mimicry as a nonconscious affiliation strategy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(6), 1170–1179.

Cialdini, R. B., Reno, R. R., & Kallgren, C. A. (1990). A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 1015–1026.

OpenStax, Conformity, Compliance, and Obedience. OpenStax CNX. Dec 22, 2014 http://cnx.org/contents/f80efb42-fea3-4b06-94cf-a8bdd8f37f20@6. Retrieved from https://cnx.org/contents/Sr8Ev5Og@5.52:-A77Qv6j@6/Conformity-Compliance-and-Obed. Licensed under CC BY-4.0.

Sherif, M. (1936). The psychology of social norms. New York, NY: Harper and Row.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Obedience

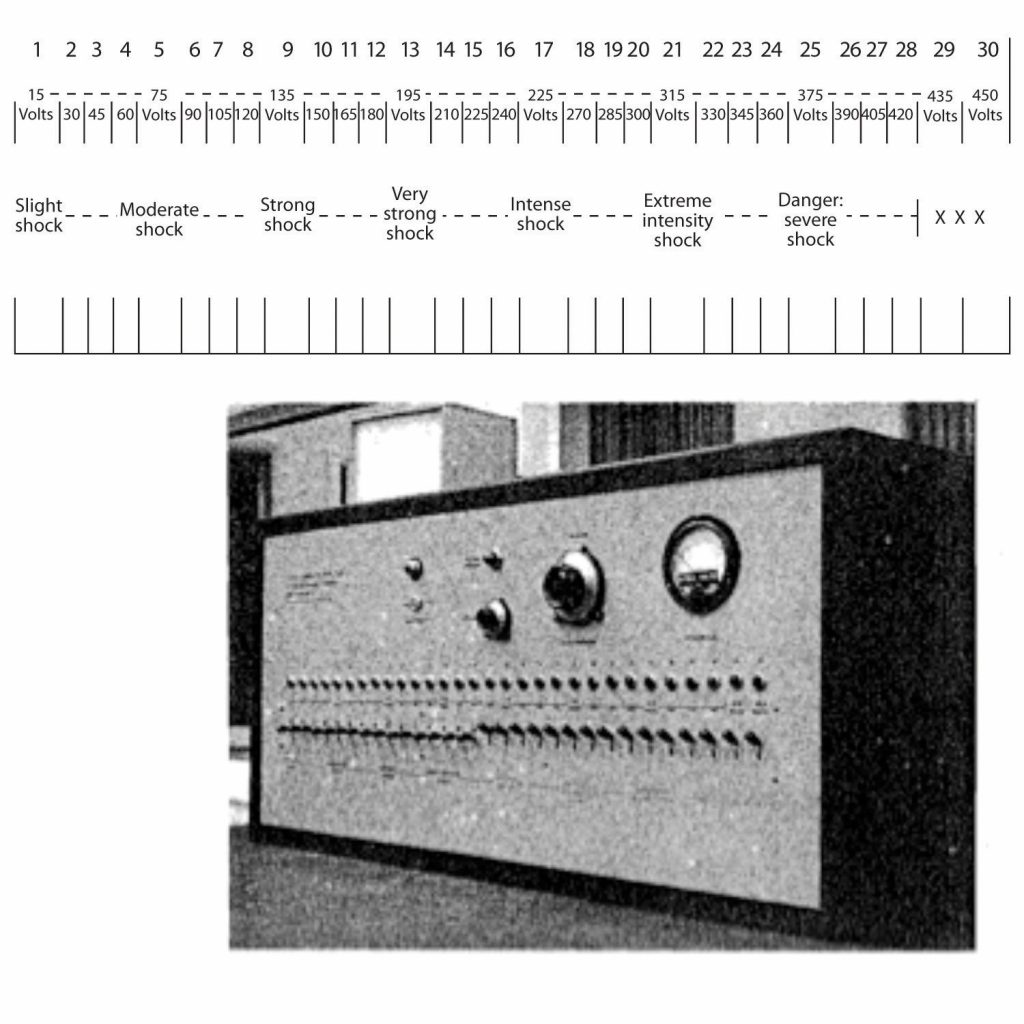

The tendency to conform to those in authority, known as obedience, was demonstrated in a remarkable set of studies performed by Stanley Milgram (1974). Milgram designed a study in which he could observe the extent to which a person who presented himself as an authority would be able to produce obedience, even to the extent of leading people to cause harm to others. Like many other researchers who were interested in conformity, Milgram’s interest stemmed in part from his desire to understand how the presence of a powerful social situation—in this case the directives of Adolph Hitler, the German dictator who ordered the killing of millions of Jews and other “undesirable” people during World War II—could produce obedience.

Milgram used newspaper ads to recruit men (and in one study, women) from a wide variety of backgrounds to participate in his research. When the research participant arrived at the lab, he or she was introduced to a man who appeared to be another research participant but who actually was a confederate working with the experimenter as part of the experimental team. The experimenter explained that the goal of the research was to study the effects of punishment on learning. After the participant and the confederate both consented to be in the study, the researcher explained that one of them would be the teacher, and the other the learner. They were each given a slip of paper and asked to open it and indicate what it said. In fact both papers read “teacher,” which allowed the confederate to pretend that he had been assigned to be the learner and thus to assure that the actual participant was always the teacher.

While the research participant (now the teacher) looked on, the learner was taken into the adjoining shock room and strapped to an electrode that was to deliver the punishment. The experimenter explained that the teacher’s job would be to sit in the control room and read a list of word pairs to the learner. After the teacher read the list once, it would be the learner’s job to remember which words went together. For instance, if the word pair was “blue sofa,” the teacher would say the word “blue” on the testing trials, and the learner would have to indicate which of four possible words (“house,” “sofa,” “cat,” or “carpet”) was the correct answer by pressing one of four buttons in front of him.

After the experimenter gave the “teacher” a mild shock to demonstrate that the shocks really were painful, the experiment began. The research participant first read the list of words to the learner and then began testing him on his learning. The shock apparatus was in front of the teacher, and the learner was not visible in the shock room. The experimenter sat behind the teacher and explained to him that each time the learner made a mistake he was to press one of the shock switches to administer the shock. Moreover, the switch that was to be pressed increased by one level with each mistake, so that each mistake required a stronger shock.

Source: Adapted from Milgram, S. (1974). Obedience to authority: An experimental view. New York, NY: Harper and Row.Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Once the learner (who was, of course, actually the experimental confederate) was alone in the shock room, he unstrapped himself from the shock machine and brought out a tape recorder that he used to play a prerecorded series of responses that the teacher could hear through the wall of the room.

The teacher heard the learner say “ugh!” after the first few shocks. After the next few mistakes, when the shock level reached 150 V, the learner was heard to exclaim, “Let me out of here. I have heart trouble!” As the shock reached about 270 V, the protests of the learner became more vehement, and after 300 V the learner proclaimed that he was not going to answer any more questions. From 330 V and up, the learner was silent. At this point the experimenter responded to participants’ questions, if any, with a scripted response indicating that they should continue reading the questions and applying increasing shock when the learner did not respond.

The results of Milgram’s research were themselves quite shocking. Although all the participants gave the initial mild levels of shock, responses varied after that. Some refused to continue after about 150 V, despite the insistence of the experimenter to continue to increase the shock level. Still others, however; continued to present the questions and to administer the shocks, under the pressure of the experimenter, who demanded that they continue. In the end, 65% of the participants continued giving the shock to the learner all the way up to the 450 V maximum, even though that shock was marked as “danger: severe shock” and no response had been heard from the participant for several trials. In other words, well over half of the men who participated had, as far as they knew, shocked another person to death, all as part of a supposed experiment on learning.

In case you are thinking that such high levels of obedience would not be observed in today’s modern culture, there is fact evidence that they would. Milgram’s findings were almost exactly replicated, using men and women from a wide variety of ethnic groups, in a study conducted this decade at Santa Clara University (Burger, 2009). In this replication of the Milgram experiment, 67% of the men and 73% of the women agreed to administer increasingly painful electric shocks when an authority figure ordered them to. The participants in this study were not, however; allowed to go beyond the 150 V shock switch.

Although it might be tempting to conclude that Burger’s and Milgram’s experiments demonstrate that people are innately bad creatures who are ready to shock others to death, this is not in fact the case. Rather it is the social situation, and not the people themselves, that is responsible for the behavior. When Milgram created variations on his original procedure, he found that changes in the situation dramatically influenced the amount of conformity. Conformity was significantly reduced when people were allowed to choose their own shock level rather than being ordered to use the level required by the experimenter, when the experimenter communicated by phone rather than from within the experimental room, and when other research participants refused to give the shock. These findings are consistent with a basic principle of social psychology: The situation in which people find themselves has a major influence on their behavior.

Burger, J. M. (2009). Replicating Milgram: Would people still obey today? American Psychologist, 64(1), 1–11

Milgram, S. (1974). Obedience to authority: An experimental view. New York, NY: Harper and Row.

Do We Always Conform?

The research that we have discussed to this point suggests that most people conform to the opinions and desires of others. But it is not always the case that we blindly conform — some people, in some situations, react to conformity pressure in ways that prevent them from being overly influenced by social pressure (Swann & Jetten, 2017). For one, there are individual differences in conformity. People with lower self-esteem are more likely to conform than are those with higher self-esteem, and people who are dependent on and who have a strong need for approval from others are also more conforming (Bornstein, 1993). People who highly identify with or who have a high degree of commitment to a group are also more likely to conform to group norms than those who care less about the group (Jetten, Spears, & Manstead, 1997). Despite these individual differences among people in terms of their tendency to conform, however; research has generally found that the impact of individual difference variables on conformity is smaller than the influence of situational variables, such as the number and unanimity of the majority.

We have seen that conformity usually occurs such that the opinions and behaviors of individuals become more similar to the opinions and behaviors of the majority of the people in the group. However, and although it is much more unusual, there are cases in which a smaller number of individuals is able to influence the opinions or behaviors of the larger group—a phenomenon known as minority influence. Minorities who are consistent and confident in their opinions may in some cases be able to be persuasive (Moscovici, Mugny, & Van Avermaet, 1985).

Persuasion that comes from minorities has another, and potentially even more important, effect on the opinions of majority group members: It can lead majorities to engage in fuller, as well as more divergent, innovative, and creative thinking about the topics being discussed (Martin, Hewstone, Martin, & Gardikiotis, 2008). Nemeth and Kwan (1987) found that participants working together in groups solved problems more creatively when only one person gave a different and unusual response than the other members did (minority influence) in comparison to when three people gave the same unusual response.

It is a good thing that minorities can be influential; otherwise, the world would be pretty boring indeed. When we look back on history, we find that it is the unusual, divergent, innovative minority groups or individuals, who—although frequently ridiculed at the time for their unusual ideas—end up being respected for producing positive changes.

Another case where conformity does not occur is when people feel that their freedom is being threatened by influence attempts, yet they also have the ability to resist that persuasion. In these cases they may develop a strong emotional reaction that leads people to resist pressures to conform known as psychological reactance (Miron & Brehm, 2006). Reactance is aroused when our ability to choose which behaviors to engage in is eliminated or threatened with elimination. The outcome of the experience of reactance is that people may not conform at all, in fact moving their opinions or behaviors away from the desires of the influencer.

Consider an experiment conducted by Pennebaker and Sanders (1976), who attempted to get people to stop writing graffiti on the walls of campus restrooms. In the first group of restrooms they put a sign that read “Do not write on these walls under any circumstances!” whereas in the second group they placed a sign that simply said “Please don’t write on these walls.” Two weeks later, the researchers returned to the restrooms to see if the signs had made a difference. They found that there was significantly less graffiti in the second group of restrooms than in the first one. It seems as if people who were given strong pressures to not engage in the behavior were more likely to react against those directives than were people who were given a weaker message.

Reactance represents a desire to restore freedom that is being threatened. A child who feels that his or her parents are forcing him to eat his asparagus may react quite vehemently with a strong refusal to touch the plate. And an adult who feels that she is being pressured by a car salesman might feel the same way and leave the showroom entirely, resulting in the opposite of the salesman’s intended outcome.

Bornstein, R. F. (1993). The dependent personality. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Jetten, J., Spears, R., & Manstead, A. S. R. (1997). Strength of identification and intergroup differentiation: The influence of group norms. European Journal of Social Psychology, 27(5), 603–609.

Pennebaker, J. W., & Sanders, D. Y. (1976). American graffiti: Effects of authority and reactance arousal. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 2(3), 264–267.

Miron, A. M., & Brehm, J. W. (2006). Reaktanz theorie—40 Jahre sparer. Zeitschrift fur Sozialpsychologie, 37(1), 9–18.

Martin, R., Hewstone, M., Martin, P. Y., & Gardikiotis, A. (2008). Persuasion from majority and minority groups. In W. D. Crano & R. Prislin (Eds.), Attitudes and attitude change (pp. 361–384). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Moscovici, S., Mugny, G., & Van Avermaet, E. (1985). Perspectives on minority influence. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Nemeth, C., & Kwan, J. L. (1987). Minority influence, divergent thinking and the detection of correct solutions. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 17, 788–799.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Swann, W. B., & Jetten, J. (2017). Restoring Agency to the Human Actor. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(3), 382–399. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691616679464.

Conformity, Compliance, and Obedience-Video

Khanacademymedicine. (2015, April 3). Conformity and obedience [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Loy1zLkbuF0. Standard YouTube license.

CrashCourse. (2014, November 11). Social influence: Crash course psychology #38. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UGxGDdQnC1Y. Standard YouTube License.

Summary

In this section we explored conformity, compliance, and obedience. The situation is the most powerful determinant of conformity, but individual difference may also matter. The important influence of the social situation on conformity was demonstrated in the research by Sherif, Asch, Milgram, and others.

The tendency to conform to those in authority, known as obedience, was demonstrated in a remarkable set of studies performed by Stanley Milgram (1974). Milgram designed a study in which he could observe the extent to which a person who presented himself as an authority figure would be able to produce obedience, even to the extent of leading people to cause harm to others.

Minority influence can change attitudes and change how majorities process information. We conform not only because we believe that other people have accurate information and we want to have knowledge (informational conformity) but also because we want to be liked by others (normative conformity). The typical outcome of conformity is that our beliefs and behaviors become more similar to those of others around us. Although majorities are most persuasive, numerical minorities that are consistent and confident in their opinions may in some cases be able to be persuasive.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.