Infant and Early Childhood Development

Introduction

The first year and a half to two years of life are ones of dramatic growth and change. A newborn, with a keen sense of hearing but very poor vision, is transformed into a walking, talking toddler within a relatively short period of time. Caregivers are also transformed from someone who manages feeding and sleep schedules to a constantly moving guide and safety inspector for a mobile, energetic child. Early childhood is also referred to as the preschool years consisting of the years which follow toddlerhood and precede formal schooling. As a three to five-year-old, the child is busy learning language, is gaining a sense of self and greater independence, and is beginning to learn the workings of the physical world. This knowledge does not come quickly, however; and pre-schoolers may have initially interesting conceptions of size, time, space and distance such as fearing that they may go down the drain if they sit at the front of the bathtub or by demonstrating how long something will take by holding out their two index fingers several inches apart. A toddler’s fierce determination to do something may give way to a four-year-old’s sense of guilt for doing something that brings the disapproval of others. The ages of six through eleven comprise middle childhood and much of what children experience at this age is connected to their involvement in the early grades of school. Now the world becomes one of learning and testing new academic skills and by assessing one’s abilities and accomplishments by making comparisons between self and others. Schools compare students and make these comparisons public through team sports, test scores, and other forms of recognition. Growth rates slow down and children are able to refine their motor skills at this point in life. Children begin to learn about social relationships beyond the family through interaction with friends and fellow students.

Psyc 200 Lifespan Psychology. Authored by Laura Overstreet. Located at http://opencourselibrary.org/econ-201/. Licensed under CC BY-4.0. Retrieved from https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-lifespandevelopment2/chapter/periods-of-development/.

Infancy and Childhood Development

Physical Development during Infancy and Childhood

On average, a baby is born sometime around the 38th week of pregnancy. The fetus is responsible, at least in part, for its own birth due to chemicals that are released by the developing fetal brain. These chemicals trigger the muscles in the mother’s uterus to start the rhythmic contractions of childbirth. The contractions are initially spaced at about 15-minute intervals but come more rapidly with time as labor progresses. When the contractions reach an interval of 2 to 3 minutes, the mother is requested to assist in the labor and help push the baby out. Newborns are already prepared to face the new world they are about to experience. Babies are equipped with a variety of reflexes, each providing an ability that will help them survive their first few months of life as they continue to learn new routines to help them survive in and manipulate their environments.

In addition to reflexes, newborns have preferences—they like sweet tasting foods at first, while becoming more open to salty items by 4 months of age (Beauchamp, Cowart, Menellia, & Marsh, 1994; Blass & Smith, 1992). Newborns also prefer the smell of their mothers. An infant at only 6 days old is significantly more likely to turn toward its own mother’s breast pad than to the breast pad of another baby’s mother (Porter, Makin, Davis, & Christensen, 1992), and a newborn also shows a preference for the face of its own mother (Bushnell, Sai, & Mullin, 1989).

Although infants are born ready to engage in some activities, their development continues over time. The child’s knowledge and abilities increase as it babbles, talks, crawls, tastes, grasps, plays, and interacts with the objects in the environment (Gibson, Rosenzweig, & Porter, 1988; Gibson & Pick, 2000; Smith & Thelen, 2003). Parents may help in this process by providing a variety of activities and experiences for the child. Research has found that animals raised in environments with more novel objects and that engage in a variety of stimulating activities have more brain synapses and larger cerebral cortexes, and they perform better on a variety of learning tasks compared with animals raised in more impoverished environments (Juraska, Henderson, & Müller, 1984). Parallels have been drawn in regards to children who have opportunities to play, explore, and interact with their environments (Soska, Adolph, & Johnson, 2010).

| Name | Stimulus | Response | Significance |

| Rooting Reflex | The baby’s cheek is stroked. | The baby turns its head toward the stroking, opens its mouth, and tries to suck. | Ensures the infant’s feeding will be a reflexive habit. |

| Blink Reflex | A light is flashed in the baby’s eyes. | The baby closes both eyes. | Protects eyes from strong and potentially dangerous stimuli. |

| Withdrawal Reflex | A soft pinprick is applied to the sole of the baby’s foot. | The baby reflexes the leg. | Keeps the exploring infant away from painful stimuli. |

| Tonic Neck Reflex | The baby is laid down on its back. | The baby turns its head to one side and extends the arm on the same side. | Helps develop hand-eye coordination. |

| Grasp Reflex | An object is pressed into the palm of the baby. | The baby grasps the object pressed and can even hold its own weight for a brief period. | Helps in exploratory learning. |

| Moro Reflex | Loud noises or a sudden drop in height while holding the baby. | The baby extends the arms and legs and quickly brings them in as if trying to grasp for something. | Protects from falling; could have assisted infants in holding onto their mothers during rough traveling. |

| Stepping Reflex | The baby is suspended with bare feet just above a surface and is moved forward. | Baby makes stepping motions as if trying to walk. | Helps encourage motor development. |

During infancy and childhood, growth does not occur at a steady rate (Carel, Lahlou, Roger, & Chaussain, 2004). Growth slows between 4 and 6 years old: During this time children gain 5–7 pounds and grow about 2–3 inches per year. Once girls reach 8–9 years old, their growth rate outpaces that of boys due to a pubertal growth spurt. This growth spurt continues until around 12 years old, coinciding with the start of the menstrual cycle. By 10 years old, the average girl weighs 88 pounds, and the average boy weighs 85 pounds.

We are born with all of the brain cells that we will ever have—about 100–200 billion neurons (nerve cells) whose function is to store and transmit information (Huttenlocher & Dabholkar, 1997). However, the nervous system continues to grow and develop. Each neural pathway forms thousands of new connections during infancy and toddlerhood. This period of rapid neural growth is called blooming. Neural pathways continue to develop through puberty. The blooming period of neural growth is then followed by a period of pruning, where neural connections are reduced. It is thought that pruning causes the brain to function more efficiently, allowing for mastery of more complex skills (Hutchinson, 2011). Blooming occurs during the first few years of life, and pruning continues through childhood and into adolescence in various areas of the brain.

The size of our brains increases rapidly. For example, the brain of a 2-year-old is 55% of its adult size, and by 6 years old the brain is about 90% of its adult size (Tanner, 1978). During early childhood (ages 3–6), the frontal lobes grow rapidly, which are associated with planning, reasoning, memory, and impulse control. Therefore, by the time children reach school age, they are developmentally capable of controlling their attention and behavior. Through the elementary school years, the frontal, temporal, occipital, and parietal lobes all grow in size. The brain growth spurts experienced in childhood tend to follow Piaget’s sequence of cognitive development, so that significant changes in neural functioning account for cognitive advances (Kolb & Whishaw, 2009; Overman, Bachevalier, Turner, & Peuster, 1992).

Motor development occurs in an orderly sequence as infants move from reflexive reactions (e.g., sucking and rooting) to more advanced motor functioning. For instance, babies first learn to hold their heads up, then to sit with assistance, and then to sit unassisted, followed later by crawling and then walking.

Motor skills refer to our ability to move our bodies and manipulate objects. Fine motor skills focus on the muscles in our fingers, toes, and eyes, and enable coordination of small actions (e.g., grasping a toy, writing with a pencil, and using a spoon). Gross motor skills focus on large muscle groups that control our arms and legs and involve larger movements (e.g., balancing, running, and jumping).

As motor skills develop, there are certain developmental milestones that young children should achieve. For each milestone there is an average age, as well as a range of ages in which the milestone should be reached. An example of a developmental milestone is sitting. On average, most babies sit alone at 7 months old. Sitting involves both coordination and muscle strength, and 90% of babies achieve this milestone between 5 and 9 months old. In another example, babies on average are able to hold up their head at 6 weeks old, and 90% of babies achieve this between 3 weeks and 4 months old. If a baby is not holding up his head by 4 months old, he is showing a delay. If the child is displaying delays on several milestones, that is reason for concern, and the parent or caregiver should discuss this with the child’s pediatrician. Some developmental delays can be identified and addressed through early intervention. (OpenStax, 2016)

Beauchamp, D. K., Cowart, B. J., Menellia, J. A., & Marsh, R. R. (1994). Infant salt taste: Developmental, methodological, and contextual factors. Developmental Psychology, 27, 353–365; Blass, E. M., & Smith, B. A. (1992). Differential effects of sucrose, fructose, glucose, and lactose on crying in 1- to 3-day-old human infants: Qualitative and quantitative considerations. Developmental Psychology, 28, 804–810.

Bushnell, I. W. R., Sai, F., & Mullin, J. T. (1989). Neonatal recognition of the mother’s face. British Journal of developmental psychology, 7, 3–15.

Gibson, E. J., Rosenzweig, M. R., & Porter, L. W. (1988). Exploratory behavior in the development of perceiving, acting, and the acquiring of knowledge. In Annual review of psychology (Vol. 39, pp. 1–41). Palo Alto, CA: Annual Reviews; Gibson, E. J., & Pick, A. D. (2000). An ecological approach to perceptual learning and development. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; Smith, L. B., & Thelen, E. (2003). Development as a dynamic system. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 7(8), 343–348.

Juraska, J. M., Henderson, C., & Müller, J. (1984). Differential rearing experience, gender, and radial maze performance. Developmental Psychobiology, 17(3), 209–215.

OpenStax. (2016, October 31). Psychology. OpenStax Psychology. Retrieved from https://cnx.org/contents/Sr8Ev5Og@5.52:b7opmCF3@6/Stages-of-Development#Figure_09_02_Stages. Licensed under CC BY-4.0.

Porter, R. H., Makin, J. W., Davis, L. B., & Christensen, K. M. (1992). Breast-fed infants respond to olfactory cues from their own mother and unfamiliar lactating females. Infant Behavior & Development, 15(1), 85–93.

Soska, K. C., Adolph, K. E., & Johnson, S. P. (2010). Systems in development: Motor skill acquisition facilitates three-dimensional object completion. Developmental Psychology, 46(1), 129–138.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Cognitive Development during Infancy and Childhood

Childhood is a time in which changes occur quickly. The child is growing physically, and cognitive abilities are also developing. During this time the child learns to actively manipulate and control the environment, and is first exposed to the requirements of society, particularly the need to control the bladder and bowels. According to Erik Erikson, the challenges that the child must attain in childhood relate to the development of initiative, competence, and independence. Children need to learn to explore the world, to become self-reliant, and to make their own way in the environment.

Retrieved from https://www.flickr.com/photos/mirjoran/455878802. Licensed under CC BY-2.0.

These skills do not come overnight. Neurological changes during childhood provide children with the ability to do certain things are certain ages, and yet make it impossible for them to do other things. This fact was made apparent through the groundbreaking work of the Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget. During the 1920s, Piaget was administering intelligence tests to children in an attempt to determine the kinds of logical thinking that children were capable of. In the process of testing the children, Piaget became intrigued, not so much by the answers that the children got right, but more by the answers they got wrong. Piaget believed that the incorrect answers that the children gave were not mere shots in the dark but rather represented specific ways of thinking unique to the children’s developmental stage. Just as almost all babies learn to roll over before they learn to sit up by themselves, and learn to crawl before they learn to walk, Piaget believed that children gain their cognitive ability in a developmental order. These insights—that children at different ages think in fundamentally different ways—led to Piaget’s stage model of cognitive development. Piaget argued that children do not just passively learn but also actively try to make sense of their worlds. He argued that, as they learn and mature, children develop schemas—patterns of knowledge in long-term memory—that help them remember, organize, and respond to information. Furthermore, Piaget thought that when children experience new things, they attempt to reconcile the new knowledge with existing schemas. Piaget believed that the children use two distinct methods in doing so, methods that he called assimilation and accommodation.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

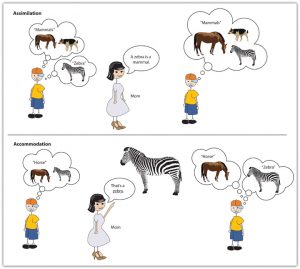

When children employ assimilation, they use already developed schemas to understand new information. If children have learned a schema for horses, then they may call the striped animal they see at the zoo a horse rather than a zebra. In this case, children fit the existing schema to the new information and label the new information with the existing knowledge. Accommodation, on the other hand, involves learning new information, and thus changing the schema. When a mother says, “No, honey, that’s a zebra, not a horse,” the child may adapt the schema to fit the new stimulus, learning that there are different types of four-legged animals, only one of which is a horse.

Piaget’s Theory on Cognitive Development

Piaget’s most important contribution to understanding cognitive development, and the fundamental aspect of his theory, was the idea that development occurs in unique and distinct stages, with each stage occurring at a specific time, in a sequential manner, and in a way that allows the child to think about the world using new capacities.

| Stage | Approximate Age Range | Characteristics | Stage Attainments |

| Sensorimotor | Birth to about 2 years | The child experiences the world through the fundamental senses of seeing, hearing, touching, and tasting. | Object permanence |

| Preoperational | 2 to 7 years | Children acquire the ability to internally represent the world through language and mental imagery. They also start to see the world from other people’s perspectives. | Theory of mind; rapid increase in language ability |

| Concrete operational | 7 to 11 years | Children become able to think logically. They can increasingly perform operations on objects that are only imagined. | Conservation |

| Formal operational | 11 years to adulthood | Adolescents can think systematically, can reason about abstract concepts, and can understand ethics and scientific reasoning. | Abstract logic |

The first developmental stage according to Piaget was the sensorimotor stage, the cognitive stage that begins at birth and lasts until around the age of 2. It is defined by the direct physical interactions that babies have with the objects around them. During this stage, babies form their first schemas by using their primary senses—they stare at, listen to, reach for, hold, shake, and taste the things in their environments.

During the sensorimotor stage, babies’ use of their senses to perceive the world is so central to their understanding that whenever babies do not directly perceive objects, as far as they are concerned, the objects do not exist. Piaget found that if he first interested babies in a toy and then covered the toy with a blanket, children who were younger than 6 months of age would act as if the toy had disappeared completely—they never tried to find it under the blanket but would nevertheless smile and reach for it when the blanket was removed. Piaget found that it was not until about 8 months that the children realized that the object was merely covered and not gone. Piaget used the term object permanence to refer to the child’s ability to know that an object exists even when the object cannot be perceived.

At about 2 years of age, and until about 7 years of age, children move into the preoperational stage. During this stage, children begin to use language and to think more abstractly about objects, but their understanding is more intuitive and without much ability to deduce or reason. The thinking is preoperational, meaning that the child lacks the ability to operate on or transform objects mentally. In one study that showed the extent of this inability, Judy DeLoache (1987) showed children a room within a small dollhouse. Inside the room, a small toy was visible behind a small couch. The researchers took the children to another lab room, which was an exact replica of the dollhouse room, but full-sized. When children who were 2.5 years old were asked to find the toy, they did not know where to look—they were simply unable to make the transition across the changes in room size. Three-year-old children, on the other hand, immediately looked for the toy behind the couch, demonstrating that they were improving their operational skills.

The inability of young children to view transitions also leads them to be egocentric—unable to readily see and understand other people’s viewpoints. Developmental psychologists define the theory of mind as the ability to take another person’s viewpoint, and the ability to do so increases rapidly during the preoperational stage. In one demonstration of the development of theory of mind, a researcher shows a child a video of another child (let’s call her Anna) putting a ball in a red box. Then Anna leaves the room, and the video shows that while she is gone, a researcher moves the ball from the red box into a blue box. As the video continues, Anna comes back into the room. The child is then asked to point to the box where Anna will probably look to find her ball. Children who are younger than 4 years of age typically are unable to understand that Anna does not know that the ball has been moved, and they predict that she will look for it in the blue box. After 4 years of age, however, children have developed a theory of mind—they realize that different people can have different viewpoints, and that (although she will be wrong) Anna will nevertheless think that the ball is still in the red box.

After about 7 years of age, the child moves into the concrete operational stage, which is marked by more frequent and more accurate use of transitions, operations, and abstract concepts, including those of time, space, and numbers. An important milestone during the concrete operational stage is the development of conservation—the understanding that changes in the form of an object do not necessarily mean changes in the quantity of the object. Children younger than 7 years generally think that a glass of milk that is tall holds more milk than a glass of milk that is shorter and wider, and they continue to believe this even when they see the same milk poured back and forth between the glasses. It appears that these children focus only on one dimension (in this case, the height of the glass) and ignore the other dimension (width). However, when children reach the concrete operational stage, their abilities to understand such transformations make them aware that, although the milk looks different in the different glasses, the amount must be the same.

At about 11 years of age, children enter the formal operational stage, which is marked by the ability to think in abstract terms and to use scientific and philosophical lines of thought. Children in the formal operational stage are better able to systematically test alternative ideas to determine their influences on outcomes. For instance, rather than haphazardly changing different aspects of a situation that allows no clear conclusions to be drawn, they systematically make changes in one thing at a time and observe what difference that particular change makes. They learn to use deductive reasoning, such as “if this, then that,” and they become capable of imagining situations that “might be,” rather than just those that actually exist.

Piaget’s theories have made a substantial and lasting contribution to developmental psychology. His contributions include the idea that children are not merely passive receptacles of information but rather actively engage in acquiring new knowledge and making sense of the world around them. This general idea has generated many other theories of cognitive development, each designed to help us better understand the development of the child’s information-processing skills (Klahr & McWinney, 1998; Shrager & Siegler, 1998). Furthermore, the extensive research that Piaget’s theory has stimulated has generally supported his beliefs about the order in which cognition develops. Piaget’s work has also been applied in many domains—for instance, many teachers make use of Piaget’s stages to develop educational approaches aimed at the level children are developmentally prepared for (Driscoll, 1994; Levin, Siegler, & Druyan, 1990).

Over the years, Piagetian ideas have been refined. For instance, it is now believed that object permanence develops gradually, rather than more immediately, as a true stage model would predict, and that it can sometimes develop much earlier than Piaget expected. Renée Baillargeon and her colleagues (Baillargeon, 2004; Wang, Baillargeon, & Brueckner, 2004) placed babies in a habituation setup, having them watch as an object was placed behind a screen, entirely hidden from view. The researchers then arranged for the object to reappear from behind another screen in a different place. Babies who saw this pattern of events looked longer at the display than did babies who witnessed the same object physically being moved between the screens. This data suggests that the babies were aware that the object still existed even though it was hidden behind the screen, and thus that they were displaying object permanence as early as 3 months of age, rather than the 8 months that Piaget predicted.

Another factor that might have surprised Piaget is the extent to which a child’s social surroundings influence learning. In some cases, children progress to new ways of thinking and retreat to old ones depending on the type of task they are performing, the circumstances they find themselves in, and the nature of the language used to instruct them (Courage & Howe, 2002). And children in different cultures show somewhat different patterns of cognitive development. Dasen (1972) found that children in non-Western cultures moved to the next developmental stage about a year later than did children from Western cultures and that level of schooling also influenced cognitive development. In short, Piaget’s theory probably understated the contribution of environmental factors to social development.

More recent theories (Cole, 1996; Rogoff, 1990; Tomasello, 1999), based in large part on the sociocultural theory of the Russian scholar Lev Vygotsky (1962, 1978), argue that cognitive development is not isolated entirely within the child but occurs at least in part through social interactions. These scholars argue that children’s thinking develops through constant interactions with more competent others, including parents, peers, and teachers.

An extension of Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory is the idea of community learning, in which children serve as both teachers and learners. This approach is frequently used in classrooms to improve learning as well as to increase responsibility and respect for others. When children work cooperatively together in groups to learn material, they can help and support each other’s learning as well as learn about each other as individuals, thereby reducing prejudice (Aronson, Blaney, Stephan, Sikes, & Snapp, 1978; Brown, 1997).

Aronson, E., Blaney, N., Stephan, C., Sikes, J., & Snapp, M. (1978). The jigsaw classroom. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; Brown, A. L. (1997). Transforming schools into communities of thinking and learning about serious matters. American Psychologist, 52(4), 399–413.

Baillargeon, R. (2004). Infants’ physical world. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13(3), 89–94; Wang, S. H., Baillargeon, R., & Brueckner, L. (2004). Young infants’ reasoning about hidden objects: Evidence from violation-of-expectation tasks with test trials only. Cognition, 93, 167–198.

Cole, M. (1996). Culture in mind. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; Rogoff, B. (1990). Apprenticeship in thinking: Cognitive development in social context. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; Tomasello, M. (1999). The cultural origins of human cognition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Dasen, P. R. (1972). Cross-cultural Piagetian research: A summary. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 3, 23–39.

DeLoache, J. S. (1987). Rapid change in the symbolic functioning of very young children. Science, 238(4833), 1556–1556.

Driscoll, M. P. (1994). Psychology of learning for instruction. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon; Levin, I., Siegler, S. R., & Druyan, S. (1990). Misconceptions on motion: Development and training effects. Child Development, 61, 1544–1556.

Klahr, D., & McWhinney, B. (1998). Information Processing. In D. Kuhn & R. S. Siegler (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Cognition, perception, & language (5th ed., Vol. 2, pp. 631–678). New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; Shrager, J., & Siegler, R. S. (1998). SCADS: A model of children’s strategy choices and strategy discoveries. Psychological Science, 9, 405–422.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1962). Thought and language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Social Development during Childhood

Knowing the Self: The Development of the Self-Concept

One of the important milestones in a child’s social development is learning about his or her own self-existence. This self-awareness is known as consciousness, and the content of consciousness is known as the self-concept. The self-concept is a knowledge representation or schema that contains knowledge about us, including our beliefs about our personality traits, physical characteristics, abilities, values, goals, and roles, as well as the knowledge that we exist as individuals (Kagan, 1991).

Some animals, including chimpanzees, orangutans, and perhaps dolphins, have at least a primitive sense of self (Boysen & Himes, 1999). In one study (Gallup, 1970), researchers painted a red dot on the foreheads of anesthetized chimpanzees and then placed each animal in a cage with a mirror. When the chimps woke up and looked in the mirror, they touched the dot on their faces, not the dot on the faces in the mirror. These actions suggest that the chimps understood that they were looking at themselves and not at other animals, and thus we can assume that they are able to realize that they exist as individuals. On the other hand, most other animals, for example dogs, cats, and monkeys, never realize that it is themselves in the mirror.

Infants who have a similar red dot painted on their foreheads recognize themselves in a mirror in the same way that the chimps do, and they do this by about 18 months of age (Povinelli, Landau, & Perilloux, 1996). The child’s knowledge about the self continues to develop as the child grows. By age 2, the infant becomes aware of his or her sex, as a boy or a girl. By age 4, self-descriptions are likely to be based on physical features, such as hair color and possessions, and by about age 6, the child is able to understand basic emotions and the concepts of traits, being able to make statements such as, “I am a nice person” (Harter, 1998).

Soon after children enter grade school (at about age 5 or 6), they begin to make comparisons with other children, a process known as social comparison. For example, a child might describe himself as being faster than one boy but slower than another (Moretti & Higgins, 1990). According to Erikson, the important component of this process is the development of competence and autonomy—the recognition of one’s own abilities relative to other children. And children increasingly show awareness of social situations—they understand that other people are looking at and judging them the same way that they are looking at and judging others (Doherty, 2009).

Boysen, S. T., & Himes, G. T. (1999). Current issues and emerging theories in animal cognition. Annual Review of Psychology, 50, 683–705.

Doherty, M. J. (2009). Theory of mind: How children understand others’ thoughts and feelings. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Kagan, J. (1991). The theoretical utility of constructs of self. Developmental Review, 11, 244–250.

Moretti, M. M., & Higgins, E. T. (1990). The development of self-esteem vulnerabilities: Social and cognitive factors in developmental psychopathology. In R. J. Sternberg & J. Kolligian, Jr. (Eds.), Competence considered (pp. 286–314). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Povinelli, D. J., Landau, K. R., & Perilloux, H. K. (1996). Self-recognition in young children using delayed versus live feedback: Evidence of a developmental asynchrony. Child Development, 67(4), 1540–1554.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Infancy and Childhood Development-Video

Amanda Rice. (2016, December 6). AP psychology unit 9 infancy and childhood notes part one by Mrs. Rice. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KOwBBuuzEIc. Standard YouTube License.

Summary

Infants are born with a number of behaviors that help them protect themselves, as well as grow and develop. Jean Piaget’s stage model of cognitive development posits that children gain their cognitive ability in a developmental order, i.e., that children at different ages think in fundamentally different ways. His stage model of cognitive development proposes that children learn through assimilation and accommodation and that cognitive development follows specific sequential stages: sensorimotor, preoperational, concrete operational, and formal operational. Children use assimilation, which is the use of an already developed schema to understand new information and accommodation, which is the change of an existing schema on the basis of new information, to incorporate and integrate new knowledge with what they already know. Children develop schemas, defined as patterns of knowledge in long-term memory, which help them remember, organize, and respond to information. In contrast to Piaget’s thinking, children can advance through stages more rapidly, and may use different stage-behaviors under different circumstances.