Learning

Introduction

Birds build nests and migrate as winter approaches. Infants suckle at their mother’s breast. Dogs shake water off wet fur. Salmon swim upstream to spawn, and spiders spin intricate webs. What do these seemingly unrelated behaviors have in common? They all are unlearned behaviors. Both instincts and reflexes are innate behaviors that organisms are born with. Reflexes are a motor or neural reaction to a specific stimulus in the environment. They tend to be simpler than instincts, involve the activity of specific body parts and systems (e.g., the knee-jerk reflex and the contraction of the pupil in bright light), and involve more primitive centers of the central nervous system (e.g., the spinal cord and the medulla). In contrast, instincts are innate behaviors that are triggered by a broader range of events, such as aging and the change of seasons. They are more complex patterns of behavior, involve movement of the organism as a whole (e.g., sexual activity and migration), and involve higher brain centers.

Both reflexes and instincts help an organism adapt to its environment and do not have to be learned. For example, every healthy human baby has a sucking reflex, present at birth. Babies are born knowing how to suck on a nipple, whether artificial (from a bottle) or human. Nobody teaches the baby to suck, just as no one teaches a sea turtle hatchling to move toward the ocean. Learning, like reflexes and instincts, allows an organism to adapt to its environment. But unlike instincts and reflexes, learned behaviors involve change and experience: learning is a relatively permanent change in behavior or knowledge that results from experience. In contrast to the innate behaviors discussed above, learning involves acquiring knowledge and skills through experience. For example, learning to surf, as well as any complex learning process (e.g., learning about the discipline of psychology), involves a complex interaction of conscious and unconscious processes. Learning has traditionally been studied in terms of its simplest components—the associations our minds automatically make between events. Our minds have a natural tendency to connect events that occur closely together or in sequence.

OpenStax. (2016, October 31). Psychology. OpenStax Psychology. Retrieved from https://cnx.org/contents/Sr8Ev5Og@5.52:b7opmCF3@6/Stages-of-Development#Figure_09_02_Stages. Licensed under CC BY-4.0.

Learning

What do you do when studying for an exam? Do you read your class notes and textbook (hopefully not for the very first time)? Do you try to find a quiet place without distraction? Do you use flash cards to test your knowledge? The choices you make reveal your theory of learning, but there is no reason for you to limit yourself to your own intuitions. There is a vast and vibrant science of learning, in which researchers from psychology, education, and neuroscience study basic principles of learning and memory. When you study for a test, you incorporate your past knowledge into learning this new knowledge. That is, depending on your previous experiences, you will “learn” the material in different ways.

“Student Studying” by UBC Learning Commons. Retrieved from https://www.flickr.com/photos/56866338@N06/8726823600/. Licensed under CC BY-2.0.

In fact, learning is a much broader domain than you might think. Consider: Is listening to music a form of learning? More often, it seems listening to music is a way of avoiding learning. But we know that your brain’s response to auditory information changes with your experience with that information, a form of learning called auditory perceptual learning (Polley, Steinberg, & Merzenich, 2006). Each time we listen to a song, we hear it differently because of our experience. When we exhibit changes in behavior without having intended to learn something, that is called implicit learning (Seger, 1994), and when we exhibit changes in our behavior that reveal the influence of past experience even though we are not attempting to use that experience, that is called implicit memory (Richardson-Klavehn & Bjork, 1988).

Other well-studied forms of learning include the types of learning that are general across species. We can’t ask a slug to learn a poem or a lemur to learn to bat left-handed, but we can assess learning in other ways. For example, we can look for a change in our responses to things when we are repeatedly stimulated. If you live in a house with a grandfather clock, you know that what was once an annoying and intrusive sound is now probably barely audible to you. Similarly, poking an earthworm again and again is likely to lead to a reduction in its retraction from your touch. These phenomena are forms of nonassociative learning, in which single repeated exposure leads to a change in behavior (Pinsker, Kupfermann, Castelluci, & Kandel, 1970). When our response lessens with exposure, it is called habituation, and when it increases (like it might with a particularly annoying laugh), it is called sensitization.

Animals can also learn about relationships between things, such as when an alley cat learns that the sound of janitors working in a restaurant precedes the dumping of delicious new garbage (an example of stimulus-stimulus learning called classical conditioning), or when a dog learns to roll over to get a treat (a form of stimulus-response learning called operant conditioning).

Here, we’ll review some of the conditions that affect learning, with an eye toward the type of explicit learning we do when trying to learn something. Jenkins (1979) classified experiments on learning and memory into four groups of factors (renamed here): learners, encoding activities, materials, and retrieval.

Benjamin, A. (2018). Factors influencing learning. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. DOI: nobaproject.com. Retrieved from http://nobaproject.com/modules/factors-influencing-learning. Licensed under CC BY-SA-4.0.

Learners

People bring numerous individual differences with them into memory experiments, and many of these variables affect learning. In the classroom, motivation matters (Pintrich, 2003), though experimental attempts to induce motivation with money yield only modest benefits (Heyer & O’Kelly, 1949). Learners are, however; quite able to allocate more effort to learning prioritized over unimportant materials (Castel, Benjamin, Craik, & Watkins, 2002).

In addition, the organization and planning skills that a learner exhibits matter a lot (Garavalia & Gredler, 2002), suggesting that the efficiency with which one organizes self-guided learning is an important component of learning. Research attests that we can hold between 5 and 9 individual pieces of information in our working memory at once. This is partly why in the 1950s, Bell Labs developed a 7-digit phone number system.

“Ericsson Dialog in Green” by Diamondmagna. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ericsson_Dialog_in_green.JPG. Licensed under CC BY-SA-4.0.

One well-studied and important variable is working memory capacity. Working memory describes the form of memory we use to hold onto information temporarily. Working memory is used, for example, to keep track of where we are in the course of a complicated math problem, and what the relevant outcomes of prior steps in that problem are. Higher scores on working memory measures are predictive of better reasoning skills (Kyllonen & Christal, 1990), reading comprehension (Daneman & Carpenter, 1980), and even better control of attention (Kane, Conway, Hambrick, & Engle, 2008).

Anxiety also affects the quality of learning. For example, people with math anxiety have a smaller capacity for remembering math-related information in working memory, such as the results of carrying a digit in arithmetic (Ashcraft & Kirk, 2001). Having students write about their specific anxiety seems to reduce the worry associated with tests and increases performance on math tests (Ramirez & Beilock, 2011).

One good place to end this discussion is to consider the role of expertise. Though there probably is a finite capacity on our ability to store information (Landauer, 1986), in practice, this concept is misleading. In fact, because the usual bottleneck to remembering something is our ability to access information, not our space to store it, having more knowledge or expertise actually enhances our ability to learn new information. A classic example can be seen in comparing a chess master with a chess novice on their ability to learn and remember the positions of pieces on a chessboard (Chase & Simon, 1973). In that experiment, the master remembered the location of many more pieces than the novice, even after only a very short glance. Maybe chess masters are just smarter than the average chess beginner, and have better memory? No. The advantage the expert exhibited only was apparent when the pieces were arranged in a plausible format for an ongoing chess game; when the pieces were placed randomly, both groups did equivalently poorly. Expertise allowed the master to chunk (Simon, 1974) multiple pieces into a smaller number of pieces of information—but only when that information was structured in such a way so as to allow the application of that expertise.

Benjamin, A. (2018). Factors influencing learning. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. DOI: nobaproject.com. Retrieved from http://nobaproject.com/modules/factors-influencing-learning. Licensed under CC BY-SA-4.0.

Encoding Activities

What we do when we’re learning is very important. We’ve all had the experience of reading something and suddenly coming to the realization that we don’t remember a single thing, even the sentence that we just read. How we go about encoding information determines a lot about how much we remember. You might think that the most important thing is to try to learn. Interestingly, this is not true, at least not completely. Trying to learn a list of words, as compared to just evaluating each word for its part of speech (i.e., noun, verb, adjective) does help you recall the words—that is, it helps you remember and write down more of the words later. But it actually impairs your ability to recognize the words—to judge on a later list which words are the ones that you studied (Eagle & Leiter, 1964). So this is a case in which incidental learning—that is, learning without the intention to learn—is better than intentional learning.

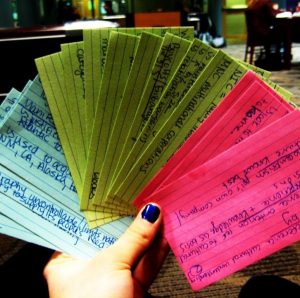

Motivation to learn doesn’t make much of a difference unless learners use effective strategies for encoding the information they want to retain. Although they’re not flashy, methods like spaced practice, interleaving, and frequent testing are among the most effective ways to apply your efforts.

Retrieved from https://www.flickr.com/photos/cali4beach/5428974972/. Licensed under CC BY-2.0.

Such examples are not particularly rare and are not limited to recognition. Nairne, Pandeirada, and Thompson (2008) showed, for example, that survival processing—thinking about and rating each word in a list for its relevance in a survival scenario—led to much higher recall than intentional learning (and also higher, in fact, than other encoding activities that are also known to lead to high levels of recall). Clearly, merely intending to learn something is not enough. How a learner actively processes the material plays a large role; for example, reading words and evaluating their meaning leads to better learning than reading them and evaluating the way that the words look or sound (Craik & Lockhart, 1972). These results suggest that individual differences in motivation will not have a large effect on learning unless learners also have accurate ideas about how to effectively learn material when they care to do so.

So, do learners know how to effectively encode material? People allowed to freely allocate their time to study a list of words do remember those words better than a group that doesn’t have control over their own study time, though the advantage is relatively small and is limited to the subset of learners who choose to spend more time on the more difficult material (Tullis & Benjamin, 2011). In addition, learners who have an opportunity to review materials that they select for restudy often learn more than another group that is asked to restudy the materials that they didn’t select for restudy (Kornell & Metcalfe, 2006). However, this advantage also appears to be relatively modest (Kimball, Smith, & Muntean, 2012) and wasn’t apparent in a group of older learners (Tullis & Benjamin, 2012). Taken together, all of the evidence seems to support the claim that self-control of learning can be effective, but only when learners have good ideas about what an effective learning strategy is.

One factor that appears to have a big effect and that learners do not always appear to understand is the effect of scheduling repetitions of study. If you are studying for a final exam next week and plan to spend a total of five hours, what is the best way to distribute your study? The evidence is clear that spacing one’s repetitions apart in time is superior than massing them all together (Baddeley & Longman, 1978; Bahrick, Bahrick, Bahrick, & Bahrick, 1993; Melton, 1967). Increasing the spacing between consecutive presentations appears to benefit learning yet further (Landauer & Bjork, 1978). A similar advantage is evident for the practice of interleaving multiple skills to be learned: For example, baseball batters improved more when they faced a mix of different types of pitches than when they faced the same pitches blocked by type (Hall, Domingues, & Cavazos, 1994). Students also showed better performance on a test when different types of mathematics problems were interleaved rather than blocked during learning (Taylor & Rohrer, 2010).

One final factor that merits discussion is the role of testing. Educators and students often think about testing as a way of assessing knowledge, and this is indeed an important use of tests. But tests themselves affect memory, because retrieval is one of the most powerful ways of enhancing learning (Roediger & Butler, 2013). Self-testing is an underutilized and potent means of making learning more durable.

Benjamin, A. (2018). Factors influencing learning. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. DOI: nobaproject.com. Retrieved from http://nobaproject.com/modules/factors-influencing-learning. Licensed under CC BY-SA-4.0.

General Principles of Learning

We’ve only begun to scratch the surface here of the many variables that affect the quality and content of learning (Mullin, Herrmann, & Searleman, 1993). But even within this brief examination of the differences between people and the activities they engage in, we can see some basic principles of the learning process. To be able to guide our own learning effectively, we must be able to evaluate the progress of our learning accurately and choose activities that enhance learning efficiently. It is of little use to study for a long time if a student cannot discern between what material she has or has not mastered, and if additional study activities move her no closer to mastery. Metacognition describes the knowledge and skills people have in monitoring and controlling their own learning and memory. We can work to acquire better metacognition by paying attention to our successes and failures in estimating what we do and don’t know, and by using testing often to monitor our progress.

Sometimes, it doesn’t make sense to talk about whether a particular encoding activity is good or bad for learning. Rather, we can talk about whether that activity is good for learning as revealed by a particular test. For example, although reading words for meaning leads to better performance on a test of recall or recognition than paying attention to the pronunciation of the word, it leads to worse performance on a test that taps knowledge of that pronunciation, such as whether a previously studied word rhymes with another word (Morris, Bransford, & Franks, 1977). The principle of transfer-appropriate processing states that memory is “better” when the test taps the same type of knowledge as the original encoding activity. When thinking about how to learn material, we should always be thinking about the situations in which we are likely to need access to that material. An emergency responder who needs access to learned procedures under conditions of great stress should learn differently from a hobbyist learning to use a new digital camera.

In order to not forget things, we employ a variety of tricks (like scribbling a quick note on your hand). However, if we were unable to forget information, it would interfere with learning new or contradictory material.

Retrieved from https://www.flickr.com/photos/39609980@N00/1525442181/. Licensed under CC BY-NC-2.0.

Forgetting is sometimes seen as the enemy of learning, but, in fact, forgetting is a highly desirable part of the learning process. The main bottleneck we face in using our knowledge is being able to access it. We have all had the experience of retrieval failure—that is, not being able to remember a piece of information that we know we have, and that we can access easily once the right set of cues is provided. Because access is difficult, it is important to jettison information that is not needed—that is, to forget it. Without forgetting, our minds would become cluttered with out-of-date or irrelevant information. And, just imagine how complicated life would be if we were unable to forget the names of past acquaintances, teachers, or romantic partners.

But the value of forgetting is even greater than that. There is lots of evidence that some forgetting is a prerequisite for more learning. For example, the previously discussed benefits of distributing practice opportunities may arise in part because of the greater forgetting that takes places between those spaced learning events. It is for this reason that some encoding activities that are difficult and lead to the appearance of slow learning actually lead to superior learning in the long run (Bjork, 2011). When we opt for learning activities that enhance learning quickly, we must be aware that these are not always the same techniques that lead to durable, long-term learning.

Benjamin, A. (2018). Factors influencing learning. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. DOI: nobaproject.com. Retrieved from http://nobaproject.com/modules/factors-influencing-learning. Licensed under CC BY-SA-4.0.

Learning-Video

Kintal Shah. (2016, May 16). Cognitive processes in learning types, definition & examples video & lesson transcript study. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cohUMmVkipA. Standard YouTube License.

The Learning Scientists. (2016, September 25). Study strategies: Interleaving. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kV64Bu6sec0. Standard YouTube License.

The Learning Scientists. (2016, September 19). Study strategies: Spaced practice. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3WJYp98eys8. Standard YouTube License.

The Learning Scientists. (2016, September 19). Study strategies: Retrieval practice. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pjrqc6UMDKM. Standard YouTube License.

Summary

Learning is the relatively permanent change in knowledge or behavior that is the result of experience. Without the ability to learn from our experiences, our lives would be remarkably dangerous and inefficient. Let’s think back to the questions we began the module with. What might you now do differently when preparing for an exam? Hopefully, you will think about testing yourself frequently, developing an accurate sense of what you do and do not know, how you are likely to use the knowledge, and using the scheduling of tasks to your advantage. If you are learning a new skill or new material, using the scientific study of learning as a basis for the study and practice decisions you make is a good bet.

Benjamin, A. (2018). Factors influencing learning. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. DOI: nobaproject.com. Retrieved from http://nobaproject.com/modules/factors-influencing-learning. Licensed under CC BY-SA-4.0.