Memory and Cognition

Introduction

Memory and cognition represent the two major interests of cognitive psychologists. Memory is defined as the ability to store and retrieve information over time, and cognition is defined as the processes of acquiring and using knowledge. The cognitive approach became the most important school of psychology during the 1960s, and the field of psychology has remained in large part, cognitive since that time. The cognitive school was influenced in large part by the development of the electronic computer, and although the differences between computers and the human mind are vast, cognitive psychologists have used the computer as a model for understanding the workings of the mind. Our memories allow us to do relatively simple things, such as remembering where we parked our car or the name of the current president of the United States, but also allow us to form complex memories, such as how to ride a bicycle or how to write a computer program. Moreover, our memories define us as individuals—they are our experiences, our relationships, our successes, and our failures.

At least for some things, our memory is very good (Bahrick, 2000). Once we learn a face, we can recognize that face many years later. We know the lyrics of many songs by heart, and we can give definitions for tens of thousands of words. Mitchell (2006) contacted participants 17 years after they had been briefly exposed to some line drawings in a lab and found that they still could identify the images significantly better than participants who had never seen them.

For some people, memory is truly amazing. Consider, for instance, the case of Kim Peek, who was the inspiration for the Academy Award–winning film Rain Man. Although Peek’s IQ was only 87, significantly below the average of about 100, it is estimated that he memorized more than 10,000 books in his lifetime (Wisconsin Medical Society, n.d.; “Kim Peek,” 2004). The Russian psychologist A. R. Luria (2004) has described the abilities of a man known as “S,” who seems to have unlimited memory. S remembers strings of hundreds of random letters for years at a time, and seems in fact to never forget anything.

Memory and Cognition

Memory Types

Explicit Memory

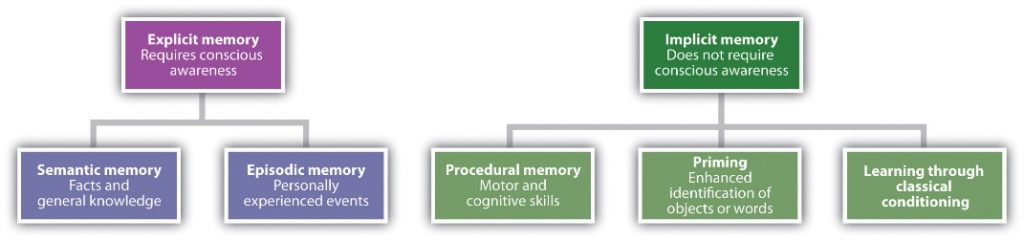

Psychologists conceptualize memory in terms of types, in terms of stages, and in terms of processes. When we assess memory by asking a person to consciously remember things, we are measuring explicit memory. Explicit memory refers to knowledge or experiences that can be consciously remembered.

There are two types of explicit memory: episodic and semantic. Episodic memory refers to the firsthand experiences that we have had (e.g., recollections of our high school graduation day or of the fantastic dinner we had in New York last year). Semantic memory refers to our knowledge of facts and concepts about the world (e.g., that the absolute value of −90 is greater than the absolute value of 9 and that one definition of the word “affect” is “the experience of feeling or emotion”).

Exmory is assessed using measurein which the individual being tested must consciously attempt to remember the information. A recall memory test is a measure of explicit memory that involves recalling information from memory that has previously been remembered. We rely on our recall memory when we take an essay test, because the test requires us to generate previously remembered information. A multiple-choice test is an example of a recognition memory test, a measure of explicit memory that involves determining whether information has been seen or learned before.

Your own experiences taking tests will probably lead you to agree with the scientific research finding that recall is more difficult than recognition. Recall, which is often required on essay tests, involves two steps: first generating an answer and then determining whether it seems to be the correct one. Recognition, as on multiple-choice tests, only involves determining which item from a list seems most correct (Haist, Shimamura, & Squire, 1992). Although they involve different processes, recall and recognition memory measures tend to be correlated. Students who do better on a multiple-choice exams will also, by and large, do better on an essay exam (Bridgeman & Morgan, 1996).

A third way of measuring memory is known as relearning (Nelson, 1985). Measures of relearning (or savings) assess how much more quickly information is processed or learned when it is studied again after it has already been learned but then forgotten. If you have taken some French courses in the past, for instance, you might have forgotten most of the vocabulary you learned. But if you were to work on your French again, you’d learn the vocabulary much faster the second time around. Relearning can be a more sensitive measure of memory than either recall or recognition because it allows assessing memory in terms of “how much” or “how fast” rather than simply “correct” versus “incorrect” responses. Relearning also allows us to measure memory for procedures like driving a car or playing a piano piece, as well as memory for facts and figures.

Implicit Memory

While explicit memory consists of the things that we can consciously report that we know, implicit memory refers to knowledge that we cannot consciously access. However, implicit memory is nevertheless exceedingly important to us because it has a direct effect on our behavior. Implicit memory refers to the influence of experience on behavior, even if the individual is not aware of those influences. There are three general types of implicit memory: procedural memory, classical conditioning effects, and priming.

Procedural memory refers to our often unexplainable knowledge of how to do things. When we walk from one place to another, speak to another person in English, dial a cell phone, or play a video game, we are using procedural memory. Procedural memory allows us to perform complex tasks, even though we may not be able to explain to others how we do them. There is no way to tell someone how to ride a bicycle; a person has to learn by doing it. The idea of implicit memory helps explain how infants are able to learn. The ability to crawl, walk, and talk are procedures, and these skills are easily and efficiently developed while we are children despite the fact that as adults we have no conscious memory of having learned them.

A second type of implicit memory is classical conditioning effects, in which we learn, often without effort or awareness, to associate neutral stimuli (such as a sound or a light) with another stimulus (such as food), which creates a naturally occurring response, such as enjoyment or salivation. The memory for the association is demonstrated when the conditioned stimulus (the sound) begins to create the same response as the unconditioned stimulus (the food) did before the learning.

The final type of implicit memory is known as priming, or changes in behavior as a result of experiences that have happened frequently or recently. Priming refers both to the activation of knowledge (e.g., we can prime the concept of “kindness” by presenting people with words related to kindness) and to the influence of that activation on behavior (people who are primed with the concept of kindness may act more kindly). One measure of the influence of priming on implicit memory is the word fragment test, in which a person is asked to fill in missing letters to make words. You can try this yourself: First, try to complete the following word fragments, but work on each one for only 3 or 4 seconds. Do any words pop into mind quickly?

_ i b _ a _ y

_ h _ s _ _ i _ n

_ o _ k

_ h _ i s _

Now read the following sentence carefully:

“He got his materials from the shelves, checked them out, and then left the building.”

Then try again to make words out of the word fragments.

I think you might find that it is easier to complete fragments 1 and 3 as “library” and “book,” respectively, after you read the sentence than it was before you read it. However, reading the sentence didn’t really help you to complete fragments 2 and 4 as “physician” and “chaise.” This difference in implicit memory probably occurred because as you read the sentence, the concept of “library” (and perhaps “book”) was primed, even though they were never mentioned explicitly. Once a concept is primed it influences our behaviors, for instance, on word fragment tests.

Although priming may not seem like a very important type of memory, it has a profound impact on our everyday lives. Many of our everyday behaviors occur when the situations around us prime cognitions and emotions (Schröder & Thagard, 2012). Seeing an advertisement for cigarettes may influence our decision to start smoking, seeing the flag of our home country may arouse our patriotism, and seeing a student from a rival school may arouse our competitive spirit. And these influences on our behaviors may occur entirely without our awareness.

Atkinson, R. C., & Shiffrin, R. M. (1968). Human memory: A proposed system and its control processes. In K. Spence (Ed.), The psychology of learning and motivation (Vol. 2). Oxford, England: Academic Press.

Bridgeman, B., & Morgan, R. (1996). Success in college for students with discrepancies between performance on multiple-choice and essay tests. Journal of Educational Psychology, 88(2), 333–340.

Haist, F., Shimamura, A. P., & Squire, L. R. (1992). On the relationship between recall and recognition memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 18(4), 691–702.

Nelson, T. O. (1985). Ebbinghaus’s contribution to the measurement of retention: Savings during relearning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 11(3), 472–478.

Schröder, T., & Thagard, P. (2012). The affective meanings of automatic social behaviors: Three mechanisms that explain priming. Psychological Review. doi:10.1037/a0030972↑

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Stages of Memory

Another way of understanding memory is to think about it in terms of stages that describe the length of time that information remains available to us. According to this approach, information begins in sensory memory, moves to short-term memory, and eventually moves to long-term memory. But not all information makes it through all three stages; most of it is forgotten. Whether the information moves from shorter-duration memory into longer-duration memory, or whether it is lost from memory entirely, depends on how the information is attended to and processed.

Sensory Memory

Sensory memory refers to the brief storage of sensory information. Sensory memory is a memory buffer that lasts very briefly and then, unless it is attended to and passed on for more processing, is forgotten. The purpose of sensory memory is to give the brain some time to process the incoming sensations and to allow us to see the world as an unbroken stream of events rather than as individual pieces. Visual sensory memory is known as iconic memory. Iconic memory was first studied by the psychologist George Sperling (1960). In his research, Sperling showed participants a display of letters in rows; however, the display lasted only about 50 milliseconds (1/20 of a second). Then, Sperling gave his participants a recall test in which they were asked to name all the letters that they could remember. On average, the participants could remember only about one-quarter of the letters that they had seen.

Sperling reasoned that the participants had seen all the letters but could remember them only very briefly, making it impossible for them to report them all. To test this idea, in his next experiment he first showed the same letters, but then

after the display had been removed, he signaled to the participants to report the letters from either the first, second, or third row. In this condition, the participants now reported almost all the letters in that row. This finding confirmed Sperling’s hunch: Participants had access to all of the letters in their iconic memories, and if the task was short enough, they were able to report on the part of the display he asked them to. The “short enough” is the length of iconic memory, which turns out to be about 250 milliseconds (¼ of a second).

Auditory sensory memory is known as echoic memory. In contrast to iconic memories, which decay very rapidly, echoic memories can last as long as 4 seconds (Cowan, Lichty, & Grove, 1990). This is convenient as it allows you—among other things—to remember the words that you said at the beginning of a long sentence when you get to the end of it, and to take notes on your psychology professor’s most recent statement even after he or she has finished saying it.

In some people, iconic memory seems to last longer, a phenomenon known as eidetic imagery (or “photographic memory”) in which people can report details of an image over long periods of time. These people, who often suffer from psychological disorders such as autism spectrum disorder, claim that they can “see” an image long after it has been presented and can often report accurately on that image. There is also some evidence for eidetic memories in hearing; some people report that their echoic memories persist for unusually long periods of time. The composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart may have possessed eidetic memory for music, because even when he was very young and had not yet had a great deal of musical training, he could listen to long compositions and then play them back almost perfectly (Solomon, 1995).

Short-Term Memory

Most of the information that gets into sensory memory is forgotten, but information that we turn our attention to, with the goal of remembering it, may pass into short-term memory. Short-term memory (STM) is the place where small amounts of information can be temporarily kept for more than a few seconds but usually for less than one minute (Baddeley, Vallar, & Shallice, 1990). Information in short-term memory is not stored permanently but rather becomes available for us to process, and the processes that we use to make sense of, modify, interpret, and store information in STM are known as working memory. Although it is called “memory,” working memory is not a storage of memory like STM, but rather a set of memory procedures or operations.

Short-term memory is limited in both the length and the amount of information it can hold. Peterson and Peterson (1959) found that when people were asked to remember a list of three-letter strings and then were immediately asked to perform a distracting task (counting backward by threes), the material was quickly forgotten, such that by 18 seconds it was virtually gone.

One way to prevent the decay of information from short-term memory is to use working memory to rehearse it.

Maintenance rehearsal is the process of repeating information mentally or out loud with the goal of keeping it in memory. We engage in maintenance rehearsal to keep a something that we want to remember (e.g., a person’s name, e-mail address, or phone number) in mind long enough to write it down, use it, or potentially transfer it to long-term memory. If we continue to rehearse information it will stay in STM until we stop rehearsing it, but there is also a capacity limit to STM. Try reading each of the following rows of numbers, one row at a time, at a rate of about one number each second. Then when you have finished each row, close your eyes and write down as many of the numbers as you can remember.

019

3586

10295

861059

1029384

75674834

657874104

6550423897

If you are like the average person, you will have found that on this test of working memory, known as a digit span test, you did pretty well up to about the fourth line, and then you started having trouble. I bet you missed some of the numbers in the last three rows, and did pretty poorly on the last one.

The digit span of most adults is between five and nine digits, with an average of about seven. The cognitive psychologist George Miller (1956) referred to “seven plus or minus two” pieces of information as the “magic number” in short-term memory. But if we can only hold a maximum of about nine digits in short-term memory, then how can we remember larger amounts of information than this? For instance, how can we ever remember a 10-digit phone number long enough to dial it?

If information makes it past short term-memory it may enter long-term memory (LTM), memory storage that can hold information for days, months, and years. The capacity of long-term memory is large, and there is no known limit to what we can remember (Wang, Liu, & Wang, 2003). Although, we may forget at least some information after we learn it, other things will stay with us forever.

Baddeley, A. D., Vallar, G., & Shallice, T. (1990). The development of the concept of working memory: Implications and contributions of neuropsychology. In G. Vallar & T. Shallice (Eds.), Neuropsychological impairments of short-term memory (pp. 54–73). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Cowan, N., Lichty, W., & Grove, T. R. (1990). Properties of memory for unattended spoken syllables. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 16(2), 258–268.

Didierjean, A., & Marmèche, E. (2005). Anticipatory representation of visual basketball scenes by novice and expert players. Visual Cognition, 12(2), 265–283.

Miller, G. A. (1956). The magical number seven, plus or minus two: Some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychological Review, 63(2), 81–97.

Peterson, L., & Peterson, M. J. (1959). Short-term retention of individual verbal items. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 58(3), 193–198.

Simon, H. A., & Chase, W. G. (1973). Skill in chess. American Scientist, 61(4), 394–403.

Sperling, G. (1960). The information available in brief visual presentation. Psychological Monographs, 74(11), 1–29.

Solomon, M. (1995). Mozart: A life. New York, NY: Harper Perennial.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Unsworth, N., & Engle, R. W. (2007). On the division of short-term and working memory: An examination of simple and complex span and their relation to higher order abilities. Psychological Bulletin, 133(6), 1038–1066.

Wang, Y., Liu, D., & Wang, Y. (2003). Discovering the capacity of human memory. Brain & Mind, 4(2), 189–198.

Memory and Cognition-Video

CrashCourse (2014, May14). How we make memories-Crash Course Psychology #13. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bSycdIx-C48Standard YouTube License.

Granby High School AP Psychology. (2015, September 23). Introduction to memory. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GL6xSLbTw_c. Standard YouTube License.As we learned in this section, memory and cognition are the two major interests of cognitive psychologists. The cognitive school was influenced in large part by the development of the electronic computer. Psychologists conceptualize memory in terms of types, stages, and processes. Explicit memory is assessed using measures in which the individual being tested must consciously attempt to remember the information. Explicit memory includes semantic and episodic memory. Explicit memory tests include recall memory tests, recognition memory tests, and measures of relearning (also known as savings).

Implicit memory refers to the influence of experience on behavior, even if the individual is not aware of those influences. Implicit memory is made up of procedural memory, classical conditioning effects, and priming. Priming refers both to the activation of knowledge and to the influence of that activation on behavior. An important characteristic of implicit memories is that they are frequently formed and used automatically, without much effort or awareness on our part.

Sensory memory, including iconic and echoic memory, is a memory buffer that lasts only very briefly and then, unless it is attended to and passed on for more processing, is forgotten. Information that we turn our attention to may move into short-term memory (STM). STM is limited in both the length and the amount of information it can hold. Working memory is a set of memory procedures or operations that operates on the information in STM. Working memory’s central executive directs the strategies used to keep information in STM, such as maintenance rehearsal, visualization, and chunking.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.