Psychology as a Science

Introduction

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. The word “psychology” comes from the Greek words “psyche,” meaning life, and “logos,” meaning explanation. Psychology is a popular major for students, a popular topic in the public media, and a part of our everyday lives. Television shows such as Dr. Phil feature psychologists who provide personal advice to those with personal or family difficulties. Crime dramas such as CSI, Bones, Dexter, and others feature the work of forensic psychologists who use psychological principles to help solve crimes. And many people have direct knowledge about psychology because they have visited psychologists, for instance, school counselors, family therapists, and religious, marriage, or bereavement counselors.

Because we are frequently exposed to the work of psychologists in our everyday lives, we all have an idea about what psychology is and what psychologists do. In many ways I am sure that your conceptions are correct. Psychologists do work in forensic fields, and they do provide counseling and therapy for people in distress. But there are hundreds of thousands of psychologists around the world, working together to learn about human behavior and to help people who are in psychological distress cope with their difficulties. Psychology is a fast-growing global effort which aims to understand how people think and act, and to create a better world for all of us.

This section provides an introduction to the broad field of psychology and the many approaches that psychologists take to understanding human behavior. We will consider how psychologists conduct scientific research, with an overview of some of the most important approaches used and topics studied by psychologists, and also consider the variety of fields in which psychologists work. I expect that you may find that at least some of your preconceptions about psychology will be challenged and changed, and you will learn that psychology is a field that will provide you with new ways of thinking about your own thoughts, feelings, and actions.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Psychology as a Science

Despite the differences in their interests, areas of study, and approaches, all psychologists have one thing in common: They rely on scientific methods. Research psychologists use scientific methods to create new knowledge about the causes of behavior, whereas psychologist-practitioners, such as clinical, counseling, industrial-organizational, and school psychologists, use existing research to enhance the everyday lives of others. The science of psychology is important for both researchers and practitioners.

In a sense, all humans are scientists. We all have an interest in asking and answering questions about our world. We want to know why things happen, when and if they are likely to happen again, and how to reproduce or change them. Such knowledge enables us to predict our own behavior and that of others. We may even collect data (i.e., any information collected through formal observation or measurement) to aid us in this undertaking. It has been argued that people are “everyday scientists” who conduct research projects to answer questions about behavior (Nisbett & Ross, 1980).

When we perform poorly on an important test, we try to understand what caused our failure to remember or understand the material and what might help us do better the next time. When our good friends Monisha and Charlie break up, despite the fact that they appeared to have a relationship made in heaven, we try to determine what happened. When we contemplate the rise of terrorist acts around the world, we try to investigate the causes of this problem by looking at the terrorists themselves, the situation around them, and others’ responses to them.

The Problem of Intuition

The results of these “everyday” research projects can teach us many principles of human behavior. We learn through experience that if we give someone bad news, he or she may blame us even though the news was not our fault. We learn that people may become depressed after they fail at an important task. We see that aggressive behavior occurs frequently in our society, and we develop theories to explain why this is so. These insights are part of everyday social life.

The problem, however; with the way people collect and interpret data in their everyday lives is that they are not always particularly thorough. Often, when one explanation for an event seems “right,” we adopt that explanation as the truth even when other explanations are possible and potentially more accurate. For example, eyewitnesses to violent crimes are often extremely confident in their identifications of the perpetrators of these crimes. But scientific research finds that eyewitnesses are no less confident in their identifications when they are incorrect than when they are correct (Cutler & Wells, 2009; Wells & Hasel, 2008).

People may also become convinced of the existence of extrasensory perception (ESP), or the predictive value of astrology, when there is no actual evidence for either (Gilovich, 1993). Furthermore, psychologists have also found that there are a variety of cognitive and motivational biases that frequently influence our perceptions and lead us to draw erroneous conclusions (Fiske & Taylor, 2007; Hsee & Hastie, 2006). In summary, accepting explanations for events without testing them thoroughly may lead us to think that we know the causes of things when we really do not. The critical thinking skills that you learn as you study psychology will help you critically evaluate evidence to draw valid conclusions.

Once we learn about the outcome of a given event (e.g., when we read about the results of a research project), we frequently believe that we would have been able to predict the outcome ahead of time. For instance, if half of a class of students is told that research concerning attraction between people has demonstrated that “opposites attract” and the other half is told that research has demonstrated that “birds of a feather flock together,” most of the students will report believing that the outcome that they just read about is true, and that they would have predicted the outcome before they had read about it. Of course, both of these contradictory outcomes cannot be true. (In fact, psychological research finds that “birds of a feather flock together” is generally the case.) The problem is that just reading a description of research findings leads us to think of the many cases we know that support the findings, and thus makes them seem believable.

The tendency to think that we could have predicted something that has already occurred that we probably would not have been able to predict is called the hindsight bias, and many people in many different places succumb to it (Roese & Vohs, 2012). Medical doctors, as an example, often do not learn from prior cases that they are required to study, because once they hear the correct answer, they think that they would easily have been able to make the correct diagnosis (Arkes, 2013). And jurors are likely to judge people who made bad decisions harshly because they erroneously think that the person should have been able to see the negative outcome ahead of time (Fleischhut, Meder, & Gigerenzer, 2017). The hindsight bias creates overconfidence, leading us to be more confident that we know things than we really are.

Why Psychologists Rely on Empirical Methods

All scientists, whether they are physicists, chemists, biologists, sociologists, or psychologists, use empirical methods to study the topics that interest them. Empirical methods include the processes of collecting and organizing data and drawing conclusions about those data. The empirical methods used by scientists have developed over many years and provide a basis for collecting, analyzing, and interpreting data within a common framework in which information can be shared. We can label the scientific method as the set of assumptions, rules, and procedures that scientists use to conduct empirical research.

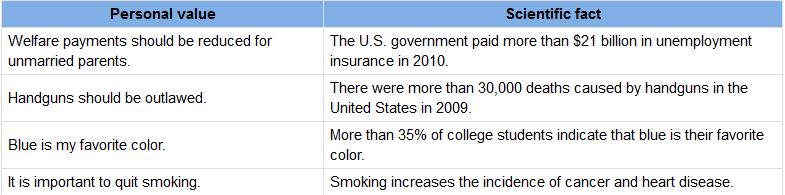

Although scientific research is an important method of studying human behavior, not all questions can be answered using scientific approaches. Statements that cannot be objectively measured or objectively determined to be true or false are not within the domain of scientific inquiry. Scientists therefore draw a distinction between values and facts. Values are personal statements such as “Abortion should not be permitted in this country,” “I will go to heaven when I die,” or “It is important to study psychology.” Facts are objective statements determined to be accurate through empirical study. Examples are “There were more than 21,000 homicides in the United States in 2009,” or “Research demonstrates that individuals who are exposed to highly stressful situations over long periods of time develop more health problems than those who are not.”

Because values cannot be considered to be either true or false, science cannot prove or disprove them. Nevertheless, research can sometimes provide facts that can help people develop their values. For instance, science may be able to objectively measure the impact of unwanted children on a society or the psychological trauma suffered by women who have abortions. The effect of capital punishment on the crime rate in the United States may also be determinable. This factual information can and should be made available to help people formulate their values about abortion and capital punishment, as well as to enable governments to articulate appropriate policies. Values also frequently come into play in determining what research is appropriate or important to conduct. For instance, the U.S. government has supported and provided funding for research on HIV, AIDS, and cyberterrorism, while denying funding for research using human stem cells.

Stangor, C. (2011). Research methods for the behavioral sciences (4th ed.). Mountain View, CA: Cengage.

Although scientists use research to help establish facts, the distinction between values and facts is not always clear-cut. Sometimes statements that scientists consider to be factual later, on the basis of further research, turn out to be partially or even entirely incorrect. Although scientific procedures do not necessarily guarantee that the answers to questions will be objective and unbiased, science is still the best method for drawing objective conclusions about the world around us. When old facts are discarded, they are replaced with new facts based on newer and more correct data. Although science is not perfect, the requirements of empiricism and objectivity result in a much greater chance of producing an accurate understanding of human behavior than is available through other approaches.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Levels of Explanation in Psychology

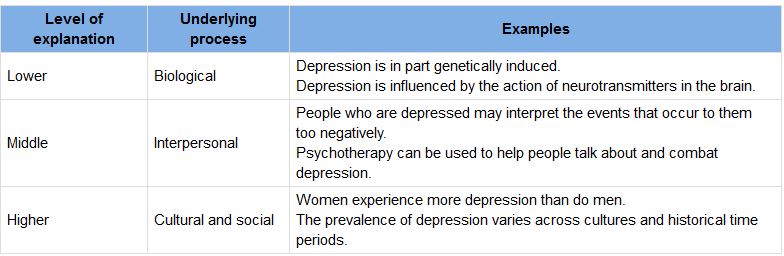

The study of psychology spans many different topics at many different levels of explanation, which are the perspectives that are used to understand behavior. Lower levels of explanation are more closely tied to biological influences, such as genes, neurons, neurotransmitters, and hormones, whereas the middle levels of explanation refer to the abilities and characteristics of individual people, and the highest levels of explanation relate to social groups, organizations, and cultures (Cacioppo, Berntson, Sheridan, & McClintock, 2000).

The same topic can be studied within psychology at different levels of explanation. As one example, you will see that psychological disorders can be understood in terms of the bio-psycho-social model of mental illness which incorporates each of the three levels of explanation.

Stangor, C. (2011). Research methods for the behavioral sciences (4th ed.). Mountain View, CA: Cengage.

The psychological disorder known as depression affects millions of people worldwide and is known to be caused by biological, social, and cultural factors. Studying and helping alleviate depression can be accomplished at low levels of explanation by investigating how chemicals in the brain influence the experience of depression. This approach has allowed psychologists to develop and prescribe drugs, such as Prozac, which may decrease depression in many individuals (Williams, Simpson, Simpson, & Nahas, 2009). At the middle levels of explanation, psychological therapy is directed at helping individuals cope with negative life experiences that may cause depression. At the highest level, psychologists study differences in the prevalence of depression between men and women as well as across cultures. The occurrence of psychological disorders, including depression, is substantially higher for women than for men. It is also higher in Western cultures, such as in the United States, Canada, and Europe, compared to Eastern cultures, such as in India, China, and Japan (Chen, Wang, Poland, & Lin, 2009; Seedat et al., 2009). These sex and cultural differences provide more insight into the factors that cause depression. The study of depression in psychology helps remind us that no one level of explanation can explain everything. All levels of explanation, from biological to personal to cultural, are essential for a complete understanding of human behavior.

Arkes, H. R. (2013). The consequences of the hindsight bias in medical decision making. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22(5), 356-360.

Cacioppo, J. T., Berntson, G. G., Sheridan, J. F., & McClintock, M. K. (2000). Multilevel integrative analyses of human behavior: Social neuroscience and the complementing nature of social and biological approaches. Psychological Bulletin, 126(6), 829–843.

Chen, P.-Y., Wang, S.-C., Poland, R. E., & Lin, K.-M. (2009). Biological variations in depression and anxiety between East and West. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics, 15(3), 283–294; Seedat, S., Scott, K. M., Angermeyer, M. C., Berglund, P., Bromet, E. J., Brugha, T. S.,…Kessler, R. C. (2009). Cross-national associations between gender and mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66(7), 785–795.

Cutler, B. L., & Wells, G. L. (2009). Expert testimony regarding eyewitness identification. In J. L. Skeem, S. O. Lilienfeld, & K. S. Douglas (Eds.), Psychological science in the courtroom: Consensus and controversy (pp. 100–123). New York, NY: Guilford Press; Wells, G. L., & Hasel, L. E. (2008). Eyewitness identification: Issues in common knowledge and generalization. In E. Borgida & S. T. Fiske (Eds.), Beyond common sense: Psychological science in the courtroom (pp. 159–176). Malden, NJ: Blackwell.

Fiske, S. T., & Taylor, S. E. (2007). Social cognition: From brains to culture. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.; Hsee, C. K., & Hastie, R. (2006). Decision and experience: Why don’t we choose what makes us happy? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 10(1), 31–37.

Fleischhut, N., Meder, B., & Gigerenzer, G. (2017). Moral hindsight. Experimental Psychology. Fleischhut, N., Meder, B., & Gigerenzer, G. (2017). Moral hindsight. Experimental Psychology. Fleischhut, N., Meder, B., & Gigerenzer, G. (2017). Moral hindsight. Experimental Psychology. Fleischhut, N., Meder, B., & Gigerenzer, G. (2017). Moral hindsight. Experimental Psychology.

Gilovich, T. (1993). How we know what isn’t so: The fallibility of human reason in everyday life. New York, NY: Free Press.

Nisbett, R. E., & Ross, L. (1980). Human inference: Strategies and shortcomings of social judgment. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Williams, N., Simpson, A. N., Simpson, K., & Nahas, Z. (2009). Relapse rates with long-term antidepressant drug therapy: A meta-analysis. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental, 24(5), 401–408.

Psychology as a Science-Video

CrowderPsychOut. (2014, August 18). Chapter 1-The science of psychology (Part 1) [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XG4xxT0Xjjc. Standard YouTube license.

Summary

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Most psychologists work in research laboratories, hospitals, and other field settings where they study the behavior of humans and animals. Some psychologists are researchers and others are practitioners, but all psychologists use scientific methods to inform their work.

Although it is easy to think that everyday situations have commonsense answers, scientific studies have found that people are not always as good at predicting outcomes as they often think they are. The hindsight bias leads us to think that we could have predicted events that we could not actually have predicted.

Employing the scientific method allows psychologists to objectively and systematically understand human behavior. Psychologists study behavior at different levels of explanation, ranging from lower biological levels to higher social and cultural levels. The same behaviors can be studied and explained within psychology at different levels of explanation.