Social Cognition

Introduction

In this section we will introduce the principles of social cognition—the part of human thinking that helps us understand and predict the behavior of ourselves and others—and consider the ways that our judgments about other people guide our behaviors toward them. We’ll explore how we form impressions of other people, and what makes us like or dislike them.

Social psychologists study our everyday interactions with other people, including the social groups to which we belong. Questions that social psychologists ask include why we are often helpful to other people but at other times are unfriendly or aggressive; why we sometimes conform to the behaviors of others but at other times are able to assert our independence; and what factors help groups work together in effective and productive, rather than in ineffective and unproductive, ways. A fundamental principle of social psychology is that, although we may not always be aware of it, our cognitions, emotions, and behaviors are substantially influenced by the social situation, or the people with whom we are interacting.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Social Psychology

Social Cognition: Making Sense of Ourselves and Others

One important aspect of social cognition involves forming impressions of other people. Making these judgments quickly and accurately helps us guide our behavior to interact appropriately with the people we know. If we can figure out why our roommate is angry at us, we can react to resolve the problem; if we can determine how to motivate the people in our group to work harder on a project, then the project might be better.

Perceiving Others

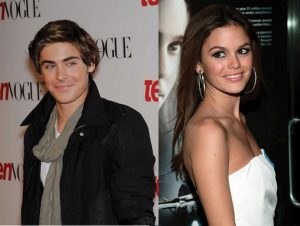

Our initial judgments of others are based in large part on what we see. The physical features of other people, particularly their sex, race, age, and physical attractiveness, are very salient, and we often focus our attention on these dimensions (Schneider, 2003; Zebrowitz & Montepare, 2006). Although it may seem inappropriate or shallow to admit it, we are strongly influenced by the physical attractiveness of others, and in many cases, physical attractiveness is the most important determinant of our initial liking for other people (Walster, Aronson, Abrahams, & Rottmann, 1966). Infants who are only a year old prefer to look at faces that adults consider to be attractive than at unattractive faces (Langlois, Ritter, Roggman, & Vaughn, 1991). Evolutionary psychologists have argued that our belief that “what is beautiful is also good” may be because we use attractiveness as a cue for health; people whom we find more attractive may also, evolutionarily, have been healthier (Zebrowitz, Fellous, Mignault, & Andreoletti, 2003).

One indicator of health is youth. Leslie Zebrowitz and her colleagues (Zebrowitz, 1996; Zebrowitz, Luevano, Bronstad, & Aharon, 2009) have extensively studied the tendency for both men and women to prefer people whose faces have characteristics similar to those of babies. These features include large, round, and widely spaced eyes, a small nose and chin, prominent cheekbones, and a large forehead. People who have baby faces (both men and women) are seen as more attractive than people who are not baby-faced. Another indicator of health is symmetry. People are more attracted to faces that are more symmetrical than they are to those that are less symmetrical, and this may be due in part to the perception that symmetrical faces are perceived as healthier (Rhodes et al., 2001).

Although you might think that we would prefer faces that are unusual or unique, in fact the opposite is true. Langlois and Roggman (1990) showed college students the faces of men and women. The faces were composites made up of the average of 2, 4, 8, 16, or 32 faces. The researchers found that the more faces that were averaged into the stimulus, the more attractive it was judged. Again, our liking for average faces may be because they appear healthier.

Although preferences for youthful, symmetrical, and average faces have been observed cross-culturally, and thus appear to be common human preferences, different cultures may also have unique beliefs about what is attractive. In modern Western cultures, “thin is in,” and people prefer those who have little excess fat (Crandall, Merman, & Hebl, 2009). The need to be thin to be attractive is particularly strong for women in contemporary society, and the desire to maintain a low body weight can lead to low self-esteem, eating disorders, and other unhealthy behaviors. However, the norm of thinness has not always been in place; the preference for women with slender, masculine, and athletic looks has become stronger over the past 50 years. In contrast to the relatively universal preferences for youth, symmetry, and averageness, other cultures do not show such a strong propensity for thinness (Sugiyama, 2005).

Efron photo courtesy of Johan Ferreira. Retrieved from http://www.flickr.com/photos/23664669@N08/2874031622. Licensed under CC BY-2.0. Bilson photo courtesy of Stephen Lovekin / Getty Images. Retrieved from http://www.flickr.com/photos/34128229@N06/3182841715. Licensed under CC BY-2.0. Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Crandall, C. S., Merman, A., & Hebl, M. (2009). Anti-fat prejudice. In T. D. Nelson (Ed.), Handbook of prejudice, stereotyping, and discrimination (pp. 469–487). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Langlois, J. H., Ritter, J. M., Roggman, L. A., & Vaughn, L. S. (1991). Facial diversity and infant preferences for attractive faces. Developmental Psychology, 27(1), 79–84.

Langlois, J. H., & Roggman, L. A. (1990). Attractive faces are only average. Psychological Science, 1(2), 115–121.

Rhodes, G., Zebrowitz, L. A., Clark, A., Kalick, S. M., Hightower, A., & McKay, R. (2001). Do facial averageness and symmetry signal health? Evolution and Human Behavior, 22(1), 31–46.

Schneider, D. J. (2004). The psychology of stereotyping. New York, NY: Guilford Press; Zebrowitz, L. A., & Montepare, J. (2006). The ecological approach to person perception: Evolutionary roots and contemporary offshoots. In M. Schaller, J. A. Simpson, & D. T. Kenrick (Eds.), Evolution and social psychology (pp. 81–113). Madison, CT: Psychosocial Press.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Sugiyama, L. S. (2005). Physical attractiveness in adaptationist perspective. In D. M. Buss (Ed.), The handbook of evolutionary psychology (pp. 292–343). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons

Walster, E., Aronson, V., Abrahams, D., & Rottmann, L. (1966). Importance of physical attractiveness in dating behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 4(5), 508–516.

Zebrowitz, L. A., Fellous, J.-M., Mignault, A., & Andreoletti, C. (2003). Trait impressions as overgeneralized responses to adaptively significant facial qualities: Evidence from connectionist modeling. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 7(3), 194–215.

Zebrowitz, L. A. (1996). Physical appearance as a basis of stereotyping. In C. N. Macrae, C. Stangor, & M. Hewstone (Eds.), Stereotypes and stereotyping (pp. 79–120). New York, NY: Guilford Press; Zebrowitz, L. A., Luevano, V. X., Bronstad, P. M., & Aharon, I. (2009). Neural activation to babyfaced men matches activation to babies. Social Neuroscience, 4(1), 1–10.

Forming Judgements on the Basis of Appearance: Stereotyping, Prejudice and Discrimination

We frequently use people’s appearances to form our judgments about them and to determine our responses to them. The tendency to attribute personality characteristics to people on the basis of their external appearance or their social group memberships is known as stereotyping. Our stereotypes about physically attractive people lead us to see them as more dominant, sexually warm, mentally healthy, intelligent, and socially skilled than we perceive physically unattractive people (Langlois et al., 2000). Our stereotypes lead us to treat people differently—the physically attractive are given better grades on essay exams, are more successful on job interviews, and receive lighter sentences in court judgments than their less attractive counterparts (Hosoda, Stone-Romero, & Coats, 2003; Zebrowitz & McDonald, 1991). African American high school students in the U.S. are more than twice as likely to be suspended from school at some time as are White students (Okonofua, Walton, & Eberhardt, 2016).

In addition to stereotypes about physical attractiveness, we also regularly stereotype people on the basis of their sex, race, age, religion, and many other characteristics, and these stereotypes can frequently be negative (Schneider, 2004). Stereotyping is unfair to the people we judge because stereotypes are based on our preconceptions and negative emotions about the members of the group. Stereotyping is closely related to prejudice, the tendency to dislike people because of their appearance or group memberships, and discrimination, negative behaviors toward others based on prejudice. Stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination work together. We may not vote for a gay person for public office because of our negative stereotypes about gays, and we may avoid people from other religions or those with mental illness because of our prejudices.

Some stereotypes may be accurate in part. Research has found, for instance, that attractive people are actually more sociable, more popular, and less lonely than less attractive individuals (Langlois et al., 2000). Consistent with the stereotype that women are “emotional,” women are, on average, more empathic and attuned to the emotions of others than are men (Hall & Schmid Mast, 2008). Group differences in personality traits may occur because people act toward others on the basis of their stereotypes, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy. A self-fulfilling prophecy occurs when our expectations about the personality characteristics of others lead us to behave toward those others in ways that make those beliefs come true. If I have a stereotype that attractive people are friendly, then I may act in a friendly way toward people who are attractive. This friendly behavior may be reciprocated by the attractive person, and if many other people also engage in the same positive behaviors with the person, in the long run he or she may actually become friendlier. But even if attractive people are, on average, friendlier than unattractive people, not all attractive people are friendlier than all unattractive people. And even if women are, on average, more emotional than men, not all men are less emotional than all women.

We use our stereotypes and prejudices because they are easy; if we can quickly size up people on the basis of their physical appearance it can save us a lot of time and effort. We may be evolutionarily disposed to stereotyping, because our primitive ancestors needed to accurately separate members of their own kin group from those of others, categorizing people into “us” (the

ingroup) and “them” (the outgroup) was useful and even necessary (Neuberg, Kenrick, & Schaller, 2010). The positive emotions that we experience as a result of our group memberships—known as social identity—can be an important and positive part of our everyday experiences (Hogg, 2003). We may gain social identity as members of our university, our sports teams, our religious and racial groups, and many other groups.

But the fact that we may use our stereotypes does not mean that we should use them. Stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination, whether they are consciously or unconsciously applied, make it difficult for some people to effectively contribute to society and may create both mental and physical health problems for them (Swim & Stangor, 1998). In some cases, getting beyond our prejudices is required by law, as detailed in the US Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Fair Housing Act of 1968, and the Equal Opportunity Employment Act of 1972.

There are individual differences in prejudice, such that some people are more likely to try to control and confront their stereotypes and prejudices whereas others apply them more freely (Czopp, Monteith, & Mark, 2006; Plant & Devine, 1998). For instance, some people believe in group hierarchies—that some groups are naturally better than others—whereas other people are more egalitarian and hold fewer prejudices (Ho et al., 2015). Our stereotypes and prejudices also have close relationships to our political beliefs, and our voting behavior is determined, in part by our attitudes toward people from different social groups (Lundberg & Payne, 2014).

Social psychologists believe that we should work to get past our prejudices. The tendency to hold stereotypes and prejudices and to act on them can be reduced, for instance, through positive interactions and friendships with members of other groups, by talking to people about their prejudices, through practice in avoiding using them, and through education (Broockman and Kalla, 2016; Hewstone, 1996).

Broockman D., Kalla J. (2016). Durably reducing transphobia: A field experiment on door-to-door canvassing. Science, 352, 220–224. Broockman D., Kalla J. (2016). Hewstone, M. (1996). Contact and categorization: Social psychological interventions to change intergroup relations. In C. N. Macrae, C. Stangor, & M. Hewstone (Eds.), Stereotypes and stereotyping (pp. 323–368). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Czopp, A. M., Monteith, M. J., & Mark, A. Y. (2006). Standing up for a change: Reducing bias through interpersonal confrontation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(5), 784–803; Plant, E. A., & Devine, P. G. (1998). Internal and external motivation to respond without prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(3), 811–832.

Fiske, S. T. (1989). Examining the role of intent: Toward understanding its role in stereotyping and prejudice. In J. S. Uleman & J. A. Bargh (Eds.), Unintended thought (pp. 253–286). New York, NY: Guilford Press; Stangor, C. (1995). Content and application inaccuracy in social stereotyping. In Y. T. Lee, L. J. Jussim, & C. R. McCauley (Eds.), Stereotype accuracy: Toward appreciating group differences (pp. 275–292). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Hall, J. A., & Schmid Mast, M. (2008). Are women always more interpersonally sensitive than men? Impact of goals and content domain. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(1), 144–155.

Ho, A. K., Sidanius, J., Kteily, N., Sheehy-Skeffington, J., Pratto, F., Henkel, K. E., & … Stewart, A. L. (2015). The nature of social dominance orientation: Theorizing and measuring preferences for intergroup inequality using the new SDO₇ scale. Journal Of Personality And Social Psychology, 109(6), 1003-1028. doi:10.1037/pspi0000033.

Hogg, M. A. (2003). Social identity. In M. R. Leary & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), Handbook of self and identity (pp. 462–479). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Hosoda, M., Stone-Romero, E. F., & Coats, G. (2003). The effects of physical attractiveness on job-related outcomes: A meta-analysis of experimental studies. Personnel Psychology, 56(2), 431–462; Zebrowitz, L. A., & McDonald, S. M. (1991). The impact of litigants’ baby-facedness and attractiveness on adjudications in small claims courts. Law & Human Behavior, 15(6), 603–623.

Langlois, J. H., Kalakanis, L., Rubenstein, A. J., Larson, A., Hallam, M., & Smoot, M. (2000). Maxims or myths of beauty? A meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychological Bulletin, 126(3), 390–423.

Lundberg KB, Payne BK (2014) Decisions among the Undecided: Implicit Attitudes Predict Future Voting Behavior of Undecided Voters. PLOS ONE 9(1): e85680.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0085680.

Neuberg, S. L., Kenrick, D. T., & Schaller, M. (2010). Evolutionary social psychology. In S. T. Fiske, D. T. Gilbert, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (5th ed., Vol. 2, pp. 761–796). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Okonofua, J. A., Walton, G. M., & Eberhardt, J. L. (2016). A Vicious Cycle. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11(3), 381–398. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691616635592.

Schneider, D. J. (2004). The psychology of stereotyping. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Swim, J. T., & Stangor, C. (1998). Prejudice: The target’s perspective. Santa Barbara, CA: Academic Press.

Forming Judgements by Observing Others

When we observe people’s behavior we may attempt to determine if the behavior really reflects their underlying personality. If Frank hits Joe, we might wonder if Frank is naturally aggressive or if perhaps Joe had provoked him. If Leslie leaves a big tip for the waitress, we might wonder if she is a generous person or if the service was particularly excellent. The process of trying to determine the causes of people’s behavior, with the goal of learning about their personalities, is known as causal attribution (Jones et al., 1987). Making causal attributions is a bit like conducting an experiment. We carefully observe the people we are interested in and note how they behave in different social situations. After we have made our observations, we draw our conclusions. Sometimes we may decide that the behavior was caused primarily by the person; this is called making a person attribution. At other times, we may determine that the behavior was caused primarily by the situation; this is called making a situation attribution. And at other times we may decide that the behavior was caused by both the person and the situation.

Although people are reasonably accurate in their attributions (we could say, perhaps, that they are “good enough”; Fiske, 2003), they are far from perfect. One error that we frequently make when making judgments about ourselves is to make self-serving attributions by judging the causes of our own behaviors in overly positive ways. If you did well on a test, you will probably attribute that success to personal causes (“I’m smart,” “I studied really hard”), but if you do poorly on the test you are more likely to make situational attributions (“The test was hard,” “I had bad luck”). Although making causal attributions is expected to be logical and scientific, our emotions are not irrelevant.

Another way that our attributions are often inaccurate is that we are, by and large, too quick to attribute the behavior of other people to something personal about them rather than to something about their situation. We are more likely to say, “Leslie left a big tip, so she must be generous” than “Leslie left a big tip, but perhaps that was because the service was really excellent.” The common tendency to overestimate the role of person factors and overlook the impact of situations in judging others is known as the fundamental attribution error (or correspondence bias).

The fundamental attribution error occurs in part because other people are so salient in our social environments. When I look at you, I see you as my focus, and so I am likely to make personal attributions about you. If the situation is reversed, such that people see situations from the perspectives of others, the fundamental attribution error is reduced (Storms, 1973). And when we judge people, we often see them in only one situation. It’s easy for you to think that your math professor is “picky and detail-oriented” because that describes her behavior in class, but you don’t know how she acts with her friends and family, which might be completely different. And we also tend to make person attributions because they are easy. We are more likely to commit the fundamental attribution error—quickly jumping to the conclusion that behavior is caused by underlying personality—when we are tired, distracted, or busy doing other things (Trope & Alfieri, 1997).

An important moral about perceiving others applies here: We should not be too quick to judge other people. It is easy to think that poor people are lazy, that people who say something harsh are rude or unfriendly, and that all terrorists are insane madmen. But these attributions may frequently overemphasize the role of the person, resulting in an inappropriate and inaccurate tendency to blame the victim (Lerner, 1980; Tennen & Affleck, 1990). Sometimes people are lazy and rude, and some terrorists are probably insane, but these people may also be influenced by the situation in which they find themselves. Poor people may find it more difficult to get work and education because of the environment they grow up in; people may say rude things because they are feeling threatened or are in pain; and terrorists may have learned in their family and school that committing violence in the service of their beliefs is justified.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Attitudes and Behavior

Attitude refers to our relatively enduring evaluations of people and things (Albarracín, Johnson, & Zanna, 2005). We each hold many thousands of attitudes, including those about family and friends, political parties and political figures, abortion rights, preferences for music, and much more. Some of our attitudes, including those about sports, roller coaster rides, and capital punishment, are heritable, which explains in part why we are similar to our parents on many dimensions (Olson, Vernon, Harris, & Jang, 2001). Other attitudes are learned through direct and indirect experiences with the attitude objects (De Houwer, Thomas, & Baeyens, 2001). Attitudes are important because they frequently (but not always) predict behavior. If we know that a person has a more positive attitude toward Frosted Flakes than toward Cheerios, then we will naturally predict that she will buy more of the former when she gets to the market. If we know that Charlie is madly in love with Charlene, then we will not be surprised when he proposes marriage. Because attitudes often predict behavior, people who wish to change behavior frequently try to change attitudes through the use of persuasive communications.

Attitudes predict behavior better for some people than for others. People who are high in

self-monitoring—the tendency to regulate behavior to meet the demands of social situations—tend to change their behaviors to match the social situation and thus do not always act on their attitudes (Gangestad & Snyder, 2000). High self-monitors agree with statements such as, “In different situations and with different people, I often act like very different persons” and “I guess I put on a show to impress or entertain people.” Attitudes are more likely to predict behavior for low self-monitors, who are more likely to act on their own attitudes even when the social situation suggests that they should behave otherwise. Low self-monitors are more likely to agree with statements such as “At parties and social gatherings, I do not attempt to do or say things that others will like” and “I can only argue for ideas that I already believe.”

The match between the social situations in which the attitudes are expressed and the behaviors are engaged in also matters, such that there is a greater attitude-behavior correlation when the social situations match. Imagine for a minute the case of Magritte, a 16-year-old high school student. Magritte tells her parents that she hates the idea of smoking cigarettes. But how sure are you that Magritte’s attitude will predict her behavior? Would you be willing to bet that she’d never try smoking when she’s out with her friends? The problem here is that Magritte’s attitude is being expressed in one social situation (when she is with her parents) whereas the behavior (trying a cigarette) is going to occur in a very different social situation (when she is out with her friends). The relevant social norms are, of course, much different in the two situations. Magritte’s friends might be able to convince her to try smoking, despite her initial negative attitude, by enticing her with peer pressure. Behaviors are more likely to be consistent with attitudes when the social situation in which the behavior occurs is similar to the situation in which the attitude is expressed (Ajzen, 1991).

Although it might not have surprised you to hear that our attitudes predict our behaviors, you might be more surprised to learn that our behaviors also have an influence on our attitudes. It makes sense that if I like Frosted Flakes I’ll buy them, because my positive attitude toward the product influences my behavior. But my attitudes toward Frosted Flakes may also become more positive if I decide—for whatever reason—to buy some. It makes sense that Charlie’s love for Charlene will lead him to propose marriage, but it is also the case that he will likely love Charlene even more after he does so. Behaviors influence attitudes in part through the process of self-perception. Self-perception occurs when we use our own behavior as a guide to help us determine our own thoughts and feelings (Bem, 1972; Olson & Stone, 2005). In one demonstration of the power of self-perception, Wells and Petty (1980) assigned their research participants to shake their heads either up and down or side to side as they read newspaper editorials. The participants who had shaken their heads up and down later agreed with the content of the editorials more than the people who had shaken them side to side. Wells and Petty argued that this occurred because the participants used their own head-shaking behaviors to determine their attitudes about the editorials.

Persuaders may use the principles of self-perception to change attitudes. The foot-in-the-door technique is a method of persuasion in which the person is first persuaded to accept a rather minor request and then asked for a larger one after that. In one demonstration, Guéguen and Jacob (2002) found that students in a computer discussion group were more likely to volunteer to complete a 40-question survey on their food habits (which required 15 to 20 minutes of their time) if they had already, a few minutes earlier, agreed to help the same requestor with a simple computer-related question (about how to convert a file type) than if they had not first been given the smaller opportunity to help. The idea is that when asked the second time, the people looked at their past behavior (having agreed to the small request) and inferred that they are helpful people.

Behavior also influences our attitudes through a more emotional process known as cognitive dissonance. Cognitive dissonance refers to the discomfort we experience when we choose to behave in ways that we see as inappropriate (Festinger, 1957; Harmon-Jones & Mills, 1999). If we feel that we have wasted our time or acted against our own moral principles, we experience negative emotions (dissonance) and may change our attitudes about the behavior to reduce the negative feelings. Elliot Aronson and Judson Mills (1959) studied whether the cognitive dissonance created by an initiation process could explain how much commitment students felt to a group that they were part of. In their experiment, female college students volunteered to join a group that would be meeting regularly to discuss various aspects of the psychology of sex. According to random assignment, some of the women were told that they would be required to perform an embarrassing procedure (they were asked to read some obscene words and some sexually oriented passages from a novel in public) before they could join the group, whereas other women did not have to go through this initiation. Then all the women got a chance to listen to the group’s conversation, which turned out to be very boring.

Aronson and Mills found that the women who had gone through the embarrassing experience subsequently reported more liking for the group than those who had not. They argued that the more effort an individual expends to become a member of the group (e.g., a severe initiation), the more they will become committed to the group, to justify the effort they have put in during the initiation. The idea is that the effort creates dissonant cognitions (“I did all this work to join the group”), which are then justified by creating more consonant ones (“OK, this group is really pretty fun”). Thus the women who spent little effort to get into the group were able to see the group as the dull and boring conversation that it was. The women who went through the more severe initiation, however, succeeded in convincing themselves that the same discussion was a worthwhile experience.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior & Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211.

Albarracín, D., Johnson, B. T., & Zanna, M. P. (Eds.). (2005). The handbook of attitudes. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Aronson, E., & Mills, J. (1959). The effect of severity of initiation on liking for a group. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 59, 171–181.

Bem, D. J. (1972). Self-perception theory. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 6). New York, NY: Academic Press; Olson, J. M., & Stone, J. (2005). The influence of behavior on attitudes. In D. Albarracín, B. T. Johnson, & M. P. Zanna (Eds.), The handbook of attitudes (pp. 223–271). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Cialdini, R. B. (2001). Influence: Science and practice (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

De Houwer, J., Thomas, S., & Baeyens, F. (2001). Association learning of likes and dislikes: A review of 25 years of research on human evaluative conditioning. Psychological Bulletin, 127(6), 853–869.

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Evanston, IL: Row, Peterson; Harmon-Jones, E., & Mills, J. (1999). Cognitive dissonance: Progress on a pivotal theory in social psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Fiske, S. T. (2003). Social beings. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Gangestad, S. W., & Snyder, M. (2000). Self-monitoring: Appraisal and reappraisal. Psychological Bulletin, 126(4), 530–555.

Guéguen, N., & Jacob, C. (2002). Solicitation by e-mail and solicitor’s status: A field study of social influence on the web. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 5(4), 377–383.

Jones, E. E., Davis, K. E., & Gergen, K. J. (1961). Role playing variations and their informational value for person perception. Journal of Abnormal & Social Psychology, 63(2), 302–310.

Lerner, M. (1980). The belief in a just world: A fundamental delusion. New York, NY: Plenum; Tennen, H., & Affleck, G. (1990). Blaming others for threatening events. Psychological Bulletin, 108(2), 209–232.

Olson, J. M., Vernon, P. A., Harris, J. A., & Jang, K. L. (2001). The heritability of attitudes: A study of twins. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 80(6), 845–860.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Storms, M. D. (1973). Videotape and the attribution process: Reversing actors’ and observers’ points of view. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 27(2), 165–175.

Trope, Y., & Alfieri, T. (1997). Effortfulness and flexibility of dispositional judgment processes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73(4), 662–674.

Wells, G. L., & Petty, R. E. (1980). The effects of overt head movements on persuasion: Compatibility and incompatibility of responses. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 1(3), 219–230.

Social Psychology

CrashCourse. (2014, November 3). Social thinking: Crash course #37. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h6HLDVOTQ8. Standard YouTube license.

Lisa Fosbender. (2013, June 22). Psychology 101: Physical attraction. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0F_vW7I-Tnc. Standard YouTube License.

Summary

In this section we explored social cognition and how to better understand the world around us. Our initial judgments of others are based, in large part, on what we see. The physical features of other people—particularly their sex, race, age, and physical attractiveness—are very salient, and we often focus our attention on these dimensions. At least in some cases, people can draw accurate conclusions about others on the basis of physical appearance. Youth, symmetry, and averageness have been found to be cross-culturally consistent determinants of perceived attractiveness, although different cultures may also have unique beliefs about what is attractive.

Causal attribution is the process of trying to determine the causes of people’s behavior. Attributions may be made to the person, to the situation, or to a combination of both. Although people are reasonably accurate in their attributions, they may make self-serving attributions and fall victim to the fundamental attribution error. Attitudes refer to our relatively enduring evaluations of people and things. Attitudes are important because they frequently (but not always) predict behavior. Attitudes can be changed through persuasive communications. Attitudes predict behavior better for some people than for others, and in some situations more than others. Our behaviors also influence our attitudes through the cognitive processes of self-perception and the more emotional process of cognitive dissonance.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.