Somatic, Sexual, and Eating Disorders

Introduction

Although mood, anxiety, and personality disorders represent the most prevalent diagnoses, there are a variety of other disorders that affect people. The complexity of symptoms and classifications helps make it clear how difficult it is to accurately and consistently diagnose and treat psychological disorders. In this section, we will review several other disorders that are of interest to psychologists and that affect millions of people. These disorders include disorders related to somatic symptoms, sexual disorders and eating disorders.

We have seen that the biological aspect of the bio-psycho-social model of psychological disorders focuses on how closely our mental health is related to our biology. In some cases, psychological disorders are directly related to the experience or expression of physical symptoms. In somatic symptom disorder the physical symptoms are real, whereas in factitious disorders they are not.

Sexual disorders refer to a variety of problems revolving around performing or enjoying sex. These include disorders related to sexual function, gender identity, and sexual preference. Sexual dysfunctions refer to a set of psychological disorders that occur when the physical sexual response cycle is inadequate for reproduction or for sexual enjoyment.

In this section we will also explore healthy and unhealthy eating patterns, some of which include anorexia nervosa and bulimia. Anorexia nervosa is an eating disorder characterized by extremely low body weight, distorted body image, and an obsessive fear of gaining weight. Nine out of 10 sufferers are women. Anorexia begins with a severe weight loss diet and develops into a preoccupation with food and dieting. Bulimia nervosa is an eating disorder characterized by binge eating followed by purging.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Somatic Symptom and Related Disorders, Sexual Disorders, and Eating Disorders

Somatic Symptom and Related Disorders

Somatization symptom disorder (SSD) is a psychological disorder in which a person experiences numerous long-lasting but seemingly unrelated physical ailments that have no identifiable physical cause. The diagnosis is only made if the person has experienced the symptoms for at least six months. A person with SSD might complain of joint aches, vomiting, nausea, muscle weakness, and sexual dysfunction. The symptoms that result from SSD are real and cause distress to the individual, but they are due entirely to psychological factors. SSD is more likely to occur when the person is under stress, and it may disappear naturally over time. SSD is more common in women than in men, and usually first appears in adolescents or those in their early 20s.

One type of SSD is conversion disorder, a psychological disorder in which patients experience specific neurological symptoms such as numbness, blindness, or paralysis, but where no neurological explanation is observed or possible (Agaki & House, 2001). The difference between conversion and other SSDs is in terms of the location of the physical complaint. In SSD, the malaise is general, whereas in conversion disorder there are one or several specific neurological symptoms. The patient often misinterprets normal body symptoms such as coughing, perspiring, headaches, or a rapid heartbeat as signs of serious illness, and the patient’s concerns remain even after he or she has been medically evaluated and assured that the health concerns are unfounded.

Conversion disorder gets its name from the idea that the existing psychological disorder is “converted” into the physical symptoms. It was the observation of conversion disorder (then known as “hysteria”) that first led Sigmund Freud to become interested in the psychological aspects of illness in his work with Jean-Martin Charcot. Conversion disorder is not common (a prevalence of less than 1%), but it may, in many cases, be undiagnosed.

Two other psychological disorders relate to the experience of physical problems that are not real. Patients with factitious disorder fake physical symptoms, in large part, because they enjoy the attention and treatment that they receive in the hospital. They may lie about symptoms, alter diagnostic tests such as urine samples to mimic disease, or even injure themselves to bring on more symptoms. In the more severe form of factitious disorder known as Münchausen syndrome, the patient has a lifelong pattern of a series of successive hospitalizations for faked symptoms.

Factitious disorder is distinguished from another related disorder known as malingering, which also involves fabricating the symptoms of mental or physical disorders, but where the motivation for doing so is to gain financial reward; to avoid school, work, or military service; to obtain drugs; or to avoid prosecution.

Somatoform and factitious disorders are problematic not only for the patient, but they also have societal costs. People with these disorders frequently follow through with potentially dangerous medical tests and are at risk for drug addiction from the drugs they are given and for injury from the complications of the operations they submit to (Bass, Peveler, & House, 2001; Looper & Kirmayer, 2002). Additionally, people with these disorders may take up hospital space that is needed for people who are really ill. To help combat these costs, emergency room and hospital workers use a variety of tests for detecting these disorders.

Akagi, H., & House, A. O. (2001). The epidemiology of hysterical conversion. In P. Halligan, C. Bass, & J. Marshall (Eds.), Hysterical conversion: Clinical and theoretical perspectives (pp. 73–87). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Bass, C., Peveler, R., & House, A. (2001). Somatoform disorders: Severe psychiatric illnesses neglected by psychiatrists. British Journal of Psychiatry, 179, 11–14; Looper, K. J., & Kirmayer, L. J. (2002). Behavioral medicine approaches to somatoform disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70(3), 810–827.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Sexual Dysfunctions

Sexual disorders refer to a variety of problems revolving around performing or enjoying sex. These include disorders related to sexual function, gender identity, and sexual preference.

Sexual Dysfunction

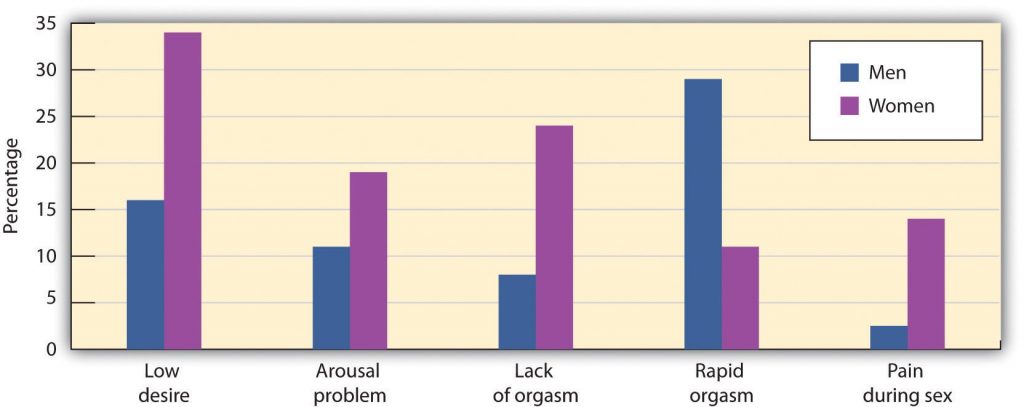

Sexual dysfunctions refer to a set of psychological disorders that occur when the physical sexual response cycle is inadequate for reproduction or for sexual enjoyment. There are a variety of potential problems, and their nature varies for men and women. Sexual disorders affect up to 43% of women and 31% of men (Laumann, Paik, & Rosen, 1999). Sexual disorders are often difficult to diagnose because in many cases the dysfunction occurs at the partner level (one or both of the partners are disappointed with the sexual experience) rather than at the individual level.

| Disorder | Description |

| Male hypoactive sexual desire disorder | Persistently or recurrently deficient (or absent) sexual fantasies and desire for sexual activity |

| Female sexual interest/arousal disorder | Persistent or recurrent inability to attain, or to maintain until completion of the sexual activity, an adequate lubrication-swelling response of sexual excitement |

| Male erectile disorder | Persistent or recurrent inability to attain or maintain an adequate erection until completion of the sexual activity |

| Premature ejaculation | Persistent or recurrent ejaculation with minimal sexual stimulation before, on, or shortly after penetration and before the person wishes it |

| Female genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorders | Disorders that make it painful to have sex. |

Female sexual interest/arousal disorder refers to persistent difficulties becoming sexually aroused or sufficiently lubricated in response to sexual stimulation in women. The disorder may be comorbid with hypoactive sexual desire, orgasmic disorder, mood disorders or anxiety disorders.

Male erectile disorder (sometimes referred to as “impotence”) refers to persistent and dysfunctional difficulty in achieving or maintaining an erection sufficient to complete sexual activity. Prevalence rates vary by age, from about 6% of college-aged males to 35% of men in their 70s. About half the men aged 40 to 70 report having problems getting or maintaining an erection “now and then.”

Most erectile dysfunction occurs as a result of physiological factors, including illness, and the use of medications, alcohol, or other recreational drugs. Erectile dysfunction is also related to anxiety, low self-esteem, and general problems in the particular relationship.

One of the most common sexual dysfunctions in men is premature ejaculation. It is not possible to exactly specify what defines “premature,” but if the man ejaculates before or immediately upon insertion of the penis into the vagina, most clinicians will identify the response as premature. Most men diagnosed with premature ejaculation ejaculate within one minute after insertion (Waldinger, 2003). Premature ejaculation is one of the most prevalent sexual disorders and causes much anxiety in many men.

Female orgasmic disorder refers to the inability to obtain orgasm in women. The woman enjoys sex and foreplay and shows normal signs of sexual arousal but cannot reach the peak experience of orgasm. Male orgasmic disorder includes a delayed or retarded ejaculation (very rare) or (more commonly) premature ejaculation.

Finally, female genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder refers to disorders that create pain and involuntary spasms in women and thus make it painful to have sex. In most cases, these problems are biological and can be treated with hormones, creams, or surgery.

Sexual dysfunctions have a variety of causes. In some cases the primary problem is biological, and the disorder may be treated with medication. Other causes include a repressive upbringing in which the parents have taught the person that sex is dirty or sinful, or the experience of sexual abuse (Beitchman, Zucker, Hood, & DaCosta, 1992). In some cases, the sex problem may be due to the fact that the person has a different sexual orientation than he or she is engaging in. Other problems include poor communication between the partners, a lack of sexual skills, and (particularly for men) performance anxiety.

Source: Adapted from Laumann, E. O., Paik, A., & Rosen, R. C. (1999). Sexual dysfunction in the United States: Prevalence and predictors. Journal of the American Medical Association, 281(6), 537–544.Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Gender Identity Disorder

Gender identity refers to the identification with a sex. Most children develop an appropriate attachment to their own sex. In some cases, however; children or adolescents—sometimes even those as young as 3 or 4 years old—believe that they have been trapped in a body of the wrong sex. Gender identity disorder (GID, or transsexualism) is diagnosed when the individual displays a repeated and strong desire to be the other sex, a persistent discomfort with one’s sex, and a belief that one was born as the wrong sex, accompanied by significant dysfunction and distress. GID usually appears in adolescence or adulthood and may intensify over time (Bower, 2001). Since many cultures strongly disapprove of cross-gender behavior, it often results in significant problems for affected persons and those in close relationships with them.

Gender identity disorder is rare, occurring only in about 1 in every 12,000 males and 1 in every 30,000 females (Olsson & Möller, 2003). The causes of GID are yet unknown, although they seem to be related to the amount of testosterone and other hormones in the uterus (Kraemer, Noll, Delsignore, Milos, Schnyder, & Hepp, 2009).

The classification of GID as a mental disorder has been challenged because people who suffer from GID do not regard their own cross-gender feelings and behaviors as a disorder and do not feel that they are distressed or dysfunctional. People suffering from GID often argue that a “normal” gender identity may not necessarily involve identification with one’s own biological sex. GID represents another example, then, of how culture defines disorder.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Paraphilias

Another class of sexual disorders relates to sexual practices and interest. In some cases, sexual interest is so unusual that it is known as a paraphilia—a sexual deviation where sexual arousal is obtained from a consistent pattern of inappropriate responses to objects or people, and in which the behaviors associated with the feelings are distressing and dysfunctional. Paraphilias may sometimes be only fantasies, and in other cases may result in actual sexual behavior.

- Bestiality=Sex with animals

- Exhibitionism=Exposing genitals to an unsuspecting person

- Fetishism=Nonliving or unusual objects or clothing of the opposite sex

- Frotteurism=Rubbing up against unsuspecting persons

- Masochism=Being beaten, humiliated, bound, or otherwise made to suffer

- Pedophilia=Sexual activity with a prepubescent child

- Sadism=Witnessing suffering of another person

- Voyeurism=Observing an unsuspecting person who is naked, disrobing, or engaged in intimate behavior

People with paraphilias are usually rejected by society but for two different reasons. In some cases, such as voyeurism and pedophilia, the behavior is unacceptable (and illegal) because it involves a lack of consent on the part of the recipient of the sexual advance. But other paraphilias are rejected simply because they are unusual, even though they are consensual and do not cause distress or dysfunction to the partners. Sexual sadism and sexual masochism, for instance, are usually practiced consensually, and thus may not be harmful to the partners or to society. A recent survey found that individuals who engage in sadism and masochism are as psychologically healthy as those who do not (Connolly, 2006).

Beitchman, J. H., Zucker, K. J., Hood, J. E., & DaCosta, G. A. (1992). A review of the long-term effects of child sexual abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect, 16(1), 101–118.

Bower, H. (2001). The gender identity disorder in the DSM-IV classification: A critical evaluation. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 35(1), 1–8.

Connolly, P. (2006). Psychological functioning of bondage/domination/sado-masochism (BDSM) practitioners. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality, 18(1), 79–120. doi:10.1300/j056v18n01_05.

Donahey, K. M., & Carroll, R. A. (1993). Gender differences in factors associated with hypoactive sexual desire. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 19(1), 25–40.

Kraemer, B., Noll, T., Delsignore, A., Milos, G., Schnyder, U., & Hepp, U. (2009). Finger length ratio (2D:4D) in adults with gender identity disorder. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38(3), 359–363.

Laumann, E. O., Paik, A., Rosen, R. (1999). Sexual dysfunction in the United States. Journal of the American Medical Association, 281(6), 537–544.

Olsson, S.-E., & Möller, A. R. (2003). On the incidence and sex ratio of transsexualism in Sweden, 1972–2002. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 32(4), 381–386.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Waldinger, M. D. (2003). Rapid ejaculation. In S. B. Levine, C. B. Risen, & S. E. Althof (Eds.), Handbook of clinical sexuality for mental health professionals (pp. 257–274). New York, NY: Brunner-Routledge.

Eating and Feeding Disorders

Like most psychological phenomena, the simple behavior of eating has both biological and social determinants. Biologically, hunger is controlled by the interactions among complex pathways in the nervous system and a variety of hormonal and chemical systems in the brain and body. The stomach is of course important. We feel more hungry when our stomach is empty than when it is full. But we can also feel hunger even without input from the stomach. Two areas of the hypothalamus are known to be particularly important in eating. The lateral part of the hypothalamus responds primarily to cues to start eating, whereas the ventromedial part of the hypothalamus primarily responds to cues to stop eating. If the lateral part of the hypothalamus is damaged, the animal will not eat even if food is present, whereas if the ventromedial part of the hypothalamus is damaged, the animal will eat until it is obese (Wolf & Miller, 1964)

Normally the interaction of the various systems that determine hunger creates a balance or homeostasis in which we eat when we are hungry and stop eating when we feel full. But homeostasis varies among people; some people simply weigh more than others, and there is little they can do to change their fundamental weight. Weight is determined in large part by the basal metabolic rate, the amount of energy expended while at rest. Each person’s basal metabolic rate is different, due to his or her unique physical makeup and physical behavior. A naturally occurring low metabolic rate, which is determined entirely by genetics, makes weight management a very difficult undertaking for many people.

How we eat is also influenced by our environment. When researchers rigged clocks to move faster, people got hungrier and ate more, as if they thought they must be hungry again because so much time had passed since they last ate (Schachter, 1968). And if we forget that we have already eaten, we are likely to eat again even if we are not actually hungry (Rozin, Dow, Moscovitch, & Rajaram, 1998).

Cultural norms about appropriate weights also influence eating behaviors. Current norms for women in Western societies are based on a very thin body ideal, emphasized by television and movie actresses, models, and even children’s dolls, such as the ever-popular Barbie. These norms for excessive thinness are very difficult for most women to attain: Barbie’s measurements, if translated to human proportions, would be about 36 in.-18 in.-33 in. at bust-waist-hips, measurements that are attained by less than 1 in 100,000 women (Norton, Olds, Olive, & Dank, 1996). Many women idealize being thin and yet are unable to reach the standard that they prefer. In some cases, the desire to be thin can lead to eating disorders, which are estimated to affect about 1 million males and 10 million females in the United States alone (Hoek & van Hoeken, 2003; Patrick, 2002).

Eating disorders are, in part, heritable (Klump, Burt, McGue, & Iacono, 2007), and it is not impossible that at least some have been selected through their evolutionary significance in coping with food shortages (Guisinger, 2008). Eating disorders are also related to psychological causes, including low self-esteem, perfectionism, and the perception that one’s body weight is too high (Vohs et al., 2001). Cultural norms about body weight and eating may also contribute to the development of an eating disorder (Crandall, 1988). Because eating disorders can create profound negative health outcomes, including death, people who suffer from them should seek treatment. This treatment is often quite effective.

Anorexia nervosa is an eating disorder characterized by extremely low body weight, distorted body image, and an obsessive fear of gaining weight. Nine out of 10 sufferers are women. Anorexia begins with a severe weight loss diet and develops into a preoccupation with food and dieting.

Bulimia nervosa is an eating disorder characterized by binge eating followed by purging. Bulimia nervosa begins after the dieter has broken a diet and gorged. Bulimia involves repeated episodes of overeating, followed by vomiting, laxative use, fasting, or excessive exercise. It is most common in women in their late teens or early 20s, and it is often accompanied by depression and anxiety, particularly around the time of the binging. The cycle in which the person eats to feel better, but then after eating becomes concerned about weight gain and purges, repeats itself over and over again, often with major psychological and physical results.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Although some people eat too little, eating too much is also a major problem. Obesity is a medical condition in which so much excess body fat has accumulated in the body that it begins to have an adverse impact on health. In addition to causing people to be stereotyped and treated less positively by others (Crandall, Merman, & Hebl, 2009), uncontrolled obesity leads to health problems including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, sleep apnea, arthritis, Alzheimer’s disease, and some types of cancer (Gustafson, Rothenberg, Blennow, Steen, & Skoog, 2003). Obesity also reduces life expectancy (Haslam & James, 2005). Obesity is determined by calculating the body mass index (BMI), a measurement that compares one’s weight and height. People are defined as overweight when their BMI is greater than 25 kg/m2 and as obese when it is greater than 30 kg/m2. Obesity is a leading cause of death worldwide. Its prevalence is rapidly increasing, and it is one of the most serious public health problems of the 21st century. Although obesity is caused in part by genetics, it is increased by overeating and a lack of physical activity (Nestle & Jacobson, 2000; James, 2008).

Crandall, C. S. (1988). Social contagion of binge eating. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 55(4), 588–598.

Crandall, C. S., Merman, A., & Hebl, M. (2009). Anti-fat prejudice. In T. D. Nelson (Ed.), Handbook of prejudice, stereotyping, and discrimination (pp. 469–487). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Guisinger, S. (2008). Competing paradigms for anorexia nervosa. American Psychologist, 63(3), 199–200.

Gustafson, D., Rothenberg, E., Blennow, K., Steen, B., & Skoog, I. (2003). An 18-year follow-up of overweight and risk of Alzheimer disease. Archives of Internal Medicine, 163(13), 1524.

Haslam, D. W., & James, W. P. (2005). Obesity. Lancet, 366(9492), 197–209. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67483-1

Hoek, H. W., & van Hoeken, D. (2003). Review of the prevalence and incidence of eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 34(4), 383–396; Patrick, L. (2002). Eating disorders: A review of the literature with emphasis on medical complications and clinical nutrition. Alternative Medicine Review, 7(3), 184–202.

Klump, K. L., Burt, S. A., McGue, M., & Iacono, W. G. (2007). Changes in genetic and environmental influences on disordered eating across adolescence: A longitudinal twin study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64(12), 1409–1415.

Nestle, M., & Jacobson, M. F. (2000). Halting the obesity epidemic: A public health policy approach. Public Health Reports, 115(1), 12–24. doi:10.1093/phr/115.1.12; James, W. P. (2008). The fundamental drivers of the obesity epidemic. Obesity Review, 9(Suppl. 1), 6–13; Stroebe, W., van Koningsbruggen, G. M., Papies, E. K., & Aarts, H. (2012). Why most dieters fail but some succeed: A goal conflict model of eating behavior. Psychological Review, 120(1): 110–138. doi:10.1037/a0030849.

Norton, K. I., Olds, T. S., Olive, S., & Dank, S. (1996). Ken and Barbie at life size. Sex Roles, 34(3–4), 287–294.

Rozin, P., Dow, S., Moscovitch, M., & Rajaram, S. (1998). What causes humans to begin and end a meal? A role for memory for what has been eaten, as evidenced by a study of multiple meal eating in amnesic patients. Psychological Science, 9(5), 392–396.

Schachter, S. (1968). Obesity and eating. Science, 161(3843), 751–756.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Vohs, K. D., Voelz, Z. R., Pettit, J. W., Bardone, A. M., Katz, J., Abramson, L. Y.,…Joiner, T. E., Jr. (2001). Perfectionism, body dissatisfaction, and self-esteem: An interactive model of bulimic symptom development. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 20(4), 476–497.

Wolf, G., & Miller, N. E. (1964). Lateral hypothalamic lesions: Effects on drinking elicited by carbachol in preoptic area and posterior hypothalamus. Science, 143(Whole No. 3606), 585–587.

Somatic Symptom and Related Disorders, Sexual Disorders, and Eating Disorders-Video

Khanacademymedicine. (2015, July 20). Somatic symptom disorder and other disorders [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8G5WFKUzvA8. Standard YouTube license.

Mary Shuttlesworth. (2013, April 30). Sexual disorders paraphilia [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dvQ7smKTKmgStandard YouTube license.

CrashCourse. (2014, October 6). Eating and body dysmorphic disorders: Crash course psychology #33. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eMVyZ6Ax-74&t=303s. Standard YouTube License.

Summary

Somatic symptom disorders refer to psychological disorders in which a person experiences numerous long-lasting but seemingly unrelated physical ailments that have no identifiable physical cause. Patients with factitious disorder fake physical symptoms in large part because they enjoy the attention and treatment that they receive in the hospital.

Sexual disorders refer to a variety of problems revolving around performing or enjoying sex. Sexual dysfunctions include problems relating to loss of sexual desire, sexual response or orgasm, and pain during sex. Gender identity disorder (GID, also called transsexualism) is diagnosed when the individual displays a repeated and strong desire to be the other sex, a persistent discomfort with one’s sex, and a belief that one was born the wrong sex, accompanied by significant dysfunction and distress. The classification of GID as a mental disorder has been challenged because people who suffer from GID do not regard their own cross-gender feelings and behaviors as a disorder and do not feel that they are distressed or dysfunctional. A paraphilia is a sexual deviation where sexual arousal is obtained from a consistent pattern of inappropriate responses to objects or people, and in which the behaviors associated with the feelings are distressing and dysfunctional.

Eating disorders include anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa and they affect more than 10 million people (mostly women) in the United States alone. Anorexia nervosa is an eating disorder characterized by extremely low body weight, distorted body image, and an obsessive fear of gaining weight. Often times, anorexia begins with a severe weight loss diet and develops into a preoccupation with food and dieting. Bulimia nervosa is an eating disorder characterized by binge eating followed by purging. Obesity is a medical condition in which so much excess body fat has accumulated in the body that it begins to have an adverse impact on a person’s heath. Uncontrolled obesity leads to health problems including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, sleep apnea, arthritis, and some types of cancer.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.