Substance Use Disorders and Psychosis

Introduction

In this section we will focus on substance use disorders. This diagnostic category in the DSM-5 measures substance use on a continuum from mild to severe. Aside from caffeine, each substance is labeled as its own diagnosis, such as Alcohol Use Disorder. Psychoactive drugs are chemicals that change our states of consciousness, and particularly our perceptions and moods. Consciousness is defined as our subjective awareness of ourselves and our environment. The use (especially in combination) of psychoactive drugs has the potential to create very negative side effects, including tolerance, dependence, withdrawal symptoms, and addiction. In this section we will cover the four primary classes of psychoactive drugs, including stimulants, depressants, opioids, and hallucinogens. We will explore why even though we know the potential costs of using drugs, people continue to engage in using them anyway. (Stangor, 2017)

Later in this section we will discuss schizophrenia spectrum disorders and psychosis. Schizophrenia and the other psychotic disorders are some of the most impairing forms of psychopathology, frequently associated with a profound negative effect on the individual’s educational, occupational, and social function. Sadly, these disorders often manifest right at time of the transition from adolescence to adulthood, just as young people should be evolving into independent young adults. The spectrum of psychotic disorders includes schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder, schizotypal personality disorder, schizophreniform disorder, brief psychotic disorder, as well as psychosis associated with substance use or medical conditions. In this section, we summarize the primary clinical features of these disorders, describe the known cognitive and neurobiological changes associated with schizophrenia, describe potential risk factors and/or causes for the development of schizophrenia, and describe currently available treatments for schizophrenia (Barch, 2018).

Barch, D. M. (2018). Schizophrenia spectrum disorders. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. DOI: nobaproject.com. Retrieved from http://nobaproject.com/modules/schizophrenia-spectrum-disorders?r=NDQ4NDEsNTIyMDE%3D. Licensed under CC BY-NC-SA-4.0.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Substance Use Disorders and Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders

Substance Use Disorders

Altering Consciousness with Psychoactive Drugs

A psychoactive drug is a chemical that changes our states of consciousness, and particularly our perceptions and moods. These drugs are commonly found in everyday foods and beverages, including chocolate, coffee, and soft drinks, as well as in alcohol and in over-the-counter drugs, such as aspirin, Tylenol, and cold and cough medications. Psychoactive drugs are also frequently prescribed as sleeping pills, tranquilizers, and anti-anxiety medications, and they may be taken illegally for recreational purposes. The four primary classes of psychoactive drugs are stimulants, depressants, opioids, and hallucinogens.

Psychoactive drugs affect consciousness by influencing how neurotransmitters operate at the synapses of the central nervous system (CNS). Some psychoactive drugs are agonists, which mimic the operation of a neurotransmitter; some are antagonists, which block the action of a neurotransmitter; and some work by blocking the reuptake of neurotransmitters at the synapse.

The use of psychoactive drugs, and especially those that are used illegally, has the potential to create very negative side effects. This does not mean that all drugs are dangerous, but rather that all drugs can be dangerous, particularly if they are used regularly and over long periods of time. Psychoactive drugs create negative effects not so much through their initial use but through the continued use, accompanied by increasing doses, that ultimately may lead to drug abuse.

The problem is that many drugs create tolerance: an increase in the dose required to produce the same effect, which makes it necessary for the user to increase the dosage or the number of times per day that the drug is taken. As the use of the drug increases, the user may develop dependence, defined as a need to use a drug or other substance regularly. Dependence can be psychological, in which the drug is desired and has become part of the everyday life of the user, but no serious physical effects result if the drug is not obtained; or physical, in which serious physical and mental effects appear when the drug is withdrawn. Cigarette smokers who try to quit, for example, experience physical withdrawal symptoms, such as becoming tired and irritable, as well as extreme psychological cravings to enjoy a cigarette in particular situations, such as after a meal or when they are with friends.

Users may wish to stop using the drug, but when they reduce their dosage they experience withdrawal—negative experiences that accompany reducing or stopping drug use, including physical pain and other symptoms. When the user powerfully craves the drug and is driven to seek it out, over and over again, no matter what the physical, social, financial, and legal cost, we say that he or she has developed an addiction to the drug.

It is a common belief that addiction is an overwhelming, irresistibly powerful force, and that withdrawal from drugs is always an unbearably painful experience. But the reality is more complicated and in many cases less extreme. For one, even drugs that we do not generally think of as being addictive, such as caffeine, nicotine, and alcohol, can be very difficult to quit using, at least for some people. On the other hand, drugs that are normally associated with addiction, including amphetamines, cocaine, and heroin, do not immediately create addiction in their users. Even for a highly addictive drug like cocaine, only about 15% of users become addicted (Robinson & Berridge, 2003; Wagner & Anthony, 2002).

Furthermore, the rate of addiction is lower for those who are taking drugs for medical reasons than for those who are using drugs recreationally. Patients who have become physically dependent on morphine administered during the course of medical treatment for a painful injury or disease are able to be rapidly weaned off the drug afterward, without becoming addicts. Robins, Davis, and Goodwin (1974) found that the majority of soldiers who had become addicted to morphine while overseas were quickly able to stop using after returning home.

This does not mean that using recreational drugs is not dangerous. For people who do become addicted to drugs, the success rate of recovery is low. These drugs are generally illegal and carry with them potential criminal consequences if one is caught and arrested. Drugs that are smoked may produce throat and lung cancers and other problems. Snorting (“sniffing”) drugs can lead to a loss of the sense of smell, nosebleeds, difficulty in swallowing, hoarseness, and chronic runny nose. Injecting drugs intravenously carries with it the risk of contracting infections such as hepatitis and HIV. Furthermore, the quality and contents of illegal drugs are generally unknown, and the doses can vary substantially from purchase to purchase. The drugs may also contain toxic chemicals.

Another problem is the unintended consequences of combining drugs, which can produce serious side effects. Combining drugs is dangerous because their combined effects on the CNS can increase dramatically and can lead to accidental or even deliberate overdoses. For instance, ingesting alcohol or benzodiazepines along with the usual dose of heroin is a frequent cause of overdose deaths in opiate addicts, and combining alcohol and cocaine can have a dangerous impact on the cardiovascular system (McCance-Katz, Kosten, & Jatlow, 1998).

Speeding Up the Brain with Stimulants: Caffeine, Nicotine, Cocaine, and Amphetamines

A stimulant is a psychoactive drug that operates by blocking the reuptake of dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin in the synapses of the CNS. Because more of these neurotransmitters remain active in the brain, the result is an increase in the activity of the sympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system (ANS). Effects of stimulants include increased heart and breathing rates, pupil dilation, and increases in blood sugar accompanied by decreases in appetite. For these reasons, stimulants are frequently used to help people stay awake and to control weight. Used in moderation, some stimulants may increase alertness, but used in an irresponsible fashion they can quickly create dependency. A major problem is the “crash” that results when the drug loses its effectiveness and the activity of the neurotransmitters returns to normal. The withdrawal from stimulants can create profound depression and lead to an intense desire to repeat the high.

Caffeine is a bitter psychoactive drug found in the beans, leaves, and fruits of plants, where it acts as a natural pesticide. It is found in a wide variety of products, including coffee, tea, soft drinks, candy, and desserts. In North America, more than 80% of adults consume caffeine daily (Lovett, 2005). Caffeine acts as a mood enhancer and provides energy. Although the U.S. Food and Drug Administration lists caffeine as a safe food substance, it has at least some characteristics of dependence. People who reduce their caffeine intake often report being irritable, restless, and drowsy, as well as experiencing strong headaches, and these withdrawal symptoms may last up to a week. Most experts feel that using small amounts of caffeine during pregnancy is safe, but larger amounts of caffeine can be harmful to the fetus (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2007).

Nicotine is a psychoactive drug found in the nightshade family of plants, where it acts as a natural pesticide. Nicotine is the main cause for the dependence-forming properties of tobacco use, and tobacco use is a major health threat. Nicotine creates both psychological and physical addiction, and it is one of the hardest addictions to break. Nicotine content in cigarettes has slowly increased over the years, making quitting smoking more and more difficult. Nicotine is also found in smokeless (chewing) tobacco. People who want to quit smoking sometimes use other drugs to help them. For instance, the prescription drug Chantix acts as an antagonist, binding to nicotine receptors in the synapse, which prevents users from receiving the normal stimulant effect when they smoke. At the same time, the drug also releases dopamine, the reward neurotransmitter. In this way Chantix dampens nicotine withdrawal symptoms and cravings. In many cases people are able to get past the physical dependence, allowing them to quit smoking at least temporarily. In the long run, however; the psychological enjoyment of smoking may lead to relapse.

Cocaine is an addictive drug obtained from the leaves of the coca plant. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it was a primary constituent in many popular tonics and elixirs and, although it was removed in 1905, was one of the original ingredients in Coca-Cola. Today, cocaine is taken illegally as a recreational drug.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Cocaine has a variety of adverse effects on the body. It constricts blood vessels, dilates pupils, and increases body temperature, heart rate, and blood pressure. It can cause headaches, abdominal pain, and nausea. Since cocaine also tends to decrease appetite, chronic users may also become malnourished. The intensity and duration of cocaine’s effects, which include increased energy and reduced fatigue, depend on how the drug is taken. The faster the drug is absorbed into the bloodstream and delivered to the brain, the more intense the high. Injecting or smoking cocaine produces a faster, stronger high than snorting it. However, the faster the drug is absorbed, the faster the effects subside. The high from snorting cocaine may last 30 minutes, whereas the high from smoking “crack” cocaine may last only 10 minutes. In order to sustain the high, the user must administer the drug again, which may lead to frequent use, often in higher doses, over a short period of time (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2009).

Amphetamine is a stimulant that produces increased wakefulness and focus, along with decreased fatigue and appetite. Amphetamine is used in prescription medications to treat attention deficit disorder (ADD) and narcolepsy, and to control appetite. Some brand names of amphetamines are Adderall, Benzedrine, Dexedrine, and Vyvanse. But amphetamine (“speed”) is also used illegally as a recreational drug. The methylated version of amphetamine, methamphetamine (“meth” or “crank”), is currently favored by users, partly because it is available in ampoules ready for use by injection (Csaky & Barnes, 1984).

Amphetamines may produce a very high level of tolerance, leading users to increase their intake, often in “jolts” taken every half hour or so. Although the level of physical dependency is small, amphetamines may produce very strong psychological dependence, effectively amounting to addiction. Continued use of stimulants may result in severe psychological depression. The effects of the stimulant methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), also known as “Ecstasy,” provide a good example. MDMA is a very strong stimulant that very successfully prevents the reuptake of serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine. It is so effective that when used repeatedly it can seriously deplete the amount of neurotransmitters available in the brain, producing a catastrophic mental and physical “crash” resulting in serious, long-lasting depression. MDMA also affects the temperature-regulating mechanisms of the brain, so in high doses, and especially when combined with vigorous physical activity like dancing, can cause the body to become so drastically overheated that users can literally “burn up” and die from hyperthermia and dehydration.

Csaky, T. Z., & Barnes, B. A. (1984). Cutting’s handbook of pharmacology (7th ed.). East Norwalk, CT: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Lovett, R. (2005, September 24). Coffee: The demon drink? New Scientist, 2518. Retrieved from http://www.newscientist.com/article.ns?id=mg18725181.700

McCance-Katz, E., Kosten, T., & Jatlow, P. (1998). Concurrent use of cocaine and alcohol is more potent and potentially more toxic than use of either alone—A multiple-dose study 1. Biological Psychiatry, 44(4), 250–259.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2009). Cocaine abuse and addiction. Retrieved from http://www.nida.nih.gov/researchreports/cocaine/cocaine.html

Robins, L. N., Davis, D. H., & Goodwin, D. W. (1974). Drug use by U.S. Army enlisted men in Vietnam: A follow-up on their return home. American Journal of Epidemiology, 99, 235–249.

Robinson, T. E., & Berridge, K. C. (2003). Addiction. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 25–53; Wagner, F. A., & Anthony, J. C. (2002). From first drug use to drug dependence: Developmental periods of risk for dependence upon marijuana, cocaine, and alcohol. Neuropsychopharmacology, 26(4), 479–488.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2007). Medicines in my home: Caffeine and your body. Retrieved from http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/BuyingUsingMedicineSafely/UnderstandingOver-the-CounterMedicines/UCM205286.pdf

Slowing Down the Brain with Depressants: Alcohol, Barbiturates and Benzodiazepines, and Toxic Inhalants

In contrast to stimulants, which work to increase neural activity, a depressant acts to slow down consciousness. A depressant is a psychoactive drug that reduces the activity of the CNS. Depressants are widely used as prescription medicines to relieve pain, to lower heart rate and respiration, and as anticonvulsants. Depressants change consciousness by increasing the production of the neurotransmitter GABA and decreasing the production of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, usually at the level of the thalamus and the reticular formation. The outcome of depressant use (similar to the effects of sleep) is a reduction in the transmission of impulses from the lower brain to the cortex (Csaky & Barnes, 1984).

The most commonly used of the depressants is alcohol, a colorless liquid, produced by the fermentation of sugar or starch, which is the intoxicating agent in fermented drinks. Alcohol is the oldest and most widely used drug of abuse in the world. In low to moderate doses, alcohol first acts to remove social inhibitions by slowing activity in the sympathetic nervous system. In higher doses, alcohol acts on the cerebellum to interfere with coordination and balance, producing the staggering gait of drunkenness. At high blood levels, further CNS depression leads to dizziness, nausea, and eventually a loss of consciousness. High enough blood levels, such as those produced by “guzzling” large amounts of hard liquor at parties, can be fatal.

Alcohol use is highly costly to societies because so many people abuse alcohol and when they do, their judgment after drinking can be substantially impaired. It is estimated that almost half of automobile fatalities are caused by alcohol use, and excessive alcohol consumption is involved in a majority of violent crimes, including rape and murder (Abbey, Ross, McDuffie, & McAuslan, 1996). Alcohol increases the likelihood that people will respond aggressively to provocations (Bushman, 1993, 1997; Graham, Osgood, Wells, & Stockwell, 2006). Even people who are not normally aggressive may react with aggression when they are intoxicated.

“A Sea of Empties.” Retrieved from https://www.flickr.com/photos/theskywatcher/2466121364. Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Alcohol increases aggression because it reduces the ability of the person who has consumed it to inhibit his or her aggression (Steele & Southwick, 1985). When people are intoxicated, they become more self-focused and less aware of the social situation. As a result, they become less likely to notice the social constraints that normally prevent them from engaging aggressively, and are less likely to use those social constraints to guide them. For instance, we might normally notice the presence of a police officer or other people around us, which would remind us that being aggressive is not appropriate. But when we are drunk, we are less likely to be so aware. The narrowing of attention that occurs when we are intoxicated also prevents us from being cognizant of the negative outcomes of our aggression. When we are sober, we realize that being aggressive may produce retaliation, as well as cause a host of other problems. However, we are less likely to realize these potential consequences when we have been drinking (Bushman & Cooper, 1990).

Barbiturates are depressants that are commonly prescribed as sleeping pills and painkillers. Brand names include Luminal (Phenobarbital), Mebaraland, Nembutal, Seconal, and Sombulex. In small to moderate doses, barbiturates produce relaxation and sleepiness, but in higher doses symptoms may include sluggishness, difficulty in thinking, slowness of speech, drowsiness, faulty judgment, and eventually coma or even death (Medline Plus, 2008).

Related to barbiturates, benzodiazepines are a family of depressants used to treat anxiety, insomnia, seizures, and muscle spasms. In low doses, they produce mild sedation and relieve anxiety; in high doses, they induce sleep. In the United States, benzodiazepines are among the most widely prescribed medications that affect the CNS. Brand names include Centrax, Dalmane, Doral, Halcion, Librium, ProSom, Restoril, Xanax, and Valium.

Abbey, A., Ross, L. T., McDuffie, D., & McAuslan, P. (1996). Alcohol and dating risk factors for sexual assault among college women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 20(1), 147–169.

Bushman, B. J. (1993). Human aggression while under the influence of alcohol and other drugs: An integrative research review. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 2(5), 148–152; Bushman, B. J. (Ed.). (1997). Effects of alcohol on human aggression: Validity of proposed explanations. New York, NY: Plenum Press; Graham, K., Osgood, D. W., Wells, S., & Stockwell, T. (2006). To what extent is intoxication associated with aggression in bars? A multilevel analysis. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 67(3), 382–390.

Bushman, B. J., & Cooper, H. M. (1990). Effects of alcohol on human aggression: An integrative research review. Psychological Bulletin, 107(3), 341–354.

Csaky, T. Z., & Barnes, B. A. (1984). Cutting’s handbook of pharmacology (7th ed.). East Norwalk, CT: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Medline Plus. (2008). Barbiturate intoxication and overdose. Retrieved from http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/000951.htm

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Steele, C. M., & Southwick, L. (1985). Alcohol and social behavior: I. The psychology of drunken excess. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48(1), 18–34.

Opioids: Opium, Morphine, Heroin, and Codeine

Opioids are chemicals that increase activity in opioid receptor neurons in the brain and in the digestive system, producing euphoria, analgesia, slower breathing, and constipation. Their chemical makeup is similar to the endorphins, the neurotransmitters that serve as the body’s “natural pain reducers.” Natural opioids are derived from the opium poppy, which is widespread in Eurasia, but they can also be created synthetically.

Opium is the dried juice of the unripe seed capsule of the opium poppy. It may be the oldest drug on record, known to the Sumerians before 4000 BC. Morphine and heroin are stronger, more addictive drugs derived from opium, while codeine is a weaker analgesic and less addictive member of the opiate family. When morphine was first refined from opium in the early 19th century, it was touted as a cure for opium addiction, but it didn’t take long to discover that it was actually more addicting than raw opium. When heroin was produced a few decades later, it was also initially thought to be a more potent, less addictive painkiller but was soon found to be much more addictive than morphine. Heroin is about twice as addictive as morphine, and creates severe tolerance, moderate physical dependence, and severe psychological dependence.

The opioids activate the sympathetic division of the ANS, causing blood pressure and heart rate to increase, often to dangerous levels that can lead to heart attack or stroke. At the same time the drugs also influence the parasympathetic division, leading to constipation and other negative side effects. Symptoms of opioid withdrawal include diarrhea, insomnia, restlessness, irritability, and vomiting, all accompanied by a strong craving for the drug. The powerful psychological dependence of the opioids and the severe effects of withdrawal make it very difficult for morphine and heroin abusers to quit using. In addition, because many users take these drugs intravenously and share contaminated needles, they run a very high risk of being infected with diseases. Opioid addicts suffer a high rate of infections such as HIV, pericarditis (an infection of the membrane around the heart), and hepatitis B, any of which can be fatal.

Source: Courtesy of BBC News, http://news.bbc.co.uk/olmedia/855000/images/_855018_inject300.jpgStangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Hallucinogens: Cannabis, Mescaline, and LSD

The drugs that produce the most extreme alteration of consciousness are the hallucinogens, psychoactive drugs that alter sensation and perception and that may create hallucinations. The hallucinogens are frequently known as “psychedelics.” Drugs in this class include lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD, or “Acid”), mescaline, and phencyclidine (PCP), as well as a number of natural plants including cannabis (marijuana), peyote, and psilocybin. The chemical compositions of the hallucinogens are similar to the neurotransmitters serotonin and epinephrine, and they act primarily as agonists by mimicking the action of serotonin at the synapses. The hallucinogens may produce striking changes in perception through one or more of the senses. The precise effects a user experiences are a function not only of the drug itself but also of the user’s preexisting mental state and expectations of the drug experience. The hallucinations that may be experienced when taking these drugs are strikingly different from everyday experience and frequently are more similar to dreams than to everyday consciousness.

Cannabis (marijuana) is the most widely used hallucinogen. Until it was banned in the United States under the Marijuana Tax Act of 1938, it was widely used for medical purposes. In recent years, cannabis has again been frequently prescribed for the treatment of pain and nausea, particularly in cancer sufferers, as well as for a wide variety of other physical and psychological disorders (Ben Amar, 2006). While medical marijuana is now legal in several American states, it is still banned under federal law, putting those states in conflict with the federal government. Marijuana also acts as a stimulant, producing giggling, laughing, and mild intoxication. It acts to enhance perception of sights, sounds, and smells, and may produce a sensation of time slowing down. It is much less likely to lead to antisocial acts than that other popular intoxicant, alcohol, and it is also the one psychedelic drug whose use has not declined in recent years (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2009).

Ben Amar, M. (2006). Cannabinoids in medicine: A review of their therapeutic potential. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 105, 1–25.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2009). NIDA InfoFacts: High School and Youth Trends. Retrieved from http://www.drugabuse.gov/infofacts/HSYouthTrends.html.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Why We Use Psychoactive Drugs

People have used, and often abused, psychoactive drugs for thousands of years. Perhaps this should not be surprising, because many people find using drugs to be fun and enjoyable. Even when we know the potential costs of using drugs, we may engage in them anyway because the pleasures of using the drugs are occurring right now, whereas the potential costs are abstract and occur in the future.

Individual ambitions, expectations, and values also influence drug use. Vaughan, Corbin, and Fromme (2009) found that college students who expressed positive academic values and strong ambitions had less alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems, and cigarette smoking has declined more among youth from wealthier and more educated homes than among those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2004).

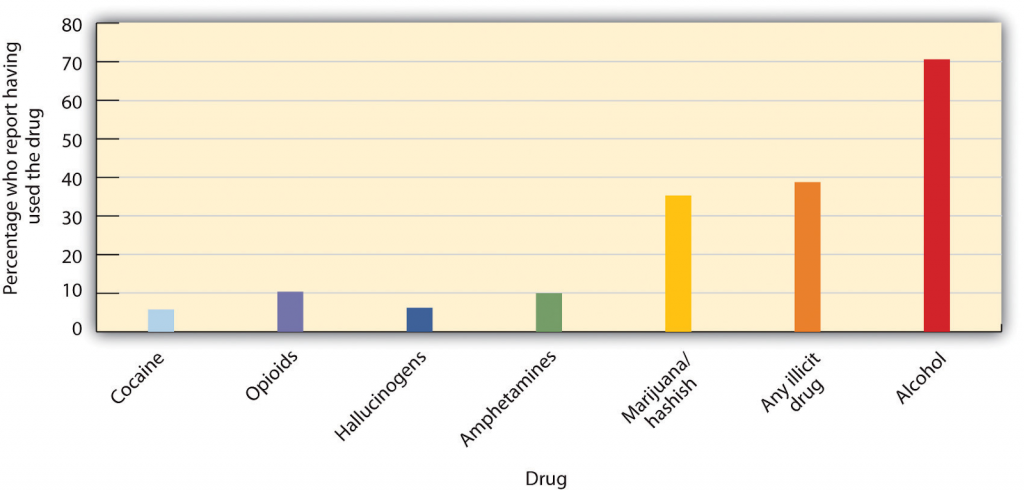

Drug use is, in part, the result of socialization. Children try drugs when their friends convince them to do it, and these decisions are based on social norms about the risks and benefits of various drugs. In the period 1991 to 1997, the percentage of 12th-graders who responded that they perceived “great harm in regular marijuana use” declined from 79% to 58%, while annual use of marijuana in this group rose from 24% to 39% (Johnston et al., 2004). And students sometimes binge drink when they see that many other people around them are also binging (Clapp, Reed, Holmes, Lange, & Voas, 2006).

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Clapp, J., Reed, M., Holmes, M., Lange, J., & Voas, R. (2006). Drunk in public, drunk in private: The relationship between college students, drinking environments and alcohol consumption. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 32(2), 275–285.

Johnston, L. D., O’Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. G., & Schulenberg, J. E. (2004). Monitoring the future: National results on adolescent drug use. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan (conducted for the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institute of Health)

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Vaughan, E. L., Corbin, W. R., & Fromme, K. (2009). Academic and social motives and drinking behavior. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 23(4), 564–576.

Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders and Psychosis

The term schizophrenia, which in Greek means “split mind,” was first used to describe a psychological disorder by Eugen Bleuler (1857–1939), a Swiss psychiatrist who was studying patients who had very severe thought disorders. The patients in his clinic often echoed other people’s speech, stopped in the middle of their sentences, were unable to complete a train of thought, and were generally incoherent. Schizophrenia is a serious psychological disorder marked by delusions, hallucinations, loss of contact with reality, inappropriate affect, disorganized speech, social withdrawal, and deterioration of adaptive behavior.

Schizophrenia is the most chronic and debilitating of all psychological disorders. It affects men and women equally, occurs in similar rates across ethnicities and across cultures, and affects at any one time approximately 3 million people in the United States (National Institute of Mental Health, 2010). Schizophrenia is most commonly diagnosed in teenagers and young adults—usually between the ages of 16 and 30 and rarely after the age of 45 or in children (Mueser & McGurk, 2004; Nicholson, Lenane, Hamburger, Fernandez, Bedwell, & Rapoport, 2000).

Symptoms of Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is accompanied by a variety of symptoms, but not all patients have all of them (Lindenmayer & Khan, 2006). The symptoms are divided into positive symptoms, negative symptoms, and cognitive symptoms (American Psychiatric Association, 2008; National Institute of Mental Health, 2010). Positive symptoms refer to the presence of abnormal behaviors or experiences (such as hallucinations) that are not observed in normal people, whereas negative symptoms (such as lack of affect and an inability to socialize with others) refer to the loss or deterioration of thoughts and behaviors that are typical of normal functioning. Finally, cognitive symptoms are the changes in cognitive processes that accompany schizophrenia (Skrabalo, 2000). Because the patient has lost contact with reality, we say that he or she is experiencing psychosis, which is a psychological condition characterized by a loss of contact with reality.

| Positive Symptoms | Negative Symptoms | Cognitive Symptoms |

| Hallucinations | Social withdrawal | Poor executive control |

| Delusions (of grandeur or persecution) | Flat affect and lack of pleasure in everyday life | Trouble focusing |

| Derailment | Apathy and loss of motivation | Working memory problems |

| Grossly disorganize behavior | Distorted sense of time | Poor problem-solving abilities |

| Inappropriate affect | Lack of goal-oriented activity | |

| Movement disorders | Limited speech | |

| Poor hygiene and grooming |

Chart: Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

People with schizophrenia almost always suffer from hallucinations—imaginary sensations that occur in the absence of a real stimulus or that are gross distortions of a real stimulus. Auditory hallucinations are the most common and are reported by approximately three quarters of patients (Nicolson, Mayberg, Pennell, & Nemeroff, 2006). Patients with schizophrenia frequently report hearing imaginary voices that curse them, comment on their behavior, order them to do things, or warn them of danger (National Institute of Mental Health, 2009). Visual hallucinations are less common and frequently involve seeing God or the devil (De Sousa, 2007).

Schizophrenic people also commonly experience delusions, which are false beliefs not commonly shared by others within one’s culture, and maintained even though they are obviously out of touch with reality. People with delusions of grandeur believe that they are important, famous, or powerful. They often become convinced that they are someone else, such as the king, the president or God, or that they have some special talent or ability. Some claim to have been assigned to a special covert mission (Buchanan & Carpenter, 2005). People with delusions of persecution believe that a person or group seeks to harm them. They may think that people are able to read their minds and control their thoughts (Maher, 2001). If a person suffers from delusions of persecution, there is a good chance that he or she will become violent, and this violence is typically directed at family members (Buchanan & Carpenter, 2005).

Retrieved from https://www.flickr.com/photos/irreparable_adulation/3866927302. Licensed under CC BY-2.0.

People suffering from schizophrenia also often suffer from the positive symptom of derailment—the shifting from one subject to another, without following any one line of thought to conclusion—and may exhibit grossly disorganized behavior including inappropriate sexual behavior, peculiar appearance and dress, unusual agitation (e.g., shouting and swearing), strange body movements, and awkward facial expressions. It is also common for schizophrenia sufferers to experience inappropriate affect. For example, a patient may laugh uncontrollably when hearing sad news. Movement disorders typically appear as agitated movements, such as repeating a certain motion again and again, but can in some cases include catatonia, a state in which a person does not move and is unresponsive to others (Janno, Holi, Tuisku, & Wahlbeck, 2004; Rosebush & Mazurek, 2010).

Negative symptoms of schizophrenia include social withdrawal, poor hygiene and grooming, poor problem-solving abilities, and a distorted sense of time (Skrabalo, 2000). Patients often suffer from flat affect, which means that they express almost no emotional response (e.g., they speak in a monotone and have a blank facial expression) even though they may report feeling emotions (Kring, 1999). Another negative symptom is the tendency toward incoherent language, for instance, to repeat the speech of others (“echo speech”). Some schizophrenics experience motor disturbances, ranging from complete catatonia and apparent obliviousness to their environment to random and frenzied motor activity during which they become hyperactive and incoherent (Kirkpatrick & Tek, 2005).

Not all schizophrenic patients exhibit negative symptoms, but those who do also tend to have the poorest outcomes (Fenton & McGlashan, 1994). Negative symptoms are predictors of deteriorated functioning in everyday life and often make it impossible for sufferers to work or to care for themselves.

Cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia are typically difficult for outsiders to recognize but make it extremely difficult for the sufferer to lead a normal life. These symptoms include difficulty comprehending information and using it to make decisions (the lack of executive control), difficulty maintaining focus and attention, and problems with working memory (the ability to use information immediately after it is learned).

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.). Washington, DC: Author; National Institute of Mental Health. (2010, April 26). What is schizophrenia? Retrieved from http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/schizophrenia/index.shtml.

Buchanan, R. W., & Carpenter, W. T. (2005). Concept of schizophrenia. In B. J. Sadock & V. A. Sadock (Eds.), Kaplan & Sadock’s comprehensive textbook of psychiatry. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

De Sousa, A. (2007). Types and contents of hallucinations in schizophrenia. Journal of Pakistan Psychiatric Society, 4(1), 29.

Fenton, W. S., & McGlashan, T. H. (1994). Antecedents, symptom progression, and long-term outcome of the deficit syndrome in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry, 151, 351–356.

Janno, S., Holi, M., Tuisku, K., & Wahlbeck, K. (2004). Prevalence of neuroleptic-induced movement disorders in chronic schizophrenia patients. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161, 160–163; Rosebush, P. I., & Mazurek, M. F. (2010). Catatonia and its treatment. Schizophrenia Bulleting, 36(2), 239–242. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbp141.

Kirkpatrick, B., & Tek, C. (2005). Schizophrenia: Clinical features and psychological disorder concepts. In B. J. Sadock & S. V. Sadock (Eds.), Kaplan & Sadock’s comprehensive textbook of psychiatry (pp. 1416–1435). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Kring, A. M. (1999). Emotion in schizophrenia: Old mystery, new understanding. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 8, 160–163.

Lindenmayer, J. P., & Khan, A. (2006). Psychological disorder. In J. A. Lieberman, T. S. Stroup, & D. O. Perkins (Eds.), Textbook of schizophrenia (pp. 187–222). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Maher, B. A. (2001). Delusions. In P. B. Sutker & H. E. Adams (Eds.), Comprehensive handbook of psychological disorder (3rd ed., pp. 309–370). New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum.

Mueser, K. T., & McGurk, S. R. (2004). Schizophrenia. Lancet, 363(9426), 2063–2072; Nicolson, R., Lenane, M., Hamburger, S. D., Fernandez, T., Bedwell, J., & Rapoport, J. L. (2000). Lessons from childhood-onset schizophrenia. Brain Research Review, 31(2–3), 147–156.

National Institute of Mental Health. (2009, September 8). What are the symptoms of schizophrenia? Retrieved from http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/schizophrenia/what-are-the-symptoms-of-schizophrenia.shtml.

National Institute of Mental Health. (2010, April 26). What is schizophrenia? Retrieved from http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/schizophrenia/index.shtml.

Nicolson, S. E., Mayberg, H. S., Pennell, P. B., & Nemeroff, C. B. (2006). Persistent auditory hallucinations that are unresponsive to antipsychotic drugs. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 163, 1153–1159. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.7.1153.

Skrabalo, A. (2000). Negative symptoms in schizophrenia(s): The conceptual basis. Harvard Brain, 7, 7–10.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Explaining Schizophrenia

There is no single cause of schizophrenia. Rather, a variety of biological and environmental risk factors interact in a complex way to increase the likelihood that someone might develop schizophrenia (Walker, Kestler, Bollini, & Hochman, 2004). Studies in molecular genetics have not yet identified the particular genes responsible for schizophrenia, but it is evident from research using family, twin, and adoption studies that genetics are important (Walker & Tessner, 2008). The likelihood of developing schizophrenia increases dramatically if a close relative also has the disease.

Neuroimaging studies have found some differences in brain structure between schizophrenic and normal patients. In some people with schizophrenia, the cerebral ventricles (fluid-filled spaces in the brain) are enlarged (Suddath, Christison, Torrey, Casanova, & Weinberger, 1990). People with schizophrenia also frequently show an overall loss of neurons in the cerebral cortex, and some show less activity in the frontal and temporal lobes, which are the areas of the brain involved in language, attention, and memory. This would explain the deterioration of functioning in language and thought processing that is commonly experienced by schizophrenic patients (Galderisi et al., 2008). The rapid changes in brain development that occur during late adolescence seem to be important in the progression of the disease (Rolls & Deco, 2011).

Many researchers believe that schizophrenia is caused, in part, by excess dopamine, and this theory is supported by the fact that most of the drugs useful in treating schizophrenia inhibit dopamine activity in the brain (Javitt & Laruelle, 2006). Levels of serotonin may also play a part (Inayama et al., 1996). But recent evidence suggests that the role of neurotransmitters in schizophrenia is more complicated than was once believed. It also remains unclear whether observed differences in the neurotransmitter systems of people with schizophrenia cause the disease, or if they are the result of the disease itself or its treatment (Csernansky & Grace, 1998).

A genetic predisposition to developing schizophrenia does not always develop into the actual disorder. Even if a person has an identical twin with schizophrenia, he/she still has less than a 50% chance of getting it, and over 60% of all schizophrenic people have no first- or second-degree relatives with schizophrenia (Gottesman & Erlenmeyer-Kimling, 2001; Riley & Kendler, 2005). This suggests that there are important environmental causes as well.

One hypothesis is that schizophrenia is caused, in part, by disruptions to normal brain development in infancy that may be caused by poverty, malnutrition, and disease (Brown et al., 2004; Murray & Bramon, 2005; Susser et al., 1996; Waddington, Lane, Larkin, O’Callaghan, 1999). Stress also increases the likelihood that a person will develop schizophrenic symptoms; onset and relapse of schizophrenia typically occur during periods of increased stress (Walker, Mittal, & Tessner, 2008). However, it may be that people who develop schizophrenia are more vulnerable to stress than others and not necessarily that they experience more stress than others (Walker, Mittal, & Tessner, 2008). Many homeless people are likely to be suffering from undiagnosed schizophrenia.

Another social factor that has been found to be important in schizophrenia is the degree to which one or more of the patient’s relatives is highly critical or highly emotional in their attitude toward the patient. Hooley and Hiller (1998) found that schizophrenic patients who ended a stay in a hospital and returned to a family with high expressed emotion were three times more likely to relapse than patients who returned to a family with low expressed emotion. It may be that the families with high expressed emotion are a source of stress to the patient.

Brown, A. S., Begg, M. D., Gravenstein, S., Schaefer, C. S., Wyatt, R. J., Bresnahan, M.,…Susser, E. S. (2004). Serologic evidence of prenatal influenza in the etiology of schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry, 61, 774–780; Murray, R. M., & Bramon, E. (2005). Developmental model of schizophrenia. In B. J. Sadock & V. A. Sadock (Eds.), Kaplan & Sadock’s comprehensive textbook of psychiatry (pp. 1381–1395). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Susser, E. B., Neugebauer, R., Hock, H.W., Brown, A. S., Lin, S., Labowitz, D., & Gorman, J. M. (1996). Schizophrenia after prenatal famine: Further evidence. Archives of general psychiatry, 53, 25–31; Waddington J. L., Lane, A., Larkin, C., & O’Callaghan, E. (1999). The neurodevelopmental basis of schizophrenia: Clinical clues from cerebro-craniofacial dysmorphogenesis, and the roots of a lifetime trajectory of disease. Biological Psychiatry, 46(1), 31–9.

Csernansky, J. G., & Grace, A. A. (1998). New models of the pathophysiology of schizophrenia: Editors’ introduction. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 24(2), 185–187.

Galderisi, S., Quarantelli, M., Volper, U., Mucci, A., Cassano, G. B., Invernizzi, G.,…Maj, M. (2008). Patterns of structural MRI abnormalities in deficit and nondeficit schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 34, 393–401.

Gottesman, I. I., & Erlenmeyer-Kimling, L. (2001). Family and twin studies as a head start in defining prodomes and endophenotypes for hypothetical early interventions in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research, 5(1), 93–102; Riley, B. P., & Kendler, K. S. (2005). Schizophrenia: Genetics. In B. J. Sadock & V. A. Sadock (Eds.), Kaplan & Sadock’s comprehensive textbook of psychiatry (pp.1354–1370). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Hooley, J. M., & Hiller, J. B. (1998). Expressed emotion and the pathogenesis of relapse in schizophrenia. In M. F. Lenzenweger & R. H. Dworkin (Eds.), Origins and development of schizophrenia: Advances in experimental psychopathology (pp. 447–468). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Inayama, Y., Yoneda, H., Sakai, T., Ishida, T., Nonomura, Y., Kono, Y.,…Asaba, H. (1996). Positive association between a DNA sequence variant in the serotonin 2A receptor gene and schizophrenia. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 67(1), 103–105.

Javitt, D. C., & Laruelle, M. (2006). Neurochemical theories. In J. A. Lieberman, T. S. Stroup, & D. O. Perkins (Eds.), Textbook of schizophrenia (pp. 85–116). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Rolls, E. T., & Deco, G. (2011). A computational neuroscience approach to schizophrenia and its onset. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 35(8), 1644–1653. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.09.001.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.

Suddath, R. L., Christison, G. W., Torrey, E. F., Casanova, M. F., & Weinberger, D. R. (1990). Anatomical abnormalities in the brains of monozygotic twins discordant for schizophrenia. New England Journal of Medicine, 322(12), 789–794.

Walker, E., Kesler, L., Bollini, A., & Hochman, K. (2004). Schizophrenia: Etiology and course. Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 401–430.

Walker, E., Mittal, V., & Tessner, K. (2008). Stress and the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis in the developmental course of schizophrenia. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 4, 189–216.

Walker, E., & Tessner, K. (2008). Schizophrenia. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(1), 30–37.

Substance Use Disorders and Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders

Brooke Miller. (2015, March 28). Classes of psychoactive drugs. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CgeY0IXaVMk. Standard YouTube License.

Osmosis. (2016, March 8). Schizophrenia-causes, symptoms, diagnosis, treatment & pathology. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PURvJV2SMso. Standard YouTube License.

Summary

Psychoactive drugs are chemicals that change our state of consciousness. Psychoactive drugs work by influencing neurotransmitters in the Central Nervous System (CNS). Using psychoactive drugs may create tolerance and, when they are no longer used, withdrawal. Addiction may result from tolerance and the difficulty of withdrawal. Stimulants, including caffeine, nicotine, cocaine, and amphetamine, are psychoactive drugs that operate by blocking the reuptake of dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin in the synapses of the central nervous system (CNS). Depressants, including alcohol, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, and toxic inhalants, reduce the activity of the CNS. Opioids, including opium, morphine, heroin, and codeine, are chemicals that increase activity in opioid receptor neurons in the brain and in the digestive system, producing euphoria, analgesia, slower breathing, and constipation. Hallucinogens, including cannabis, mescaline, and LSD, are psychoactive drugs that alter sensation and perception and may create hallucinations.

Schizophrenia is a serious psychological disorder marked by delusions, hallucinations, loss of contact with reality, inappropriate affect, disorganized speech, social withdrawal, and deterioration of adaptive behavior. About 3 million Americans have schizophrenia. When a schizophrenic patient loses contact with reality, we say that he or she is experiencing psychosis. Positive symptoms of schizophrenia include hallucinations, delusions, derailment, disorganized behavior, inappropriate affect and catatonia. The negative symptoms of schizophrenia include social withdrawal, poor hygiene and grooming, poor problem solving abilities, and a distorted sense of time. Cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia include difficulty comprehending and using information and problems maintaining focus. There is no single cause of schizophrenia. Rather, there are a variety of biological and environmental risk factors that interact in a complex way to increase the likelihood that someone might develop schizophrenia.

Stangor, C. (2017). Introduction to psychology. Boston, MA: Flatworld.