Introduction

The writer Maya Angelou once said, “I find in my poetry and prose the rhythms and imagery of the best – I mean, when I’m at my best – of the good Southern black preachers. The lyricism of the spirituals and the directness of gospel songs and the mystery of blues are in my music or in my poetry and prose, or I missed everything.” Indeed, while many readers probably learn about rhythm from poets, poets learn about rhythm from daily life. The pattern of words, the patterning of sentences, the sounds of spoken speech: poets internalize these rhythms and use them to bring musicality and enhanced meaning to their work.

If you’ve learned about rhythm by studying meter, you may be familiar with terms like stressed and unstressed syllables. While exploring the rhythm of a poem may seem intimidating, it really involves attenuating yourself to the natural ways we speak. With this in mind, you might find yourself thinking, of course. Words are composed of emphasized and unemphasized combinations.

It’s important to keep in mind that, even if a piece of writing does not seem to have a recognizable rhythm, such as iambic pentameter, it might still be a poem. In fact, these days, most poets do not write in metered verse. Instead, like Angelou they elevate the rhythm of spoken or common language.

Rhythm

Stress, Rhythm, & Meter

All speech has rhythm because we naturally stress some words or syllables more than others. The rhythm can sometimes be very regular and pronounced, as in a children’s nursery rhyme – ‘JACK and JILL went UP the HILL’ – but even in the most ordinary sentence the important words are given more stress. In poetry, rhythm is extremely important: patterns are deliberately created and repeated for varying effects.

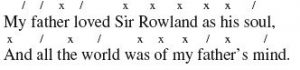

The rhythmical pattern of a poem is called its meter, and we can analyze, or scan lines of poetry to identify stressed and unstressed syllables. In marking the text to show this, the mark ‘/’ is used to indicate a stressed syllable, and ‘x’ to indicate an unstressed syllable. Each complete unit of stressed and unstressed syllables is called a foot, which usually has one stressed and one or two unstressed syllables.

The most common foot in English is known as the iamb, which is an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed one (x /). Many words in English are iambic: a simple example is the word forgot. When we say this, the stresses naturally fall in the sequence:

![]()

Iambic rhythm is in fact the basic sound pattern in ordinary English speech. If you say the following line aloud you will hear what I mean:

![]()

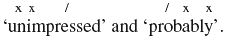

The next most common foot is the trochee, a stressed syllable (or beat) followed by an unstressed one (/x), as in the word

mountain

![]()

Both the iamb and the trochee have two syllables, the iamb being a ‘rising’ rhythm and the trochee a ‘falling’ rhythm. Another two-syllable foot known as the spondee has two equally stressed beats (/ /), as in

Other important feet have three syllables. The most common are the anapest (x x /) and the dactyl (/ x x), which are triple rhythms, rising and falling respectively, as in the words

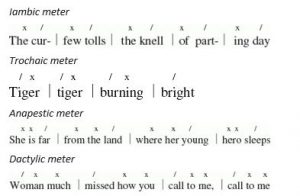

Here are some fairly regular examples of the four main kinds of meter used in poetry. (I have separated the feet by using a vertical slash.) You should say the lines aloud, listening for the stress patterns and noting how the beats fall on particular syllables or words.

The other technical point that you need to know about is the way the lengths of lines of verse are described. This is done according to the number of feet they contain, and the names given to different lengths of lines are as follows:

- monometer- a line of one foot

- dimeter- a line of two feet

- trimeter- a line of three feet

- tetrameter- a line of four feet

- pentameter- a line of five feet

- hexameter- a line of six feet

- heptameter- a line of seven feet

- octameter- a line of eight feet.

By far the most widely used of these are the tetrameter and the pentameter. If you look back at the four lines of poetry given as examples above, you can count the feet. You will see that the first one has five feet, so it is an iambic pentameter line; the second one has four feet, so it is a trochaic tetrameter line; the fourth and fifth also have four feet, so are anapestic and dactylic tetrameter lines respectively. Lines do not always have exactly the ‘right’ number of beats. Sometimes a pentameter line will have an extra beat, as in the famous line from Hamlet, “To be or not to be: that is the question,” where the “tion” of question is an eleventh, unstressed beat. (It is worth asking yourself why Shakespeare wrote the line like this. Why did he not write what would have been a perfectly regular ten-syllable line, such as “The question is, to be or not to be”?)

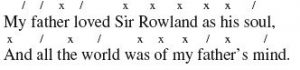

Having outlined some of the basic meters of English poetry, it is important to say at once that very few poems would ever conform to a perfectly regular metrical pattern. The effect of that would be very boring indeed: imagine being restricted to using only iambic words, or trying to keep up a regular trochaic rhythm. Poets therefore often include trochaic or anapestic or dactylic words or phrases within what are basically iambic lines, in order to make them more interesting and suggestive, and to retain normal pronunciation. Here is a brief example from Shakespeare to show you what this mean. These lines were spoken by Rosalind in As You Like It, Act 1, scene 2. This first version has been marked to show you the basic iambic meter.

If you say the lines out loud in this regular way you can hear that the effect is very unnatural. Here is one way the lines might be scanned to show how the stresses would fall in speech (though there are other ways of scanning them):

It must be emphasized that there is no need to feel that you must try to remember all the technical terms in poetry. The purpose has been to help you to become aware of the importance of rhythmic effects in poetry, and it can be just as effective to try to describe these in your own words.

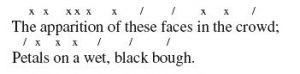

The thing to hang on to when writing about the rhythm of a poem is that, as Ezra Pound put it, “Rhythm MUST have meaning. It can’t be merely a careless dash off with no grip and no real hold to the words and sense, a tumty tum tumpty tum tum ta” (quoted in Gray, 1990, p. 56). There are occasions, of course, when a tum-ty-ty-tum rhythm may be appropriate and have meaning. When Tennyson wrote “The Charge of the Light Brigade,” he recreated the sound, pace, and movement of horses thundering along with the emphatic dactyls of “Half a league, half a league, half a league onward / Into the valley of death rode the six hundred.” For a very different example, look at a short two-line poem by Pound himself. This time there is no fixed meter: like much twentieth century poetry, this poem is in free verse. Its title is “In a Station of the Metro” (the Metro being the Paris underground railway). It was written in 1916:

Here you can see that the rhythm plays a subtle part in conveying the meaning. The poem is comparing the faces of people in a crowded underground to petals that have fallen on to a wet bough. The rhythm not only highlights the key words in each line, but produces much of the emotional feeling of the poem by slowing down the middle words of the first line and the final three words of the second.

Introduction to Literature. Licensed under CC BY SA 4.0 https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-introliterature/chapter/approaching-poetry/

Summary

Rhythm is the sequence of stressed and unstressed syllables within a line of poetry. You might also think of it as the music of the language. Rhythm is the pulse of poetry, its heartbeat. Even when a poem does not use a recognizable meter such as iambic pentameter, it always contains rhythm. That’s because each and every word you or I utter is a combination of stressed and unstressed syllables.