Introduction

Seeing a movie and reading the book it was based on are two very different experiences. Readers of series like Harry Potter, Twilight, or even Game of Thrones, know are familiar with disappointing casting, actor chemistry, or the elimination of storylines altogether to better suit the novels to screen. Even though plays are written for performance, seeing a play and reading the script are also two very different experiences. Although the spoken text stays the same, the performance itself varies based on choices that the actors, director, and designer make based on their interpretation of the text. Everything in a performance is a choice decided on by a group of people coming together to create a production.

As you read, looking for moments where there are possibilities for variation in the performance and think about the variety of choices available and consider the resulting impact of each choice. How does the subtext change based on the choices made by actors, directors, or designers? And what informs each of these choices? You might consider moment from the perspective of each designer: How would the lighting designer interpret the scene–How much light would they use and what color? How would the costume designer understand the scene—What would characters be wearing, what color, and why is it significant, how does it help tell the story? Thinking about all of the different elements and people that unite to create performance and how many different ways there are to read a text for production will certainly help you become better acquainted with thinking about the dramatic text as a performance.

Thinking About Performance

Performance and Production

The idea that drama is a performed art should, by now, be one with which you feel familiar. What should also be clear from each of the examples discussed so far is that there is a range of factors to consider when approaching a dramatic text, and that to engage with any dramatic work we need to consider more than just the words on the page. Here, I’ll be asking you to think about the language of the text, and about what’s involved in moving outwards from the page to the stage. I will also be asking you to begin thinking about the text in relationship to its production and reception. This means acknowledging that the process of moving from the text to the performance involves making decisions about, among other things, delivery, movement, set design, sound, costume and lighting.

The following two extracts are very different; the first is from the Shakespearean tragedy, Macbeth, and the second from Ibsen’s A Doll’s House. Both, however, also contain some similarities in terms of how they suggest performance possibilities. Here they are reproduced without the stage directions. Read the following extracts carefully, noting how the language implies possibilities for performance.

Extract 1

GENTLEWOMAN – Lo you, here she comes. This is her very guise, and upon my life, fast asleep. Observe her, stand close.

DOCTOR – How came she by that light?

GENTLEWOMAN – Why, it stood by her. She has light by her continually, ’tis her command.

DOCTOR – You see her eyes are open.

GENTLEWOMAN – Ay, but their sense are shut.

DOCTOR – What is it she does now? Look how she rubs her hands.

GENTLEWOMAN – It is an accustomed action with her, to seem thus washing her hands; I have known her continue in this a quarter of an hour.

LADY MACBETH – Yet here’s a spot.

DOCTOR – Hark, she speaks.

Extract 2

HELMER – Nora, what do you think I have got here?

NORA – Money!

HELMER – There you are! Do you think I don’t know what a lot is wanted for housekeeping at Christmas time?

NORA – Ten shillings – a pound – two pounds! Thank you, thank you, Torvald; that will keep me going for a long time.

HELMER – Indeed it must.

NORA – Yes, yes, it will. But come here and let me show you what I have bought. And all so cheap! Look, here is a new suit for Ivar and a sword, and a horse and a trumpet for Bob, and a doll and dolly’s bedstead for Emmy -they are very plain, but anyway she will soon break them in pieces. And here are dress lengths and handkerchiefs for the maids; old Anne really ought to have something better.

HELMER – And what is in this parcel?

NORA – No, no! You mustn’t see that till this evening.

There are obvious contrasts between the two extracts, both in the language used and in the way the subject of the dialogue is revealed to us. The first draws us into a dialogue, but one that is highly ambiguous as to its subject, at least at the start. It becomes apparent that this is a scene of voyeurism, in which those watching observe the somnambulant rituals of Lady Macbeth. The second extract presents an altogether more naturalistic scene; here there are identifiable characters, engaged in a dialogue about a discernible subject. There is however a sense in which the language in the two extracts is very similar, and that is in its performative function. Dramatic language often ensures that the dramatic situation is constituted in the speech-act itself; in the Shakespearean and earlier periods the verbal indicators of dramatic action were especially important, given the absence of the visual and technical means of presentation we have today. Here the speech of the Doctor and the Gentlewoman suggests a series of actions carried out by Lady Macbeth (sleepwalking, carrying a light, washing), while the dialogue between Torvald and Nora denotes various actions, gestures and dynamics; the counting of the money, the movement of Torvald towards Nora to look at the presents, and Nora’s display of them, his curiosity in the parcel that Nora then refuses to let him see.

What are some of the implications for the performance of these extracts?

The first extract presents us with a number of performance considerations, the most challenging being how to direct the movement and actions of Lady Macbeth. She is carrying a light and is sleepwalking, so decisions about lighting and costume need to be considered. Does she, for example, occupy the main performance area, with the other characters looking on from the side in hushed conversation? Does she remain standing, or would you want her to be kneeling, perhaps implying remorse or the act of praying? When Roman Polanski directed Francesca Annis in this scene in his 1971 film version of Macbeth, he chose to present her without clothes, thus emphasizing her vulnerability, and in stark contrast to the scores of Lady Macbeths who roam the stage in a nightdress. How would you choose to portray her in this scene?

The second extract depicts a conversation between a husband and wife in an altogether more naturalistic scene, but is nonetheless dramatic. Performance considerations would centre on set design (it is Christmas time), costume and the dynamics between Nora and Torvald. The conversation is about money, and the characters occupy what could be described as parent and child roles in its exchange here. You might choose to emphasize this and direct Nora to play up to this role by suggesting that she makes the running here with Torvald remaining still, keeping the money out of her sight and reach. Or, if you chose to interpret the dynamic of the relationship as one in which Nora has the power (notice that it is she who beckons to Torvald to ‘come here’), then you would need to consider a different approach to directing the movement of the characters.

These two extracts show us how dramatic language is constructed to influence and direct performance through signals and indicators of action. However, not all dramatic language is constituted in this way; some modern drama, for example, deliberately refuses such information, giving us little in the way of signs or directions.

Approaching Plays. Licensed under CC BY SA 4.0 http://www.open.edu/openlearn/history-the-arts/culture/literature-and-creative-writing/literature/approaching-plays/content-section-6.1

Performance Spaces

Dramatic texts intended for performance are, in an important sense, a ‘living’ art form. Plays are conceived with a particular space in mind, and to varying degrees the relationship between the text and its enactment is influenced by the kinds of theatre practices and spaces that have become conventionalized. Some plays lend themselves to particular kinds of performance spaces, such as Brecht’s Mahogonny (1927), which carried over the boxing ring metaphor of the play’s main theme to a literal method of staging: an in-the-round/arena space was specially constructed to function as a boxing ring for a performance of this play. Similarly, Jim Cartwright’s modern play Road (1989) was written to be performed in a promenade performance space.

A history of the variety and development of performance spaces would show the changing social role and function of drama since its recorded origins in ancient Greece almost 3,000 years ago. It would serve to remind us that what we now recognize as the theatre is far removed from the vast open-air Greek amphitheatres capable of seating up to 24,000 people. We tend to regard going to the theatre as a much more rarefied experience than it would originally have been perceived to be, and came to be treated by play-goers in medieval times or in Shakespeare’s time. We wouldn’t usually associate it with a religious event, we certainly wouldn’t expect to stand throughout a performance and would probably find it strange or even unnerving to be expected to participate in the action. We can trace the most significant changes in the development of performance spaces by looking at the shift in the spatial relationship between audience and performers. Figure 1 broadly illustrates the changes in the spatial relationships between what represents the ‘stage’ and what serves as the auditorium.

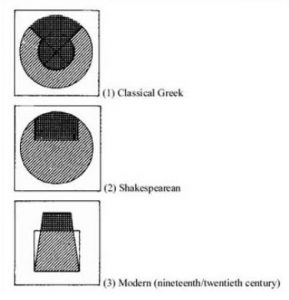

Figure 1 Performance spaces: from the classical to the modern

Look carefully at each, noting that the dark section signifies the performance area and the lighter section the viewing area. What is the main change you observe taking place?

You probably noticed a gradual shift away from a spatial relationship where the audience was grouped around the stage area in an extended semi-circle, to one which had effected almost a complete separation of the stage and the audience. This break started with the introduction of the proscenium arch in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, although the proscenium curtain, used in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, made the more decisive break.

Look at the diagram again. What do you think some of the implications are for performance in each of the performance spaces, as indicated by the spatial relationship between audience and players?

1. The classical model seems more akin to a modern sports stadium than a theatre. The vastness of the audience and semi-circular design of the performance space made the notion of an illusionist set or realist drama impossible. Although the acoustics were generally good, given the scale of even the smallest amphitheatre, I would say that the naturalism we associate with the drama of Ibsen, for example, which often requires intimate conversation to serve as dialogue, would be out of the question here. More appropriate is the stylized, and exaggerated, gesture-like acting which characterized classical Greek drama. This was often accompanied by symbolic costume and masks, and of course, the chorus who commented on the action, addressing the audience directly.

A good example is found in Aristophanes’ 422 BCE comedy, The Wasps:

CHORUS:

Now, ye countless tens of thousands,

Seated on the benches round,

Do not let our pearls of wisdom

Fall unheeded to the ground.

Not that you would be so stupid,

So devoid of common sense –

What it is to have enlightened

People for an audience!

(Baldick, Radice and Jones, 1964, p.75)

2. We probably know more about the conventions of theatre in Shakespeare’s time than we do about our own, so often are they themselves the source of dramatic portrayal, the film, Shakespeare in Love, being a recent example. What this diagram shows us is the proximity between audience and performers, and we can see that the audience still has access to the stage area on three sides. Unlike the amphitheatres of classical Greece, there is close contact between the actors and the spectators, and a further key difference is that these performance areas were housed in purpose-built theatres. Audiences would have been large (the Globe could hold two thousand), and socially disparate. Given the regular interaction between performers and audience, through asides and monologues, it would have been difficult to sustain the notion of dramatic illusion. There was little in the way of set design or décor to consider, thus enabling quick and easy scene changes.

3. The relationship designated by this performance space is the one we most commonly associate with our own experience of the theatre. The intimacy of the darkened space with a brightly lit stage is conducive to the same atmosphere of voyeuristic fascination as we experience in the cinema. We remain detached from the performers, looking into ‘rooms’ whose reality is sustained by scene changes through the use of the proscenium curtain, and the drama assumes a more ‘autonomous’ function. Set design, naturalistic acting and realistic situations create the illusion of reality, thus serving the conventions of the realist drama of, say, Ibsen or Chekhov. As with the other performance spaces, this has its limitations. The playful engagement with the audience by use of asides in Shakespearean and Restoration drama is severely hampered by the distance between audience and performers in this kind of space.

Approaching Plays. Licensed under CC BY SA 4.0 http://www.open.edu/openlearn/history-the-arts/culture/literature-and-creative-writing/literature/approaching-plays/content-section-6.1

Performance and Reception

Our discussion of the performance possibilities for Beckett’s play begins to reveal the author as someone who went to great lengths to articulate a particular artistic vision. The matter of how his plays were received was extremely important to him, and his presence at rehearsals is frequently recounted as an active, if not obtrusive one. Beckett was someone who sought extensive directorial control over the production of his work. Indeed, he made this the subject of one of his plays, in Catastrophe: Tale of an Authoritarian Director (1982) and wrote plays with particular actors in mind; Patrick Magees’s voice, for example, was the one he ‘heard inside his mind’ when writing Krapp’s Last Tape (1958), and Billie Whitelaw’s was the female voice he had listened to when he wrote Not I. For Beckett, the role of the author was one which extended beyond the writing of the text, and one which should be allowed considerable licence in seeing that text realized in performance. Central to his vision were the matters of authenticity and authorial intention. Let’s consider these issues, for a moment, in a different context.

In 1864, a New York production of Hamlet cast a well-known and highly regarded actor, Edwin Booth, in the leading role. Sir John Gielgud also famously played Hamlet in London’s New Theatre production of the play in 1934, as did Jonathan Pryce, at the Royal Court in 1980. Which of these is the real Hamlet, and why?

The short answer is none of them and all of them. I agree that this is not a very satisfactory answer, but it drives home the point that there can be no definitive interpretation of the character and that every performance of Hamlet will say something different both about the play and the context in which it is performed. A longer answer would elaborate these latter two points and explore issues of authenticity and authorial intention, as well as perhaps accounting for changing conceptions of the role of the author and performance.

I want to say something about these issues, but first I’d like to ask you to think about how you answered the question.

I can’t anticipate every possible response to this question, but I’d be surprised if you hadn’t taken into account that the three actors are young, white and male. Photographic stills of the actors would also reveal that each, despite their differences, has a somewhat romantic demeanour, indicative perhaps of the complex range of qualities associated with the role. You might well agree that so far nothing about each of these Hamlets challenges our traditional notion of what the character Hamlet is traditionally supposed to be like. But what if I had asked you to consider a 74-year-old Hamlet, or a female Hamlet? Would you then have been so convinced that this is what Shakespeare intended? I doubt it. You might have felt curious about what such interpretations of the part sought to achieve, or your doubts might have sent you back to the text, to the ‘authorial source’, to find some justification for these performance decisions.

Shakespeare

At this point it is worth remembering that there are many versions of Hamlet, and that historically the editing of the play text reflects a desire to focus on the central character, emphasizing his psychological or emotional condition (Ryan, 2000, p. 163). It is also worth observing that the text, whilst occupying a privileged role in the field of drama today, would not have done so at the time of Hamlet’s early performances. Similarly the author, who today commands a form of reverence among many of his readers and audiences, would not have been regarded with the kind of authority which we now ascribe to writers. Read the following extract and note down what you take to be the main points.

These plays [Shakespeare’s] were made and mediated in the interaction of certain complex material conditions, of which the author was only one. When we deconstruct the Shakespeare myth what we discover is not a universal individual genius creating literary texts that remain a permanently valuable repository of human experience and wisdom; but a collaborative cultural process in which plays were made by writers, theatrical entrepreneurs, architects and craftsmen, actors and audience; a process in which plays were constructed first as performance, and subsequently given the formal permanence of print.

(Holderness, 1988, p. 13)

Holderness emphasizes the collaborative nature of drama and theatre, making the point that plays were the product of a combination of text, production and reception, and not simply sacred pieces of manuscript. He says that theatre was created by the collaborative efforts of playwrights, performers, and a whole host of other craftsmen, as well as through audience response. Indeed, he suggests that far from the text determining the performance, it was more likely to be the case that the performance signalled the direction the writing of the play script would take. Recall, for example, that the staging of Henry V took place before the play text was published.

To illustrate this point further, we can go back beyond Shakespeare to some of the earliest forms of drama where very few of the performers could read or write; in these ritual-based performances a text would not have been necessary, since the components of drama would have been handed down through an oral tradition. Our current valorization of the author and the primacy of the text are then, peculiarly modern concepts, and tend to render the role of the reader, or in the case of performance texts the audience, less significant. This point is made by the critic, Roland Barthes, whose highly influential essay, ‘The death of the author’ (1977), argues for a ‘re-birth’ of the reader as against the primacy of the writer:

A text is made of multiple writings, drawn from many cultures and entering into mutual relations of dialogue, parody, contestation, but there is one place where this multiplicity is focused and that place is the reader, not, as was hitherto said, the author … a text’s unity lies not in its origin but in its destination … Classic criticism has never paid any attention to the reader; for it, the writer is the only person in literature. We are beginning to let ourselves be fooled no longer … we know that to give writing its future, it is necessary to overthrow the myth: the birth of the reader must be at the cost of the death of the author.

(p. 146)

Read in the context of plays and performance, Barthes emphasizes the processes of writing, the multiplicity of perspectives and points of origin of texts, and deconstructs the traditional notion that the author is the point of unity, drawing all the various strands of meaning together. The relevance of Barthes’ argument for considering issues of performance and audience is to be found in the challenge it presents to approaches such as Beckett’s. Barthes argues that our response should not be determined by author or playwright, and that we need to avoid the tendency to think that in ‘getting close’ to the author, we are assured of a more authoritative meaning of the text.

Approaching Plays. Licensed under CC BY SA 4.0 http://www.open.edu/openlearn/history-the-arts/culture/literature-and-creative-writing/literature/approaching-plays/content-section-6.1

Summary

Even if you are not personally familiar with how preparing and planning for a performance works, your ability to read and understand plays can be greatly increased by going to see performances on the stage. For drama, reading and seeing plays are reciprocal activities—when you read a text before seeing the performance, you are guaranteed a fuller experience of the performance itself. When you are familiar with the text, you can notice more about the specific choices that actors, directors, and designers make for a production. When you see a play, the next time you read the text, you will be able to better visual the performance and perhaps you will find your own interpretation of a given moment change based on the production you saw. Seeing a play in performance can often clarify and illuminate moments that are murky in the text. Always try to see a performance or two of the text you are reading, even if it is a video recording of a performance. Your understanding of the text is guaranteed to change based on the choices made in performance.