Week 2 Learning Materials

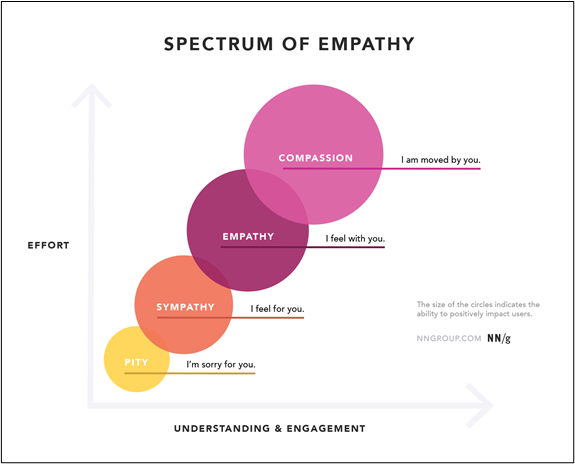

Before diving into our projects by taking this first step, let’s pause to think about the idea of empathy a little more deeply. Like so many intangible concepts investigated in the arts and humanities, empathy lives on a bit of a semantic minefield, especially relative to similar concepts like sympathy and compassion. Here’s what a quick audit of English dictionaries tells us:

| Dictionary.com | Merriam-Webster | Oxford | |

| compassion (noun) | 1: a feeling of deep sympathy and sorrow for another who is stricken by misfortune, accompanied by a strong desire to alleviate the suffering | 1: sympathetic consciousness of others’ distress together with a desire to alleviate it | 1: a strong feeling of sympathy for people or animals who are suffering and a desire to help them |

| empathy (noun) | 1: the psychological identification with or vicarious experiencing of the feelings, thoughts, or attitudes of another | 1: the action of understanding, being aware of, being sensitive to, and vicariously experiencing the feelings, thoughts, and experience of another of either the past or present without having the feelings, thoughts, and experience fully communicated in an objectively explicit manner also : the capacity for this | 1: the ability to understand another person’s feelings, experience, etc. |

| 2: the imaginative ascribing to an object, as a natural object or work of art, feelings or attitudes present in oneself | 2: the imaginative projection of a subjective state into an object so that the object appears to be infused with it | ||

| sympathy (noun) | 1: harmony of or agreement in feeling, as between persons or on the part of one person with respect to another | 1a: an affinity, association, or relationship between persons or things wherein whatever affects one similarly affects the other b: mutual or parallel susceptibility or a condition brought about by it c: unity or harmony in action or effect |

1: the feeling of being sorry for somebody; showing that you understand and care about somebody’s problems |

| 2: the harmony of feeling naturally existing between persons of like tastes or opinion or of congenial dispositions | 2a: inclination to think or feel alike b: feeling of loyalty |

||

| 3: the fact or power of sharing the feelings of another, especially in sorrow or trouble; fellow feeling, compassion, or commiseration | 3a: the act or capacity of entering into or sharing the feelings or interests of another b: the feeling or mental state brought about by such sensitivity have sympathy for the poor |

There are some inconsistencies and contradictions among these, but all three sources seem to agree about the meaning of compassion: it’s the combination of an emotional resonance with another and the desire to proactively mitigate hardships for them. By virtue of the fact that designers proactively intervene in human-related problems (Pinkston 2019), compassion is probably a better way to summarize the designer’s obligation at this step. The designer’s job is twofold: to care about and strive for the best interests of their audience.

Another insight we can take away from our dictionary audit is that sympathy and empathy are both very hard-to-pin-down concepts. Ramsey McNabb’s article below elucidates on this by examining the paradoxical nature of empathy.

The Paradox of Empathy

This short article discusses the challenges of identifying and practicing empathy given the reality that there’s no way to determine how similar one person’s feelings are to another, let alone that they’re identical.

Things get even more challenging when we factor personal experience into the equation: is it possible to empathize with someone whose experiences fundamentally differ from your own? Let’s expand on the scenario suggested by McNabb in the article above by adding a layer of detail: not only are both of Anita’s parents still alive and well, but she has also never personally known anyone who has died. Does not sharing this experience with Hector mean that she also cannot share his emotional response? Not necessarily, but if Anita were to accelerate these feelings of sympathy/empathy into compassionate intervention into Hector’s experience, her lack of experience can certainly make a difference. Let’s look at the following scene from the film Amélie and a critical response to it as an example of the challenge of misaligned feelings and experiences in compassionate action.

Sources

McNabb, R. (n.d.). The Paradox of Empathy. Philosophy Now: a magazine of ideas. https://philosophynow.org/issues/52/The_Paradox_of_Empathy.

Amélie “Helping” a Blind Man

This is a scene from the movie Amélie. We’ll be reading a short critical response to this scene after viewing.

The Fabulous Kindness of Amelie Poulain?

This article written by a blind woman working in academia offers a critical assessment of the scene from Amélie. The contrast between the tone and intent of the scene against the author’s testimony illustrates the pitfalls of acting on misinformed compassion .

There are plenty of real-life examples of ableism in the well-meaning but under-informed attempts of able-bodied people to intervene in challenges faced by the disabled/differently abled, much like this fictional example.

Cochlear implants are a well-documented real-world example of this phenomenon.

As explained by author and medical student Amelia Cooper, “For…critics, deafness is not defined by the lack of ability to hear, but rather, by a distinct cultural identity of which they are proud” (Cooper 2019). How can designers minimize damage and maximize helpfulness when designing for people across any type of cultural divide, big or small? For starters, we might examine the efficacy of the Golden Rule.

Sources

movieclips. (2011, October 1). Amélie (2/12) Movie CLIP – Helping a Blind Man (2001) HD. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Wuntz3KDIAk.

Alternative Text or Captions (if applicable): This clip includes English subtitles.

Thompson, H. (2012, March 8). The Fabulous Kindness of Amelie Poulain? http://hannah-thompson.blogspot.com/2012/03/in-jean-pierre-jeunets-film-le-fabuleux.html.

Why the “Golden Rule” Is Terrible for Everyone

This article expands on our probe into the concept of empathy in its critique of the Golden Rule. Instead, the author points toward the Platinum Rule as a superior framework for would-be do-gooders.

Week 2 Project Deliverables

Bearing in mind all of the above, let’s dive into our first round of making! For this first step in the design thinking process, empathize, you should produce two documents.

| Project Deliverable + File Type to Submit + Naming Convention |

Description |

| Research Deck slide deck exported to pdf week2_researchDeck_[groupname].pdf |

Each group will conduct research to develop a broad, preliminary understanding of the interplay of variables in their problem space (per their design brief), and will create a slide deck to summarize the most important findings. |

| Stakeholder Analysis Miro board exported to jpg week2_stakeholderAnalysis_[groupName].jpg |

Using this article as a reference, use Miro (either from scratch or using template) to create a stakeholder map. Your document must represent the following groups of people:

|

Sources

Dean, S. (2015, March 23). Why the “Golden Rule” Is Terrible for Everyone. Medium. https://stevenmdean.medium.com/why-the-golden-rule-is-terrible-for-everyone-eee38d96985.

How to Do a Stakeholder Analysis

This article from the Lucidchart blog describes what a stakeholder analysis is, how to identify stakeholders, and how to document this research on a map.

Sources

Lucid Content Team. (2021, January 28). How to perform a stakeholder analysis. How to Do a Stakeholder Analysis | Lucidchart Blog. https://www.lucidchart.com/blog/how-to-do-a-stakeholder-analysis.