Section 3: Breaking Down the Mythos: Limitations and Liabilities in and Around Design Thinking

Often associated with Silicon Valley, the phrase design thinking has started showing up in all kinds of work environments: at non-profits, in the offices of elected officials and municipal institutions, in libraries and classrooms, etc. As it’s gained momentum and amassed a diversely populated following, a huge mythos has developed around and convoluted the idea of design thinking that we need to address.

Myth 1: Design thinking is the same thing as thinking like a designer.

Reality: Design thinking and thinking like a designer are different things.

What is the advantage of thinking like a designer? Designers tend to think in a way that we might call non-linear, improvisational, and adaptive. This is especially true compared to lots of professional disciplines in business, the sciences, and the humanities, whose processes are often constrained by disciplinary silos. In this sense what makes design thinking valuable is basically that it can encourage people in these disciplines to “deprogram” from the conventions of whatever industry they studied and/or work in, to make space for novelty, innovativeness, and interdisciplinary collaboration.

So there are advantages to thinking “like a designer,” but what does that mean? It depends on who you ask…

Thinking Like a Designer: the Intuitive Definition

To artists, designers, craftspeople, etc., it simply describes their own way of thinking and general creative approach, or the idea of creative thinking in general. This is the platonic ideal of what’s meant by design thinking. It isn’t a skill, it’s an experience, or a point of view acquired by regularly engaging in creative work.

Design Thinking: the Simulated Definition

To those not in creative disciplines, it refers to the package that’s used to didactically represent the above. It’s a technique, not a frame of reference, and it’s not a substitute for natively inhabiting that kind of headspace. You might think of this like the difference between being a tourist somewhere and being a resident of that place.

These two conceptions are bound together by the understanding that creative thinking can contribute to and enrich disciplines that are not expressly creative; but the intuitive version of this idea and the simulated version are not interchangeable, and the simulated model has a major disadvantage we need to keep in mind.

The “packaging” of design thinking as a set of well-defined steps is what makes it accessible to students and newcomers (like you!), but it’s also misleading and problematic. A package of steps suggests a very linear, assembly-line-style process, which totally undermines the premise that using these tools facilitates non-linear, improvisational, and adaptive thought processes.

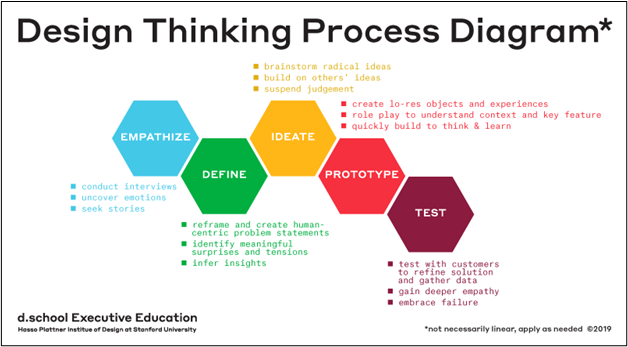

Look at the image below. Do you think most people would interpret this diagram as a sequence of steps, or as a toolkit to draw from and apply in any order as needed? To most it probably reads as the former (with the exception of the fine print in the lower right), but it’s meant to represent the latter.

Why does this all matter? Read on!

Myth 2: Design is harmless and low-stakes work.

Reality: Designers intervene in society and culture and are accountable for the effects of those interventions.

Thinking like a designer is not dogmatic, but packaging this abstract idea as a set of didactic steps suggests an “easy as 1, 2, 3,” mentality, much like a self-help program. And, much like a self-help program, when the package achieves cult-like status its proponents can start behaving in ways that are, well, cult-like: robotic repetition of “doctrine,” tendency to trust more and question less, magic bullet mentalities and savior complexes, etc. etc. There are a lot of advantages to thinking like a designer in non-design work environments and, insofar as design thinking can help facilitate this, it offers some wonderful affordances to groups and individuals wanting to “think outside the box.” It’s unfortunate and ironic, though, that it’s so easy to interpret design thinking as such a boxed-in framework for creative problem-solving, because the application of real-time criticality is the central advantage of design thinking in principle. Without criticality, we’re prone to thoughtless errors, and given the design thinking mandate to be “human-centric,” these errors can be pretty high-stakes.

Decolonizing Design

This paper describes the colonial impact of design thinking in humanitarian design projects.

Myth 3: Users of design thinking should “move fast and break things.”

Reality: This is a socially irresponsible mentality that conflicts with the design thinking mandate to be “human-centric.”

Read the following article by designer Taís Lessa to learn more about this problematic credo.

Sources

Pinkston, Russel. (2019). Decolonizing Design. https://russpinkston.com/wp-content/uploads/RPinkston_DecolonizingDesign-web.pdf

About “moving fast and breaking things” – a designer’s perspective

This article examines the history and problematics of the “move fast and break things” mentality pervasive among tech companies in Silicon Valley (and other SV-sympathetic institutions).

Sources

Lessa, T. (2020, August 22). About “moving fast and breaking things” - a designer’s perspective. Medium. https://uxdesign.cc/about-moving-fast-and-breaking-things-a-designers-perspective-4d3c7c3854a4.

Myth 4: Design thinking is fundamentally human-centric.

Reality: Mainstream applications of design thinking aren’t as human-centric as they could be.

In theory human-centricity should and can be a central tenet of design thinking, but all the conditions described above make this ideal difficult to uphold in mainstream design thinking culture.

Two of the steps in the design thinking process explicitly call for collaboration with users/subjects: empathize and test. Hypothetically, research participants could be engaged during every step of the process, although someone working in the “move fast and break things” paradigm may not have the time or inclination to make ubiquitous user engagement a part of their process. In his introduction to Decolonizing Design, Pinkston observes, “…the commercialization of design practice has often skewed the motivations of the designer…toward one where the designer’s ultimate goal is to satisfy his or her own needs, rather than those of the user” (Pinkston 2019); in other words, while human-centricity is the intent, designer-centricity is often the outcome.

Myth 5: Problems can be conclusively defined and solved.

Reality: “Solutions” or interventions to problems often result in the creation of new problems.

Words like “solving” and “solution” are deeply embedded in the semantics of design thinking. But how much of a solution is something if, in order to address a problem, it cultivates new problems? Author and critic of techno-solutionism Evgeny Morozov explains, “Recasting…complex social situations either as neatly defined problems with definite, computable solutions or as transparent and self-evident processes that can be easily optimized…is likely to have unexpected consequences that could eventually cause more damage than the problems they seek to address” (Morozov 2013).

This course will occasionally generalize engagement with or intervention into problems as “problem-solving,” but when you encounter this kind of language, know that it is either misguided or being used as shorthand to describe a more complicated relationship between people and problems.