28

The Great Depression had devastated the American economy as well as American morale. Unemployment peaked at twenty-five percent in 1932. And as late as 1939, sixty percent of rural households and eighty-two percent of farm families were classified as impoverished. FDR’s New Deal policies worked to pull the nation out of the Depression. Greater government regulation of banks and businesses through programs such as the Glass-Steagall Act and the National Industrial Recovery Act, worked to stabilize the economy. Programs such as the Civilian Conservation Corp and the Works Progress Administration gave direct federal aid to struggling Americans through work programs. While all of these programs did begin the work of pulling the nation out of depression, many historians have argued that it was not until World War II that the United States fully recovered.

Fighting a war abroad required the full scale ramping up of American industry and the American workforce. To encourage businesses to switch to producing goods and materials for war, the government agreed to assume all costs of development and production and guaranteed profits on the sale of these goods. This resulted in corporate profits rising from $6.4 billion in 1940 to $11 billion in 1944, in large part thanks to government contracts.

When the war ended, many feared that the United States would fall back into depression. In order to combat this fear, the federal government took steps to ensure economic opportunity and stability for returning veterans. At the same time, tensions with the communist Soviet Union intensified. The resulting Cold War, as the ongoing tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union came to be called, spurred growth in American industry and technology in an effort to maintain the upper hand militarily and also spurred the growth of consumer production in order to demonstrate the economic and social superiority of American capitalism.

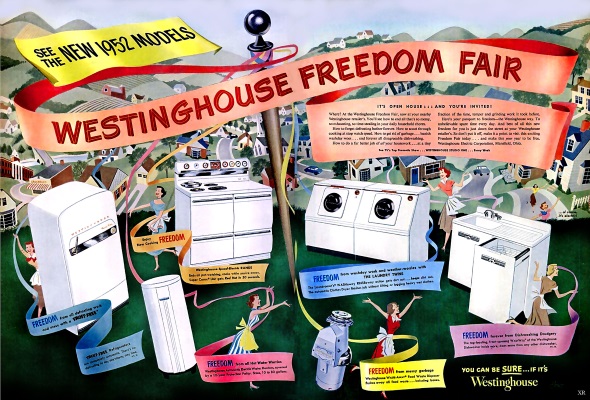

The result of government support of returning veterans and the Cold War struggle was that more Americans entered the middle-class in the decade following the end of World War II. This allowed more American families to take advantage of the new goods and services available. Thus, the 1950s has come to be described as a decade dominated by consumerism.

The Rise of the Middle Class

Suburban America

The federal housing policies of the New Deal and World War II periods helped to fuel the postwar economy and fueled the growth of homeownership and the rise of the suburbs. The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act (popularly known as the G.I. Bill), passed in 1944, offered low-interest home loans, a stipend to attend college, loans to start a business, and unemployment benefits, all of which were geared toward creating economic opportunity for returning veterans. This made homeownership more accessible to Americans and allowed many Americans residential stability and the ability to accrue equity and wealth as property values rose over time.

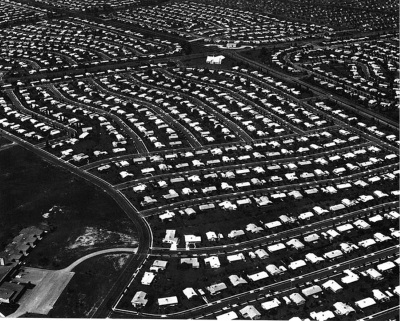

The country’s suburban share of the population rose from 19.5% in 1940 to 30.7% by 1960. Homeownership rates rose from 44% in 1940 to almost 62% in 1960. Between 1950 and 1970, America’s suburban population nearly doubled to 74 million. 83% of all population growth occurred in suburban places.

This suburban lifestyle was aided further by the Federal-Aid Highway Act (1956). This act provided federal aid to a national network of interstate highways to serve the needs of defense and commerce. But in practical application, it provided the highways necessary to move suburbanites between their homes in the suburbs and jobs in the city. Naturally, this led to further the demand for automobiles. The percentage of American families owning cars increased from 54% in 1948 to 74% in 1959. Suburban life and car ownership were the markers of a middle-class life.

The Inequality of Affluence

However, increased funding for highway construction left less money for public transportation, making it impossible for those who could not afford automobiles to live in the suburbs. Beneath the aggregate numbers, racial disparity, sexual discrimination, and economic inequality persevered. While suburbanization and the new consumer economy produced unprecedented wealth and affluence, this economic abundance did not reach all Americans equally. Wealth created by the booming economy filtered through social structures with built-in privileges and prejudices. Just when many middle- and working-class white American families began their journey of upward mobility by moving to the suburbs with the help of government programs such as the Federal Housing Authority (FHA) and the GI Bill, many African Americans and other racial minorities found themselves systematically shut out of these programs and thus the benefits.

A look at the relationship between federal organizations such as the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) and FHA and private banks, lenders, and real estate agents tells the story of the creation of a segregated housing market. HOLC appraisal techniques reflected the existing practices of private realtors, which insisted that mixed-race and minority-dominated neighborhoods were credit risks. In partnership with local lenders and real estate agents, HOLC created Residential Security Maps to identify high and low risk-lending areas. Relying on this information, HOLC assigned every neighborhood a letter grade from A to D and a corresponding color code. The least secure, highest risk neighborhoods for loans received a D grade and the color red. Banks limited loans in such “redlined” areas. Thus, limiting African Americans ability to acquire home loans.

While the HOLC was a fairly short-lived New Deal agency, the influence of its security maps lived on in the FHA and Veteran’s Administration (VA), the latter of which dispensed GI Bill-backed mortgages. Both of these government organizations, which reinforced the standards followed by private lenders, refused to back bank mortgages in “redlined” neighborhoods. On the one hand, FHA- and VA-backed loans allowed millions of Americans to receive mortgages that they otherwise would not have qualified for. But FHA-backed mortgages were not available to all. Racial minorities could not get loans for property improvements in their own neighborhoods—seen as credit risks—and were denied mortgages to purchase property in other areas for fear that their presence would extend the red line into a new community. Levittown, the poster-child of the new suburban America, only allowed whites to purchase homes. Thus, FHA policies and private developers increased home ownership and stability for white Americans while simultaneously creating and enforcing racial segregation.

Television: Homogenizing American Culture

“The American household is on the threshold of a revolution,” the New York Times declared in August 1948. “The reason is television.” In 1947, regular full-scale broadcasting became available to the public. Television was instantly popular. By the end of the 1950s, 90 percent of American families had one and the average viewer was tuning in for almost 5 hours a day.

Television borrowed radio’s organizational structure. The big radio broadcasting companies, NBC, CBS, and ABC, used their technical expertise and capital reserves to conquer the airwaves. They acquired licenses to local stations and eliminated their few independent competitors. The Federal Communication Commission’s (FCC) refusal to issue any new licenses between 1948 and 1955 was a de facto endorsement of the big three’s stranglehold on the market.

The limited number of channels and programs meant that networks selected programs that appealed to the widest possible audience and, more importantly, television’s greatest financiers: advertisers. By the mid-1950s, an hour of primetime programming cost about $150,000 (about $1.5 million in today’s dollars) to produce. This proved too expensive for most commercial sponsors, who began turning to a joint financing model of 30-second spot ads. The commercial’s need to appeal to as many people as possible promoted the production of non-controversial shows aimed at the entire family. Programs such as Father Knows Best and Leave it to Beaver featured light topics, humor, and a guaranteed happy ending the whole family could enjoy.

Television’s broad appeal, however, was about more than money and entertainment. Shows of the 1950s, such as Father Knows Best and I Love Lucy, idealized the nuclear family, “traditional” gender roles, and white, middle-class domesticity. Leave It to Beaver, which became the prototypical example of the 1950s’ television family, depicted its breadwinner-father and homemaker-mother guiding their children through life lessons. Such shows, and Cold War America more broadly, reinforced a popular consensus that such lifestyles were not only beneficial, but the most effective way to safeguard American prosperity against communist threats and social “deviancy.”

The Family & Consumerism

Postwar prosperity and Cold War rhetoric about the importance of stable families facilitated, and in turn was supported by, the ongoing postwar baby boom. From 1946 to 1964, American fertility experienced an unprecedented spike. A century of declining birth rates abruptly reversed. Although popular memory credits the cause of the baby boom to the return of virile soldiers from battle, the real story is more nuanced. After years of economic depression families were now wealthy enough to support larger families and had homes large enough to accommodate them. Women married younger and American culture celebrated the ideal of a large, nuclear family.

Underlying this “reproductive consensus” was the new cult of professionalism that pervaded postwar American culture, including the professionalization of homemaking. Mothers and fathers alike flocked to the experts for their opinions on marriage, sexuality, and, most especially, child-rearing. Books like Dr. Spock’s Baby and Child Care (1946) were diligently studied by women who took their careers as house-wife as just that: a career, complete with all the demands and professional trappings of job development and training. And since most women had multiple children roughly the same age as their neighbors’ children, a cultural obsession with kids flourished throughout the decade. Women bore the brunt of this pressure, chided if they did not give enough of their time to the children—especially if it was because of a career—yet cautioned that spending too much time would lead to “Momism,” producing “sissy” boys who would be incapable of contributing to society and extremely susceptible to the communist threat.

This generation of children born after the Depression experienced a new youth culture which exploded in American during the 1950s. On the one hand, the anxieties of the atomic age hit America’s youth particularly hard. Keenly aware of the discontent bubbling beneath the surface of the Affluent Society, many youth embraced rebellion. The 1955 film Rebel Without a Cause demonstrated the restlessness and emotional incertitude of the postwar generation raised in increasing affluence yet increasingly unsatisfied with their comfortable lives.

Young Americans in the postwar period had more disposable income and enjoyed greater material comfort than their forebears. These factors allowed them to devote more time and money to leisure activities and the consumption of popular culture. Rock and roll, which drew from African American roots in the blues, embraced themes popular among teenagers, such as young love and rebellion against authority. They listened to Little Richard, Buddy Holly, and especially Elvis Presley (whose sexually suggestive hip movements were judged subversive).

The so called rebellious youth of the 1950s, with their love of rock and roll music, had not yet blossomed into the counter cultural musical and social revolution of the coming decade. But they did provide an outlet for young Americans who wanted to break out of the conformity of middle-class suburban life.

Wright, Ben and Joseph Locke, Eds.(2017). The American Yawp. Retrieved from http://www.americanyawp.com/index.html;

And OpenStax, U.S. History. OpenStax CNX. Jul 27, 2017 http://cnx.org/contents/a7ba2fb8-8925-4987-b182-5f4429d48daa@3.84. With adjustments by Margaret Carmack.

Extension: Car commercial of 1950s selling a second car to suburban housewives. Great example of suburban consumer culture.

Throwback (February 24, 2015). Two-Ford Freedom (1956). [Video File]. Retrieved from

Extension: Primary Source document, VP Richard Nixon talking about American standard of living in 1950s. Demonstrates connection between American consumerism and the Cold War struggle.

Bulletin (The Department of State) XLI (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office: August 17, 1959), 227-236. Available online via The Internet Archive (https://archive.org/details/departmentofstat411959unit_0).

Summary

Against the backdrop of the Cold War, Americans dedicated themselves to building a peaceful and prosperous society after the deprivation and instability of the Great Depression and World War II. Dwight D. Eisenhower, the general who led the United States to victory in Europe in 1945, proved to be the perfect president for the new era. Lacking strong conservative positions, he steered a middle path between conservatism and liberalism, and presided over a peacetime decade of economic growth and social conformity.

With the support of the federal government, American businesses expanded, returning veterans were able to find good jobs, get an education, start their own business, and even own their own home. Following World War II, the majority of white Americans were members of the middle class, based on such criteria as education, income, and homeownership. Even most blue-collar families could afford such elements of a middle-class lifestyle as new cars, suburban homes, and regular vacations.

This prosperity ushered in a decade of affluence that shaped American society and began a steady shift in the American economy. 90% of Americans owned a television, on which programming promoted a middle-class suburban life. Out of this developed a culture of conformity that celebrated traditional families and consumption. The drive-in movie theatre, McDonald’s, and other leisure consumer activities geared toward the suburban car-driving family emerged during this period. And the focus on leisure consumption supported in large part by government economic policy would begin to reshape the country’s economy and social structure as the nation began to develop into a post-industrial economy.