22

On February 19, 1942 President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 which ordered the internment of Japanese Americans, no matter whether they were aliens or citizens. With the stated intention of protecting America from espionage, Japanese citizens were forced to give up their homes, their businesses, their land and were taken to internment camps spread throughout the western portion of the United States. Often located in remote or desolate locations, interns ate in common areas and had limited opportunities to engage in work or other cultural activities.

Despite the obvious political and constitutional debate, the Supreme Court upheld the legality of the relocation order in Hirabayashi v. United States and Korematsu v. United States. Anti-Japanese paranoia was at an all-time high. In the event of a Japanese invasion of the mainland United States, fear was pervasive that Japanese posed a security risk. Nisei, the name given to Japanese born in the United States, were treated no differently.

Camp conditions were denigrating. Armed guards stood watch around the clock and some camps barely rose above what would be considered squalid. While young people were expected to attend school, adults were given the option to work for a salary of five dollars per day. Using abandoned horse tracks and military-style barracks, interns were left to find recreational activities to pass the time. While the last camp closed in 1946, it was not until 1976 that a presidential apology was issued and 1988 when congressional reparations were awarded.

President Franklin Roosevelt Signs Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942

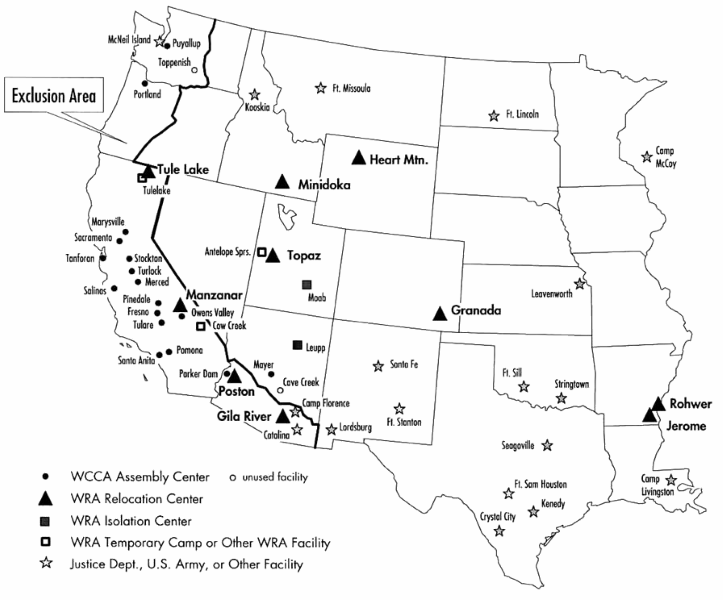

On February 19, 1942, two months after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882-1945) signs Executive Order 9066, setting in motion the expulsion of 110,000 Japanese Americans from the West Coast, first into temporary assembly centers and later to 10 inland prison camps in isolated areas of the country. Two thirds of those imprisoned are U.S. citizens. The government will not permit them return to their communities in Washington, Oregon, California, and Arizona until January 1945.

A Clamor for Expulsion

In the aftermath of Pearl Harbor, as a clamor for their expulsion rose, residents of Japanese American (Nikkei) communities on the West Coast had reason to be uneasy about their security. Japantown residents from Seattle to San Diego clung to the hope that only the immigrant elders might be interned and their U.S.-born descendants spared. However, pressure mounted over the next three months for a mass exclusion of all residents of Japanese ancestry living in the coastal states of Washington, Oregon, and California, regardless of citizenship.

Devastating and humiliating Allied military losses followed the Empire of Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor — at Hong Kong, the Philippines, Wake Island, and Southeast Asia — and a barrage of baseless reports in the press claiming complicity of the Japanese American community with the enemy nation served to raise doubts about the loyalty of Japanese Americans. In January 1942, after assessing the causes of the disaster at Pearl Harbor, Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox (1874-1944) exacerbated these concerns by claiming that a “fifth column” (internal supporters of an external attacker) was at work in Hawaii, thereby implicating Japanese Americans living there. A subsequent ad hoc commission headed by Supreme Court Justice Owen J. Roberts (1875-1955) ultimately laid blame on military incompetence. But it also inaccurately cited fifth-column activity in the islands, thus pointing a false finger of blame specifically at Japanese Americans.

The press kept alive fears of an enemy in the midst by hawking the Roberts Report and spreading unsubstantiated rumors, one of them of downed Japanese pilots at Pearl Harbor found wearing college rings from American universities. This rumor took on local flavors when rings were identified as being from UCLA, Stanford, or the University of Washington depending on where the stories originated.

Thus, as a result of a scapegoating military, citizens with a prejudice against resident Japanese, a nationalistic press, and the ongoing silence of President Roosevelt, the country appeared poised to support action against Nikkei communities. The first formal proposal for a mass incarceration came just 12 days after Pearl Harbor, when 4th Army Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt (1880-1962), head of the Western Defense Command, called for removal and internment of all enemy aliens over the age of 14 living in the coastal regions of the American West. Had these recommendations been approved and implemented, 40,000 Japanese aliens and even more German and Italian nationals would have been forced from their homes. Between then and mid-February 1942, when President Roosevelt finally authorized the military to act, arguments raged in the administration over whether all Japanese, both aliens and U.S. citizens, should be removed from the West Coast.

Those who viewed the presence of Japanese Americans as a threat to the nation’s security prevailed, and on February 19, 1942, the president issued Executive Order 9066, authorizing the Secretary of War and his military commanders to identify military areas from which “any or all persons may be excluded” (“Transcript …”). Although silent on which groups should be excluded or the geographic locations from which they should be excluded, interpretation of the order soon focused specifically on the Nikkei population residing on the West Coast, two thirds of them U.S. citizens by birth. Roosevelt’s action appeared to validate the army’s argument that evacuation was a military necessity because loyal Japanese Americans could not be distinguished from the disloyal.

Exclusion Begins

Six days later, on February 25, navy officials ordered Nikkei residents of Terminal Island, located in Los Angeles Harbor next to a navy shipyard, to vacate their homes. The 500 residents impacted by this order thus became the first Japanese group to be moved out en masse. On March 2, General DeWitt issued the first of four exclusionary proclamations, which divided the states of Washington, Oregon, California, and Arizona into two military areas from which Japanese would ultimately be excluded. Military Area 1 included roughly the western halves of the states of Washington, Oregon, and California and the southern third of Arizona. Later, on March 30, DeWitt expanded the exclusion zones to include the remainder of California, located in Military Area 2.

Civilian Exclusion Order No. 1, which DeWitt issued on March 24, ordered removal of the Japanese American residents of Bainbridge Island, located on the west shore of Puget Sound directly across from Seattle. Because no facility in the Pacific Northwest was yet ready to receive them, the Bainbridge Island group was sent by train to the Owens Valley Reception Center (subsequently renamed the Manzanar War Relocation Center) in eastern California, becoming the first Japanese placed in an incarceration camp under Executive Order 9066. (The Japanese residents removed from Terminal Island in February also ended up at the Manzanar camp, but arrived there after the Bainbridge Islanders did).

Within a month, a mass exodus started as the army began posting additional civilian exclusion orders in all areas on the West Coast that had a Japanese presence. With assistance from the Census Bureau, the army divided the two exclusion zones into 108 geographic areas, each averaging approximately 1,000 Japanese residents (ranging from 243 to 3,867). Civilian exclusion orders for each of those areas were drawn up and posted in shop windows, on telephone poles, and in other public places, providing details of when the area was to be emptied and where people were to report. The last of these orders was fully implemented by the end of August 1942.

Overall, more than 90,000 U.S. citizens and their alien elders were herded into existing public facilities that the government euphemistically called “assembly centers.” Twenty thousand others were taken directly from their homes to long-term “relocation centers” once those were ready for occupancy. The men, women, and children who went to the assembly centers were later sent to the “relocation centers” (more accurately prison or concentration camps), 10 in all, located in sparsely populated regions of the arid west and swampy areas of Arkansas.

This incarceration proceeded without due process of law as required by the U.S. Constitution. In fact, no camp inmate was accused of any crime or charged or convicted of any act of espionage or sabotage.

President Roosevelt Signs Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 2942 Retrieved August 29, 2017 from http://www.historylink.org/File/310

“Never Again” by Ken Burns

Watch this mini-documentary highlighting the stories of Japanese Americans during WWII here.

Manzanar Committee: “Never Again” by Ken Burns Retrieved August 29, 2017 from https://blog.manzanarcommittee.org/2009/07/18/manzanar-never-again-released-video-by-ken-burns/

Manzanar Committee Blog is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 at https://blog.manzanarcommittee.org/2009/07/18/manzanar-never-again-released-video-by-ken-burns/

Summary

Executive Order 9066 incarcerated over 120,000 Americans of Japanese descent. The Order did not include the Japanese living in Hawaii, as that would exclude nearly forty percent of the population from the workforce. White business owners protested the initial inclusion and won exception by the President. And while thousands of German and Italian aliens were also rounded up and interned, most remained free to go about their lives as they had prior to the war.

In the process of relocation, Japanese families lost everything. In addition to their homes, land, and businesses, many Japanese Americans also lost their possessions to include their clothing. There were ten camps located in seven states. Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, and Idaho each had one, while Arizona, Arkansas and California each had two camps. To pass the time they organized baseball leagues and carved out tracks for exercise. Their children went to school and groups organized entertainment for the masses. But the conditions were uncomfortable, if not poor. Built on race tracks and fairground, the temperature was often too hot or too cold. The air was clouded in dust as the locations were remote and rural.

By mid-1944 the government began to release the interns. However, it took until January 1945 for all interns to be released. While some returned home, thousands never went back to their previous residence and instead relocated to start anew. Those who did return often found their homes in ruin or, worse, that in their absence strangers began to occupy the residents and had to be evicted.

By 1948, the government began to issue paltry reparations. However, it took forty years for Congress to approve an official apology and a lump sum additional payment to each surviving internee.