14

By the middle of the 20th century, the New Deal had become a foundational component of American government. Even though many conservatives criticized the New Deal and the development of the modern “welfare state,” many Americans had become so accustomed to New Deal programs that they had simply become accepted features of American society. In the 1950s and early 1960s, however, several dramatic shifts in American politics gave rise to a “new conservatism,” which began to erode the New Deal consensus that had emerged in during the 1930s and 1940s.

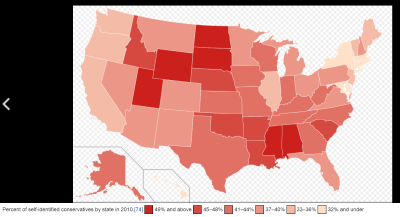

Three major factors contributed to the rise of conservatism and the development of the modern Republican Party. First, during the 1940s and 1950s, the Democratic Party splintered over civil rights and race. Democratic strongholds in the South, which had consistently voted Democratic since the Civil War, began to increasingly vote Republican in the 1950s and early 1960s. Second, Christian conservatives began to emerge as a powerful conservative voting bloc in American politics in the 1960s and 1970s, and they consistently turned out to the polls in large numbers in response to their perception that liberals, and the government in general, was attacking religious values by advocating specific policies that they found immoral. Finally, a new strain of neo-conservative coalesced around critiques of the welfare state, Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society, and America’s role in world affairs and Vietnam. Asserting that the “welfare state” made Americans dependent on the government and created cyclical poverty, conservative ideas began to gain traction. When Ronald Reagan was elected President in 1980, it signaled that conservative ideas and values, which seemed to have lost the war of ideas against the New Deal by 1960, had made a comeback.

The New Conservatism

I. Introduction

Speaking to Detroit autoworkers in October of 1980, Republican presidential candidate Ronald Reagan described what he saw as the American Dream under Democratic President Jimmy Carter. The family garage may have still held two cars, cracked Reagan, but they were “both Japanese and they’re out of gas.”1 The charismatic former governor of California suggested that a once-proud nation was running on empty. But Reagan held out hope for redemption. Stressing the theme of “national decline,” he nevertheless promised to make the United States once again a glorious “city upon a hill.”2 In November, Reagan’s vision triumphed.

Reagan rode the wave of a powerful political movement often referred to as the “New Right” to contrast the more moderate brand of conservatism popular after World War II. By the 1980s the New Right had evolved into the most influential wing of the Republican Party and could claim significant credit for its electoral successes. Building upon the gradual unraveling of the New Deal political order in the 1960s and 1970s,((See Chapter 28, “The Unraveling.”)) the conservative movement not only enjoyed the guidance of skilled politicians like Reagan but drew tremendous energy from a broad range of grassroots activists. Countless ordinary citizens–newly mobilized Christian conservatives, in particular–helped the Republican Party steer the country onto a rightward course. As enduring conflicts over race, economic policy, sexual politics, and foreign affairs fatally fractured the liberal consensus that had dominated American politics since the presidency of Franklin Roosevelt, the New Right attracted support from “Reagan Democrats,” blue-collar voters who had lost faith in the old liberal creed.

The rise of the right affected Americans’ everyday lives in numerous ways. The Reagan administration’s embrace of free markets dispensed with the principles of active income redistribution and social welfare spending that had animated the New Deal and Great Society in the 1930s and 1960s. And as American liberals increasingly embraced a “rights” framework directed toward African Americans, Latinos, women, lesbians and gays, and other marginalized groups, conservative policymakers targeted the regulatory and legal landscape of the United States. Critics complained that Reagan’s policies served the interests of corporations and wealthy individuals and pointed to the sudden widening of economic inequality, but the New Right harnessed popular distrust of regulation, taxes, and “bureaucrats” and conservative activists celebrated the end of hyperinflation and substantial growth in the gross domestic product.

In many ways, however, the rise of the right promised more than it delivered. Battered but intact, the social welfare programs of the New Deal and Great Society (for example, Social Security, Medicaid, and Aid to Families With Dependent Children) survived the 1980s. Despite Republican vows of fiscal discipline, both the federal government and the national debt ballooned. At the end of the decade, conservative Christians viewed popular culture as more vulgar and hostile to their values than ever before. And in the near term, the New Right registered only partial victories on a range of public policies and cultural issues. Yet, from a long-term perspective, conservatives achieved a subtler and more enduring transformation of American politics and society. In the words of one historian, the conservative movement successfully “changed the terms of debate and placed its opponents on the defensive.”3 Liberals and their programs and their policies did not disappear, but they increasingly fought battles on terrain chosen by the New Right.

II. Conservative Ascendance

The “Reagan Revolution” marked the culmination of a long process of political mobilization on the American right. In the first two decades after World War II the New Deal seemed firmly embedded in American electoral politics and public policy. Even two-term Republican President Dwight D. Eisenhower declined to roll back the welfare state. To be sure, William F. Buckley tapped into a deep vein of elite conservatism in 1955 by announcing in the first issue of National Review that his magazine “stands athwart history yelling Stop.”4 Senator Joseph McCarthy and John Birch Society founder Robert Welch stirred anti-communist fervor. But in general, the far right lacked organizational cohesion. Following Lyndon Johnson’s resounding defeat of Republican standard-bearer Barry Goldwater in the 1964 presidential election, many observers declared American conservatism finished. New York Times columnist James Reston wrote that Goldwater had “wrecked his party for a long time to come.”5

Despite these dire predictions, conservatism not only persisted, it prospered. Its growing appeal had several causes. The expansive social and economic agenda of Johnson’s Great Society reminded anti-communists of Soviet-style central planning and enflamed fiscal conservatives worried about deficits. Race also drove the creation of the New Right. The civil rights movement, along with the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act, upended the racial hierarchy of the Jim Crow South. All of these occurred under Democratic leadership, pushing white southerners toward the Republican Party. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Black Power, affirmative action, and court-ordered busing of children between schools to achieve racial balance brought “white backlash” in the North, often in cities previously known for political liberalism. To many white Americans, the urban rebellions, antiwar protests, and student uprisings of the late 1960s signaled social chaos. At the same time, slowing wage growth, rising prices, and growing tax burdens brought economic vulnerability to many working- and middle-class citizens who long formed the core of the New Deal coalition. Liberalism no longer seemed to offer the great mass of white Americans a roadmap to prosperity, so they searched for new political solutions.

Former Alabama governor and conservative Democrat George Wallace masterfully exploited the racial, cultural, and economic resentments of working-class whites during his presidential runs in 1968 and 1972. Wallace’s record as a staunch segregationist made him a hero in the Deep South, where he won five states as a third-party candidate in the 1968 general election. Wallace’s populist message also resonated with blue-collar voters in the industrial North who felt left behind by the rights revolution. On the campaign stump, the fiery candidate lambasted hippies, anti-war protestors, and government bureaucrats. He assailed female welfare recipients for “breeding children as a cash crop” and ridiculed “over-educated, ivory-tower” intellectuals who “don’t know how to park a bicycle straight.”6 Yet, Wallace also advanced progressive proposals for federal job training programs, a minimum wage hike, and legal protections for collective bargaining. Running as a Democrat in 1972 (and with anti-busing rhetoric as a new arrow in his quiver), Wallace captured the Michigan primary and polled second in the industrial heartland of Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and Indiana. In May 1972 an assassin’s bullet left Wallace paralyzed and ended his campaign. Nevertheless, his amalgamation of older, New Deal-style proposals and conservative populism represented the rapid re-ordering of party loyalties in the late ’60s and early ’70s. Richard Nixon similarly harnessed the New Right’s sense of grievance through his rhetoric about “law and order” and the “silent majority.”7 But Nixon and his Republican successor, Gerald Ford, continued to accommodate the politics of the New Deal order. The New Right remained restive.

Christian conservatives also felt themselves under siege from liberalism. In the early 1960s, Supreme Court decisions prohibiting teacher-led prayer (Engel v. Vitale) and Bible reading in public schools (Abington v. Schempp) led some on the right to conclude that a liberal judicial system threatened Christian values. In the following years, the counterculture’s celebration of sex and drugs, along with relaxed obscenity and pornography laws, intensified the conviction that “permissive” liberalism encouraged immorality in private life. Evangelical Protestants—Christians who professed a personal relationship with Jesus Christ, upheld the Bible as an infallible source of truth, and felt a duty to convert, or evangelize, nonbelievers—comprised the core of the so-called “religious right.”

With increasing assertiveness in the 1960s and 1970s, Christian conservatives mobilized to protect the “traditional” family. Women comprised a striking number of the religious right’s foot soldiers. In 1968 and 1969 a group of newly politicized mothers in Anaheim, California led a sustained protest against sex education in public schools.8 Catholic activist Phyllis Schlafly marshaled opposition to the Equal Rights Amendment, while evangelical pop singer Anita Bryant drew national headlines for her successful fight to repeal Miami’s gay rights ordinance in 1977. In 1979, Beverly LaHaye (whose husband Tim–an evangelical pastor in San Diego–would later co-author the wildly popular Left Behind Christian book series) founded Concerned Women for America, which linked small groups of local activists opposed to the ERA, abortion, homosexuality, and no-fault divorce.

Activists like Schlafly and LaHaye valorized motherhood as women’s highest calling. Abortion therefore struck at the core of their female identity. More than perhaps any other issue, abortion drew different segments of the religious right—Catholics and Protestants, women and men—together. The Supreme Court’s 1973 Roe v. Wade ruling outraged many devout Catholics and evangelicals (who had been less universally opposed to the procedure than their Catholic counterparts). Christian author Francis Schaeffer cultivated evangelical opposition to abortion through the 1979 documentary film Whatever Happened to the Human Race? arguing that the “fate of the unborn is the fate of the human race.”9 With the procedure framed in stark, existential terms, many evangelicals felt compelled to combat the procedure through political action.

Grassroots passion drove anti-abortion activism, but a set of religious and secular institutions turned the various strands of the New Right into a sophisticated movement. In 1979 Jerry Falwell—a Baptist minister and religious broadcaster from Lynchburg, Virginia—founded the Moral Majority, an explicitly political organization dedicated to advancing a “pro-life, pro-family, pro-morality, and pro-American” agenda. The Moral Majority skillfully wove together social and economic appeals to make itself a force in Republican politics. Secular, business-oriented institutions also joined the attack on liberalism, fueled by stagflation and by the federal government’s creation of new regulatory agencies like the Environmental Protection Agency and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Conservative business leaders bankrolled new “think tanks” like the Heritage Foundation and the Cato Institute. These organizations provided grassroots activists with ready-made policy prescriptions. Other business leaders took a more direct approach by hiring Washington lobbyists and creating Political Action Committees (PACs) to press their agendas in the halls of Congress and federal agencies. Between 1976 and 1980 the number of corporate PACS rose from under 300 to over 1200.

Grassroots activists and business leaders received unlikely support from a circle of “neoconservatives”—disillusioned intellectuals who had rejected liberalism and the Left and become Republicans. Irving Kristol, a former Marxist who went on to champion free-market capitalism as a Wall Street Journal columnist, defined a neoconservative as a “liberal who has been mugged by reality.”10 Neoconservative journals like Commentary and Public Interest argued that the Great Society had proven counterproductive, perpetuating the poverty and racial segregation that it aimed to cure. By the middle of the 1970s, neoconservatives felt mugged by foreign affairs as well. As ardent Cold Warriors, they argued that Nixon’s policy of détente left the United States vulnerable to the Soviet Union.

In sum, several streams of conservative political mobilization converged in the late 1970s. Each wing of the burgeoning New Right—disaffected Northern blue-collar workers, white Southerners, evangelicals and devout Catholics, business leaders, disillusioned intellectuals, and Cold War hawks—turned to the Republican Party as the most effective vehicle for their political counter-assault on liberalism and the New Deal political order. After years of mobilization, the domestic and foreign policy catastrophes of the Carter administration provided the head winds that brought the conservative movement to shore.

Extension: Reagan, R (1981). First inaugural address of Ronald Reagan [Transcript]. Retrieved from http://www.americanyawp.com/reader/29-the-triumph-of-the-right/first-inaugural-address-of-ronald-reagan-1981/

Extension: Ronald Reagan – Inaugural Address [Video file]. (1981). Retrieved from http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/youtubeclip.php?clipid=43130

Richard Anderson et al (2016). The Triumph of the Right. In Richard Anderson and William J. Schultz (Ed.), The American Yawp. Retrieved from http://www.americanyawp.com/text/29-the-triumph-of-the-right/

- Ronald Reagan quoted in Steve Neal, “Reagan Assails Carter On Auto layoffs,” Chicago Tribune, October 20, 1980, 5. [↩]

- Ronald Reagan quoted in James T. Patterson, Restless Giant: The United States From Watergate to Bush v. Gore (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 152. [↩]

- Robert Self, All in the Family: The Realignment of American Democracy Since the 1960s (New York: Hill and Wang, 2012), 369. [↩]

- William F. Buckley, Jr., “Our Mission Statement,” National Review, November 19, 1955. http://www.nationalreview.com/article/223549/our-mission-statement-william-f-buckley-jr. Accessed on June 29, 2015. [↩]

- James Reston, “What Goldwater Lost: Voters Rejected His Candidacy, Conservative Cause and the G.O.P.,” New York Times, November 4, 1964, 23. [↩]

- George Wallace quoted in William Chafe, The Unfinished Journey: America Since World War II (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 377. [↩]

- James Patterson, Grand Expectations: The United States, 1945-1974 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 735-736. [↩]

- Lisa McGirr, Suburban Warriors: The Origins of the New American Right ( Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001), 227-231. [↩]

- Francis Schaeffer quoted in Whatever Happened to the Human Race? (Episode I), Film, directed by Franky Schaeffer, (1979, USA, Franky Schaeffer V Productions). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UQAyIwi5l6E. Accessed June 30, 2015. [↩]

- Walter Goodman, “Irving Kristol: Patron Saint of the New Right,” New York Times Magazine, December 6, 1981. http://www.nytimes.com/1981/12/06/magazine/irving-kristol-patron-saint-of-the-new-right.html. Accessed June 24, 2015. [↩]

The New Conservatism

Ronald Reagan entered the White House in 1981 with strongly conservative values but experience in moderate politics. He appealed to moderates and conservatives anxious about social change and the seeming loss of American power and influence on the world stage. Leading the so-called Reagan Revolution, he appealed to voters with the promise that the principles of conservatism could halt and revert the social and economic changes of the last generation. Reagan won the White House by citing big government and attempts at social reform as the problem, not the solution. He was able to capture the political capital of an unsettled national mood and, in the process, helped set an agenda and policies that would affect his successors and the political landscape of the nation.

REAGAN’S EARLY CAREER

Although many of his movie roles and the persona he created for himself seemed to represent traditional values, Reagan’s rise to the presidency was an unusual transition from pop cultural significance to political success. Born and raised in the Midwest, he moved to California in 1937 to become a Hollywood actor. He also became a reserve officer in the U.S. Army that same year, but when the country entered World War II, he was excluded from active duty overseas because of poor eyesight and spent the war in the army’s First Motion Picture Unit. After the war, he resumed his film career; rose to leadership in the Screen Actors Guild, a Hollywood union; and became a spokesman for General Electric and the host of a television series that the company sponsored. As a young man, he identified politically as a liberal Democrat, but his distaste for communism, along with the influence of the social conservative values of his second wife, actress Nancy Davis, edged him closer to conservative Republicanism (Figure). By 1962, he had formally switched political parties, and in 1964, he actively campaigned for the Republican presidential nominee Barry Goldwater.

Reagan launched his own political career in 1966 when he successfully ran for governor of California. His opponent was the incumbent Pat Brown, a liberal Democrat who had already served two terms. Reagan, quite undeservedly, blamed Brown for race riots in California and student protests at the University of California at Berkeley. He criticized the Democratic incumbent’s increases in taxes and state government, and denounced “big government” and the inequities of taxation in favor of free enterprise. As governor, however, he quickly learned that federal and state laws prohibited the elimination of certain programs and that many programs benefited his constituents. He ended up approving the largest budget in the state’s history and approved tax increases on a number of occasions. The contrast between Reagan’s rhetoric and practice made up his political skill: capturing the public mood and catering to it, but compromising when necessary.

REPUBLICANS BACK IN THE WHITE HOUSE

After two unsuccessful Republican primary bids in 1968 and 1976, Reagan won the presidency in 1980. His victory was the result of a combination of dissatisfaction with the presidential leadership of Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter in the 1970s and the growth of the New Right. This group of conservative Americans included many very wealthy financial supporters and emerged in the wake of the social reforms and cultural changes of the 1960s and 1970s. Many were evangelical Christians, like those who joined Jerry Falwell’s Moral Majority, and opposed the legalization of abortion, the feminist movement, and sex education in public schools. Reagan also attracted people, often dubbed neoconservatives, who would not previously have voted for the same candidate as conservative Protestants did. Many were middle- and working-class people who resented the growth of federal and state governments, especially benefit programs, and the subsequent increase in taxes during the late 1960s and 1970s. They favored the tax revolts that swept the nation in the late 1970s under the leadership of predominantly older, white, middle-class Americans, which had succeeded in imposing radical reductions in local property and state income taxes.

Voter turnout reflected this new conservative swing, which not only swept Reagan into the White House but created a Republican majority in the Senate. Only 52 percent of eligible voters went to the polls in 1980, the lowest turnout for a presidential election since 1948. Those who did cast a ballot were older, whiter, and wealthier than those who did not vote (Figure). Strong support among white voters, those over forty-five years of age, and those with incomes over $50,000 proved crucial for Reagan’s victory.

REAGANOMICS

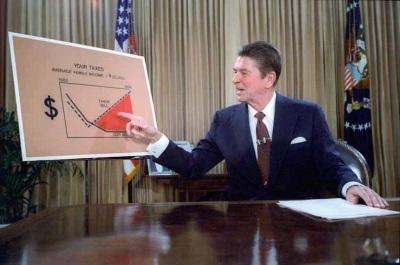

Reagan’s primary goal upon taking office was to stimulate the sagging economy while simultaneously cutting both government programs and taxes. His economic policies, called Reaganomics by the press, were based on a theory called supply-side economics, about which many economists were skeptical. Influenced by economist Arthur Laffer of the University of Southern California, Reagan cut income taxes for those at the top of the economic ladder, which was supposed to motivate the rich to invest in businesses, factories, and the stock market in anticipation of high returns. According to Laffer’s argument, this would eventually translate into more jobs further down the socioeconomic ladder. Economic growth would also increase the total tax revenue—even at a lower tax rate. In other words, proponents of “trickle-down economics” promised to cut taxes and balance the budget at the same time. Reaganomics also included the deregulation of industry and higher interest rates to control inflation, but these initiatives preceded Reagan and were conceived in the Carter administration.

Many politicians, including Republicans, were wary of Reagan’s economic program; even his eventual vice president, George H. W. Bush, had referred to it as “voodoo economics” when competing with him for the Republican presidential nomination. When Reagan proposed a 30 percent cut in taxes to be phased in over his first term in office, Congress balked. Opponents argued that the tax cuts would benefit the rich and not the poor, who needed help the most. In response, Reagan presented his plan directly to the people

Reagan was an articulate spokesman for his political perspectives and was able to garner support for his policies. Often called “The Great Communicator,” he was noted for his ability, honed through years as an actor and spokesperson, to convey a mixture of folksy wisdom, empathy, and concern while taking humorous digs at his opponents. Indeed, listening to Reagan speak often felt like hearing a favorite uncle recall stories about the “good old days” before big government, expensive social programs, and greedy politicians destroyed the country. Americans found this rhetorical style extremely compelling. Public support for the plan, combined with a surge in the president’s popularity after he survived an assassination attempt in March 1981, swayed Congress, including many Democrats. On July 29, 1981, Congress passed the Economic Recovery Tax Act, which phased in a 25 percent overall reduction in taxes over a period of three years.

RICHARD V. ALLEN ON THE ASSASSINATION ATTEMPT ON RONALD REAGAN

On March 30, 1981, just months into the Reagan presidency, John Hinckley, Jr. attempted to assassinate the president as he left a speaking engagement at the Washington Hilton Hotel. Hinckley wounded Reagan and three others in the attempt. Here, National Security Adviser Richard V. Allen recalls what happened the day President Reagan was shot:

By 2:52 PM I arrived at the White House and went to [Chief of Staff James] Baker’s office . . . and we placed a call to Vice President George H. W. Bush. . . .

[W]e sent a message with the few facts we knew: the bullets had been fired and press secretary Jim Brady had been hit, as had a Secret Service agent and a DC policeman. At first, the President was thought to be unscathed.

Jerry Parr, the Secret Service Detail Chief, shoved the President into the limousine, codenamed “Stagecoach,” and slammed the doors shut. The driver sped off. Headed back to the safety of the White House, Parr noticed that the red blood at the President’s mouth was frothy, indicating an internal injury, and suddenly switched the route to the hospital. . . . Parr saved the President’s life. He had lost a serious quantity of blood internally and reached [the emergency room] just in time. . . .

Though the President never lost his sense of humor throughout, and had actually walked into the hospital under his own power before his knees buckled, his condition became grave.

Why do you think Allen mentions the president’s sense of humor and his ability to walk into the hospital on his own? Why might the assassination attempt have helped Reagan achieve some of his political goals, such as getting his tax cuts through Congress?

Reagan was successful at cutting taxes, but he failed to reduce government spending. Although he had long warned about the dangers of big government, he created a new cabinet-level agency, the Department of Veterans Affairs, and the number of federal employees increased during his time in office. He allocated a smaller share of the federal budget to antipoverty programs like Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), food stamps, rent subsidies, job training programs, and Medicaid, but Social Security and Medicare entitlements, from which his supporters benefited, were left largely untouched except for an increase in payroll taxes to pay for them. Indeed, in 1983, Reagan agreed to a compromise with the Democrats in Congress on a $165 billion injection of funds to save Social Security, which included this payroll tax increase.

But Reagan seemed less flexible when it came to deregulating industry and weakening the power of labor unions. Banks and savings and loan associations were deregulated. Pollution control was enforced less strictly by the Environmental Protection Agency, and restrictions on logging and drilling for oil on public lands were relaxed. Believing the free market was self-regulating, the Reagan administration had little use for labor unions, and in 1981, the president fired twelve thousand federal air traffic controllers who had gone on strike to secure better working conditions (which would also have improved the public’s safety). His action effectively destroyed the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO) and ushered in a new era of labor relations in which, following his example, employers simply replaced striking workers. The weakening of unions contributed to the leveling off of real wages for the average American family during the 1980s.

Reagan’s economic policymakers succeeded in breaking the cycle of stagflation that had been plaguing the nation, but at significant cost. In its effort to curb high inflation with dramatically increased interest rates, the Federal Reserve also triggered a deep recession. Inflation did drop, but borrowing became expensive and consumers spent less. In Reagan’s first years in office, bankruptcies increased and unemployment reached about 10 percent, its highest level since the Great Depression. Homelessness became a significant problem in cities, a fact the president made light of by suggesting that the press exaggerated the problem and that many homeless people chose to live on the streets. Economic growth resumed in 1983 and gross domestic product grew at an average of 4.5 percent during the rest of his presidency. By the end of Reagan’s second term in office, unemployment had dropped to about 5.3 percent, but the nation was nearly $3 trillion in debt. An increase in defense spending coupled with $3.6 billion in tax relief for the 162,000 American families with incomes of $200,000 or more made a balanced budget, one of the president’s campaign promises in 1980, impossible to achieve.

The Reagan years were a complicated era of social, economic, and political change, with many trends operating simultaneously and sometimes at cross-purposes. While many suffered, others prospered. The 1970s had been the era of the hippie, and Newsweekmagazine declared 1984 to be the “year of the Yuppie.” Yuppies, whose name derived from “(y)oung, (u)rban (p)rofessionals,” were akin to hippies in being young people whose interests, values, and lifestyle influenced American culture, economy, and politics, just as the hippies’ credo had done in the late 1960s and 1970s. Unlike hippies, however, yuppies were materialistic and obsessed with image, comfort, and economic prosperity. Although liberal on some social issues, economically they were conservative. Ironically, some yuppies were former hippies or yippies, like Jerry Rubin, who gave up his crusade against “the establishment” to become a businessman.

Section Summary

After decades of liberalism and social reform, Ronald Reagan changed the face of American politics by riding a groundswell of conservatism into the White House. Reagan’s superior rhetorical skills enabled him to gain widespread support for his plans for the nation. Implementing a series of economic policies dubbed “Reaganomics,” the president sought to stimulate the economy while shrinking the size of the federal government and providing relief for the nation’s wealthiest taxpayers. During his two terms in office, he cut spending on social programs, while increasing spending on defense. While Reagan was able to break the cycle of stagflation, his policies also triggered a recession, plunged the nation into a brief period of significant unemployment, and made a balanced budget impossible. In the end, Reagan’s policies diminished many Americans’ quality of life while enabling more affluent Americans—the “Yuppies” of the 1980s—to prosper.

The Reagan Revolution. (n.d.). In OpenStax CNX. Retrieved September 5, 2017, from https://cnx.org/contents/p7ovuIkl@3.84:5voT8wBl@3/The-Reagan-Revolution

Summary

In his first inaugural address in 1981, Ronald Reagan declared, “government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem.” This philosophy flew directly in the face of decades of Democratic policies, which held that the government could cure social ills, eliminate racial inequality, and reduce poverty. As Reagan revealed in his inaugural address, he believed that this approach to government was inherently flawed.

Once conservatives like Reagan actually had the ability to shape American policy, they put their beliefs into action. Since 1981, conservative ideology has held enormous sway over American politics, and conservative attacks on the welfare state and liberal tax policies, as well as numerous “culture wars” between the ideological left and right have become the new normal in America. When Fox News launched on October 7, 1996, the “culture wars” became a dominant theme on cable television, and according to public opinion polls partisanship and the ideological divide between Democrats and Republicans has only become more extreme. Why do you think conservative ideas and values gained so much traction in the United States since the 1950s? And why do you think so many Americans in 1981 agreed with Ronald Reagan’s contention that “government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem”?