11

After the stock market crashed in 1929, the Republican administration of President Herbert Hoover took a laissez-faire approach to the recession. Hoover supported an ideology known as “Associationalism,” which held that voluntary organizations could address Americans’ needs in times of crisis. Hoover explicitly did not support the notion that the government should directly intervene in the recession, believing that direct government intervention or aid would discourage Americans’ independence and work ethic. These ideas were hardly new, and can be traced back to widely held assumptions about the role of the federal government in public life dating back to the 19th century. However, as the Great Depression deepened its hold on the United States economy, many Americans began to view Hoover and the Republican Party’s approach to the economy as cold-hearted and ineffective. Many voluntary organizations had initially attempted to provide assistance to Americans who had been hit by the depression, but throughout the country voluntary associations quickly realized that they simply did not have the resources to address the scope of the depression adequately. As a result, by the early 1930s, many Americans were questioning the Hoover administration’s approach to the economy and the notion that Americans only needed to work harder to support themselves and their families. Although many Americans initially blamed themselves for their economic status in the wake of the Great Depression, over time it became increasingly evident that most Americans had little control over the economic forces that had driven them into poverty.

In 1932, Franklin Delano Roosevelt ran as the Democratic candidate for president on a platform that emphasized a new approach to the Great Depression and promised the nation “a new deal for the American people.” As a result of his campaign and Hoover’s unpopularity, Roosevelt won in a landslide, and quickly set out to utilize the government to respond to the Great Depression. In the first 100 days of his presidency, FDR declared a “bank holiday” and attempted to stabilize American financial institutions, instituted weekly “fireside chats” which were broadcast on the radio, and implemented the first wave of New Deal legislation, which largely focused on providing Americans who had already lived through three years of depression with economic relief. FDR’s presidency and the New Deal legislation he oversaw represented one of the most significant transformations in how the federal government and the Executive Branch operated in the 20th century. A new, much larger, and much more interventionist American government had risen from the ashes of the Great Depression.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the “First” New Deal

The early years of the Depression were catastrophic. The crisis, far from relenting, deepened each year. Unemployment peaked at 25% in 1932. With no end in sight, and with private firms crippled and charities overwhelmed by the crisis, Americans looked to their government as the last barrier against starvation, hopelessness, and perpetual poverty.

Few presidential elections in modern American history have been more consequential than that of 1932. The United States was struggling through the third year of the Depression and exasperated voters overthrew Hoover in a landslide to elect the Democratic governor of New York, Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Roosevelt came from a privileged background in New York’s Hudson River Valley (his distant cousin, Theodore Roosevelt, became president while Franklin was at Harvard). Franklin Roosevelt embarked upon a slow but steady ascent through state and national politics. In 1913, he was appointed Assistant Secretary of the Navy, a position he held during the defense emergency of World War I. In the course of his rise, in the summer of 1921, Roosevelt suffered a sudden bout of lower-body pain and paralysis. He was diagnosed with polio. The disease left him a paraplegic, but, encouraged and assisted by his wife, Eleanor, Roosevelt sought therapeutic treatment and maintained sufficient political connections to reenter politics. In 1928, Roosevelt won election as governor of New York. He oversaw the rise of the Depression and drew from progressivism to address the economic crisis. During his gubernatorial tenure, Roosevelt introduced the first comprehensive unemployment relief program and helped to pioneer efforts to expand public utilities. He also relied on like-minded advisors. For example, Frances Perkins, then commissioner of the state’s Labor Department, successfully advocated pioneering legislation which enhanced workplace safety and reduced the use of child labor in factories. Perkins later accompanied Roosevelt to Washington and serve as the nation’s first female Secretary of Labor.22

On July 1, 1932, Roosevelt, the newly-designated presidential nominee of the Democratic Party, delivered the first and one of the most famous on-site acceptance speeches in American presidential history. Building to a conclusion, he promised, “I pledge you, I pledge myself, to a new deal for the American people.” Newspaper editors seized upon the phrase “new deal,” and it entered the American political lexicon as shorthand for Roosevelt’s program to address the Great Depression.23 There were, however, few hints in his political campaign that suggested the size and scope of the “New Deal.” Regardless, Roosevelt crushed Hoover. He won more counties than any previous candidate in American history. He spent the months between his election and inauguration traveling, planning, and assembling a team of advisors, the famous “Brain Trust” of academics and experts, to help him formulate a plan of attack. On March 4th, 1933, in his first Inaugural Address, Roosevelt famously declared, “This great Nation will endure as it has endured, will revive and will prosper. So, first of all, let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself—nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance.”24

Roosevelt’s reassuring words would have rung hollow if he had not taken swift action against the economic crisis. In his first days in office, Roosevelt and his advisers prepared, submitted, and secured Congressional enactment of numerous laws designed to arrest the worst of the Great Depression. His administration threw the federal government headlong into the fight against the Depression.

Roosevelt immediately looked to stabilize the collapsing banking system. He declared a national “bank holiday” closing American banks and set to work pushing the Emergency Banking Act swiftly through Congress. On March 12th, the night before select banks reopened under stricter federal guidelines, Roosevelt appeared on the radio in the first of his “Fireside Chats.” The addresses, which the president continued delivering through four terms, were informal, even personal. Roosevelt used his airtime to explain New Deal legislation, to encourage confidence in government action, and to mobilize the American people’s support. In the first “chat,” Roosevelt described the new banking safeguards and asked the public to place their trust and their savings in banks. Americans responded and across the country, deposits outpaced withdrawals. The act was a major success. In June, Congress passed the Glass-Steagall Banking Act, which instituted federal deposit insurance and barred the mixing of commercial and investment banking.25

Stabilizing the banks was only a first step. In the remainder of his “First Hundred Days,” Roosevelt and his congressional allies focused especially on relief for suffering Americans.26 Congress debated, amended, and passed what Roosevelt proposed. As one historian noted, the president “directed the entire operation like a seasoned field general.”27 And despite some questions over the constitutionality of many of his actions, Americans and their congressional representatives conceded that the crisis demanded swift and immediate action. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) employed young men on conservation and reforestation projects; the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) provided direct cash assistance to state relief agencies struggling to care for the unemployed;28 the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) built a series of hydroelectric dams along the Tennessee River as part of a comprehensive program to economically develop a chronically depressed region;29 several agencies helped home and farm owners refinance their mortgages. And Roosevelt wasn’t done.

The heart of Roosevelt’s early recovery program consisted of two massive efforts to stabilize and coordinate the American economy: the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA) and the National Recovery Administration (NRA). The AAA, created in May 1933, aimed to raise the prices of agricultural commodities (and hence farmers’ income) by offering cash incentives to voluntarily limit farm production (decreasing supply, thereby raising prices).30 The National Industrial Recovery Act, which created the National Recovery Administration (NRA) in June 1933, suspended antitrust laws to allow businesses to establish “codes” that would coordinate prices, regulate production levels, and establish conditions of employment to curtail “cutthroat competition.” In exchange for these exemptions, businesses agreed to provide reasonable wages and hours, end child labor, and allow workers the right to unionize. Participating businesses earned the right to display a placard with the NRA’s “Blue Eagle,” showing their cooperation in the effort to combat the Great Depression.31

The programs of the First Hundred Days stabilized the American economy and ushered in a robust though imperfect recovery. GDP climbed once more, but even as output increased, unemployment remained stubbornly high. Though the unemployment rate dipped from its high in 1933, when Roosevelt was inaugurated, vast numbers remained out of work. If the economy could not put people back to work, the New Deal would try. The Civil Works Administration (CWA) and, later, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) put unemployed men and women to work on projects designed and proposed by local governments. The Public Works Administration (PWA) provided grants-in-aid to local governments for large infrastructure projects, such as bridges, tunnels, schoolhouses, libraries, and America’s first federal public housing projects. Together, they provided not only tangible projects of immense public good, but employment for millions. The New Deal was reshaping much of the nation.32

The “Second” New Deal (1935-1936)

Facing reelection and rising opposition from both the left and the right, Roosevelt decided to act. The New Deal adopted a more radical, aggressive approach to poverty, the “Second” New Deal. In 1935, hoping to reconstitute some of the protections afforded workers in the now-defunct NRA, Roosevelt worked with Congress to pass the National Labor Relations Act (known as the Wagner Act for its chief sponsor, New York Senator Robert Wagner), offering federal legal protection, for the first time, for workers to organize unions. Three years later, Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act, creating the modern minimum wage. The Second New Deal also oversaw the restoration of a highly progressive federal income tax, mandated new reporting requirements for publicly traded companies, refinanced long-term home mortgages for struggling homeowners, and attempted rural reconstruction projects to bring farm incomes in line with urban ones.42

The labor protections extended by Roosevelt’s New Deal were revolutionary. In northern industrial cities, workers responded to worsening conditions by banding together and demanding support for worker’s rights. In 1935, the head of the United Mine Workers, John L. Lewis, took the lead in forming a new national workers’ organization, the Congress of Industrial Organizations, breaking with the more conservative, craft-oriented AFL. The CIO won a major victory in 1937 when affiliated members in the United Auto Workers struck for recognition and better pay and hours at a General Motors plant in Flint, Michigan. In the first instance of a “sit-down” strike, the workers remained in the building until management agreed to negotiate. GM recognized the UAW and the “sit-down” strike became a new weapon in the fight for workers’ rights. Across the country, unions and workers took advantage of the New Deal’s protections to organize and win major concessions from employers.

The signature piece of Roosevelt’s Second New Deal came the same year, in 1935. The Social Security Act provided for old-age pensions, unemployment insurance, and economic aid, based on means, to assist both the elderly and dependent children. The president was careful to mitigate some of the criticism from what was, at the time, in the American context, a revolutionary concept. He specifically insisted that social security be financed from payroll, not the federal government; “No dole,” Roosevelt said repeatedly, “mustn’t have a dole.”43 He thereby helped separate Social Security from the stigma of being an undeserved “welfare” entitlement. While such a strategy saved the program from suspicions, Social Security became the centerpiece of the modern American social welfare state. It was the culmination of a long progressive push for government-sponsored social welfare, an answer to the calls of Roosevelt’s opponents on the Left for reform, a response to the intractable poverty among America’s neediest groups, and a recognition that the government would now assume some responsibility for the economic well-being of its citizens. But for all of its groundbreaking provisions, the Act, and the larger New Deal as well, excluded large swaths of the American population.44

extension: “Second Inaugural Address of Franklin D. Roosevelt,” http://www.americanyawp.com/reader/23-the-great-depression/second-inaugural-address-of-franklin-d-roosevelt-1937/

Dana Cochran et al., “The Great Depression,” Matthew Downs, ed., in The American Yawp, Joseph Locke and Ben Wright, eds., last modified August 1, 2016, http://www.AmericanYawp.com.

Summary

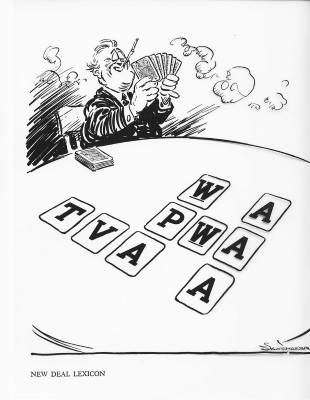

The New Deal produced so many new agencies, which were popularly known by their acronyms, that the Democrat Al Smith quipped that the American government had been “submerged in a bowl of alphabet soup.” In the first major wave of New Deal legislation in 1932, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA), the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA), the National Recovery Administration (NRA), the Civil Works Administration (CWA), the Works Progress Administration (WPA), and the Public Works Administration (PWA) all became major extensions of the federal bureaucracy. During the second major wave of New Deal legislation in 1935, the Social Security Act was passed, providing Americans with old-age pensions and unemployment insurance. The fact that Social Security remains a major component of the United States government illustrates that the New Deal continues to influence American life.

New Deal programs put many Americans back to work and provided at least some relief against the Great Depression. Nevertheless, the United States economy would not completely rebound from the depression until World War II, when the need for weapons shifted American industry back into high gear. And despite FDR’s personal popularity with the American public, his presidency and political ideology had produced vocal critics. Critics argued that FDR had assumed too much power, that some of his policies were unconstitutional, and that the Democratic Party’s approach to the economy produced a bureaucratic government that was too large and sapped the nation of the individualism and work ethic that had made America great for generations. Ideological battles over the size, scope, and mission of the United States federal government that first emerged during the New Deal are still prominent in contemporary American political discourse. After examining the Great Depression and the New Deal, what do you think? Was the New Deal necessary to combat the Great Depression, or does it represent government overreach and excessive bureaucratization?