7

After the Civil War, the United States struggled to mend the wounds of one of the bloodiest conflicts in American history. Most of the South lay in ruins, the slave system of Southern society had come to a violent end, and the president of the United States had been assassinated in cold blood. Reconstruction represented the United States government’s attempt to bring Southern states back into the fold of American government, and to develop a post-slavery South that recognized the citizenship rights of former slaves.

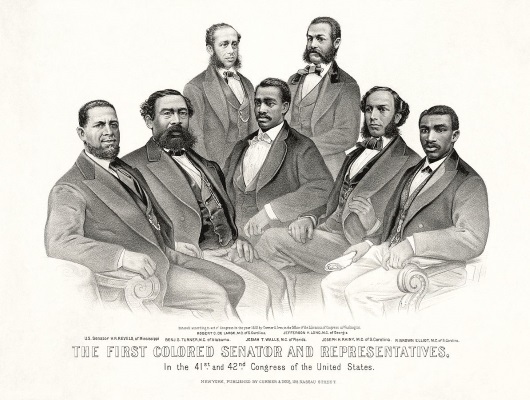

For a brief period of time between 1865 until 1877, progress on multiple fronts was evident. African-American political life, religious institutions, and educational institutions blossomed, and for the first time in American history, a significant number of African-Americans began playing a prominent role in Southern political and public life. Finally securing the right to vote, African-Americans elected members of their own communities into political office. In 1870, Hiram Revels was elected to represent Mississippi in the United States Senate, marking the first time an African-American was elected to Congress. Between 1869 and 1877, fourteen other African-Americans served in the House of Representatives, six African-Americans were elected as lieutenant governors, and nearly 600 African-Americans were elected to serve in state legislatures. During the same era, many African-American communities rushed to build public schools for African-American children who had been denied access to education in the pre-Civil War South. Several prominent African-American colleges, including Howard University in Washington D.C. and Fisk University in Tennessee, were also created, and African-American churches emerged practically overnight, finally giving African-Americans the ability to control their own religious institutions and practice their faith publicly.

Despite the significant gains African-Americans in the first decade after the Civil War, ultimately Reconstruction represented a failed revolution. After 1877, cultural and political backlash and domestic terrorism sponsored by groups like the Ku Klux Klan began to erode the political and social gains African-Americans had made after the Civil War. Why did Reconstruction ultimately fail? And were there major legacies of Reconstruction on American society?

Politics of Reconstruction

Reconstruction—the effort to restore southern states to the Union and to redefine African Americans’ place in American society—began before the Civil War ended. President Abraham Lincoln began planning for the reunification of the United States in the fall of 1863.2 With a sense that Union victory was imminent and that he could turn the tide of the war by stoking Unionist support in the Confederate states, Lincoln issued a proclamation allowing Southerners to take an oath of allegiance. When just ten percent of a state’s voting population had taken such an oath, loyal Unionists could then establish governments.3 These so-called Lincoln governments sprang up in pockets where Union support existed like Louisiana, Tennessee, and Arkansas. Unsurprisingly, these were also the places that were exempted from the liberating effects of the Emancipation Proclamation.

Initially proposed as a war aim, Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation committed the United States to the abolition of slavery. However, the Proclamation freed only slaves in areas of rebellion and left more than 700,000 in bondage in Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland, and Missouri as well as Union-occupied areas of Louisiana, Tennessee, and Virginia.

To cement the abolition of slavery, Congress passed the Thirteenth Amendment on January 31, 1865. The amendment and legally abolished slavery “except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.” Section Two of the amendment granted Congress the “power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.” State ratification followed, and by the end of the year the requisite three-fourths states had approved the amendment, and four million people were forever free from the slavery that had existed in North America for 250 years.4

Lincoln’s policy was lenient, conservative, and short-lived. Reconstruction changed when John Wilkes Booth shot Lincoln on April 14, 1865, during a performance of “Our American Cousin” at the Ford Theater. Treated rapidly and with all possible care, Lincoln succumbed to his wounds the following morning, leaving a somber pall over the North and especially among African Americans.

The assassination of Abraham Lincoln propelled Vice President Andrew Johnson into the executive office in April 1865. Johnson, a states’ rights, strict-constructionist and unapologetic racist from Tennessee, offered southern states a quick restoration into the Union. His Reconstruction plan required provisional southern governments to void their ordinances of secession, repudiate their Confederate debts, and ratify the Thirteenth Amendment. On all other matters, the conventions could do what they wanted with no federal interference. He pardoned all Southerners engaged in the rebellion with the exception of wealthy planters who possessed more than $20,000 in property.5 The southern aristocracy would have to appeal to Johnson for individual pardons. In the meantime, Johnson hoped that a new class of Southerners would replace the extremely wealthy in leadership positions.

Many southern governments enacted legislation that reestablished antebellum power relationships. South Carolina and Mississippi passed laws known as Black Codes to regulate black behavior and impose social and economic control. These laws granted some rights to African Americans, like the right to own property, to marry or to make contracts. But they also denied fundamental rights. White lawmakers forbade black men from serving on juries or in state militias, refused to recognize black testimony against white people, apprenticed orphan children to their former masters, and established severe vagrancy laws. Mississippi’s vagrant law required all freedmen to carry papers proving they had means of employment.6 If they had no proof, they could be arrested and fined. If they could not pay the fine, the sheriff had the right to hire out his prisoner to anyone who was willing to pay the tax. Similar ambiguous vagrancy laws throughout the South reasserted control over black labor in what one scholar has called “slavery by another name.”7 Black codes effectively criminalized black leisure, limited their mobility, and locked many into exploitative farming contracts. Attempts to restore the antebellum economic order largely succeeded.

These laws and outrageous mob violence against black southerners led Republicans to call for a more dramatic Reconstruction. So when Johnson announced that the southern states had been restored, congressional Republicans refused to seat delegates from the newly reconstructed states.

Republicans in Congress responded with a spate of legislation aimed at protecting freedmen and restructuring political relations in the South. Many Republicans were keen to grant voting rights for freed men in order to build a new powerful voting bloc. Some Republicans, like United States Congressman Thaddeus Stevens, believed in racial equality, but the majority were motivated primarily by the interest of their political party. The only way to protect Republican interests in the South was to give the vote to the hundreds of thousands of black men. Republicans in Congress responded to the codes with the Civil Rights Act of 1866, the first federal attempt to constitutionally define all American-born residents (except Native peoples) as citizens. The law also prohibited any curtailment of citizens’ “fundamental rights.”8

The Fourteenth Amendment developed concurrently with the Civil Rights Act to ensure its constitutionality. The House of Representatives approved the Fourteenth Amendment on June 13, 1866. Section One granted citizenship and repealed the Taney Court’s infamous Dred Scott (1857) decision. Moreover, it ensured that state laws could not deny due process or discriminate against particular groups of people. The Fourteenth Amendment signaled the federal government’s willingness to enforce the Bill of Rights over the authority of the states.

Based on his belief that African Americans did not deserve rights, President Johnson opposed both the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment and vetoed the Civil Rights Act, as he believed black Americans did not deserve citizenship. With a two-thirds majority gained in the 1866 midterm elections, Republicans overrode the veto, and in 1867, they passed the first of two Reconstruction Acts, which dissolved state governments and divided the South into five military districts. Before states could rejoin the Union, they would have to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment, write new constitutions enfranchising African Americans, and abolish black codes. The Fourteenth Amendment was finally ratified on July 9, 1868.

In the 1868 Presidential election, former Union General Ulysses S. Grant ran on a platform that proclaimed, “Let Us Have Peace” in which he promised to protect the new status quo. On the other hand, the Democratic candidate, Horatio Seymour, promised to repeal Reconstruction. Black Southern voters helped Grant him win most of the former Confederacy.

Reconstruction brought the first moment of mass democratic participation for African Americans. In 1860, only five states in the North allowed African Americans to vote on equal terms with whites. Yet after 1867, when Congress ordered Southern states to eliminate racial discrimination in voting, African Americans began to win elections across the South. In a short time, the South was transformed from an all-white, pro-slavery, Democratic stronghold to a collection of Republican-led states with African Americans in positions of power for the first time in American history.9

Through the provisions of the Congressional Reconstruction Acts, black men voted in large numbers and also served as delegates to the state constitutional conventions in 1868. Black delegates actively participated in revising state constitutions. One of the most significant accomplishments of these conventions was the establishment of a public school system. While public schools were virtually nonexistent in the antebellum period, by the end of Reconstruction, every Southern state had established a public school system.10 Republican officials opened state institutions like mental asylums, hospitals, orphanages, and prisons to white and black residents, though often on a segregated basis. They actively sought industrial development, northern investment, and internal improvements.

African Americans served at every level of government during Reconstruction. At the federal level, Hiram Revels and Blanche K. Bruce were chosen as United States Senators from Mississippi. Fourteen men served in the House of Representatives. At least two hundred seventy other African American men served in patronage positions as postmasters, customs officials, assessors, and ambassadors. At the state level, more than 1,000 African American men held offices in the South. P. B. S. Pinchback served as Louisiana’s Governor for thirty-four days after the previous governor was suspended during impeachment proceedings and was the only African American state governor until Virginia elected L. Douglass Wilder in 1989. Almost 800 African American men served as state legislators around the South with African Americans at one time making up a majority in the South Carolina House of Representatives.11

African American office holders came from diverse backgrounds. Many had been born free or had gained their freedom before the Civil War. Many free African Americans, particularly those in South Carolina, Virginia, and Louisiana, were wealthy and well educated, two facts that distinguished them from much of the white population both before and after the Civil War. Some like Antione Dubuclet of Louisiana and William Breedlove from Virginia owned slaves before the Civil War. Others had helped slaves escape or taught them to read like Georgia’s James D. Porter.

The majority of African American office holders, however, gained their freedom during the war. Among them were skilled craftsman like Emanuel Fortune, a shoemaker from Florida, minsters such as James D. Lynch from Mississippi, and teachers like William V. Turner from Alabama. Moving into political office was a natural continuation of the leadership roles they had held in their former slave communities.

By the end of Reconstruction in 1877, more than 2,000 African American men had served in offices ranging from mundane positions such as local Levee Commissioner to United States Senator.12 When the end of Reconstruction returned white Democrats to power in the South, all but a few African American office holders lost their positions. After Reconstruction, African Americans did not enter the political arena again in large numbers until well into the twentieth century.

Extension: a letter from a former slave to his former master: http://www.americanyawp.com/reader/reconstruction/jourdon-anderson-writes-his-former-master-1865/

Christopher Abernathy et al., “Reconstruction,” Nicole Turner, ed., in The American Yawp, Joseph Locke and Ben Wright, eds., last modified August 1, 2016, http://www.americanyawp.com/text/15-reconstruction/.

Summary

Commenting on the failure of Reconstruction, the famous African-American sociologist and civil rights activist W. E. B. Du Bois stated, “the slave went free; stood a brief moment in the sun; then moved back again toward slavery.” Ultimately, two major factors contributed to the failure of Reconstruction after the Civil War. First, two hundred years of slavery had deeply ingrained racism into Southern society, and many white Southerners, especially former slave owners, reacted violently against the development of African-American political power. Since the pre-Civil War South had also become heavily dependent on slave labor, many wealthy Southerners also were not willing to transition to the post-Civil War capitalist system. The other major factor that contributed to the failure of Reconstruction was that, over time, Northern Republicans simply lost the political will to reshape the South. Although Radical Republicans advocated a forcible Reconstruction of Southern life, in general the Republican Party chose a much more moderate path toward Southern Reconstruction, at least in part because of widespread Northern concern that the tensions that had ignited the Civil War could break out again. When the North began facing an economic recession by the end of the 1870s, the national focus on Southern political life shifted. By 1877, the last remaining American troops who had been stationed in the South in order to protect African-American citizenship rights and secure Southern politics against electoral fraud were withdrawn. Southern white Democrats, and many of the former plantation elite, returned to power in the South, and immediately set about to dismantling the gains of Reconstruction.

Although Reconstruction largely failed, it did have some positive developments for African-Americans in the South. The slave system, of course, had been dismantled, and African-Americans had new opportunities to develop their own political, educational, and religious institutions. However, the advent of Jim Crow laws and the power of terrorist groups like the Ku Klux Klan plunged the South back into an overtly racist, segregated society. The Southern economy would not fully recover from the Civil War until the 1930s, and African-Americans in the South would largely be denied full citizenship rights in the South until the 1960s.