30

The 1950s were a decade of prosperity. The decade’s economic growth and the continued expansion of the middle class seemed to promise ever higher standards of living. But things began to fall apart by the end of the decade. Wracked by contradiction, dissent, discrimination, and inequality, American society stood on the precipice of revolution. Even before the decade ended, the century old struggle for African American citizenship rights had developed into a full scale protest movement. Increasing Cold War tensions led to further American military action overseas, most notably in Vietnam. As the financial and human cost of this war escalated, so too did opposition. Civil Rights activism and anti-war sentiment, fueled a rights revolution that challenged Americans’ definitions of American freedoms and citizenship rights.

Amidst a social revolution, came a political upheaval. A decade of economic prosperity in the 1950s was followed by the increasing support of the rights revolution and social welfare programs by the federal government through Johnson’s Great Society in the early 1960s. Some Americans saw this spending on social welfare as the federal government’s support of the minority at the expense of the majority. This led many Americans to reject the government’s strong hand in the economy. Richard Nixon campaigned in 1968 as the defender of the Silent Majority, “the non-shouters”, the “non-protesters.” His election ushered in a period of conservative politics that promoted a smaller government and deregulation.

At the same time the American economy was shifting as industry moved overseas and the service sector continued to grow. Continuing emphasis on a Cold War ideology promoted both the development of industry outside of the United States and a steady military buildup, resulting in the loss of domestic industry and deficit government spending. Deindustrialization, a growing service economy, and a push for less government regulation all worked to increase the wealth gap among Americans in the coming decades.

Rising Wealth and Inequality

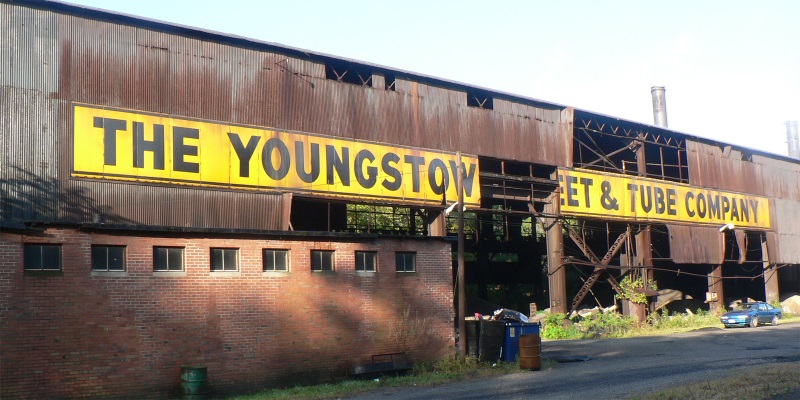

Deindustrialization

During the 1950s, Americans of all classes benefited from postwar prosperity. However, segregation and discrimination perpetuated racial and gender inequalities, but unemployment continually fell and working class standards-of-living nearly doubled between 1947 and 1973.

But, general prosperity masked deeper vulnerabilities. Detroit offers the best example of the decline of American industry and the creation of an intractable “urban crisis.” Detroit boomed during the wartime economy of the 1940s.

After the war, however, automobile firms began closing urban factories and moving to outlying suburbs. Several factors fueled the process:

- Municipal governments banished industry to make room for high-rise apartments and office buildings.

- Mechanization

- Manufacturing firms sought areas with “business friendly” policies such as:

- low tax rates,

- anti-union “right-to-work” laws

- low wages.

Between 1953 and 1960, East Detroit lost 10 plants and over 71,000 jobs. When auto companies mechanized or moved their operations, ancillary suppliers were cut out of the supply chain and forced to cut their own workforce. Between 1947 and 1977, the number of manufacturing firms in the city dropped by more than 1000. Manufacturing jobs fell from 338,400 to 153,000 over the same three decades.

Industrial restructuring decimated all workers, but deindustrialization fell heaviest on the city’s African Americans. Although many middle class blacks managed to move out of the city’s ghettos, by 1960, 19.7 percent of black autoworkers in Detroit were unemployed, compared to just 5.8 percent of whites. Segregation and discrimination kept them stuck where there were fewer and fewer jobs. Over time, Detroit devolved into a mass of unemployment, crime, and crippled municipal resources. When riots rocked Detroit in 1967, 25 to 30 percent of African American residents between age eighteen and twenty-four were unemployed.

An Assault on Unions

Deindustrialization also went hand in hand with growing anti-unionism. Lacking the political support they had enjoyed during the New Deal, unions such as the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) and the United Auto Workers (UAW) shifted tactics and accepted labor-management accords which promoted cooperation, not agitation.

This accord held mixed results for workers:

Positive Results:

- Management offered privatized welfare systems with health benefits and pensions.

- Workers could push for better conditions through grievance arbitration and collective bargaining

Negative Results:

- Bureaucracy and corruption alienated unions from workers and the general public.

- Union management came to hold primary influence rather than workers.

Workers by necessity pursued a more moderate agenda compared to earlier union members.

While conservative critiques of unions worked to undermine the labor movement, labor’s decline also coincided with ideological changes within American liberalism. By the 1960s, many liberals had forsaken working class politics. More and more saw poverty as stemming not from structural flaws in the national economy, but from the failure of individuals to take full advantage of the American system.

Internal racism also weakened the labor movement. In Detroit and elsewhere after World War II, white workers participated in “hate strikes” where they walked off the job rather than work with African Americans.

By the end of the 20th century, labor lost its foothold in the marketplace. Where unions represented a third of the workforce in the 1950s, by 2015 only one in ten workers belonged to a union.

Rise of the Sun Belt

Geography also impacted labor’s fall as American firms fled pro-labor states in the 1970s and 1980s. Some went overseas in the wake of new trade treaties to employ low-wage foreign workers, but others turned to anti-union states in the South and West. Factories shuttered in the North and Midwest, leading commentators to dub America’s former industrial heartland the “the Rust Belt,” contrasted to the prosperous and dynamic “Sun Belt.”

The Taft-Hartley Act in 1947 facilitated southern states’ frontal assault on unions. Thereafter, cheap, non-unionized labor, low wages, and lax regulations pulled industries away from the Rust Belt. Skilled northern workers followed the new jobs southward and westward, lured by cheap housing and a warm climate.

In the South middle class whites grew prosperous, but often these were not native southerners. As the cotton economy shed farmers and laborers, poor white and black southerners found themselves excluded from the Sun Belt industrialization. Public investments were scarce. White southern politicians channeled federal funding away from primary and secondary public education and toward high-tech industry and university-level research. The Sun Belt inverted Rust Belt realities: the South and West had growing numbers of high-skill, high-wage jobs but lacked the social and educational infrastructure needed to train native poor and middle-class workers for those jobs.

Stagflation

By mid-1970, a recession hit. President Nixon proposed a budget with an $11 billion deficit in 1971 with the hope that more federal funds in the economy would stimulate investment and job creation. When the unemployment rate refused to budge, the following year he proposed a budget with a $25 billion deficit. At the same time, he tried to fight continuing inflation by freezing wages and prices for 90 days, which proved to be only a temporary fix. The combination of unemployment and rising prices is known as “stagflation”—a term that combined the economic conditions of stagnation and inflation. The origins of which went beyond policy to include:

– Post-war industrial development in Asia and Western Europe.

– American appetites for imports

– In 1971, President Nixon allowed the value of the dollar to float freely against the price of gold (which caused an immediate 8% devaluation of the dollar.)

– American goods became cheaper abroad and stimulated exports.

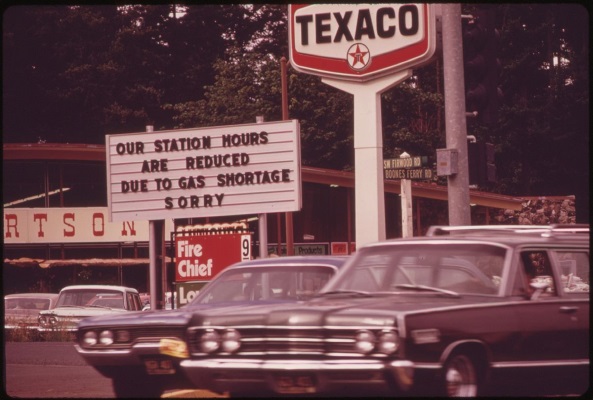

The situation was made worse when the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) imposed an embargo on oil shipments to the United States from 1973 to 1974 in response to US support of Israel in a war with Egypt and Syria. This caused an oil shortage, which affected both gas prices and the prices of goods manufactured and transported using on oil or gas.

American consumers panicked. Gas stations limited the amount customers could purchase and closed on Sundays. Even after the embargo ended, prices continued to rise, and by 1974, inflation had soared.

In January of 1977, Carter became president of a nation in the midst of economic turmoil. Oil shocks, inflation, stagnant growth, unemployment, and sinking wages weighed down the nation’s economy. Unemployment reached 7.8% in 1980, up from 6% at the start of Carter’s term. Inflation jumped from 6% in 1978 to a staggering 20% by 1980.

The administration responded in fundamentally conservative ways.

- Congress passed tax cuts for the upper-middle class.

- The White House deregulated the airline and trucking industries.

- Carter proposed balancing the federal budget.

- To halt inflation, the Federal Reserve raised interest rates and tightened the money supply—policies designed to reduce inflation in the long run but which increased unemployment in the short run.

Reagan & the Economy: Beyond Reaganomics

Speaking to Detroit autoworkers in 1980, Republican presidential candidate Ronald Reagan described the American Dream under Carter. The family garage may still hold two cars, cracked Reagan, but they were “both Japanese and they’re out of gas.” The former governor of California suggested a once-proud nation was running on empty. Reagan stressed the theme of “national decline” in his campaign and promised to make the United States great once again through tax cuts and reduced government spending.

Reagan failed to reduce government spending. Rather he grew it by creating a new cabinet-level agency, the Department of Veterans Affairs, thus increasing the number of federal employees. He allocated a smaller share of the federal budget to anti-poverty programs, but Social Security and Medicare entitlements were left largely untouched except for an increase in payroll taxes to pay for them.

Reagan did work to deregulate industry and weaken labor unions. Banks and savings and loan associations were deregulated. Enforcement of pollution control by the Environmental Protection Agency lessened, and restrictions on logging and drilling for oil on public lands were relaxed. Believing the free market was self-regulating, the administration had little use for labor unions. In 1981, the president fired twelve thousand federal air traffic controllers who had gone on strike to secure better working conditions (which would also have improved the public’s safety). His action effectively destroyed the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO) and ushered in a new era of labor relations in which employers simply replaced striking workers. The weakening of unions contributed to the leveling off of real wages for the average American family during the 1980s.

Reagan’s economic policies succeeded in breaking the cycle of stagflation, but at significant cost. In its effort to curb high inflation with dramatically increased interest rates, the Federal Reserve also triggered a deep recession. Inflation did drop, but borrowing became expensive and consumers spent less. In Reagan’s first years in office, bankruptcies increased and unemployment reached 10%, its highest level since the Great Depression. Homelessness became a significant problem in cities, a fact the president made light of by suggesting that the press exaggerated the problem and that many homeless people chose to live on the streets.

Economic growth resumed in 1983 and gross domestic product grew at an average of 4.5 percent during the rest of his presidency. By the end of Reagan’s second term in office, unemployment had dropped to about 5.3 percent, but the nation was nearly $3 trillion in debt.

OpenStax, U.S. History. OpenStax CNX. Jul 27, 2017 http://cnx.org/contents/a7ba2fb8-8925-4987-b182-5f4429d48daa@3.84; and Wright, Ben and Joseph Locke, Eds.(2017). The American Yawp. Retrieved from http://www.americanyawp.com/index.html

With adjustments by Margaret Carmack.

Extension: An audio explanation of Reaganomics.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IrPneXmPNyE&t=35s

The Audiopedia.(October 4, 2016) What is Reaganomics? [Video File] Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IrPneXmPNyE&t=35s

Extension: Explanation of 1970s economic downturn (please watch through 14:12min)

Saylor Academy (February 24, 2012). Saylor.org Hist212: “The 1970s An Age of Crisis.[Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_nNsSXffTLg

Summary

By the mid-1970s, widely-shared postwar prosperity leveled off and began to retreat. Growing international competition, technological inefficiency, and declining productivity gains stunted working- and middle-class wages. As the country entered recession, wages decreased and the pay gap between workers and management began its long widening.

The government and business policies that had allowed for prosperity in the 1950s laid the groundwork for de-industrialization and stagflation in the following decades. Combined with rising federal deficits due to military spending and Johnson’s expansion of the welfare state established by FDR and the New Deal, the struggling American economy and rising wealth gap helped to usher in a wave of conservatism that resulted in the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980.

Reagan’s superior rhetorical skills enabled him to gain widespread support for his plans for the nation. Implementing a series of economic policies dubbed “Reaganomics,” the president sought to stimulate the economy while shrinking the size of the federal government and providing relief for the nation’s wealthiest taxpayers. During his two terms in office, he cut spending on social programs, but increased spending on defense. While Reagan was able to break the cycle of stagflation, his policies also triggered a recession, plunging the nation into a brief period of significant unemployment, and made a balanced budget impossible. In the end, Reagan’s policies diminished many Americans’ quality of life while enabling more affluent Americans to prosper

Battered but intact, the social welfare programs of the New Deal and Great Society (for example, Social Security, Medicaid, and Aid to Families With Dependent Children) did survive the 1980s. Despite Republican vows of fiscal discipline, both the federal government and the national debt ballooned. The nation entered another recession in the early 1990s which Reagan’s successor, George H. W. Bush, was unable to pull the nation out of before the 1992 election, paving the way for the election of Democrat Bill Clinton.