31

“It’s the Economy, Stupid” read the sign posted prominently in the Clinton campaign headquarters in 1992. Taking place in the midst of a recession, Bill Clinton worked to focus the debate in the 1992 Presidential campaign on economic issues. The policies of Reagan and then Bush had led to recession and a continued rise in economic inequality. Clinton described himself as a “New Democrat,” one that favored free trade and deregulation, but also promised the middle class higher taxes on the rich and reform of the welfare system.

Clinton’s administration oversaw the longest period of economic expansion in the nation’s history. This near decade-long period of economic expansion was in large part thanks to a boom in the technology industry. However, deregulation and speculative investment led to a burst in this tech bubble that resulted in a recession at the turn of the 21st century.

By this point, America had again returned to a conservative president in George W. Bush, son of the former president George H. W. Bush. Much of the Bush presidency was dominated by domestic crisis beginning with the September 11th attacks in his first term and then in his second term the Hurricane Katrina disaster. But on the economic front, Bush continued previous conservative economic policies of tax cuts and deregulation. This combined with the deregulation of the banking industry during the Clinton presidency led to a burst in the so called “housing bubble” and the onset of the Great Recession of 2008.

Democrat Barack Obama found himself entering office in the midst of two unpopular foreign wars and an economic recession. Drawing on the lessons of his Democratic forbearers, Obama proposed a new New Deal aimed at stabilizing the economy and bringing back American prosperity in the continuing cycle of economic boom and bust in the United States.

Recent Cycles of Boom and Bust

Clinton and the New Economy

Clinton took office with an economy in recession. His administration’s plans for fixing the economy included:

- limiting spending

- cutting the budget to reduce the nation’s deficit

- keeping interest rates low to encourage private investment

- eliminating protectionist tariffs.

He expanded the Earned Income Tax Credit, lowering tax obligations of working families who were just above the poverty line. Addressing the budget deficit, Congress passed the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993 without a single Republican vote. The act raised taxes for the top 1.2%, lowered them for fifteen million low-income families, and offered tax breaks to 90% of small businesses. Vice President Al Gore worked to slash business regulation leaving the federal regulatory apparatus intact, but allowing greater flexibility for the private economy to function.

Clinton also supported ratification of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), a treaty that eliminated tariffs and trade restrictions among the United States, Canada, and Mexico. The treaty had been negotiated by the Bush administration, but, because of labor opposition and some in Congress who feared the loss of jobs to Mexico, the treaty had not been ratified. To allay the concerns of unions, Clinton added an agreement to protect workers. Congress ratified NAFTA in 1993.

During Clinton’s administration, job growth increased and the deficit shrank. Increased tax revenue and budget cuts turned the annual national budget deficit to a record budget surplus in 2000. Reduced government borrowing freed up capital for private-sector use, and lower interest rates fueled growth. During the Clinton years, inflation dipped to 2.3% and the unemployment rate declined, reaching a thirty-year low of 3.9% in 2000.

The Tech Boom

The world and the economy were transformed in the 1990s with the advent of new technologies, which were a crucial factor in economic expansion and increasing productivity. These technologies included the personal computer, advances in telecommunications, improved cell phones, software, and the World Wide Web, which connected Americans across the world to the internet. In 1994, the Clinton administration became the first to launch an official White House website.

Throughout the decade, there was increased investment in companies in the technology sector. Stock shares rose dramatically and many start-ups were created. Many talked of new business models, claimed that improvements in computer hardware and software would dramatically change the future, and that information was now the most valuable thing in the economy.

In financial markets, a “dot-com bubble” brought an increase in Initial Public Offerings (IPOs, or the first sale of stock by a private company) and the prevalent use of stock options. Markets even began to value dot-com stocks over established firms.

Bush Economy

This led to an unstable investment market that burst in 2000 resulting in a sharp drop in the U.S. stock market. The ensuing recession triggered millions of jobs losses over the next two years. In response, the Federal Reserve cut interest rates to historic lows to encourage consumer spending. By 2002, the economy seemed to be stabilizing somewhat, but few of the lost manufacturing jobs were restored. Instead, the “outsourcing” of jobs to China and India became an increasing concern. In response, the newly elected President George W. Bush turned to supply-side economics, which argued that tax cuts for the wealthy would allow them to invest more and create jobs for everyone else.

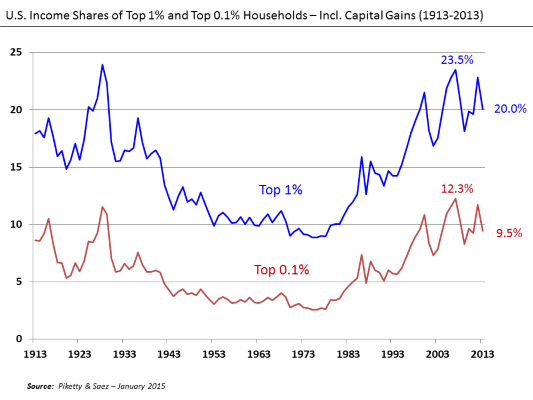

The cuts were controversial; the rich got richer while the middle and lower classes bore a proportionally larger share of the nation’s tax burden. By 2005, dramatic examples of income inequity were increasing; the chief executive of Wal-Mart earned $15 million that year, roughly 950 times what the company’s average associate made. Even as productivity climbed, workers’ incomes stagnated.

The Great Recession

Notwithstanding economic growth in the 1990s and steadily increasing productivity, wages had remained largely flat relative to inflation since the end of the 1970s. To compensate, many consumers were buying on credit. With low interest rates, financial institutions were eager to oblige them. By 2008, credit card debt was over $1 trillion. More importantly, banks were making high-risk, high-interest mortgage loans called subprime mortgages to consumers who lacked the ability to make the required payments.

These subprime loans had a devastating impact on the larger economy. In the past, banks carefully vetted buyers for their ability to pay back loans with interest, as this was how the bank would make money. However, decades of financial deregulation had rolled back restraints and enabled risky business practices. In the 1990s, Bill Clinton signed the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, repealing provisions of the 1933 Glass-Steagall Act separating commercial and investment banks, and the Commodity Futures Modernization Act, which exempted credit-default swaps–perhaps the key financial mechanism behind the crash–from regulation. This allowed lending institutions to sell their loans as bonds, thus separating the financial interests of the lender from the ability of the borrower to repay. In other words, banks could afford to make bad loans, because they could sell them and not suffer the financial consequences when borrowers failed to repay.

Once they had purchased the loans, larger investment banks bundled them into huge packages known as collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) and sold them to investors around the world. This system greatly swelled the housing loan market, especially the market for subprime mortgages. The result was a housing bubble, in which the value of homes rose year after year based on the ease with which people could now buy them.

When the real estate market stalled in 2007, the bubble burst. People began to default on their loans, and more than one hundred mortgage lenders went out of business. American International Group (AIG), a multinational insurance company that had insured many of the investments, faced collapse. Other large financial institutions found themselves in danger, as they were either besieged by demands for payment or found their demands on their own insurers unmet. The prestigious investment firm Lehman Brothers was completely wiped out in September 2008.

Realizing that the failure of major financial institutions could result in the collapse of the entire U.S. economy, the chairman of the Federal Reserve, Ben Bernanke, authorized a bailout of the Wall Street firm Bear Stearns. Members of Congress met with Bernanke and Secretary of the Treasury Henry Paulson in September 2008 to find a way to head off the crisis. They agreed to use $700 billion in federal funds to bailout troubled institutions, and Congress subsequently passed the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act, creating the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP). One important element of this program was aid to the auto industry. The Bush administration responded to their appeal with an emergency loan of $17.4 billion to stave off the industry’s collapse.

The actions of the Federal Reserve, Congress, and the president prevented the complete disintegration of the nation’s financial sector and warded off a scenario like that of the Great Depression. However, the bailouts could not prevent a severe recession in the U.S. and world economy. As people lost faith in the economy, stock prices fell by 45%. Unable to receive credit from now-wary banks, smaller businesses found that they could not pay suppliers or employees. Home values decreased, and owners were unable to borrow against them to pay off other obligations, such as credit card debt or car loans. More importantly, millions of homeowners who had expected to sell their houses at a profit and pay off their adjustable-rate mortgages were now stuck in houses with values shrinking below their purchasing price and forced to make mortgage payments they could no longer afford.

Without access to credit, consumer spending declined. As the Great Recession of 2008 deepened, the situation of ordinary citizens became worse. During the last four months of 2008, one million American workers lost their jobs, and during 2009, another three million found themselves out of work. Under such circumstances, many resented the federal bailout. It seemed as if the wealthiest were being rescued by the taxpayer from the consequences of their imprudent and even corrupt practices.

Obama & Economic Recovery

Barack Obama had been elected on a platform of healthcare reform and a wave of frustration over the sinking economy. Obama took charge of the TARP program distributing some $7.77 trillion designed to help shore up the nation’s banking system. Recognizing that the economic downturn also threatened major auto manufacturers in the United States, he sought and received congressional authorization for $80 billion to help Chrysler and General Motors. The action was controversial, but it did help the automakers earn a profit by 2011. It also helped prevent layoffs and wage cuts. By 2013, the automakers had repaid over $50 billion of bailout funds. Finally, through the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), the administration spent almost $800 billion to stimulate economic growth and job creation.

Many other Americans continue to be challenged by the state of the economy. The nation struggled to maintain a modest annual growth rate of 2.5 percent after the Great Recession, and the percentage of the population living in poverty continues to hover around 15 percent. Income has decreased, and, as late as 2011, the unemployment rate was still high in some areas. Eight million full-time workers have been forced into part-time work, whereas 26 million seem to have given up and left the job market.

OpenStax, U.S. History. OpenStax CNX. Jul 27, 2017 http://cnx.org/contents/a7ba2fb8-8925-4987-b182-5f4429d48daa@3.84; Wright, Ben and Joseph Locke, Eds.(2017). The American Yawp. Retrieved from http://www.americanyawp.com/index.html; Roodvoets, Jacob. (December 1, 2014). America’s Economy in the 1990s. Retrieved from http://econhist.econproph.net/2014/12/americas-economy-in-the-1990s/; and Boundless. ( N.D.) The “New Economy” of the 1990s.Retrieved from https://www.boundless.com/u-s-history/textbooks/boundless-u-s-history-textbook/bush-clinton-and-a-changing-world-31/the-clinton-administration-231/the-new-economy-of-the-1990s-1320-6482/ with adjustments by Margaret Carmack.

Extension: Bill Clinton discusses NAFTA and his views on deregulation.

William J. Clinton, “Remarks on Signing the North American Free Trade Agreement Implementation Act,” December 8, 1993. Available online via The American Presidency Project (http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=46216); Source: William J. Clinton, “Statement on Signing the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act,” November 12, 1999. Available online via The American Presidency Project(http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=56922); Source: William J. Clinton, “Statement of Administration Policy: H.R. 4541 – Commodity Futures Modernization Act of 2000,” October 19, 2000. Available online via The American Presidency Project(http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=74825)

Extension: Chart of employment numbers during 21st century recessions.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:US_employment_1995-2012.png

Federal Reserve Bank of S. Louis (2012). Civilian Employment-Population Ratio. Licensed Under Creative Commons on commons.wikimedia.org

Extension: An explanation of the causes of the financial crisis (only watch the first minute)

Vlogbrothers. (December 4, 2015). The Explain The 2008 Financial Crisis Challenge! [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2nVregoa654

Summary

The 21st century began with the nation in recession after the longest period of economic growth in the nation’s history. When George W. Bush took office in January 2001, he was committed to a Republican agenda. He cut tax rates for the rich and tried to limit the role of government in people’s lives, in part by providing students with vouchers to attend charter and private schools and encouraging religious organizations to provide social services instead of the government. While his tax cuts pushed the United States into a chronically large federal deficit, reversing the work of his predecessor, many of his supply-side economic reforms stalled during his second term.

Largely as a result of a deregulated bond market and dubious innovations in home mortgages, the nation reached the pinnacle of a real estate boom in 2007. And the markets collapsed in 2008. The threatened collapse of the nation’s banks and investment houses required the administration to extend aid to the financial sector. Through the TARP and ARRA programs, President Obama, elected in 2008, followed through on the bailout policy of his predecessor.

Many resented this bailout of the rich, as ordinary citizens lost jobs and homes in the Great Recession of 2008. The recessions and subsequent bailouts of the 21st century have left many American feeling as though the system is rigged against them. The economic inequality and wealth gap that developed in the 1960s has only continued to grow over the last half-century.

Since the New Deal, the federal government has taken a hand in the American economy. But depending on the administration and the state of the economy when they enter office, the strength of that hand has ebbed and flowed since the 1930s. While the basic structure of the welfare state put in place by FDR and then Johnson has remained intact, the size and scope of those programs continues to fluctuate and remains at the center of political debates today.