34

World War I redrew the map of Europe, toppling empires, creating new nations, and sparking national tensions that would burn for generations. Just as America had been looking to expand its international presence at the turn of the 20th century, so too had European nations looked to expand their imperial power, Germany chief among them. As the German empire expanded its power and influence, the nations of Europe began to form strategic alliances. Across the Atlantic, Americans were reticent to get involved in European affairs, beyond promoting the expansion of transatlantic trading. President Woodrow Wilson, elected in 1912, was notably different from his predecessors in his vision of American foreign policy. Wilson promised not to rely on the Roosevelt Corollary, favoring a less interventionist stance, particularly in Latin America.

But as a rebellion in Mexico threatened US interests and the war in Europe heated up, Wilson found it increasingly difficult to avoid American intervention to protect US interests. Wilson declared the United States neutral as war broke out in Europe. But very early on, American actions challenged the true nature of that neutrality. The American economy was quickly becoming the largest industrial economy in the world. The continued economic success of the United States relied on continued trade with Europe, particularly Great Britain and France. As German U-Boats wreaked havoc on American shipping and the German government tried to entice Mexico into a war with the US, public opinion began to shift in favor of involvement in war. Wilson found it increasingly difficult to justify his policy of neutrality.

In April of 1917, Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany. Over the next year and half American troops provided much needed support to British and French troops. When armistice was declared on November 11, 1918, the US had lost just under 117,000 men. A small number compared to those lost by Britain and France. But when considered in conjunction with the $32 billion spent fighting the war, the Great War, as it was called at the time, had taken a great toll on the United States.

Isolation and World War I

Woodrow Wilson’s New Freedom

When Woodrow Wilson took over the White House in March 1913, he shared the commonly held view that American values were superior to those of the rest of the world, that democracy was the best system to promote peace and stability, and that the United States should continue to actively pursue economic markets abroad. But he proposed an idealistic foreign policy based on morality, rather than American self-interest, and felt that American interference should occur only when the circumstances rose to the level of a moral imperative.

Wilson promised not to rely on the Roosevelt Corollary and reduce overseas interventions. Once president, however, Wilson found that it was more difficult to avoid American interventionism in practice than in rhetoric. Overall, Wilson intervened more in Western Hemisphere affairs than his predecessors. In 1915, a revolution in Haiti threatened the safety of New York banking interests in the country, Wilson sent over 300 U.S. Marines to establish order. Subsequently, the United States assumed control over the island’s foreign policy as well as its financial administration. In 1916, Wilson sent marines to the Dominican Republic to ensure prompt payment of a debt that nation owed. In 1917, Wilson sent troops to Cuba to protect American-owned sugar plantations from attacks by Cuban rebels.

Wilson’s most noted foreign policy foray prior to World War I focused on Mexico, where rebel general Victoriano Huerta had seized control. Wilson refused to recognize Huerta’s government, instead demanding that Mexico hold democratic elections and establish laws based on the moral principles Wilson espoused. Officially, Wilson supported Venustiano Carranza, who opposed Huerta. When American intelligence learned of a German ship allegedly preparing to deliver weapons to Huerta’s forces, Wilson ordered the U.S. Navy to stop the shipment.

On April 22, 1914, a fight erupted between the U.S. Navy and Mexican troops, resulting in nearly 150 deaths, 19 of them American. Although Carranza’s faction managed to overthrow Huerta that summer, most Mexicans—including Carranza—had come to resent American intervention. Carranza refused to work with Wilson. Wilson then turned to support rebel forces who opposed Carranza, most notably Pancho Villa. However, Villa lacked strength in number or weapons; in 1915, Wilson reluctantly authorized official U.S. recognition of Carranza’s government.

War Erupts In Europe

The events that pushed Europe into war seemed removed from U.S. interests. But German military action and the US’s economic ties to Germany’s enemies eventually pulled them into war.

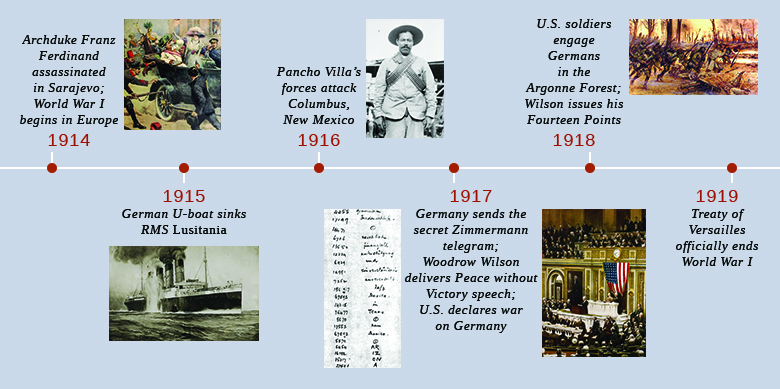

By early 1915, Germany dispatched a fleet of their new technological, the German unterseeboot—an “undersea boat” or U-boat—around Great Britain to attack both merchant and military ships. The U-boats acted in direct violation of international law, attacking without warning from beneath the water instead of surfacing and permitting the surrender of civilians or crew. By 1918, German U-boats had sunk nearly 5000 vessels, including the RMS Lusitania, on its way from New York to Liverpool on May 7, 1915. The German Embassy in the United States had announced that this ship would be subject to attack for its cargo of ammunition. Almost 1,200 civilians died in the attack, including 128 Americans. The attack horrified the world, galvanizing support for the war. This attack, more than any other event, would test President Wilson’s desire to stay out of the European conflict.

The Challenge of Neutrality

In his message to Congress in 1914, Wilson stated, “Every man who really loves America will act and speak in the true spirit of neutrality, which is the spirit of impartiality and fairness and friendliness to all concerned.”

Despite the loss of American lives on the Lusitania, President Wilson stuck to neutrality:

- in part out of moral principle,

- in part as a matter of practical necessity,

- in part for political reasons.

Few Americans wanted to get involved in a war in Europe, and Wilson did not want to risk losing his reelection by ordering an unpopular military intervention. It was already a difficult reelection bid. Wilson felt pressure from different political constituents to take a position on the war, yet he knew that elections were seldom won with a campaign promise of “If elected, I will send your sons to war!” Rather, Wilson agreed to a “preparedness campaign.” This campaign included the passage of the National Defense Act of 1916, which more than doubled the size of the army to 225,000, and the Naval Appropriations Act of 1916, which called for the expansion of the U.S. fleet, including battleships, destroyers, submarines, and other ships.

As the 1916 election approached, Wilson capitalized on neutrality campaigning under the slogan “Wilson—he kept us out of war.” The election was a close call on election night. Only when a tight race in California was decided two days later could Wilson claim victory. Despite his victory based upon a policy of neutrality, Wilson would find true neutrality a difficult challenge. Several different factors pushed Wilson, however reluctantly, toward the inevitability of American involvement.

Wilson’s “neutrality” had not meant total isolation. The United States continued commercial ties with all belligerents. So, a key factor driving U.S. engagement was economics. Great Britain was the country’s most important trading partner, and the Allies as a whole relied heavily on American imports. The value of all exports to the Allies quadrupled from $750 million to $3 billion in the first two years of the war. At the same time, the British naval blockade meant that exports to Germany all but ended, dropping from $350 million to $30 million. Likewise, numerous private banks in the United States made extensive loans—in excess of $500 million—to England.

- Another key factor in the decision to go to war were the deep ethnic divisions between native-born Americans and more recent immigrants:

- Anglo-Saxon descendents felt a continued connection with Great Britain.

- Irish-Americans resented British rule over their place of birth and opposed support for the British empire.

- Many Jewish immigrants had fled anti-Semitic pogroms in Tsarist Russia, thus supported any nation fighting that authoritarian state.

- German Americans saw Germany as a victim of British and Russian aggression and French desires to settle old scores

- Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire immigrants were mixed in their sympathies

For interventionists, this lack of support for Great Britain and its allies among recent immigrants only strengthened their conviction.

Germany’s continued use of submarine warfare also challenged U.S. neutrality. Germany had promised to restrict their use of submarine warfare after 1915. Instead, in February 1917, Germany intensified submarine attacks in an effort to end the war quickly before Great Britain’s naval blockade starved them out of food and supplies and before the United States could intervene and tip the balance of war. In February 1917, a German U-boat sank the American merchant ship, the Laconia, killing two passengers, and, in late March, quickly sunk four more American ships. These attacks increased pressure on Wilson from all sides, as government officials, the general public, and both Democrats and Republicans urged him to declare war.

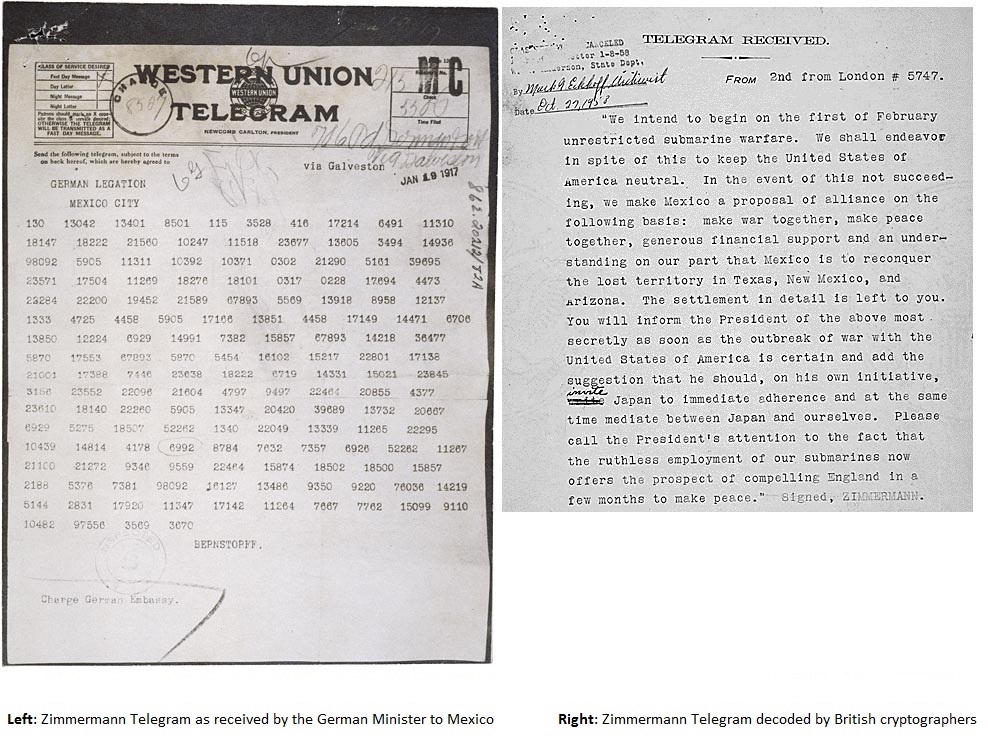

The final element that led to American involvement was the so-called Zimmermann telegram. British intelligence intercepted and decoded a top-secret telegram from German foreign minister Arthur Zimmermann to the German ambassador to Mexico, instructing the latter to invite Mexico to join the war effort on the German side, should the United States declare war on Germany. It further went on to encourage Mexico to invade the United States if such a declaration came to pass. Mexico’s invasion would create a diversion and permit Germany a clear path to victory. In exchange, Zimmermann offered to return to Mexico land that was previously lost to the United States in the Mexican-American War.

The likelihood that Mexico, weakened by its own revolution and civil war, could wage war against the United States was remote at best. But combined with Germany’s unrestricted submarine warfare and the sinking of American ships, the Zimmermann telegram made a powerful argument for a declaration of war. The outbreak of the Russian Revolution in February raised the prospect of democracy in the Eurasian empire and removed an important moral objection to entering the war on the side of the Allies.

On April 2, 1917, Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany. Congress debated for four days, and several senators and congressmen expressed their concerns that the war was being fought over U.S. economic interests more than strategic need or democratic ideals. When Congress voted on April 6, 56 voted against the resolution, including the first woman ever elected to Congress, Representative Jeannette Rankin. This was the largest “no” vote against a war resolution in American history.

Winning the War

When the United States declared war on Germany, the Allied forces were close to exhaustion. Great Britain faced near-certain defeat and requested immediate troop reinforcements to boost Allied spirits and help crush German fighting morale, which was already weakened by short supplies on the frontlines and hunger on the home front. Wilson agreed, immediately sending 200,000 American troops in June 1917. These soldiers were placed in “quiet zones” while they trained and prepared for combat.

It would not be until May 1918, that Americans were fully engaged in the war. Battles that summer turned the tide of the war. By November 11, 1918, Germany and the Allies declared an immediate armistice. Compared to the incredible carnage endured by Europe, the United States’ battles were brief and successful, although the appalling fighting conditions and significant casualties made it feel otherwise to Americans, both at war and at home.

Attribution:

OpenStax, U.S. History. OpenStax CNX. Jul 27, 2017 http://cnx.org/contents/a7ba2fb8-8925-4987-b182-5f4429d48daa@3.84.

World War I and the United States

Watch from beginning through 13:42.

Attribution:

Saylor Academy. (May 12, 2011). World War One and the United States. [Saylor Academy] Retrieved August 5, 2017 from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PmiC5B-8ebQ

Zimmermann Telegram

Attribution:

Zimmermann Telegram, 1917; Decimal File, 1910-1929, 862.20212/82A and Decoded Zimmermann Telegram, 1917; Decimal File, 1910-1929, 862.20212/69, General Records of the Department of State; Record Group 59; National Archives.

Summary

President Woodrow Wilson came into office in 1913 trying to reverse the course of the country’s foreign policy of the first decade of the 20th century. Rejecting Roosevelt’s aggressive interventionism in Latin America, Wilson aimed to promote intervention only when it was a moral imperative to do so. However, global politics worked against Wilson as war broke out it Europe. Although America did not officially join the war effort until 1917, the United States was not completely neutral. Trade with the Allies quadrupled while trade with Germany shrank. Economically, the United States had sided with Great Britain and France. After indirect aggression from Germany in the form of U-Boat attacks and the Zimmerman telegram, the United States officially joined the war in 1917 on the side of the Allies.

American entered the 1910s reluctant to entangle themselves in European affairs. Diplomatically, the United States wished to remain separate from Europe as had been the tradition laid out in the Monroe Doctrine. However, the economic reality of a growing industrial economy meant that the United States interests were not isolated from those of Europe. World War I drew the United States into conflicts beyond the Western Hemisphere. At the end of World War I, it had become clear that the United States could not remain isolated within the Western Hemisphere. But the death and financial toll the war had taken on the United States left many wanting to return to a policy of isolation.