36

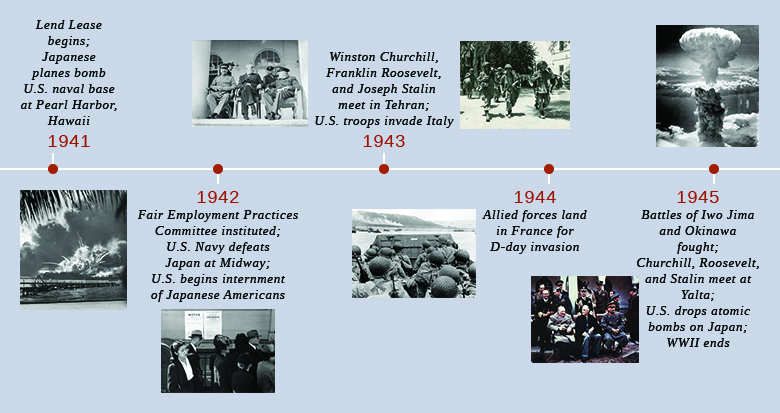

World War II launched the United States on a path of military and diplomatic strength abroad and economic rebuilding followed by prosperity at home. While during the 1920s and 1930s there were Americans who favored active engagement in Europe, most Americans, including many prominent politicians, were leery of getting too involved in European affairs or accepting commitments to other nations that might restrict America’s ability to act independently, keeping with the isolationist tradition. Although the United States continued to intervene in the affairs of countries in the Western Hemisphere during this period, the general mood in America was to avoid becoming involved in any crises that might lead the nation into another global conflict. However, the Great Depression that had plagued the United States in the 1930s was part of a larger global economic depression. In Europe, this economic depression and the smoldering tensions left over from the Great War led to the rise of powerful dictators in countries like Germany and Italy. As these countries became aggressively expansionist, Europe again found itself at war. The outbreak of World War II forced the United States to involve itself once again in European affairs.

Like Wilson before him, Franklin Delano Roosevelt also articulated his vision for a peaceful world before the United States entered the war in December of 1941 following the attack on Pearl Harbor. FDR’s Four Freedoms (freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear) came to define postwar American Democracy. But when FDR introduced these four essential human freedoms, he applied them to all nations. Although FDR did not live to see the end of the war, his vision for global freedom is reflected in the peace agreements that ended the war. And this vision of American Democracy set the stage for the growth of American power and influence abroad in the decades following the war.

World War II

Neutrality in the Face of War

President Franklin Roosevelt was aware of the challenges facing the targets of Nazi aggression in Europe and Japanese aggression in Asia. Although he hoped to offer U.S. support, Congress’s commitment to nonintervention was difficult to overcome. Some believed that the United States had been tricked into participating in World War I by a group of industrialists and bankers who sought to gain from the country’s participation in the war.

To ensure that the United States did not get drawn into another war, Congress passed a series of Neutrality Acts in the second half of the 1930s. The Neutrality Act of 1935 banned the sale of armaments to warring nations. The following year, another Neutrality Act prohibited loaning money to belligerent countries. Then, the Neutrality Act of 1937, forbade the transportation of weapons or passengers to belligerent nations on board American ships and also prohibited American citizens from traveling on board the ships of nations at war.

When war began between Japan and China in 1937, Roosevelt sought ways to help the Chinese that did not violate U.S. law. Since Japan did not formally declare war on China, a state of belligerency did not technically exist. So, in 1940, the US sent one hundred P-40 fighter planes to China and allowed American volunteers, who technically became members of the Chinese Air Force, to fly them.

On September 1, 1939, Hitler invaded Poland. Britain and France had already knew that Hitler could not be trusted and that his territorial demands were insatiable. On September 3, 1939, they declared war on Germany, and the European phase of World War II began. Responding to the German invasion of Poland, Roosevelt worked with Congress to alter the Neutrality Laws to permit a policy of “Cash and Carry” of munitions for Britain and France. The legislation, passed November 1939, permitted belligerents to purchase war materiel if they could pay cash and arrange for transportation on board their own ships.

In the spring of 1940, the Germans defeated France in six weeks. The Battle of Britain began, as Germany tried to bomb England into submission. Roosevelt became increasingly concerned over England’s ability to hold out against the bombings. In June 1941, Hitler broke the nonaggression pact with the Soviet Union and marched his armies deep into Soviet territory. But the Soviets were eventually able to defeat Germany at the Battle of Stalingrad, from August 23, 1942 until February 2, 1943.

In March 1941, concerns over Britain’s ability to defend itself also influenced Congress to authorize a policy of “Lend Lease”, the United States could sell, lease, or transfer armaments to any nation deemed important to the defense of the United States. Lend Lease effectively ended the policy of nonintervention and dissolved America’s pretense of being a neutral nation.

The US is Drawn into War: Pearl Harbor

At 7:48 a.m. on Sunday, December 7, the Japanese attacked the U.S. Pacific fleet at anchor in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Whatever reluctance to engage in conflict the American people had before December 7, 1941 quickly evaporated. President Roosevelt, referring to the day of the attack as “a date which will live in infamy,” asked Congress for a declaration of war, which it delivered to Japan on December 8. On December 11, Germany and Italy declared war on the United States in accordance with their alliance with Japan.

Wartime Diplomacy

In August 1941, Roosevelt had met with the British prime minister, Winston Churchill, off the coast of Newfoundland, Canada. At this meeting, the two leaders drafted the Atlantic Charter, the blueprint of Anglo-American cooperation during World War II. The charter stated:

- The United States and Britain sought no territory from the conflict.

- Citizens of all countries should be given the right of self-determination,

- Self-government should be restored in places where it had been eliminated

- Trade barriers should be lowered.

And called for:

- freedom of the seas

- postwar disarmament

And renounced the use of force to settle international disputes.

Despite the Japanese attack, Roosevelt was more concerned about Great Britain. Roosevelt viewed Germany as the greater threat to freedom. Hence, a “Europe First” strategy. That meant the United States would concentrate the majority of its resources and energies in achieving a victory over Germany first and then focus on defeating Japan. Churchill and Roosevelt were committed to saving Britain and acted with this goal in mind, often ignoring the needs of the Soviet Union, in part because, in keeping with the Atlantic Charter, Roosevelt imagined an “empire-free” postwar world.

Roosevelt entered World War II with a vision of the United States as the preeminent world power economically, politically and militarily. A world where the United States would succeed Britain as the leader of Western capitalist democracies, replacing the old British imperial system with one based on free trade and decolonization.

Through a series of wartime conferences, Roosevelt and the other global leaders sought a strategy to both defeat the Germans and bolster relationships among allies. In January 1943, at Casablanca, Morocco, Churchill convinced Roosevelt to delay an invasion of France in favor of an invasion of Sicily. It was also at this conference that Roosevelt enunciated the doctrine of “unconditional surrender.” Roosevelt agreed to demand an unconditional surrender from Germany and Japan to assure the Soviet Union that the United States would not negotiate a separate peace and prepare the former belligerents for a thorough and permanent transformation after the war. Roosevelt thought that announcing this as a specific war aim would discourage any nation or leader from seeking any negotiated armistice that would hinder efforts to reform and transform the defeated nations. Stalin affirmed the concept of unconditional surrender. However, he was dismayed over the delay in establishing a “second front” in western Europe, which Stalin had been demanding since 1941, offered the best means of drawing Germany away from the east. At a meeting in Tehran, Iran, in November 1943, Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin met to finalize plans for a cross-channel invasion.

Yalta and Preparing for Victory

The last time the Big Three met was in February 1945 at Yalta in the Soviet Union. Roosevelt was sick, and Stalin’s armies were pushing the German army back towards Berlin. Churchill and Roosevelt thus had to accept a number of compromises that strengthened Stalin’s position in eastern Europe. They agreed to allow the Communist government installed by the Soviet Union in Poland to remain in power until free elections took place. For his part, Stalin reaffirmed his commitment to enter the war against Japan following the surrender of Germany. He also agreed that the Soviet Union would participate in the United Nations, a new peacekeeping body intended to replace the League of Nations. The Big Three left Yalta with many details remaining unclear, particularly plans for the treatment of Germany and the shape of postwar Europe.

By April 1945, Soviet forces had reached Berlin, and both the U.S. and British Allies were pushing up against Germany’s last defenses in the western. Hitler committed suicide on April 30, 1945. On May 8, Germany surrendered. The war in Europe was over.

The victorious Allies set about determining how to rebuild Europe at the Potsdam Summit Conference in July 1945. Attending the conference were Stalin, Truman (who became President after Roosevelt died), and Churchill, the outgoing prime minister, and the new British prime minister, Clement Attlee. Germany and Austria, and their capital cities, would be divided into four zones—to be occupied by the British, French, Americans, and Soviets. In addition, the Allies agreed to dismantle Germany’s heavy industry in order to make it impossible for the country to produce more armaments.

The War Ends: Dropping the Atomic Bomb

All belligerents in World War II sought to develop powerful and devastating weaponry. As early as 1939, German scientists had discovered how to split uranium atoms, the technology that would ultimately allow for the creation of the atomic bomb. Albert Einstein, who had emigrated to the United States in 1933 to escape the Nazis, urged President Roosevelt to launch an American atomic research project, and Roosevelt agreed to do so, with reservations. In late 1941, the program received its code name: the Manhattan Project. Located at Los Alamos, New Mexico, the Manhattan Project ultimately employed 150,000 people and cost some $2 billion. In July 1945, the project’s scientists successfully tested the first atomic bomb.

The US dropped the first Atomic bomb on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. Approximately seventy thousand people died in the original blast. The same number would later die of radiation poisoning. When Japan refused to surrender, a second atomic bomb, was dropped on Nagasaki on August 9. At least sixty thousand people were killed at Nagasaki.

The bombs had the desired effect of getting Japan to surrender. Even before the atomic attacks, the conventional bombings of Japan, the defeat of its forces in the field, and the entry of the Soviet Union into the war had convinced the Imperial Council that they had to end the war. They had hoped to negotiate the terms of the peace, but Emperor Hirohito intervened after the destruction of Nagasaki and accepted unconditional surrender. Although many Japanese shuddered at the humiliation of defeat, most were relieved that the war was over. Japan’s industries and cities had been thoroughly destroyed.

The victors had yet another nation to rebuild and reform, but the war was finally over. Following the surrender, the Japanese colony of Korea was divided along the thirty-eighth parallel; the Soviet Union was given control of the northern half and the United States was given control of the southern portion. In October 1945, the United Nations was created. People around the world celebrated the end of the conflict.

Attribution:

OpenStax, U.S. History. OpenStax CNX. Jul 27, 2017 http://cnx.org/contents/a7ba2fb8-8925-4987-b182-5f4429d48daa@3.84.

The Atlantic Charter (1941)

The leaders of the United States and United Kingdom signed the Atlantic Charter in August 1941. The short document neatly outlined an idealized vision for political and economic order of the postwar world.

AUGUST 14, 1941

The President of the United States of America and the Prime Minister, Mr. Churchill, representing His Majesty’s Government in the United Kingdom, being met together, deem it right to make known certain common principles in the national policies of their respective countries on which they base their hopes for a better future for the world.

First, their countries seek no aggrandizement, territorial or other;

Second, they desire to see no territorial changes that do not accord with the freely expressed wishes of the peoples concerned;

Third, they respect the right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live; and they wish to see sovereign rights and self-government restored to those who have been forcibly deprived of them;

Fourth, they will endeavor, with due respect for their existing obligations, to further the enjoyment by all States, great or small, victor or vanquished, of access, on equal terms, to the trade and to the raw materials of the world which are needed for their economic prosperity;

Fifth, they desire to bring about the fullest collaboration between all nations in the economic field with the object of securing, for all, improved labor standards, economic advancement and social security;

Sixth, after the final destruction of the Nazi tyranny, they hope to see established a peace which will afford to all nations the means of dwelling in safety within their own boundaries, and which will afford assurance that all the men in all lands may live out their lives in freedom from fear and want;

Seventh, such a peace should enable all men to traverse the high seas and oceans without hindrance;

Eighth, they believe that all of the nations of the world, for realistic as well as spiritual reasons must come to the abandonment of the use of force. Since no future peace can be maintained if land, sea or air armaments continue to be employed by nations which threaten, or may threaten, aggression outside of their frontiers, they believe, pending the establishment of a wider and permanent system of general security, that the disarmament of such nations is essential. They will likewise aid and encourage all other practicable measure which will lighten for peace-loving peoples the crushing burden of armaments.

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Winston S. Churchill

[Available online via The Avalan Project, http://avalon.law.yale.edu/wwii/atlantic.asp.]

Attribution:

Atlantic Charter (August 14, 1941). Retrieved from http://www.americanyawp.com/reader/24-world-war-ii/937-2/

The Attack on Pearl Harbor

Attribution:

Department of Defense. (December 6, 2016). Everything You should Know About the Attack on Pearl Harbor in 120 Seconds. [Video File]. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FLG-LTrlsFM

Summary

America sought, at the end of the First World War, to create new international relationships that would make such wars impossible in the future. But as the Great Depression hit Europe, several new leaders rose to power under the new political ideologies of Fascism and Nazism. Mussolini in Italy and Hitler in Germany were both proponents of Fascism, using dictatorial rule to achieve national unity. Still, the United States remained focused on the economic challenges of its own Great Depression. Hence, there was little interest in getting involved in Europe’s problems or even the China-Japan conflict. It soon became clear that Germany and Italy’s alliance was putting democratic countries at risk. Then when Japan, an ally of Germany and Italy, attacked Pearl Harbor, America’s feelings toward war shifted, and the country was quickly pulled into the global conflict.

But from the outset, as demonstrated by the Atlantic Charter, FDR sought to lay the foundation for a peaceful postwar world in which the United States would play a major and permanent role. Appeasement and nonintervention had been proven to be shortsighted and tragic policies that failed to provide security and peace either for the United States or for the world. So after the Germans surrendered in May of 1945 and the Japanese surrendered in August of 1945, officially ending the second World War, the United States looked to create a peaceful world centered on democracy and free trade.