6

Awareness of the environmental consequences of industrialization, urbanization, pollution, and overhunting did not begin to emerge on a broad scale in the United States until the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Since the colonial era, Americans had been treating the environment of North America as an infinite resource, and conservation, if considered at all, was largely viewed as a pointless endeavor. The continental United States was so large, and the native flora and fauna so vast, that conservation simply did not appear necessary.

As early as 1854, others, such as Henry David Thoreau, lamented the lost landscape of North America, citing the extinction of numerous animals and widespread deforestation as evidence that the nation’s environment was being irreversibly altered. It was not until the late 19th century, however, that the consequences of America’s environmental practices produced a sea change in environmental consciousness and activism. Two major schools of thought in environmental policy and activism had emerged by the end of the 19th century – preservation and conservation. Preservationists advocated keeping uninhabited, pristine lands in their native state. Conservationists, on the other hand, advocated land management and the efficient use of the environment in order to best fit the economic and political needs of the country.

By the Progressive Era, battles over environmental policy were being waged in the highest offices of American government, which would shape how the nation approached the environment and wildlife for the next century. Do you identify as an environmentalist? And how has the environment impacted your experience of the United States?

Progressive Environmentalism

The potential scope of environmental destruction wrought by industrial capitalism was unparalleled in human history. Professional bison hunting expeditions nearly eradicated an entire species, industrialized logging companies could denude whole forests, chemical plants could pollute an entire region’s water supply. As Americans built up the West and industrialization marched ever onward, reformers embraced environmental protections.

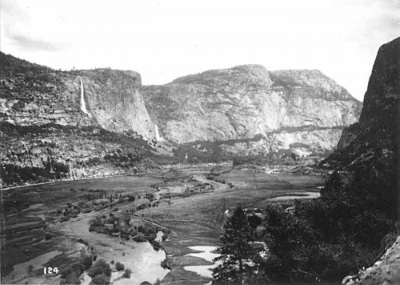

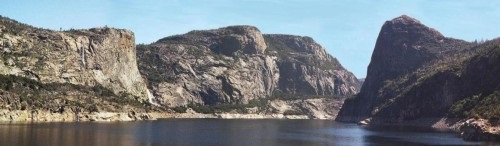

Historians often cite preservation and conservation as the two competing strategies that dueled for supremacy among environmental reformers during the Progressive Era. The tensions between these two approaches crystalized in the debate over a proposed dam in the Hetch Hetchy Valley in California. The fight revolved around the provision of water for San Francisco. Engineers identified the location where the Tuolomne River ran through Hetch Hetchy as an ideal site for a reservoir. The project had been suggested in the 1880s but picked up momentum in the early twentieth century. But the valley was located inside Yosemite National Park. (Yosemite was designated a national park in 1890, though the land had been set aside earlier in a grant approved by President Lincoln in 1864.) The debate over Hetch Hetchy revealed two distinct positions on the value of the valley and on the purpose of public lands.

John Muir, a naturalist, writer, and founder of the Sierra Club, invoked the “God of the Mountains” in his defense of the valley in its supposedly pristine condition. Gifford Pinchot, arguably the father of American forestry and a key player in the federal management of national forests, meanwhile emphasized what he understood to be the purpose of conservation: “to take every part of the land and its resources and put it to that use in which it will serve the most people.”Muir took a wider view of what the people needed, writing that “everybody needs beauty as well as bread.” These dueling arguments revealed the key differences in environmental thought: Muir, on the side of the preservationists, advocated setting aside pristine lands for their aesthetic and spiritual value, for those who could take his advice to “[get] in touch with the nerves of Mother Earth.” Pinchot, on the other hand, led the charge for conservation, a kind of environmental utilitarianism that emphasized the efficient use of available resources, through planning and control and “the prevention of waste.” In Hetch Hetchy, conservation won out. Congress approved the project in 1913. The dam was built and the valley flooded for the benefit of San Francisco residents.

The image on the top shows the Hetch Hetchy Valley before it was dammed. The bottom photograph, taken almost a century later, shows the obvious difference after damming, with the submergence of the valley floor under the reservoir waters. Photograph of the Hetch Hetchy Valley before damming, from the Sierra Club Bulletin, January 1908. Wikimedia; Daniel Mayer (photographer), May 2002. Wikimedia.

While preservation was often articulated as an escape from an increasingly urbanized and industrialized way of life and as a welcome respite from the challenges of modernity (at least, for those who had the means to escape), the conservationists were more closely aligned with broader trends in American society. Although the “greatest good for the greatest number” was very nearly the catch phrase of conservation, conservationist policies most often benefited the nation’s financial interests. For example, many states instituted game laws to regulate hunting and protect wildlife, but laws could be entirely unbalanced. In Pennsylvania, local game laws included requiring firearm permits for non-citizens, barred hunting on Sundays, and banned the shooting of songbirds. These laws disproportionately affected Italian immigrants, critics said, as Italians often hunted songbirds for subsistence, worked in mines for low wages every day but Sunday, and were too poor to purchase permits or to pay the fines levied against them when game wardens caught them breaking these new laws. Other laws, for example, offered up resources to businesses at costs prohibitive to all but the wealthiest companies and individuals, or with regulatory requirements that could be met only by companies with extensive resources.

But it Progressive Era environmentalism was about more than the management of American public lands. After all, reformers addressing issues facing the urban poor were doing environmental work. Settlement house workers like Jane Addams and Florence Kelley focused on questions of health and sanitation, while activists concerned with working conditions, most notably Dr. Alice Hamilton, investigated both worksite hazards and occupational and bodily harm. The progressives’ commitment to the provision of public services at the municipal level meant more coordination and oversight in matters of public health, waste management, even playgrounds and city parks. Their work focused on the intersection of communities and their material environments, highlighting the urgency of urban environmental concerns.

While reform movements focused their attention on the urban poor, other efforts targeted rural communities. The Country Life movement, spearheaded by Liberty Hyde Bailey, sought to support agrarian families and encourage young people to stay in their communities and run family farms. Early-twentieth-century educational reforms included a commitment to environmentalism at the elementary level. Led by Bailey and Anna Botsford Comstock, the nature study movement took students outside to experience natural processes and to help them develop observational skills and an appreciation for the natural world.

Other examples highlight the interconnectedness of urban and rural communities in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The extinction of the North American passenger pigeon reveals the complexity of Progressive Era relationships between people and nature. Passenger pigeons were actively hunted, prepared at New York’s finest restaurants and in the humblest of farm kitchens. Some hunted them for pay; others shot them in competitions at sporting clubs. And then they were gone, their ubiquity giving way only to nostalgia. Many Americans took notice at the great extinction of a species that had perhaps numbered in the billions and then was eradicated. Women in Audubon Society chapters organized against the fashion of wearing feathers—even whole birds—on ladies’ hats. Upper and middle-class women made up the lion’s share of the membership of these societies. They used their social standing to fight for birds. Pressure created national wildlife refuges and key laws and regulations that included the Lacey Act of 1900, banning the shipment of species killed illegally across state lines. Following the feathers backward, from the hats to the hunters to the birds themselves, and examining the ways women mobilized contemporary notions of womanhood in the service of protecting avian beauty, reveals a tangle of cultural and economic processes. Such examples also reveal the range of ideas, policies, and practices wrapped up in figuring out what—and who—American nature should be for.

Attribution:

Baker, Andrew C et al. The Progressive Era. (n.d.). In The American Yawp. Retrieved September 9, 2017, from http://www.americanyawp.com/text/20-the-progressive-era/

Beyond the Civil Rights

At the same time that many Americans were fighting for greater equality, the environmental movement experienced a resurgence. After years of industrialization, urbanization, and, more recently, suburbanization, more and more Americans began to focus on their effects on the environment.

American environmentalism’s significant gains during the 1960s emerged in part from Americans’ recreational use of nature. Postwar Americans backpacked, went to the beach, fished, and joined birding organizations in greater numbers than ever before. These experiences, along with increased formal education, made Americans more aware of threats to the environment and, consequently, to themselves. Many of these threats increased in the post-war years as developers bulldozed open space for suburbs and new hazards from industrial and nuclear pollutants loomed.

By the time that biologist Rachel Carson published her landmark book, Silent Spring, in 1962, a nascent environmentalism had emerged in America. Silent Spring stood out as an unparalleled argument for the interconnectedness of ecological and human health. Pesticides, Carson argued, also posed a threat to human health, and their overuse threatened the ecosystems that supported food production. Carson’s argument was compelling to many Americans, including President Kennedy, and was virulently opposed by chemical industries that suggested the book was the product of an emotional woman, not a scientist.

After Silent Spring, the social and intellectual currents of environmentalism continued to expand rapidly, culminating in the largest demonstration in history, Earth Day, on April 22, 1970, and in a decade of lawmaking that significantly restructured American government. Even before the massive gathering for Earth Day, lawmakers from the local to federal level had pushed for and achieved regulations to clean up the air and water. President Richard Nixon signed the National Environmental Policy Act into law in 1970, requiring environmental impact statements for any project directed or funded by the federal government. He also created the Environmental Protection Agency, the first agency charged with studying, regulating, and disseminating knowledge about the environment. A raft of laws followed that were designed to offer increased protection for air, water, endangered species, and natural areas.

Today Americans continue to debate what are often seen as competing economic and environmental interests. Reaching consensus on tackling issues like climate change through regulation and legislation has been difficult, particularly at the federal level. As a result, different states and municipalities have begun to pursue a variety of policies to limit greenhouse gas emissions, promote renewable energy, and promote public transportation initiatives. Many of these changes are the result of grassroots activism and pressure by environmental advocacy groups.

Whether the United States joins other nations in multilateral agreements and treaties to tackle global challenges like climate change remains to be seen.

Attribution:

Samuel Abramson et al. The Sixties. In The American Yawp. Last modified August 1, 2016. Retrieved from http://www.americanyawp.com/text/27-the-sixties/#VII_Beyond_Civil_Rights. With adjustments by James Denby.

Summary

Commenting on the nation’s environmental heritage, President Theodore Roosevelt emphasized the importance of sound environmental policy in the early 19th century, asserting in a speech to Congress, “Here is your country. Cherish these natural wonders, cherish the natural resources, cherish the history and romance as a sacred heritage, for your children and your children’s children. Do not let selfish men or greedy interests skin your country of its beauty, it riches or its romance.” Although many Americans agreed wholeheartedly with Roosevelt’s message, throughout the 20th century numerous other forces in American life worked at odds with Roosevelt’s mission to protect the nation’s natural resources for future generations.

The 1960s and 1970s represented the culmination of nearly a century of environmental activism, and new policies and regulations were designed to prohibit pollution and protect American air, water, endangered species, and land. Although many of these policies have been responsible for a markedly cleaner environment, and represent an important environmental heritage, Americans have also inherited the consequences of centuries of pollution and environmental malpractice. The contemporary debate over climate change in the United States highlight the fact that Americans cannot escape their environmental past, and that debates over the environment remain a prominent feature of American politics.

Today the environmental movement in the United States is confronting global challenges like climate change. With the federal government hampered by fractious debate over the economic costs of policy changes, environmentalists have focused on policy changes at the state and local level.