29

Coming to office in the midst of the Great Depression, Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) promised the American people a New Deal. It had become clear by 1932 that the laissez-faire approach to government regulation and the reliance on volunteerism to help the expanding number of poor and needy Americans were not sufficient to maintain economic stability nationally or individually. Through his New Deal programs, FDR transformed the government’s relationship to the economy and to the American people. Through regulation enacted under the New Deal, the government took a greater hand in the operation of American business. Through social welfare programs, the government also took a greater hand in average Americans’ everyday economies. The New Deal brought new meaning to an American standard of living and economic security.

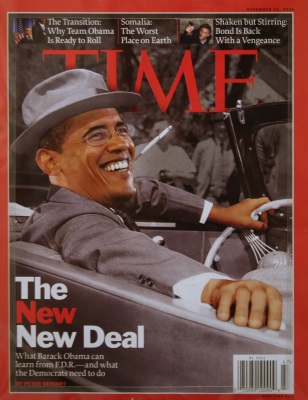

The legacy of the New Deal can be seen throughout the economic policies of the Presidents who have succeeded FDR. From Great Society to the Affordable Care Act, efforts to expand American economic security have continued. But the tensions over the role of the federal government in the daily economies of Americans have also continued. In the 1930s, there was push back against the New Deal among those who believed that the Democrat, FDR, had gone too far. Republican opposition to federal welfare has continued up into our present day. However, one truth remains, the federal government would never again be brought back to its pre-New Deal size.

Changing Economic Policies

FDR and the First New Deal

On July 1, 1932, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the Democratic Party presidential nominee, delivered one of the most famous acceptance speeches in American history. He promised, “I pledge you, I pledge myself, to a new deal for the American people.” Newspaper editors seized upon the phrase “new deal,” and it entered the American political lexicon as shorthand for Roosevelt’s program to address the Great Depression. He spent the months between his election and inauguration traveling, planning, and assembling a team of advisors, the famous “Brain Trust” of academics and experts, to help him formulate a plan of attack.

In his first days in office, Roosevelt and his advisers prepared, submitted, and secured Congressional enactment of numerous laws designed to arrest the worst of the Great Depression with the help of the federal government.

Roosevelt immediately looked to stabilize the collapsing banking system.

- He declared a national “bank holiday” closing American banks

- Passed the Emergency Banking Act

- Passed the Glass-Steagall Banking Act, which instituted federal deposit insurance and barred the mixing of commercial and investment banking.

Stabilizing the banks was only a first step. In the remainder of his “First Hundred Days,” Roosevelt and his congressional allies focused on programs for suffering Americans. Americans and their congressional representatives conceded that the crisis demanded swift and immediate action.

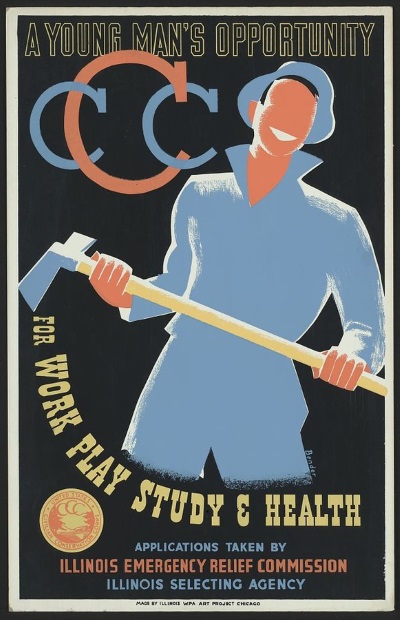

– Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) employed young men on conservation and reforestation projects

– Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) provided direct cash assistance to state relief agencies

– The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) built a series of hydroelectric dams along the Tennessee River to bring power and economic development to a chronically depressed region

The heart of Roosevelt’s early recovery program consisted of two massive efforts to stabilize and coordinate the American economy:

- the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA) aimed to raise the prices of agricultural commodities by offering cash incentives to voluntarily limit farm production

- the National Recovery Administration (NRA) suspended antitrust laws to allow businesses to establish “codes” that would coordinate prices, regulate production levels, and establish conditions of employment to curtail “cutthroat competition.”

In exchange for these exemptions, businesses agreed to provide reasonable wages and hours, end child labor, and allow workers the right to unionize. Participating businesses could display a placard with the NRA’s “Blue Eagle,” showing their cooperation in efforts to combat the Great Depression.

GDP climbed once more, but even as output increased, unemployment remained stubbornly high. If the economy could not put people back to work, the New Deal would try:

– The Civil Works Administration (CWA)

– The Works Progress Administration (WPA)

These put unemployed men and women to work on projects designed and proposed by local governments.

- The Public Works Administration (PWA) provided grants-in-aid to local governments for infrastructure projects, such as bridges, tunnels, schoolhouses, libraries, and America’s first federal public housing projects.

Together, they provided not only tangible projects of immense public good but employment for millions.

Voices of Protest

Despite the unprecedented actions taken in his first year in office, Roosevelt’s New Deal demonstrated a reluctance to radically tinker with the nation’s foundational economic and social structures. Many high-profile critics attacked Roosevelt for not going far enough, and, beginning in 1934, Roosevelt and his advisors were forced to respond.

Senator Huey Long, a flamboyant Democrat from Louisiana, was perhaps the most important “voice of protest.” Long proposed a “Share Our Wealth” program in which the federal government would confiscate the assets of the extremely wealthy and redistribute them to the less well-off through guaranteed minimum incomes. Over 27,000 “Share the Wealth” clubs sprang up across the nation. Long envisioned the movement as a stepping stone to the presidency, but his crusade ended in late 1935 when he was assassinated on the floor of the Louisiana state capitol.

Francis Townsend, a former doctor and public health official from California, promoted a plan for old age pensions which, he argued, would provide economic security for the elderly (who disproportionately suffered poverty) and encourage recovery by allowing older workers to retire from the work force.

If many Americans urged Roosevelt to go further in addressing the economic crisis, the president faced even greater opposition from conservative politicians and business leaders. Yet the greatest opposition came from the Supreme Court, a conservative court filled with appointments made from the long years of Republican presidents.

By early 1935 the Court was reviewing programs of the New Deal. On May 27, a day Roosevelt’s supporters called “Black Monday,” the justices unanimously declared the NRA unconstitutional, because they found that both the AAA and the NIRA overreached federal authority by getting involved in intra-state trade.

The Second New Deal

Facing reelection and rising opposition from both the left and the right, Roosevelt decided to act. In 1935, hoping to reconstitute some of the protections afforded workers in the now-defunct NRA, Roosevelt got the National Labor Relations Act (known as the Wagner Act) passed, offering federal legal protection, for the first time, for workers to organize unions. Then Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act, creating the modern minimum wage. The Second New Deal also:

- Restored the federal income tax

- Mandated new reporting requirements for publicly traded companies

- Refinanced long-term home mortgages for struggling homeowners

- Attempted rural reconstruction projects to bring farm incomes in line with urban ones.

The signature piece of Roosevelt’s Second New Deal was the Social Security Act, which provided for old-age pensions, unemployment insurance, and economic aid to assist both the elderly and dependent children. In the American context this was a revolutionary concept. He specifically insisted that social security be financed from payroll, not the federal government; “No dole,” Roosevelt said repeatedly. He thereby helped separate Social Security from the stigma of being an undeserved “welfare” entitlement. Social Security became the centerpiece of the modern American social welfare state. It was the culmination of a long progressive push for government-sponsored social welfare, an answer to the calls of Roosevelt’s opponents on the Left for reform, a response to the intractable poverty among America’s neediest groups, and a recognition that the government would now assume some responsibility for the economic well-being of its citizens. But for all of its groundbreaking provisions, the Act, and the larger New Deal as well, excluded large swaths of the American population, including African Americans who worked in jobs excluded from Social Security benefits, such as domestic labor.

LBJ & The Great Society

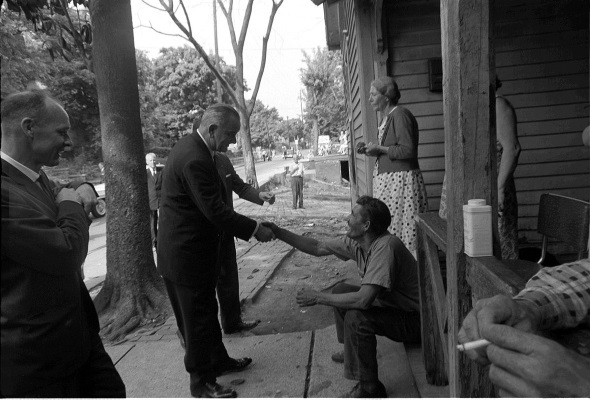

Lyndon B. Johnson was both ruthlessly ambitious and keenly conscious of poverty and injustice. He idolized Franklin Roosevelt whose New Deal had brought improvements for the impoverished Central Texas where Johnson grew up.

While his first actions as President dealt with ensuring the passage of Civil Rights legislation, Johnson soon turned to the question of economic inequality. In 1964, Johnson laid out a sweeping vision of domestic reforms known as the Great Society. Johnson called for “an end to poverty and racial injustice” and challenged the American people to “enrich and elevate our national life, and to advance the quality of our American civilization.” At its heart, he promised, the Great Society would uplift racially and economically disenfranchised Americans, too long denied access to federal guarantees of equal democratic and economic opportunity, while simultaneously raising all Americans’ standards and quality of life.

The Great Society’s legislation was breathtaking in scope, and many of its programs and agencies are still with us today. Most importantly, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 codified federal support for many of the civil rights movement’s goals by prohibiting job discrimination, abolishing the segregation of public accommodations, and providing vigorous federal oversight of southern states’ primary and general election laws in order to guarantee minority access to the ballot.

In addition to civil rights, the Great Society took on a range of quality of life concerns.

- Federal Food Stamp Program sought to end hunger.

- Medicare and Medicaid would ensure access to quality medical care for the aged and poor.

- Elementary and Secondary Education Act sustained federal investment in public education, totaling more than $1 billion.

- The National Endowment for the Arts and The National Endowment for the Humanities, invested in arts and letters and funds American cultural expression to this day.

The national conversation largely focused on the $3 billion spent on War on Poverty programming such as the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964. No EOA program was more controversial than Community Action, considered the cornerstone antipoverty program. Johnson’s antipoverty planners felt the key to uplifting disenfranchised and impoverished Americans was involving poor and marginalized citizens in the actual administration of poverty programs. Community Action Programs would give disenfranchised Americans a role in planning federally funded programs meant to benefit them. Community Action sought to build grassroots civil rights and community advocacy organizations.

Despite widespread support for most Great Society programs, the War on Poverty became the focal point of domestic criticisms from the left and right. On the left, frustrated liberals recognized the president’s resistance to empowering minority poor and also assailed the growing war in Vietnam, the cost of which undercut domestic poverty spending. As racial unrest and violence swept across urban centers in the late 1960s, critics from the right lambasted federal spending for “unworthy” and even criminal citizens.

Despite the fact that these programs provoked conservative resistance subsequent presidents and Congresses have left largely intact the bulk of the Great Society.

Wright, Ben and Joseph Locke, Eds.(2017). The American Yawp. Retrieved from http://www.americanyawp.com/index.html

With adjustments by Margaret Carmack.

Extension: An NRA commercial that calls on Americans to support the New Deal and to help give jobs to Americans. Demonstrates how FDR and was trying to sell the New Deal to the American people.

Khalbrae (June 27, 2015) National Recovery Administration (NRA) Promo. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lK8GMJm0D0A

Extension: This is FDR’s vision of the economy. Explains the impact of the New Deal

Franklin D. Roosevelt, “Second Inaugural Address,” January 20, 1937. Available online via Avalon Project (http://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/froos2.asp).

Extension: More in-depth explanations of LBJ’s Great Society

Josh Haynes (March 18, 2017). LBJ’s Great Society. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X8zxFU-CCRI

Summary

Before World War I, the American national state, though powerful, had been a “government out of sight.” After the New Deal, Americans came to see the federal government as a potential ally in their daily struggles. The programs put in place by FDR and his New Deal helped Americans to find work, secure a decent wage, get a fair price for agricultural products, and organize a union. Together with other programs, such as the Social Security Act, the New Deal worked to create a standard of living for Americans.

The so called “New Deal order,” a constellation of “ideas, public policies, and political alliances,” though changing, has continued to guided American politics from Roosevelt’s Hundred Days forward to today’s debates over health care mandates.. Access to programs put in place by FDR and then Johnson have come to be seen as fundamental rights of citizenship. Even as conservatives have, over the decades, worked to dismantle some of these programs, the role of the federal government in American’s everyday economies has never been reduced to pre-New Deal levels.

Indeed, the New Deal’s legacy still remains. Some have pointed to the more modern implementation of the Affordable Healthcare Act, which mandates quality health care be available to all Americans, as another step towards building the American welfare state. And as we have seen recently, the battle lines over the role of the federal government in American’s everyday economies stills shapes American politics.