24

Following the passage of the 13th amendment, southern states instituted Black Codes, or laws aimed at limiting the new freedoms of emancipated slaves. These Black Codes laid the foundation for a later system of laws and customs known as Jim Crow laws. Under the guise of “separate but equal,” Jim Crow laws made it legal to segregate education and public facilities.

In reality, separate rarely meant equal. This physical separation of races was meant to protect white culture and white superiority in the South. The legal and forced separation included restaurants, public transportation, schools, water fountains, movie theatres, sporting facilities, etc. In the mid-1950s one of the first mass movements against racial segregation was organized in the form of the Montgomery Bus Boycott. This boycott kicked off a larger movement of sit-ins and other demonstrations aimed at desegregating public transportation and facilities.

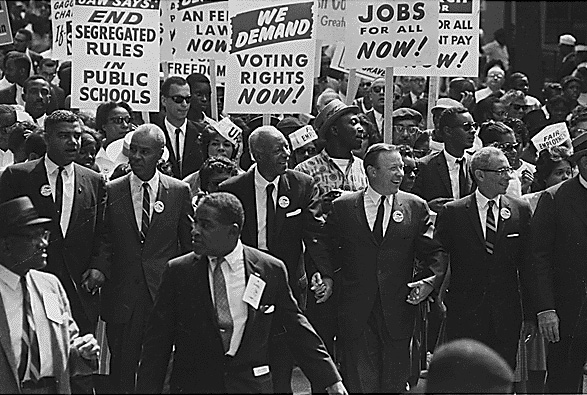

Organizations such as the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE), Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and the more militant Black Panthers focused on activism to promote change. Martin Luther King, Jr. advocated peaceful resistance. The March on Washington was organized to pressure Congress to adopt civil rights legislation. While President John F. Kennedy supported civil rights initiatives, legislation was not passed until after his assassination. In time, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965 made discrimination and racial segregation illegal.

Jim Crow and African American Life

Just as reformers advocated for business regulations, anti-trust laws, environmental protections, women’s rights, and urban health campaigns, so too did many push for racial legislation in the American South. America’s tragic racial history was not erased by the Progressive Era. In fact, in all too many ways, reform removed African Americans ever farther from American public life.

In the South, electoral politics remained a parade of electoral fraud, voter intimidation, and race-baiting. Democratic Party candidates stirred southern whites into frenzies with warnings of “negro domination” and of black men violating white women. The region’s culture of racial violence and the rise of lynching as a mass public spectacle accelerated. And as the remaining African American voters threatened to the dominance of Democratic leadership in the South, southern Democrats turned to what many white southerners understood as a series of progressive electoral and social reforms—disenfranchisement and segregation. Just as reformers would clean up politics by taming city political machines, white southerners would “purify” the ballot box by restricting black voting and they would prevent racial strife by legislating the social separation of the races. The strongest supporters of such measures in the South movement were progressive Democrats and former Populists, both of whom saw in these reforms a way to eliminate the racial demagoguery that conservative Democratic party leaders had so effectively wielded. Leaders in both the North and South embraced and proclaimed the reunion of the sections on the basis of a shared Anglo-Saxon, white supremacy. As the nation took up the “white man’s burden” to uplift the world’s racially inferior peoples, the North looked to the South as an example of how to manage non-white populations. The South had become the nation’s racial vanguard.

The question was how to accomplish disfranchisement. The 15th Amendment clearly prohibited states from denying any citizen the right to vote on the basis of race. In 1890, a Mississippi state newspaper called on politicians to devise “some legal defensible substitute for the abhorrent and evil methods on which white supremacy lies.” The state’s Democratic Party responded with a new state constitution designed to purge corruption at the ballot box through disenfranchisement. African Americans hoping to vote in Mississippi would have to jump through a series of hurdles designed with the explicit purpose of excluding them from political power. The state first established a poll tax, which required voters to pay for the privilege of voting. Second, it stripped the suffrage from those convicted of petty crimes most common among the state’s African Americans. Next, the state required voters to pass a literacy test. Local voting officials, who were themselves part of the local party machine, were responsible for judging whether voters were able to read and understand a section of the Constitution. In order to protect illiterate whites from exclusion, the so called “understanding clause” allowed a voter to qualify if they could adequately explain the meaning of a section that was read to them. In practice these rules were systematically abused to the point where local election officials effectively wielded the power to permit and deny suffrage at will. The disenfranchisement laws effectively moved electoral conflict from the ballot box, where public attention was greatest, to the voting registrar, where supposedly color-blind laws allowed local party officials to deny the ballot without the appearance of fraud.

Between 1895 and 1908 the rest of the states in the South approved new constitutions including these disenfranchisement tools. Six southern states also added a grandfather clause, which bestowed the suffrage on anyone whose grandfather was eligible to vote in 1867. This ensured that whites who would have been otherwise excluded through mechanisms such as poll taxes or literacy tests would still be eligible, at least until grandfather clauses were struck down by the Supreme Court in 1915. Finally, each southern state adopted an all-white primary, excluded blacks from the Democratic primary, the only political contests that mattered across much of the South.

For all the legal double-talk, the purpose of these laws was plain. James Kimble Vardaman, later Governor of Mississippi, boasted “there is no use to equivocate or lie about the matter. Mississippi’s constitutional convention was held for no other purpose than to eliminate the nigger from politics; not the ignorant—but the nigger.”31These technically colorblind tools did their work well. In 1900 Alabama had 121,159 literate black men of voting age. Only 3,742 were registered to vote. Louisiana had 130,000 black voters in the contentious election of 1896. Only 5,320 voted in 1900. Blacks were clearly the target of these laws, but that did not prevent some whites from being disenfranchised as well. Louisiana dropped 80,000 white voters over the same period. Most politically engaged southern whites considered this a price worth paying in order to prevent the fraud that had plagued the region’s elections.

At the same time that the South’s Democratic leaders were adopting the tools to disenfranchise the region’s black voters, these same legislatures were constructing a system of racial segregation even more pernicious. While it built on earlier practice, segregation was primarily a modern and urban system of enforcing racial subordination and deference. In rural areas, white and black southerners negotiated the meaning of racial difference within the context of personal relationships of kinship and patronage. An African American who broke the local community’s racial norms could expect swift personal sanction that often included violence. The crop lien and convict lease systems were the most important legal tools of racial control in the rural South. Maintaining white supremacy there did not require segregation. Maintaining white supremacy within the city, however, was a different matter altogether. As the region’s railroad networks and cities expanded, so too did the anonymity and therefore freedom of southern blacks. Southern cities were becoming a center of black middle class life that was an implicit threat to racial hierarchies. White southerners created the system of segregation as a way to maintain white supremacy in restaurants, theaters, public restrooms, schools, water fountains, train cars, and hospitals. Segregation inscribed the superiority of whites and the deference of blacks into the very geography of public spaces.

As with disenfranchisement, segregation violated a plain reading of the constitution—in this case the Fourteenth Amendment. Here the Supreme Court intervened, ruling in the Civil Rights Cases (1883) that the Fourteenth Amendment only prevented discrimination directly by states. It did not prevent discrimination by individuals, businesses, or other entities. Southern states exploited this interpretation with the first legal segregation of railroad cars in 1888. In a case that reached the Supreme Court in 1896, New Orleans resident Homer Plessy challenged the constitutionality of Louisiana’s segregation of streetcars. The court ruled against Plessy and, in the process, established the legal principle of separate but equal. Racially segregated facilities were legal provided they were equivalent. In practice this was rarely the case. The court’s majority defended its position with logic that reflected the racial assumptions of the day. “If one race be inferior to the other socially,” the court explained, “the Constitution of the United States cannot put them upon the same plane.” Justice John Harlan, the lone dissenter, countered, “our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law” Harlan went on to warn that the court’s decision would “permit the seeds of race hatred to be planted under the sanction of law.” In their rush to fulfill Harlan’s prophecy, southern whites codified and enforced the segregation of public spaces.

Segregation was built on a fiction—that there could be a white South socially and culturally distinct from African Americans. Its legal basis rested on the constitutional fallacy of “separate but equal.” Southern whites erected a bulwark of white supremacy that would last for nearly sixty years. Segregation and disenfranchisement in the South rejected black citizenship and relegated black social and cultural life to segregated spaces. African Americans lived divided lives, acting the part whites demanded of them in public, while maintaining their own world apart from whites. This segregated world provided a measure of independence for the region’s growing black middle class, yet at the cost of poisoning the relationship between black and white. Segregation and disenfranchisement created entrenched structures of racism that completed the total rejection of the promises of Reconstruction.

And yet, many black Americans of the Progressive Era fought back. Just as activists such as Ida Wells worked against southern lynching, Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois vied for leadership among African American activists, resulting in years of intense rivalry and debated strategies for the uplifting of black Americans.

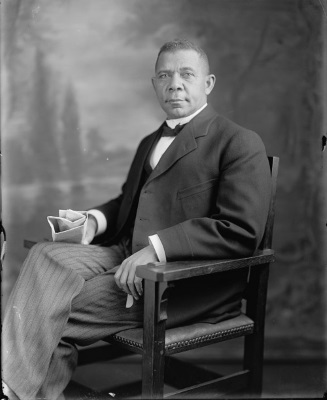

Born into the world of bondage in Virginia in 1856, Booker Taliaferro Washington was subjected to the degradation and exploitation of slavery early in life. But Washington also developed an insatiable thirst to learn. Working against tremendous odds, Washington matriculated into Hampton University in Virginia and thereafter established a southern institution that would educate many black Americans, the Tuskegee Institute. Located in Alabama, Washington envisioned Tuskegee’s contribution to black life to come through industrial education and vocational training. He believed that such skills would help African Americans too accomplish economic independence while developing a sense of self-worth and pride of accomplishment, even while living within the putrid confines of Jim Crow. Washington poured his life into Tuskegee, and thereby connected with leading white philanthropic interests. Individuals such as Andrew Carnegie, for instance, financially assisted Washington and his educational ventures.

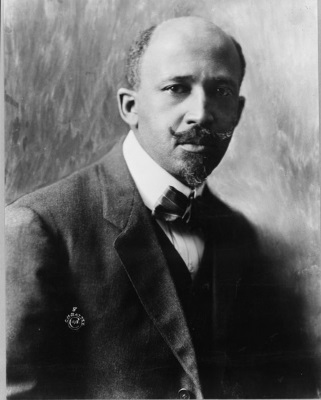

The strategies of Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois differed, but their desire remained the same: better lives for African Americans. Harris & Ewing, “WASHINGTON BOOKER T,” between 1905 and 1915. Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/hec2009002812/.

As a leading spokesperson for black Americans at the turn of the twentieth century, particularly after Frederick Douglass’s exit from the historical stage in early 1895, Washington’s famous “Atlanta Compromise” speech from that same year encouraged black Americans to “cast your bucket down” to improve life’s lot under segregation. In the same speech, delivered one year before the Supreme Court’s Plessy v. Ferguson decision that legalized segregation under the “separate but equal” doctrine, Washington said to white Americans, “In all things that are purely social we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress.”34 Both praised as a race leader and pilloried as an accommodationist to America’s unjust racial hierarchy, Washington’s public advocacy of a conciliatory posture towards white supremacy concealed the efforts to which Washington went to assist African Americans in the legal and economic quest for racial justice. In addition to founding Tuskegee, Washington also published a handful of influential books, including the autobiography Up from Slavery (1901). Like Du Bois, Washington was also active in black journalism, working to fund and support black newspaper publications, most of which sought to counter Du Bois’s growing influence. Washington died in 1915, during World War I, of ill health in Tuskegee, Alabama.

Speaking decades later, W.E.B. Du Bois said Washington had, in his 1895 “Compromise” speech, “implicitly abandoned all political and social rights. . . I never thought Washington was a bad man . . . I believed him to be sincere, though wrong.” Du Bois would directly attack Washington in his classic 1903 The Souls of Black Folk, but at the turn of the century he could never escape the shadow of his longtime rival. “I admired much about him,” Du Bois admitted, “Washington . . . died in 1915. A lot of people think I died at the same time.”

Du Bois’s criticism reveals the politicized context of the black freedom struggle and exposes the many positions available to black activists. Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, in 1868, W. E. B. Du Bois entered the world as a free person of color three years after the Civil War ended. Raised by a hardworking and independent mother, Du Bois’s New England childhood alerted him to the reality of race even as it invested the emerging thinker with an abiding faith in the power of education. Du Bois graduated at the top of his high school class and attended Fisk University. Du Bois’s sojourn to the South in 1880s left a distinct impression that would guide his life’s work to study what he called the “Negro problem,” the systemic racial and economic discrimination that Du Bois prophetically pronounced would be the problem of the twentieth century. After Fisk, Du Bois’s educational path trended back North, and he attended Harvard, earned his second degree, crossed the Atlantic for graduate work in Germany, and circulated back to Harvard and in 1895—the same year as Washington’s famous Atlanta address—became the first black American to receive a Ph.D. there.

Du Bois became one of America’s foremost intellectual leaders on questions of social justice by producing scholarship that underscored the humanity of African Americans. Du Bois’s work as an intellectual, scholar, and college professor began during the Progressive Era, a time in American history marked by rapid social and cultural change as well as complex global political conflicts and developments. Du Bois addressed these domestic and international concerns not only his classrooms at Wilberforce University in Ohio and Atlanta University in Georgia, but also in a number of his early publications on the history of the transatlantic slave trade and black life in urban Philadelphia. The most well-known of these early works included The Souls of Black Folk (1903) and Darkwater (1920). In these books, Du Bois combined incisive historical analysis with engaging literary drama to validate black personhood and attack the inhumanity of white supremacy, particularly in the lead up to and during World War I. In addition to publications and teaching, Du Bois set his sights on political organizing for civil rights, first with the Niagara Movement and later with its offspring the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Du Bois’s main work with the NAACP lasted from 1909 to 1934 as editor of The Crisis, one of America’s leading black publications. Du Bois attacked Washington and urged black Americans to concede to nothing, to make no compromises and advocate for equal rights under the law. Throughout his early career, he pushed for civil rights legislation, launched legal challenges against discrimination, organized protests against injustice, and applied his capacity for clear research and sharp prose to expose the racial sins of Progressive Era America.

W. E. B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington made a tremendous historical impact and left a notable historical legacy. Reared in different settings, early life experiences and even personal temperaments oriented both leader’s lives and outlooks in decidedly different ways. Du Bois’s confrontational voice boldly targeted white supremacy. He believed in the power of social science to arrest the reach of white supremacy. Washington advocated incremental change for longer-term gain. He contended that economic self-sufficiency would pay off at a future date. Although Du Bois directly spoke out against Washington in the chapter “Of Mr. Booker T. Washington” in Souls of Black Folk, four years later in 1907 they shared the same lectern at Philadelphia Divinity School to address matters of race, history, and culture in the American South. As much as the philosophies of Du Bois and Washington diverged when their lives overlapped, highlighting their respective quests for racial and economic justice demonstrates the importance of understanding the multiple strategies used to demand that America live up to its democratic creed.

American YAWP: Jim Crow and the African American Life Retrieved September 1, 2017 from http://www.americanyawp.com/text/20-the-progressive-era/

The Civil Rights Movement

Change From the Bottom Up

For many people inspired by the victories of Brown v. Board of Education and the Montgomery Bus Boycott, the glacial pace of progress in the segregated South was frustrating if not intolerable. In some places, such as Greensboro, North Carolina, local NAACP chapters had been influenced by whites who provided financing for the organization. This aid, together with the belief that more forceful efforts at reform would only increase white resistance, had persuaded some African American organizations to pursue a “politics of moderation” instead of attempting to radically alter the status quo. Martin Luther King Jr.’s inspirational appeal for peaceful change in the city of Greensboro in 1958, however, planted the seed for a more assertive civil rights movement.

On February 1, 1960, four sophomores at the North Carolina Agricultural & Technical College in Greensboro—Ezell Blair, Jr., Joseph McNeil, David Richmond, and Franklin McCain—entered the local Woolworth’s and sat at the lunch counter. The lunch counter was segregated, and they were refused service as they knew they would be. They had specifically chosen Woolworth’s, because it was a national chain and was thus believed to be especially vulnerable to negative publicity. Over the next few days, more protesters joined the four sophomores. Hostile whites responded with threats and taunted the students by pouring sugar and ketchup on their heads. The successful six-month-long Greensboro sit-in initiated the student phase of the African American civil rights movement and, within two months, the sit-in movement had spread to fifty-four cities in nine states.

Businesses such as this one were among those that became targets of activists protesting segregation. Segregated businesses could be found throughout the United States; this one was located in Ohio. (credit: Library of Congress)

In the words of grassroots civil rights activist Ella Baker, the students at Woolworth’s wanted more than a hamburger; the movement they helped launch was about empowerment. Baker pushed for a “participatory Democracy” that built on the grassroots campaigns of active citizens instead of deferring to the leadership of educated elites and experts. As a result of her actions, in April 1960, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) formed to carry the battle forward. Within a year, more than one hundred cities had desegregated at least some public accommodations in response to student-led demonstrations. The sit-ins inspired other forms of nonviolent protest intended to desegregate public spaces. “Sleep-ins” occupied motel lobbies, “read-ins” filled public libraries, and churches became the sites of “pray-ins.”

Students also took part in the 1961 “freedom rides” sponsored by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and SNCC. The intent of the African American and white volunteers who undertook these bus rides south was to test enforcement of a U.S. Supreme Court decision prohibiting segregation on interstate transportation and to protest segregated waiting rooms in southern terminals. Departing Washington, DC, on May 4, the volunteers headed south on buses that challenged the seating order of Jim Crow segregation. Whites would ride in the back, African-Americans would sit in the front, and on other occasions, riders of different races would share the same bench seat. The freedom riders encountered little difficulty until they reached Rock Hill, South Carolina, where a mob severely beat John Lewis, a freedom rider who later became chairman of SNCC (Figure). The danger increased as the riders continued through Georgia into Alabama, where one of the two buses was firebombed outside the town of Anniston. The second group continued to Birmingham, where the riders were attacked by the Ku Klux Klan as they attempted to disembark at the city bus station. The remaining volunteers continued to Mississippi, where they were arrested when they attempted to desegregate the waiting rooms in the Jackson bus terminal.

Free By ’63 (OR ’64 OR ’65)

The grassroots efforts of people like the Freedom Riders to change discriminatory laws and longstanding racist traditions grew more widely known in the mid-1960s. The approaching centennial of Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation spawned the slogan “Free by ’63” among civil rights activists. As African Americans increased their calls for full rights for all Americans, many civil rights groups changed their tactics to reflect this new urgency.

Perhaps the most famous of the civil rights-era demonstrations was the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, held in August 1963, on the one hundredth anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. Its purpose was to pressure President Kennedy to act on his promises regarding civil rights. The date was the eighth anniversary of the brutal racist murder of fourteen-year-old Emmett Till in Money, Mississippi. As the crowd gathered outside the Lincoln Memorial and spilled across the National Mall (Figure), Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his most famous speech. In “I Have a Dream,” King called for an end to racial injustice in the United States and envisioned a harmonious, integrated society. The speech marked the high point of the civil rights movement and established the legitimacy of its goals. However, it did not prevent white terrorism in the South, nor did it permanently sustain the tactics of nonviolent civil disobedience.

\

Other gatherings of civil rights activists ended tragically, and some demonstrations were intended to provoke a hostile response from whites and thus reveal the inhumanity of the Jim Crow laws and their supporters. In 1963, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) led by Martin Luther King, Jr. mounted protests in some 186 cities throughout the South. The campaign in Birmingham that began in April and extended into the fall of 1963 attracted the most notice, however, when a peaceful protest was met with violence by police, who attacked demonstrators, including children, with fire hoses and dogs. The world looked on in horror as innocent people were assaulted and thousands arrested. King himself was jailed on Easter Sunday, 1963, and, in response to the pleas of white clergymen for peace and patience, he penned one of the most significant documents of the struggle—“Letter from a Birmingham Jail.” In the letter, King argued that African Americans had waited patiently for more than three hundred years to be given the rights that all human beings deserved; the time for waiting was over.

Some of the greatest violence during this era was aimed at those who attempted to register African Americans to vote. In 1964, SNCC, working with other civil rights groups, initiated its Mississippi Summer Project, also known as Freedom Summer. The purpose was to register African American voters in one of the most racist states in the nation. Volunteers also built “freedom schools” and community centers. SNCC invited hundreds of white middle-class students, mostly from the North, to help in the task. Many volunteers were harassed, beaten, and arrested, and African American homes and churches were burned. Three civil rights workers, James Chaney, Michael Schwerner, and Andrew Goodman, were killed by the Ku Klux Klan. That summer, civil rights activists Fannie Lou Hamer, Ella Baker, and Robert Parris Moses formally organized the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) as an alternative to the all-white Mississippi Democratic Party. The Democratic National Convention’s organizers, however, would allow only two MFDP delegates to be seated, and they were confined to the roles of nonvoting observers.

The vision of whites and African Americans working together peacefully to end racial injustice suffered a severe blow with the death of Martin Luther King, Jr. in Memphis, Tennessee, in April 1968. King had gone there to support sanitation workers trying to unionize. In the city, he found a divided civil rights movement; older activists who supported his policy of nonviolence were being challenged by younger African Americans who advocated a more militant approach. On April 4, King was shot and killed while standing on the balcony of his motel. Within hours, the nation’s cities exploded with violence as angry African Americans, shocked by his murder, burned and looted inner-city neighborhoods across the country. While whites recoiled from news about the riots in fear and dismay, they also criticized African Americans for destroying their own neighborhoods; they did not realize that most of the violence was directed against businesses that were not owned by blacks and that treated African American customers with suspicion and hostility.

Many businesses, such as those in this neighborhood at the intersection of 7th and N Streets in NW, Washington, DC, were destroyed in riots that followed the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr.

Black Frustration, Black Power

The episodes of violence that accompanied Martin Luther King Jr.’s murder were but the latest in a string of urban riots that had shaken the United States since the mid-1960s. Between 1964 and 1968, there were 329 riots in 257 cities across the nation. In 1964, riots broke out in Harlem and other African American neighborhoods. In 1965, a traffic stop set in motion a chain of events that culminated in riots in Watts, an African American neighborhood in Los Angeles. Thousands of businesses were destroyed, and, by the time the violence ended, thirty-four people were dead, most of them African Americans killed by the Los Angeles police and the National Guard. More riots took place in 1966 and 1967.

Frustration and anger lay at the heart of these disruptions. Despite the programs of the Great Society, good healthcare, job opportunities, and safe housing were abysmally lacking in urban African American neighborhoods in cities throughout the country, including in the North and West, where discrimination was less overt but just as crippling. In the eyes of many rioters, the federal government either could not or would not end their suffering, and most existing civil rights groups and their leaders had been unable to achieve significant results toward racial justice and equality. Disillusioned, many African Americans turned to those with more radical ideas about how best to obtain equality and justice.

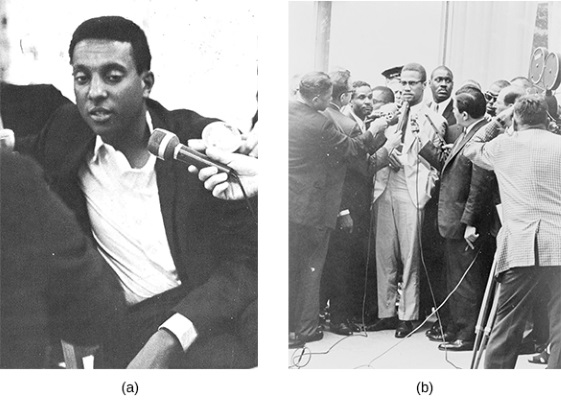

Within the chorus of voices calling for integration and legal equality were many that more stridently demanded empowerment and thus supported Black Power. Black Power meant a variety of things. One of the most famous users of the term was Stokely Carmichael, the chairman of SNCC, who later changed his name to Kwame Ture. For Carmichael, Black Power was the power of African Americans to unite as a political force and create their own institutions apart from white-dominated ones, an idea first suggested in the 1920s by political leader and orator Marcus Garvey. Like Garvey, Carmichael became an advocate of black separatism, arguing that African Americans should live apart from whites and solve their problems for themselves. In keeping with this philosophy, Carmichael expelled SNCC’s white members. He left SNCC in 1967 and later joined the Black Panthers (see below).

Long before Carmichael began to call for separatism, the Nation of Islam, founded in 1930, had advocated the same thing. In the 1960s, its most famous member was Malcolm X, born Malcolm Little (Figure). The Nation of Islam advocated the separation of white Americans and African Americans because of a belief that African Americans could not thrive in an atmosphere of white racism. Indeed, in a 1963 interview, Malcolm X, discussing the teachings of the head of the Nation of Islam in America, Elijah Muhammad, referred to white people as “devils” more than a dozen times. Rejecting the nonviolent strategy of other civil rights activists, he maintained that violence in the face of violence was appropriate.

Stokely Carmichael (a), one of the most famous and outspoken advocates of Black Power, is surrounded by members of the media after speaking at Michigan State University in 1967. Malcolm X (b) was raised in a family influenced by Marcus Garvey and persecuted for its outspoken support of civil rights. While serving a stint in prison for armed robbery, he was introduced to and committed himself to the Nation of Islam. (credit b: modification of work by Library of Congress)

In 1964, after a trip to Africa, Malcolm X left the Nation of Islam to found the Organization of Afro-American Unity with the goal of achieving freedom, justice, and equality “by any means necessary.” His views regarding black-white relations changed somewhat thereafter, but he remained fiercely committed to the cause of African American empowerment. On February 21, 1965, he was killed by members of the Nation of Islam. Stokely Carmichael later recalled that Malcolm X had provided an intellectual basis for Black Nationalism and given legitimacy to the use of violence in achieving the goals of Black Power.

Unlike Stokely Carmichael and the Nation of Islam, most Black Power advocates did not believe African Americans needed to separate themselves from white society. The Black Panther Party, founded in 1966 in Oakland, California, by Bobby Seale and Huey Newton, believed African Americans were as much the victims of capitalism as of white racism. Accordingly, the group espoused Marxist teachings, and called for jobs, housing, and education, as well as protection from police brutality and exemption from military service in their Ten Point Program. The Black Panthers also patrolled the streets of African American neighborhoods to protect residents from police brutality, yet sometimes beat and murdered those who did not agree with their cause and tactics. Their militant attitude and advocacy of armed self-defense attracted many young men but also led to many encounters with the police, which sometimes included arrests and even shootouts, such as those that took place in Los Angeles, Chicago and Carbondale, Illinois.

The self-empowerment philosophy of Black Power influenced mainstream civil rights groups such as the National Economic Growth Reconstruction Organization (NEGRO), which sold bonds and operated a clothing factory and construction company in New York, and the Opportunities Industrialization Center in Philadelphia, which provided job training and placement—by 1969, it had branches in seventy cities. Black Power was also part of a much larger process of cultural change. The 1960s composed a decade not only of Black Power but also of Black Pride. African American abolitionist John S. Rock had coined the phrase “Black Is Beautiful” in 1858, but in the 1960s, it became an important part of efforts within the African American community to raise self-esteem and encourage pride in African ancestry. Black Pride urged African Americans to reclaim their African heritage and, to promote group solidarity, to substitute African and African-inspired cultural practices, such as handshakes, hairstyles, and dress, for white practices. One of the many cultural products of this movement was the popular television music program Soul Train, created by Don Cornelius in 1969, which celebrated black culture and aesthetics.

The Mexican American Fight for Civil Rights

The African American bid for full citizenship was surely the most visible of the battles for civil rights taking place in the United States. However, other minority groups that had been legally discriminated against or otherwise denied access to economic and educational opportunities began to increase efforts to secure their rights in the 1960s. Like the African American movement, the Mexican American civil rights movement won its earliest victories in the federal courts. In 1947, in Mendez v. Westminster, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit ruled that segregating children of Hispanic descent was unconstitutional. In 1954, the same year as Brown v. Board of Education, Mexican Americans prevailed in Hernandez v. Texas, when the U.S. Supreme Court extended the protections of the Fourteenth Amendment to all ethnic groups in the United States.

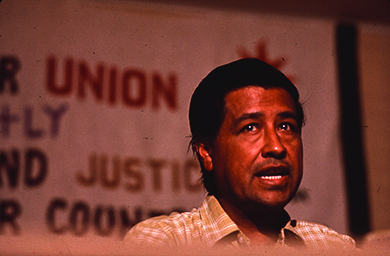

The highest-profile struggle of the Mexican American civil rights movement was the fight that Caesar Chavez (Figure) and Dolores Huerta waged in the fields of California to organize migrant farm workers. In 1962, Chavez and Huerta founded the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA). In 1965, when Filipino grape pickers led by Filipino American Larry Itliong went on strike to call attention to their plight, Chavez lent his support. Workers organized by the NFWA also went on strike, and the two organizations merged to form the United Farm Workers. When Chavez asked American consumers to boycott grapes, politically conscious people around the country heeded his call, and many unionized longshoremen refused to unload grape shipments. In 1966, Chavez led striking workers to the state capitol in Sacramento, further publicizing the cause. Martin Luther King, Jr. telegraphed words of encouragement to Chavez, whom he called a “brother.” The strike ended in 1970 when California farmers recognized the right of farm workers to unionize. However, the farm workers did not gain all they sought, and the larger struggle did not end.

Cesar Chavez was influenced by the nonviolent philosophy of Indian nationalist Mahatma Gandhi. In 1968, he emulated Gandhi by engaging in a hunger strike.

The equivalent of the Black Power movement among Mexican Americans was the Chicano Movement. Proudly adopting a derogatory term for Mexican Americans, Chicano activists demanded increased political power for Mexican Americans, education that recognized their cultural heritage, and the restoration of lands taken from them at the end of the Mexican-American War in 1848. One of the founding members, Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales, launched the Crusade for Justice in Denver in 1965, to provide jobs, legal services, and healthcare for Mexican Americans. From this movement arose La Raza Unida, a political party that attracted many Mexican American college students. Elsewhere, Reies López Tijerina fought for years to reclaim lost and illegally expropriated ancestral lands in New Mexico; he was one of the co-sponsors of the Poor People’s March on Washington in 1967.

The Civil Rights Movement Retrieved September 1, 2017 from https://cnx.org/contents/PZ1CQGx3@1/The-Civil-Rights-Movement

Summary

The movement for civil rights in the United States was defined by oppressive legislation and episodes of activism. Jim Crow laws enabled southern states to relegate black Americans to the status of second class citizen. The Supreme Court decision of Plessy v. Ferguson legalized racial segregation in public facilities, including education, under the phrase “separate but equal.” This became a defining statement of white superiority and led to voter suppression and, later, racial violence.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NCAACP) was created in 1909 to promote racial equality and an end to racial discrimination. Key founding members include W.E.B. DuBois, Ida B. Wells, and Archibald Grimke. In its early years, the NAACP focused on overturning legislation that disenfranchised black Americans. By 1913, they organized in response to President Woodrow Wilson’s initiatives toward racial segregation in the workplace and in hiring practices.

By the 1950s, black leadership began to adopt strategies that included non-violent direct action, sometimes leading to civil disobedience and/or acts of nonviolent resistance. They employed tactics such as sit-ins, boycotts, and marches. The Montgomery Bus Boycott and Greensboro Sit-In made headlines around the country. The violence surrounding the forced integration of Little Rock Central High School and the death of Emmett Till made obvious the challenges in formulating a response to such racial discrimination. The nonviolent resistance movement was not the only response to such episodes, but was the most prominent.

In 1954, the Supreme Court overturned Plessy v. Ferguson by issuing the Brown v. Board of Education ruling stating that “separate but equal” was unconstitutional. At the same time the Black Power movement gained steam. The Black Panther Party advocated for the right of self-determination and resistance to assimilation. Stokely Carmichael led the more militant approach to change. Following the assassination of Malcolm X in 1965, he offered a strong avocation for leaving white culture behind in an effort to embrace black history and culture. Likewise, southerners were not without their own stern response to the Brown decision. In the Southern Manifesto, Southern Congressman denounced the Supreme Court’s decision and vowed to resist. Ultimately, federal intervention became necessary to enforce the decision.

The movement was not without setbacks. In June 1963, NAACP activist Medgar Evars was killed. Just five months later, President Kennedy was assassinated. Many believed the civil rights bill would stall in Congress. However, President Lyndon Johnson turned out to be a strong voice against racial injustice. In June 1964, he signed into law the Civil Rights Act of 1964 that, in part, created the Equal Opportunity Employment Commission (EOEC).

One of the more serious blows to progress came in April 1968 when Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated. Although he organized the March on Washington to pressure Congress for protective legislation, his presence and constant advocacy of nonviolent resistance was a key element to the civil rights movement. The guidance of Martin Luther King, Jr. led to a policy of affirmative action in hiring practices and higher education admissions. The military slowly shed the discriminatory segregation practices within its ranks and began to integrate forces.

Overall, progress towards legal equality and equality of opportunity was slow and uncertain. The 2008 election of Barack Obama, the country’s first African American president highlighted this uneven progress. A generation ago, the election of an African American man as the leader of the country would have perhaps been an unimaginable event, so the election was a milestone in the struggle for equality. Nevertheless, persistent gaps in areas of wealth, education, and homeownership revealed that equality was still elusive. The number of shootings by police of African American men revealed that racism was still an issue.