21

Urbanization and industrialization led to many economic challenges for the United States, and over the years successive governments have implemented economic policies to address these challenges.

Contemporary Economic Policies

Urbanization and industrialization led to many economic challenges for the United States and over the years successive governments have implemented economic policies to address these challenges.

The Reagan Years

Working- and middle-class Americans, especially those of color, struggled to maintain economic equilibrium during the Reagan years. The growing national debt generated fresh economic pain. The federal government borrowed money to finance the debt, raising interest rates to heighten the appeal of government bonds. Foreign money poured into the United States, raising the value of the dollar and attracting an influx of goods from overseas. The imbalance between American imports and exports grew from $36 billion in 1980 to $170 billion in 1987.62 Foreign competition battered the already anemic manufacturing sector. The appeal of government bonds likewise drew investment away from American industry.

Continuing an ongoing trend, many steel and automobile factories in the industrial Northeast and Midwest closed or moved overseas during the 1980s. Bruce Springsteen, the self-appointed bard of blue-collar America, offered eulogies to Rust Belt cities in songs like “Youngstown” and “My Hometown,” in which the narrator laments that his “foreman says these jobs are going boys/and they ain’t coming back.”63 Competition from Japanese carmakers spurred a “Buy American” campaign. Meanwhile, a “farm crisis” gripped the rural United States. Expanded world production meant new competition for American farmers, while soaring interest rates caused the already sizable debt held by family farms to mushroom. Farm foreclosures skyrocketed during Reagan’s tenure. In September 1985, prominent musicians including Neil Young and Willie Nelson organized “Farm Aid,” a benefit concert at the University of Illinois’s football stadium designed to raise money for struggling farmers.

At the other end of the economic spectrum, wealthy Americans thrived thanks to the policies of the New Right. The financial industry found new ways to earn staggering profits during the Reagan years. Wall Street brokers like “junk bond king” Michael Milken reaped fortunes selling high-risk, high-yield securities. Reckless speculation helped drive the stock market steadily upward until the crash of October 19, 1987. On “Black Friday,” the market plunged 800 points, erasing 13% of its value. Investors lost more than $500 billion.64 An additional financial crisis loomed in the savings and loan industry, and Reagan’s deregulatory policies bore significant responsibility. In 1982 Reagan signed a bill increasing the amount of federal insurance available to savings and loan depositors, making those financial institutions more popular with consumers. The bill also allowed “S & L’s” to engage in high-risk loans and investments for the first time. Many such deals failed catastrophically, while some S &L managers brazenly stole from their institutions. In the late 1980s, S & L’s failed with regularity, and ordinary Americans lost precious savings. The 1982 law left the government responsible for bailing out S&L’s out at an eventual cost of $132 billion.65

The Clinton Years

In his first term, Clinton set out an ambitious agenda that included an economic stimulus package, universal health insurance, a continuation of the Middle East peace talks initiated by Bush’s Secretary of State James Baker, welfare reform, and a completion of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) to abolish trade barriers between the U.S., Mexico, and Canada. His moves to reform welfare, open trade, and deregulate financial markets were particular hallmarks of Clinton’s “Third Way,” a political middle path that synthesized liberal and conservative ideas.11

With NAFTA, Clinton, reversed decades of Democratic opposition to free trade and opened the nation’s northern and southern borders to the free flow of capital and goods. Critics, particularly in the Midwest’s Rust Belt, blasted the agreement for opening American workers to deleterious competition by low-paid foreign workers. Many American factories did relocate by setting up shops–maquilas–in northern Mexico that took advantage of Mexico’s low wages. Thousands of Mexicans rushed to the maquilas. Thousands more continued on past the border.

Bush and Obama

The Great Recession began, as most American economic catastrophes began, with the bursting of a speculative bubble. Throughout the 1990s and into the new millennium, home prices continued to climb, and financial services firms looked to cash in on what seemed to be a safe but lucrative investment. Especially after the dot-com bubble burst, investors searched for a secure investment that was rooted in clear value and not trendy technological speculation. And what could be more secure than real estate? But mortgage companies began writing increasingly risky loans and then bundling them together and selling them over and over again, sometimes so quickly that it became difficult to determine exactly who owned what.

Decades of financial deregulation had rolled back Depression Era restraints and again enabled risky business practices to dominate the world of American finance. It was a bipartisan agenda. In the 1990s, for instance, Bill Clinton signed the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, repealing provisions of the 1933 Glass-Steagall Act separating commercial and investment banks, and the Commodity Futures Modernization Act, which exempted credit-default swaps–perhaps the key financial mechanism behind the crash–from regulation.

Mortgages had been so heavily leveraged that when American homeowners began to default on their loans, the whole system collapsed. Major financial services firms such as Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers disappeared almost overnight. In order to prevent the crisis from spreading, the federal government poured billions of dollars into the industry, propping up hobbled banks. Massive giveaways to bankers created shock waves of resentment throughout the rest of the country. On the Right, conservative members of the Tea Party decried the cronyism of an Obama administration filled with former Wall Street executives. The same energies also motivated the Occupy Wall Street movement, as mostly young left-leaning New Yorkers protesting an American economy that seemed overwhelmingly tilted toward “the one percent.”21

The Great Recession only magnified already rising income and wealth inequalities. According to the Chief Investment Officer at JPMorgan Chase, the largest bank in the United States, “profit margins have reached levels not seen in decades,” and “reductions in wages and benefits explain the majority of the net improvement.”22 A study from the Congressional Budget authority found that since the late 1970s, after-tax benefits of the wealthiest 1% grew by over 300%. The “average” American’s had grown 35%. Economic trends have disproportionately and objectively benefited the wealthiest Americans. Still, despite political rhetoric, American frustration failed to generate anything like the social unrest of the early twentieth century. A weakened labor movement and a strong conservative bloc continue to stymie serious attempts at redistributing wealth. Occupy Wall Street managed to generate a fair number of headlines and shift public discussion away from budget cuts and toward inequality, but its membership amounted to only a fraction of the far more influential and money-driven Tea Party. Its presence on the public stage was fleeting.

The Great Recession, however, was not. While American banks quickly recovered and recaptured their steady profits, and the American stock market climbed again to new heights, American workers continued to lag. Job growth would remain miniscule and unemployment rates would remain stubbornly high. Wages froze, meanwhile, and well-paying full-time jobs that were lost were too often replaced by low-paying, part-time work. A generation of workers coming of age within the crisis, moreover, had been savaged by the economic collapse. Unemployment among young Americans hovered for years at rates nearly double the national average.

Attribution:

Eladio Bobadilla et al., “The Recent Past,” Michael Hammond, ed., in The American Yawp, Joseph Locke and Ben Wright, eds., last modified August 1, 2016, II. American Politics before September 11, 2001

Eladio Bobadilla et al., “The Recent Past,” Michael Hammond, ed., in The American Yawp, Joseph Locke and Ben Wright, eds., last modified August 1, 2016, V. The Great Recession

Richard Anderson et al., “The Triumph of the Right,” Richard Anderson and William J. Schultz, eds., in The American Yawp, Joseph Locke and Ben Wright, eds., last modified August 1, 2016.

Learning and Earning

The quality of American education remains a challenge. The global economy is dominated by those nations with the greatest number of “knowledge workers:” people with specialized knowledge and skills like engineers, scientists, doctors, teachers, financial analysts, and computer programmers. Furthermore, American students’ reading, math, and critical thinking skills are less developed than those of their peers in other industrialized nations, including small countries like Estonia.

The Obama administration sought to make higher education more accessible by increasing the amount that students could receive under the federally funded Pell Grant Program, which, by the 2012–13 academic year, helped 9.5 million students pay for their college education. Obama also worked out a compromise with Congress in 2013, which lowered the interest rates charged on student loans. However, college tuition is still growing at a rate of 2 to 3 percent per year, and the debt burden has surpassed the $1 trillion mark and is likely to increase. With debt upon graduation averaging about $29,000, students may find their economic options limited. Instead of buying cars or paying for housing, they may have to join the boomerang generation and return to their parents’ homes in order to make their loan payments. Clearly, high levels of debt will affect their career choices and life decisions for the foreseeable future.

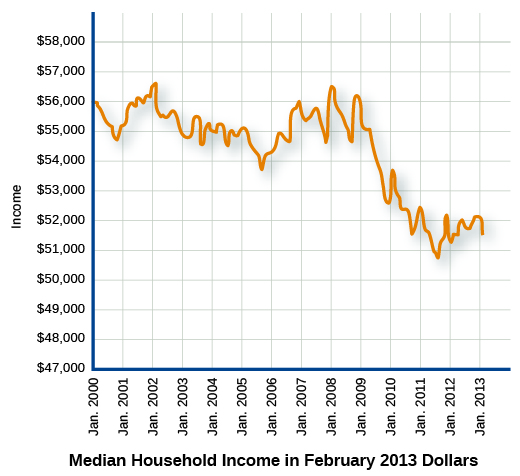

Many other Americans continue to be challenged by the state of the economy. Most economists calculate that the Great Recession reached its lowest point in 2009, and the economy has gradually improved since then. The stock market ended 2013 at historic highs, having experienced its biggest percentage gain since 1997. However, despite these gains, the nation struggled to maintain a modest annual growth rate of 2.5 percent after the Great Recession, and the percentage of the population living in poverty continues to hover around 15 percent. Income has decreased (Figure), and, as late as 2011, the unemployment rate was still high in some areas. Eight million full-time workers have been forced into part-time work, whereas 26 million seem to have given up and left the job market.

Median household income trends reveal a steady downward spiral. The Great Recession may have ended, but many remain worse off than they were in 2008.

Attribution:

OpenStax, U.S. History, OpenStax CNX, Aug16, 2017. https://cnx.org/contents/p7ovuIkl@3.84:A0PMfqds@4/Hope-and-Change

Summary

In the wake of economic issues that resulted from the effects of widespread industrialization and urbanization, different contemporary federal administrations–from Reagan to Clinton to Bush to Obama–have tackled these economic issues with differing tactics.

“Reaganomics” was the most serious attempt to change the course of U.S. economic policy of any administration since the New Deal. “Only by reducing the growth of government,” said Ronald Reagan, “can we increase the growth of the economy.” Reagan’s 1981 Program for Economic Recovery had four major policy objectives: (1) reduce the growth of government spending, (2) reduce the marginal tax rates on income from both labor and capital, (3) reduce regulation, and (4) reduce inflation by controlling the growth of the money supply. These major policy changes, in turn, were expected to increase saving and investment, increase economic growth, balance the budget, restore healthy financial markets, and reduce inflation and interest rates.

Clinton oversaw a very robust economy during his tenure. The U.S. had strong economic growth (around 4% annually) and record job creation (22.7 million). He raised taxes on higher income taxpayers early in his first term and cut defense spending, which contributed to a rise in revenue and decline in spending relative to the size of the economy. These factors helped bring the federal budget into surplus from fiscal years 1998-2001, the only surplus years after 1969. Debt held by the public, a primary measure of the national debt, fell relative to GDP throughout his two terms, from 47.8% in 1993 to 31.4% in 2001. Clinton signed NAFTA into law along with many other free trade agreements. He also enacted significant welfare reform. His deregulation of finance (both tacit and overt through the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act) has been criticized as a contributing factor to the Great Recession.

The economic policy of the Obama administration was characterized by moderate tax increases on higher income Americans designed to fund healthcare reform, reduce the federal budget deficit, and reduce income inequality. His first term (2009–2013) included measures designed to address the Great Recession and Subprime mortgage crisis, which began in 2007. These included a major stimulus package, banking regulation, and comprehensive healthcare reform.