5

On October 29, 1929, the stock market crashed. By 1932, nearly 2,300 banks had failed, and by 1933 unemployment had risen to nearly 25 percent. The Great Depression represented one of the worst financial crises in American history, and the American economy would not fully recover until World War II.

Although every region of the nation was affected by the Great Depression, the economic depression in the Great Plains was compounded by an environmental disaster known as the Dust Bowl. Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Arkansas were especially hard hit by decades of farming practices that depleted and over-plowed the topsoil. When severe droughts stretching from Texas to the Dakotas hit the region from 1932 until 1936, topsoil throughout the Great Plains turned to dust. The land, which had been so central to the success and livelihood of farmers in the Great Plains for generations, was no longer farmable.

By the middle of the 1930s the Great Plains had become an agricultural wasteland, and millions of “Okies” had become environmental refugees and were forced to leave their homes in search of employment. Simultaneously, many Americans living in urban areas were abandoning cities and traveling to the countryside in search of work. So many people were migrating out of the southwestern Great Plains states that local and state governments, who did not have the capacity or jobs to assist the migrants, began developing policies on migrants to make it more difficult for them to enter their communities and states. The Dust Bowl was a perfect storm – a combination of economic and environmental forces that produced some of the worst hardship of the Great Depression and affected countless Americans in the Great Plains.

The Live Experience of the Great Depression

In 1934 a woman from Humboldt County, California, wrote to First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt seeking a job for her husband, a surveyor, who had been out of work for nearly two years. The pair had survived on the meager income she received from working at the county courthouse. “My salary could keep us going,” she explained, “but—I am to have a baby.” The family needed temporary help, and, she explained, “after that I can go back to work and we can work out our own salvation. But to have this baby come to a home full of worry and despair, with no money for the things it needs, is not fair. It needs and deserves a happy start in life.”

As the United States slid ever deeper into the Great Depression, such tragic scenes played out time and time again. Individuals, families, and communities faced the painful, frightening, and often bewildering collapse of the economic institutions upon which they depended. The more fortunate were spared worst effects, and a few even profited from it, but by the end of 1932, the crisis had become so deep and so widespread that most Americans had suffered directly. Markets crashed through no fault of their own. Workers were plunged into poverty because of impersonal forces for which they shared no responsibility. With no safety net, they were thrown into economic chaos.

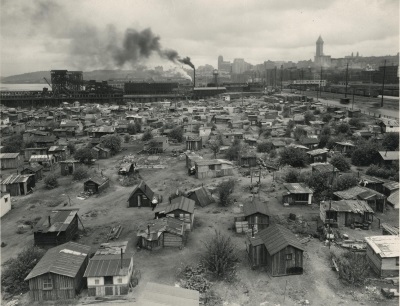

With rampant unemployment and declining wages, Americans slashed expenses. The fortunate could survive by simply deferring vacations and regular consumer purchases. Middle- and working-class Americans might rely upon disappearing credit at neighborhood stores, default on utility bills, or skip meals. Those that could borrowed from relatives or took in boarders in homes or “doubled up” in tenements. The most desperate, the chronically unemployed, encamped on public or marginal lands in “Hoovervilles,” spontaneous shantytowns that dotted America’s cities, depending upon breadlines and street-corner peddling. Poor women and young children entered the labor force, as they always had. The ideal of the “male breadwinner” was always a fiction for poor Americans, but the Depression decimated millions of new workers. The emotional and psychological shocks of unemployment and underemployment only added to the shocking material depravities of the Depression. Social workers and charity officials, for instance, often found the unemployed suffering from feelings of futility, anger, bitterness, confusion, and loss of pride. Such feelings affected the rural poor no less than the urban.

Attribution:

Cochran, Dana et al. The Great Depression. (n.d.). In The American Yawp. Retrieved September 9, 2017, from http://www.americanyawp.com/text/23-the-great-depression/

Migration and the Great Depression

On the Great Plains, environmental catastrophe deepened America’s longstanding agricultural crisis and magnified the tragedy of the Depression. Beginning in 1932, severe droughts hit from Texas to the Dakotas and lasted until at least 1936. The droughts compounded years of agricultural mismanagement. To grow their crops, Plains farmers had plowed up natural ground cover that had taken ages to form over the surface of the dry Plains states. Relatively wet decades had protected them, but, during the early 1930s, without rain, the exposed fertile topsoil turned to dust, and without sod or windbreaks such as trees, rolling winds churned the dust into massive storms that blotted out the sky, choked settlers and livestock, and rained dirt not only across the region but as far east as Washington, D.C., New England, and ships on the Atlantic Ocean. The “Dust Bowl,” as the region became known, exposed all-too-late the need for conservation. The region’s farmers, already hit by years of foreclosures and declining commodity prices, were decimated. For many in Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Arkansas who were “baked out, blown out, and broke,” their only hope was to travel west to California, whose rains still brought bountiful harvests and–potentially–jobs for farmworkers. It was an exodus. Oklahoma lost 440,000 people, or a full 18.4 percent of its 1930 population, to out-migration.

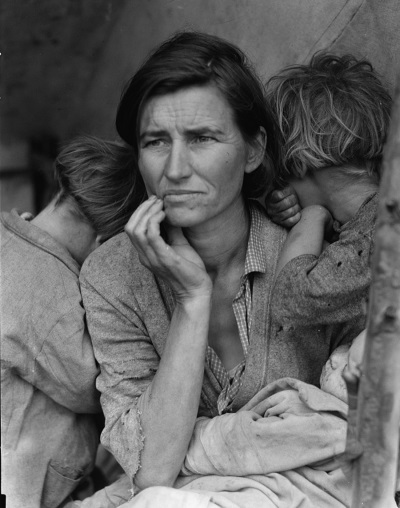

This iconic photograph made real the suffering of millions during the Great Depression. Dorothea Lange, “Destitute pea pickers in California. Mother of seven children. Age thirty-two. Nipomo, California” or “Migrant Mother,” February/March 1936. Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/fsa1998021539/PP/.

Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother became one of the most enduring images of the “Dust Bowl” and the ensuing westward exodus. Lange, a photographer for the Farm Security Administration, captured the image at migrant farmworker camp in Nipomo, California, in 1936. In the photograph a young mother stares out with a worried, weary expression. She was a migrant, having left her home in Oklahoma to follow the crops to the Golden State. She took part in what many in the mid-1930s were beginning to recognize as a vast migration of families out of the southwestern plains states. In the image she cradles an infant and supports two older children, who cling to her. Lange’s photo encapsulated the nation’s struggle. The subject of the photograph seemed used to hard work but down on her luck, and uncertain about what the future might hold.

The “Okies,” as such westward migrants were disparagingly called by their new neighbors, were the most visible group many who were on the move during the Depression, lured by news and rumors of jobs in far flung regions of the country. By 1932 sociologists were estimating that millions of men were on the roads and rails travelling the country. Economists sought to quantify the movement of families from the Plains. Popular magazines and newspapers were filled with stories of homeless boys and the veterans-turned-migrants of the Bonus Army commandeering boxcars. Popular culture, such as William Wellman’s 1933 film, Wild Boys of the Road, and, most famously, John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath, published in 1939 and turned into a hit movie a year later, captured the Depression’s dislocated populations.

These years witnessed the first significant reversal in the flow of people between rural and urban areas. Thousands of city-dwellers fled the jobless cities and moved to the country looking for work. As relief efforts floundered, many state and local officials threw up barriers to migration, making it difficult for newcomers to receive relief or find work. Some state legislatures made it a crime to bring poor migrants into the state and allowed local officials to deport migrants to neighboring states. In the winter of 1935-1936, California, Florida, and Colorado established “border blockades” to block poor migrants from their states and reduce competition with local residents for jobs. A billboard outside Tulsa, Oklahoma, informed potential migrants that there were “NO JOBS in California” and warned them to “KEEP Out.”

During her assignment as a photographer for the Works Progress Administration (WPA), Dorothea Lange documented the movement of migrant families forced from their homes by drought and economic depression. This family was in the process of traveling 124 miles by foot, across Oklahoma, because the father was unable to receive relief or WPA work of his own due to an illness. Dorothea Lange, “Family walking on highway, five children” (June 1938) Works Progress Administration, Library of Congress.

Sympathy for migrants, however, accelerated late in the Depression with the publication of John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath. The Joad family’s struggles drew attention to the plight of Depression-era migrants and, just a month after the nationwide release of the film version, Congress created the Select Committee to Investigate the Interstate Migration of Destitute Citizens. Starting in 1940, the Committee held widely publicized hearings. But it was too late. Within a year of its founding, defense industries were already gearing up in the wake of the outbreak of World War II, and the “problem” of migration suddenly became a lack of migrants needed to fill war industries. Such relief was nowhere to be found in the 1930s.

Americans meanwhile feared foreign workers willing to work for even lower wages. The Saturday Evening Post warned that foreign immigrants, who were “compelled to accept employment on any terms and conditions offered,” would exacerbate the economic crisis. On September 8, 1930, the Hoover administration issued a press release on the administration of immigration laws “under existing conditions of unemployment.” Hoover instructed consular officers to scrutinize carefully the visa applications of those “likely to become public charges” and suggested that this might include denying visas to most, if not all, alien laborers and artisans. The crisis itself had served to stifle foreign immigration, but such restrictive and exclusionary actions in the first years of the Depression intensified its effects. The number of European visas issued fell roughly 60 percent while deportations dramatically increased. Between 1930 and 1932, 54,000 people were deported. An additional 44,000 deportable aliens left “voluntarily.”

Exclusionary measures hit Mexican immigrants particularly hard. The State Department made a concerted effort to reduce immigration from Mexico as early as 1929 and Hoover’s executive actions arrived the following year. Officials in the Southwest led a coordinated effort to push out Mexican immigrants. In Los Angeles, the Citizens Committee on Coordination of Unemployment Relief began working closely with federal officials in early 1931 to conduct deportation raids while the Los Angeles County Department of Charities began a simultaneous drive to repatriate Mexicans and Mexican Americans on relief, negotiating a charity rate with the railroads to return Mexicans “voluntarily” to their mother country. According to the federal census, from 1930 to 1940 the Mexican-born population living in Arizona, California, New Mexico and Texas fell from 616,998 to 377,433. Franklin Roosevelt did not indulge anti-immigrant sentiment as willingly as Hoover had. Under the New Deal, the Immigration and Naturalization Service halted some of the Hoover Administration’s most divisive practices, but, with jobs suddenly scarce, hostile attitudes intensified, and official policies less than welcoming, immigration plummeted and deportations rose. Over the course of the Depression, more people left the United States than entered it.

Summary

After leaving the Dust Bowl for California, Lester Hunter wrote the poem “I’d Rather Not be on Relief,” which quickly became an anthem for Americans who had experienced the hardships of the Dust Bowl first hand. The poem captured the lived experience of the Great Depression and the plight of Dust Bowl migrants, articulating migrants’ desire “not to be on the rolls of relief,/ Or work on the W.P.A.” As Hunter’s poem indicated, migrants’ goals were modest. They wanted respect and the ability to feed and house their families. Unfortunately, for the duration of the 1930s, finding work remained a very real struggle for millions of Americans in the Great Plains states. The tide finally turned during World War II, when the defense industry was suddenly in desperate need of workers. Empathy for the environmental refugees of the Dust Bowl had started to gain ground in the 1930s, and many migrants were able to participate in the new economy of World War II and finally crawl out of the extreme poverty of the last decade. If you had lived through the Dust Bowl, what survival strategies would you have used to navigate the economy, environment, and prejudices of the era? And ultimately, what does the Dust Bowl teach us about 20th century America?