20

The growth of industry prompted an explosion in the need for industrial labor in the United States. Manufacturers grew reliant on immigrants to fill their ranks as the flood of Americans migrating from rural areas to cities was not enough to meet the demand. As industrial corporations replaced smaller (and more local) businesses, foreign policy also began to reflect a desire to ensure there was a market for American goods.

As immigrants poured into American cities, resistance grew from “old” immigrants who saw these “new” arrivals as a threat to their economic stability and cultural identify. Although the United States had no official language or religion, those who did not speak English or affiliate with Protestantism were seen as outsiders and felt considerable pressure to assimilate.

Considered the first illegal immigrants after the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, the Chinese suffered a particularly fierce wave of anti-immigrant hysteria. Likewise, other immigrant groups were demarcated as largely unacceptable given the growing demand to preserve authentic “Americanism.” The Japanese were limited by the Gentleman’s Agreement and immigrants from southern and eastern Europe were targeted by increasingly comprehensive immigration regulation. Other “outsiders,” like Catholics, wrestled with the demand for assimilation within the United States as they still felt pressure from the Pope and other faith leaders to hold fast to their beliefs and faith practices as a means to resist moral corruption.

Immigration

For Americans at the turn of the century, imperialism and immigration were two sides of the same coin. The involvement of American women with imperialist and anti-imperialist activity demonstrates how foreign policy concerns were brought home and became, in a sense, domesticated. It is also no coincidence that many of the women involved in both imperialist and anti-imperialist organizations were also very much concerned with the plight of new arrivals to the United States. Industrialization, imperialism, and immigration were all linked. Imperialism had at its core a desire for markets for American goods, and those goods were increasingly manufactured by immigrant labor. This sense of growing dependence on “others” as producers and consumers, along with doubts about their capability of assimilation into the mainstream of white, Protestant American society, caused a great deal of anxiety among native-born Americans.

Between 1870 and 1920, over twenty-five million immigrants arrived in the United States. This migration was largely a continuation of a process begun before the Civil War, though, by the turn of the twentieth century, new groups such as Italians, Poles, and Eastern European Jews made up a larger percentage of the arrivals while Irish and German numbers began to dwindle. This massive movement of people to the United States was influenced by a number of causes, or “push” and “pull” factors. In other words, certain conditions in their home countries encouraged people to leave, while other factors encouraged them to choose the United States for their destination. For example, a young husband and wife living in Sweden in the 1880s and unable to purchase farmland might read an advertisement for inexpensive land in the American Midwest and choose to sail to the United States. Or a Russian Jewish family, eager to escape brutal attacks sanctioned by the Czar, looked to the United States as a land of freedom. Or perhaps a Japanese migrant might hear of the fertile land and choose to sail for California. Thus, there were a number of factors (hunger, lack of land, military conscription, and religious persecution) that served to push people out of their home countries. Meanwhile, the United States offered a number of possibilities that made it an appealing destination for these migrants.

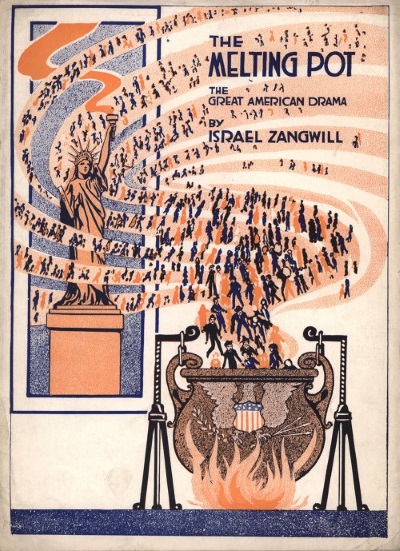

The most important factor drawing immigrants to the United States between 1880 and 1920 was the maturation of American capitalism into large industrial complexes producing goods such as steel, textiles, and food products, replacing smaller and more local workshops. The influx of immigrants, alongside a large movement of Americans from the countryside to the city, helped propel the rapid growth of cities like New York, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Milwaukee, and St. Louis. By 1890, in most large northern cities, immigrants and their children amounted to 60 percent of the population, sometimes reaching as high as 80 or 90 percent. Many immigrants, particularly those from Italy or the Balkans, hoped to return home with enough money to purchase land. But those who stayed faced many challenges. How did American immigrants adjust to their new homes? Did the new arrivals join a “melting pot” and simply become just like those people already in the United States? Or did they retain – and even strengthen – their ethnic identities, creating a more pluralistic society? The answer lies somewhere in the middle.

New immigrant groups formed vibrant societies and organizations to ease the transition to their new home. Some examples include Italian workmen’s clubs, Eastern European Jewish mutual-aid societies, and Polish Catholic churches. These organizations provided cultural space for immigrants to maintain their arts, languages, and traditions. Moreover, these organizations attracted even more immigrants. Thus new arrivals came directly to American cities where they knew they would find someone from their home country and perhaps even from their home village or family.

Although the growing United States economy needed large numbers of immigrant workers for its factories and mills, many Americans reacted negatively to the arrival of so many immigrants. Nativists opposed mass immigration for various reasons. Some felt that the new arrivals were unfit for American democracy, and that Irish or Italian immigrants used violence or bribery to corrupt municipal governments. Others (often earlier immigrants themselves) worried that the arrival of even more immigrants would result in fewer jobs and lower wages. Such fears combined and resulted in anti-Chinese protests on the West Coast in the 1870s. Still others worried that immigrants brought with them radical ideas such as socialism and communism. These fears multiplied after the Chicago Haymarket affair in 1886, in which immigrants were accused of killing police officers in a bomb blast.26

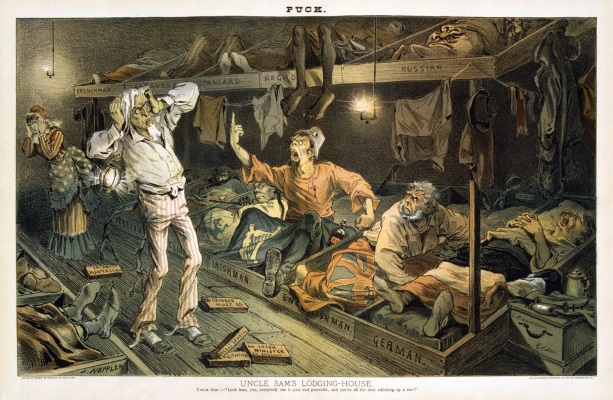

Nativist sentiment intensified in the late nineteenth century as immigrants streamed into American cities to fuel the factory boom. “Uncle Sam’s Lodging House” conveys this anti-immigrant attitude, with caricatured representations of Europeans, Asians, and African Americans creating a chaotic scene. Joseph Ferdinand Keppler, “Uncle Sam’s lodging-house,” in Puck (June 7, 1882). Wikimedia.

In September 1876, Franklin Benjamin Sanborn, a member of the Massachusetts Board of State Charities, gave an address in support of the introduction of regulatory federal immigration legislation at an interstate conference of charity officials in Saratoga, New York. Immigration might bring some benefits, but “it also introduces disease, ignorance, crime, pauperism and idleness.” Sanborn thus advocated federal action to stop “indiscriminate and unregulated immigration.”27

Sanborn’s address was aimed at restricting only the immigration of paupers from Europe to the East Coast, but the idea of immigration restrictions were common across the United States in the late nineteenth century, when many variously feared that the influx of foreigners would undermine the racial, economic, and moral integrity of American society. From the 1870s to the 1920s, the federal government passed a series of laws limiting or discontinuing the immigration of particular groups and the United States remained committed to regulating the kind of immigrants who would join American society. To critics, regulations legitimized racism, class bias, and ethnic prejudice as formal national policy.

The first move for federal immigration control came from California, where racial hostility toward Chinese immigrants had mounted since the mid-nineteenth century. In addition to accusing Chinese immigrants of racial inferiority and unfitness for American citizenship, opponents claimed that they were also economically and morally corrupting American society with cheap labor and immoral practices, such as prostitution. Immigration restriction was necessary for the “Caucasian race of California,” as one anti-Chinese politician declared, and for European Americans to “preserve and maintain their homes, their business, and their high social and moral position.” In 1875, the anti-Chinese crusade in California moved Congress to pass the Page Act, which banned the entry of convicted criminals, Asian laborers brought involuntarily, and women imported “for the purposes of prostitution,” a stricture designed chiefly to exclude Chinese women. Then, in May 1882, Congress suspended the immigration of all Chinese laborers with the Chinese Exclusion Act, making the Chinese the first immigrant group subject to admission restrictions on the basis of race. They became the first illegal immigrants. (Jacbson, Virtues.))

The idea of America as a “melting pot,” a metaphor common in today’s parlance, was a way of arguing for the ethnic assimilation of all immigrants into a nebulous “American” identity at the turn of the 20th century. A play of the same name premiered in 1908 to great acclaim, causing even the former president Theodore Roosevelt to tell the playwright, “That’s a great play, Mr. Zangwill, that’s a great play.” Cover of Theater Programme for Israel Zangwill’s play “The Melting Pot”, 1916. Wikimedia.

On the other side of the country, Atlantic seaboard states also facilitated the formation of federal immigration policy. Since the colonial period, East Coast states had regulated immigration through their own passenger laws, which prohibited the landing of destitute foreigners unless shipmasters prepaid certain amounts of money in the support of those passengers. The state-level control of pauper immigration developed into federal policy in the early 1880s. In August 1882, Congress passed the Immigration Act, denying admission to people who were not able to support themselves and those, such as paupers, people with mental illnesses, or convicted criminals, who might otherwise threaten the security of the nation.

The category of excludable people expanded continuously after 1882. In 1885, in response to American workers’ complaints about cheap immigrant labor, Congress added foreign workers migrating under labor contracts with American employers to the list of excludable people. Six years later, the federal government included people who seemed likely to become wards of the state, people with contagious diseases, and polygamists, and made all groups of excludable people deportable. In 1903, those who would pose ideological threats to American republican democracy, such as anarchists and socialists, also became the subject of new immigration restrictions.

Many immigration critics were responding the shifting demographics of American immigration. The center of immigrant-sending regions shifted from northern and western Europe to Southern and Eastern Europe and Asia. These “new immigrants” were poorer, spoke languages other than English, and were likely Catholic or Jewish. White Protestant Americans typically regarded them as inferior, and American immigration policy began to reflect more explicit prejudice than ever before. One restrictionist declared that these immigrants were “races with which the English-speaking people have never hitherto assimilated, and who are most alien to the great body of the people of the United States.” The increased immigration of people from Southern and Eastern Europe, such as Italians, Jews, Slavs, and Greeks, led directly to calls for tighter restrictive measures. In 1907, the immigration of Japanese laborers was practically suspended when the American and Japanese governments reached the so-called Gentlemen’s Agreement, according to which Japan would stop issuing passports to working-class emigrants. In its 42-volume report of 1911, the United States Immigration Commission highlighted the impossibility of incorporating these new immigrants into American society. The report highlighted their supposed innate inferiority, asserting that they were the causes of rising social problems in America, such as poverty, crime, prostitution, and political radicalism.28

The assault against immigrants’ Catholicism provides an excellent example of the challenges immigrant groups faced in the United States. By 1900, Catholicism in the United States had grown dramatically in size and diversity, from one percent of the population a century earlier to the largest religious denomination in America (though still outnumbered by Protestants as a whole). As a result, Catholics in America faced two intertwined challenges, one external, related to Protestant anti-Catholicism, and the other internal, having to do with the challenges of assimilation.

Externally, the Church and its members remained an “outsider” religion in a nation that continued to see itself as culturally and religiously Protestant. Torrents of anti-Catholic literature and scandalous rumors maligned Catholics. Many Protestants doubted whether Catholics could ever make loyal Americans because they supposedly owed primary allegiance to the Pope.

Internally, Catholics in America faced the question every immigrant group has had to answer: to what extent should they become more like native-born Americans? This question was particularly acute, as Catholics encompassed a variety of languages and customs. Beginning in the 1830s, Catholic immigration to the U.S. had exploded with the increasing arrival of Irish and German immigrants. Subsequent Catholic arrivals from Italy, Poland, and other Eastern European countries chafed at Irish dominance over the Church hierarchy. Mexican and Mexican American Catholics, whether recent immigrants or incorporated into the nation after the Mexican American War, expressed similar frustrations. Could all these different Catholics remain part of the same church?

Catholic clergy approached this situation from a variety of perspectives. Some bishops advocated rapid assimilation into the English-speaking mainstream. These “Americanists” advocated an end to “ethnic parishes”—the unofficial practice of permitting separate congregations for Poles, Italians, Germans, etc.—in the belief that such isolation only delayed immigrants’ entry into the American mainstream. They anticipated that the Catholic Church could thrive in a nation that espoused religious freedom, if only they assimilated. Meanwhile, however, more conservative clergy cautioned against assimilation. While they conceded that the U.S. had no official religion, they felt that Protestant notions of the separation of church and state and of licentious individual liberty posed a threat to the Catholic faith. They further saw ethnic parishes as an effective strategy protecting immigrant communities and worried that Protestants would use public schools to attack the Catholic faith. Eventually, the head of the Catholic Church, Pope Leo XIII, weighed in on the controversy. In 1899, he sent a special letter (an encyclical) to an archbishop in the United States. Leo reminded the Americanists that the Catholic Church was a unified global body and that American liberties did not give Catholics the freedom to alter church teachings. The Americanists denied any such intention, but the conservative clergy claimed that the Pope had sided with them. Tension between Catholicism and American life, however, would continue well into the twentieth century.29

The American encounter with Catholicism—and Catholicism’s encounter with America—testified to the tense relationship between native-born and foreign-born Americans, and to the larger ideas Americans used to situate themselves in a larger world, a world of empire and immigrants.

Attribution:

American YAWP. (n.d.) Immigration. Retrieved August 14, 2017 from http://www.americanyawp.com/text/19-american-empire/

The Changing Nature of European Immigration

Immigrants also shifted the demographics of the rapidly growing cities. Although immigration had always been a force of change in the United States, it took on a new character in the late nineteenth century. Beginning in the 1880s, the arrival of immigrants from mostly southern and eastern European countries rapidly increased while the flow from northern and western Europe remained relatively constant.

| Region Country | 1870 | 1880 | 1890 | 1900 | 1910 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern and Western Europe | 4,845,679 | 5,499,889 | 7,288,917 | 7,204,649 | 7,306,325 |

| Germany | 1,690,533 | 1,966,742 | 2,784,894 | 2,663,418 | 2,311,237 |

| Ireland | 1,855,827 | 1,854,571 | 1,871,509 | 1,615,459 | 1,352,251 |

| England | 550,924 | 662,676 | 908,141 | 840,513 | 877,719 |

| Sweden | 97,332 | 194,337 | 478,041 | 582,014 | 665,207 |

| Austria | 30,508 | 38,663 | 123,271 | 275,907 | 626,341 |

| Norway | 114,246 | 181,729 | 322,665 | 336,388 | 403,877 |

| Scotland | 140,835 | 170,136 | 242,231 | 233,524 | 261,076 |

| Southern and Eastern Europe | 93,824 | 248,620 | 728,851 | 1,674,648 | 4,500,932 |

| Italy | 17,157 | 44,230 | 182,580 | 484,027 | 1,343,125 |

| Russia | 4,644 | 35,722 | 182,644 | 423,726 | 1,184,412 |

| Poland | 14,436 | 48,557 | 147,440 | 383,407 | 937,884 |

| Hungary | 3,737 | 11,526 | 62,435 | 145,714 | 495,609 |

| Czechoslovakia | 40,289 | 85,361 | 118,106 | 156,891 | 219,214 |

The previous waves of immigrants from northern and western Europe, particularly Germany, Great Britain, and the Nordic countries, were relatively well off, arriving in the country with some funds and often moving to the newly settled western territories. In contrast, the newer immigrants from southern and eastern European countries, including Italy, Greece, and several Slavic countries including Russia, came over due to “push” and “pull” factors similar to those that influenced the African Americans arriving from the South. Many were “pushed” from their countries by a series of ongoing famines, by the need to escape religious, political, or racial persecution, or by the desire to avoid compulsory military service. They were also “pulled” by the promise of consistent, wage-earning work.

Whatever the reason, these immigrants arrived without the education and finances of the earlier waves of immigrants, and settled more readily in the port towns where they arrived, rather than setting out to seek their fortunes in the West. By 1890, over 80 percent of the population of New York would be either foreign-born or children of foreign-born parentage. Other cities saw huge spikes in foreign populations as well, though not to the same degree, due in large part to Ellis Island in New York City being the primary port of entry for most European immigrants arriving in the United States.

The number of immigrants peaked between 1900 and 1910, when over nine million people arrived in the United States. To assist in the processing and management of this massive wave of immigrants, the Bureau of Immigration in New York City, which had become the official port of entry, opened Ellis Island in 1892. Today, nearly half of all Americans have ancestors who, at some point in time, entered the country through the portal at Ellis Island. Doctors or nurses inspected the immigrants upon arrival, looking for any signs of infectious diseases (Figure). Most immigrants were admitted to the country with only a cursory glance at any other paperwork. Roughly 2 percent of the arriving immigrants were denied entry due to a medical condition or criminal history. The rest would enter the country by way of the streets of New York, many unable to speak English and totally reliant on finding those who spoke their native tongue.

This photo shows newly arrived immigrants at Ellis Island in New York. Inspectors are examining them for contagious health problems, which could require them to be sent back. (credit: NIAID)

Seeking comfort in a strange land, as well as a common language, many immigrants sought out relatives, friends, former neighbors, townspeople, and countrymen who had already settled in American cities. This led to a rise in ethnic enclaves within the larger city. Little Italy, Chinatown, and many other communities developed in which immigrant groups could find everything to remind them of home, from local language newspapers to ethnic food stores. While these enclaves provided a sense of community to their members, they added to the problems of urban congestion, particularly in the poorest slums where immigrants could afford housing.

The demographic shift at the turn of the century was later confirmed by the Dillingham Commission, created by Congress in 1907 to report on the nature of immigration in America; the commission reinforced this ethnic identification of immigrants and their simultaneous discrimination. The report put it simply: These newer immigrants looked and acted differently. They had darker skin tone, spoke languages with which most Americans were unfamiliar, and practiced unfamiliar religions, specifically Judaism and Catholicism. Even the foods they sought out at butchers and grocery stores set immigrants apart. Because of these easily identifiable differences, new immigrants became easy targets for hatred and discrimination. If jobs were hard to find, or if housing was overcrowded, it became easy to blame the immigrants. Like African Americans, immigrants in cities were blamed for the problems of the day.

Growing numbers of Americans resented the waves of new immigrants, resulting in a backlash. The Reverend Josiah Strong fueled the hatred and discrimination in his bestselling book, Our Country: Its Possible Future and Its Present Crisis, published in 1885. In a revised edition that reflected the 1890 census records, he clearly identified undesirable immigrants—those from southern and eastern European countries—as a key threat to the moral fiber of the country, and urged all good Americans to face the challenge. Several thousand Americans answered his call by forming the American Protective Association, the chief political activist group to promote legislation curbing immigration into the United States. The group successfully lobbied Congress to adopt both an English language literacy test for immigrants, which eventually passed in 1917, and the Chinese Exclusion Act (discussed in a previous chapter). The group’s political lobbying also laid the groundwork for the subsequent Emergency Quota Act of 1921 and the Immigration Act of 1924, as well as the National Origins Act.

Attribution:

The Changing Nature of European Immigration

Retrieved August 14, 2017 from

https://cnx.org/contents/p7ovuIkl@3.38:FFyiTJpy@3/The-African-American-Great-Mig

Erika Lee: Immigrant Stories

Attribution:

Erika Lee: Immigration Stories

Retreived August 14, 2017 from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wfcYY6nk_Ko

Summary

As the United States continued to grow as an industrial power, the need for labor and materials also expanded. In order to meet the demand for labor, the list of those who joined the ranks of industrial workers began to include those also labeled as undesirable. Women, blacks, and “new” immigrants were all part of the labor pool that grew to meet the needs of the industrial complex.

As America wrestled with its cultural identity, a growing demand for assimilation among immigrants took shape. Government regulation increased to protect the American way of life, including immigration restrictions. Groups such as Chinese, Japanese, and Catholics were targeted for their distinctly “anti-American” beliefs or way of life. The xenophobia that guided these restrictions emerged in a way that was both swift and powerful. The Chinese Exclusion Act passed in 1882 and the Gentleman’s Agreement of 1907 are two manifestations of the growing hysteria to keep undesirables out.

While the resistance was growing within the United States, the push factors for many immigrants ultimately forced their hand to immigrate. Scarcity of land and resources, lack of economic opportunities and over-population in some regions forced Europeans in particular to seek employment and opportunity in the United States. They settled in communities with other immigrants who spoke their language and practiced the same customs. The “Little Italy” or “Chinatown” areas within cities became easy targets for racially motivated discrimination.