4

Most modern Americans would hardly recognize the America of 1800. The United States of 1800 was an agrarian, largely rural nation, and the overwhelming majority of Americans lived and worked on farms. Although cities existed, they were almost unrecognizable by modern standards. New York City, the largest city in the nation in 1800, had a population of 60,515. Modern city services, such as garbage pickup and professional police and fire departments, largely did not exist or were run by private organizations or amateurs. And most cities had almost no modern zoning laws or transportation. The United States of 1900, in contrast, would be recognizable to almost all Americans today. The largest city in the country in 1900, New York City, had a population of 3.4 million, and was crisscrossed by electric streetcars and skyscrapers. Cities and industry had been modernized, technological innovations had transformed the economy, and the nation as a whole had become more diverse and more urban. As a result, by the 1920s the majority of Americans worked in the service industry and lived in cities, which had enormous repercussions on the character of 20th century American society. For Americans who lived through the 19th century, especially in major urban centers like Manhattan, the transformations industrialization and urbanization entailed must have been mind-boggling. America was no longer a rural, agrarian nation. By 1900, it was well on its way to becoming one of the largest industrial powers in the world.

The railroads created the first great concentrations of capital, spawned the first massive corporations, made the first of the vast fortunes that would define the “Gilded Age,” unleashed labor demands that united thousands of farmers and immigrants, and linked many towns and cities. National railroad mileage tripled in the twenty years after the outbreak of the Civil War, and tripled again over the four decades that followed. Railroads impelled the creation of uniform time zones across the country, gave industrialists access to remote markets, and opened the American west. Railroad companies were the nation’s largest businesses. Their vast national operations demanded the creation of innovative new corporate organization, advanced management techniques, and vast sums of capital. Their huge expenditures spurred countless industries and attracted droves of laborers. And as they crisscrossed the nation, they created a national market, a truly national economy, and, seemingly, a new national culture.

The railroads were not natural creations. Their vast capital requirements required the use of incorporation, a legal innovation that protected shareholders from losses. Enormous amounts of government support followed. Federal, state, and local governments offered unrivaled handouts to create the national rail networks. Lincoln’s Republican Party—which dominated government policy during the Civil War and Reconstruction—passed legislation granting vast subsidies. Hundreds of millions of acres of land and millions of dollars’ worth of government bonds were freely given to build the great transcontinental railroads and the innumerable trunk lines that quickly annihilated the vast geographic barriers that had so long sheltered American cities from one another.

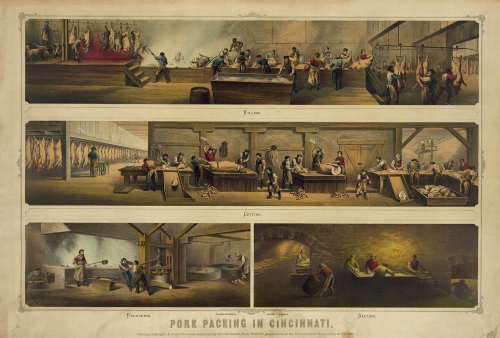

This print shows the four stages of pork packing in nineteenth-century Cincinnati.

This print shows the four stages of pork packing in nineteenth-century Cincinnati. This centralization of production made meat-packing an innovative industry, one of great interest to industrialists of all ilks. In fact, this chromo-lithograph was exhibited by the Cincinnati Pork Packers’ Association at the International Exposition in Vienna, Austria. “Pork Packing in Cincinnati,” 1873. Wikimedia.

As railroad construction drove economic development, new means of production spawned new systems of labor. Many wage earners had traditionally seen factory work as a temporary stepping-stone to attaining their own small businesses or farms. After the war, however, new technology and greater mechanization meant fewer and fewer workers could legitimately aspire to economic independence. Stronger and more organized labor unions formed to fight for a growing, more-permanent working class. At the same time, the growing scale of economic enterprises increasingly disconnected owners from their employees and day-to-day business operations. To handle their vast new operations, owners turned to managers. Educated bureaucrats swelled the ranks of an emerging middle class.

Industrialization also remade much of American life outside of the workplace. Rapidly growing industrialized cities knit together urban consumers and rural producers into a single, integrated national market. Food production and consumption, for instance, were utterly nationalized. Chicago’s Stock Yards seemingly tied it all together. Between 1866 and 1886, ranchers drove a million head of cattle annually overland from Texas ranches to railroad depots in Kansas for shipment, by rail, to Chicago. After travelling through modern “disassembly lines,” the animals left the adjoining slaughterhouses as slabs of meat to be packed into refrigerated rail cars and sent to butcher shops across the continent. By 1885, a handful of large-scale industrial meatpackers in Chicago were producing nearly 500 million pounds of “dressed” beef annually. The new scale of industrialized meat production transformed the landscape. Buffalo herds, grasslands, and old-growth forests gave way to cattle, corn, and wheat. Chicago became the Gateway City, a crossroads connecting American agricultural goods, capital markets in New York and London, and consumers from all corners of the United States.

Technological innovation accompanied economic development. For April Fool’s Day in 1878, the New York Daily Graphic published a fictitious interview with the celebrated inventor Thomas A. Edison. The piece described the “biggest invention of the age”—a new Edison machine that could create forty different kinds of food and drink out of only air, water, and dirt. “Meat will no longer be killed and vegetables no longer grown, except by savages,” Edison promised. The machine would end “famine and pauperism.” And all for $5 or $6 per machine! The story was a joke, of course, but Edison nevertheless received inquiries from readers wondering when the food machine would be ready for the market. Americans had apparently witnessed such startling technological advances—advances that would have seemed far-fetched mere years earlier—that the Edison food machine seemed entirely plausible.

In September 1878, Edison announced a new and ambitious line of research and development—electric power and lighting. The scientific principles behind dynamos and electric motors—the conversion of mechanical energy to electrical power, and vice versa—were long known, but Edison applied the age’s bureaucratic and commercial ethos to the problem. Far from a lone inventor gripped by inspiration toiling in isolation, Edison advanced the model of commercially minded management of research and development. Edison folded his two identities, business manager and inventor, together. He called his Menlo Park research laboratory an “invention factory” and promised to turn out “a minor invention every ten days and a big thing every six months or so.” He brought his fully equipped Menlo Park research laboratory and the skilled machinists and scientists he employed to bear on the problem of building an electric power system—and commercializing it.

By late fall 1879, Edison exhibited his system of power generation and electrical light for reporters and investors. Then he scaled up production. He sold generators to businesses. By the middle of 1883, Edison had overseen construction of 330 plants powering over 60,000 lamps in factories, offices, printing houses, hotels, and theaters around the world. He worked on municipal officials to build central power stations and run power lines. New York’s Pearl Street central station opened in September 1882 and powered a square-mile of downtown Manhattan. Electricity revolutionized the world. It not only illuminated the night, it powered the second industrial revolution. Factories could operate anywhere at any hour. Electric rail cars allowed for cities to build out and electric elevators allowed for them to build up.

Economic advances, technological innovation, social and cultural evolution, demographic transformations: the United States was a nation transformed. Industry boosted productivity, railroads connected the nation, more and more Americans labored for wages, new bureaucratic occupations created a vast “white collar” middle class, and unprecedented fortunes rewarded the owners of capital. These revolutionary changes, of course, would not occur without conflict or consequence, but they demonstrated the profound transformations remaking the nation. Change was not confined to economics alone. Change gripped the lives of everyday Americans and fundamentally reshaped American culture.

Attribution:

Life in Industrial America. (n.d.). In The American Yawp. Retrieved September 9, 2017, from http://www.americanyawp.com/text/18-industrial-america/

Immigration and Urbanization

Industry pulled ever more Americans into cities. Manufacturing needed the labor pool and the infrastructure. America’s urban population increased seven fold in the half-century after the Civil War. Soon the United States had more large cities than any country in the world. The 1920 U.S. census revealed that, for the first time, a majority of Americans lived in urban areas. Much of that urban growth came from the millions of immigrants pouring into the nation. Between 1870 and 1920, over 25 million immigrants arrived in the United States.

By the turn of the twentieth century, new immigrant groups such as Italians, Poles, and Eastern European Jews made up a larger percentages of arrivals than the Irish and Germans. The specific reasons that immigrants left their particular countries and the reasons they came to the United States (what historians call “push” and “pull” factors) varied. For example, a young husband and wife living in Sweden in the 1880s and unable to purchase farmland might read an advertisement for inexpensive land in the American Midwest and immigrate to the United States to begin a new life. A young Italian man might simply hope to labor in a steel factory long enough to save up enough money to return home and purchase land for a family. A Russian Jewish family, persecuted in European pogroms, might look to the United States as a sanctuary. Or perhaps a Japanese migrant might hear of fertile farming land on the West Coast and choose to sail for California. But if many factors pushed people away from their home countries, by far the most important factor drawing immigrants was economics. Immigrants came to the United States looking for work.

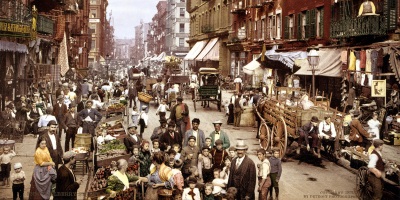

Factories in New York, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Milwaukee, and St. Louis attracted large numbers of immigrants. By 1890, immigrants and their children accounted for roughly 60 percent of the population in most large northern cities (and could reach as high as 80 or 90 percent). Many immigrants, especially from Italy and the Balkans, always intended to return home. But what about those who stayed? Did the new arrivals assimilate together in the American “melting pot”—becoming just like those already in the United States—or did they retain—and sometimes even strengthen—their traditional ethnic identities? The answer lies somewhere in between. Immigrants from specific countries—and often even specific communities—often clustered together in ethnic neighborhoods. They formed vibrant organizations and societies, such as Italian workmen’s clubs, Eastern European Jewish mutual-aid societies, and Polish Catholic Churches, to ease the transition to their new American home. Immigrant communities published newspapers in dozens of languages and purchased spaces to maintain their arts, languages, and traditions alive. And from these foundations they facilitated even more immigration: after staking out a claim to some corner of American life, they wrote home and encouraged others to follow them (historians call this “chain migration”).

Many city’s politics adapted to immigrant populations. The infamous urban political “machines” often operated as a kind of mutual aid society. New York City’s Democratic Party machine, popularly known as Tammany Hall, drew the greatest ire from critics and seemed to embody all of the worst of city machines, but it also responded to immigrant needs. In 1903, journalist William Riordon published a book, Plunkitt of Tammany Hall, which chronicled the activities of ward heeler George Washington Plunkitt. Plunkitt elaborately explained to Riordon the difference between “honest graft” and “dishonest graft:” “I made my pile in politics, but, at the same time, I served the organization and got more big improvements for New York City than any other livin’ man.” While exposing corruption, Riordon also revealed the hard work Plunkitt undertook on behalf of his largely immigrant constituency. On a typical day, Riordon wrote, Plunkitt was awakened at 2:00 AM to bail out a saloon-keeper who stayed open too late, was awakened again at 6:00 AM because of a fire in the neighborhood and spent time finding lodgings for the families displaced by the fire, and, after spending the rest of the morning in court to secure the release of several of his constituents, found jobs for four unemployed men, attended an Italian funeral, visited a church social, and dropped in on a Jewish wedding. He returned home at midnight.

Tammany Hall’s corruption, especially under the reign of William “Boss” Tweed, was legendary, but the public works projects that funded Tammany Hall’s graft also provided essential infrastructure and public services for the city’s rapidly expanding population. Water, sewer, and gas lines; schools, hospitals, civic buildings, and museums; police and fire departments; roads, parks (notably Central Park), and bridges (notably the Brooklyn Bridge): all could, in whole or in part, be credited to Tammany’s reign. Still, machine politics could never be enough. As the urban population exploded, many immigrants found themselves trapped in crowded, crime-ridden slums. Americans would eventually take notice of this “urban crisis” and propose municipal reforms, but Americans also grew concerned about the declining quality of life in rural areas.

While cities boomed, rural worlds languished. Some Americans scoffed at rural backwardness and reveled in the countryside’s decay, but many romanticized the countryside, celebrated rural life, and wondered what had been lost in the cities. Sociologist Kenyon Butterfield, concerned by the sprawling nature of industrial cities and suburbs, regretted the eroding social position of rural citizens and farmers: “agriculture does not hold the same relative rank among our industries that it did in former years.” Butterfield saw “the farm problem” as part of “the whole question of democratic civilization.” He and many others thought the rise of the cities and the fall of the countryside threatened traditional American values. Many proposed conservation. Liberty Hyde Bailey, a botanist and rural scholar selected by Theodore Roosevelt to chair a federal Commission on Country Life in 1907, believed that rural places and industrial cities were linked: “every agricultural question is a city question.”

Many longed for a middle path between the cities and the country. New suburban communities on the outskirts of American cities defined themselves in opposition to urban crowding. Americans contemplated the complicated relationships between rural places, suburban living, and urban spaces. Los Angeles became a model for the suburban development of rural places. Dana Barlett, a social reformer in Los Angeles, noted that the city, stretching across dozens of small towns, was “a better city” because of its residential identity as a “city of homes.” This language was seized upon by many suburbs who hoped to avoid both urban sprawl and rural decay. In one of these small towns on the outskirts of Los Angeles, Glendora, local leaders were “loath as anyone to see it become cosmopolitan.” Instead, in order to have Glendora “grow along the lines necessary to have it remain an enjoyable city of homes,” they needed to “bestir ourselves to direct its growth” by encouraging not industry or agriculture but residential development.

Attribution:

Life in Industrial America. (n.d.). In The American Yawp. Retrieved September 9, 2017, from http://www.americanyawp.com/text/18-industrial-america/

Summary

Industrialization and urbanization ushered many transformations into American life, but perhaps most significantly, they were ultimately responsible for drawing a sharp political and cultural divide between rural and urban spaces, pulling large numbers of immigrants into American cities, and fostering new attitudes about class into American society. Industrialization and urbanization paved the way for the Gilded Age and all of its’ benefits and shortcomings. Without industrialization and urbanization, the United States would not have become a superpower on the world stage or one of the major centers of global technological innovation. But industrialization and urbanization also promoted monopolization, extreme class inequality, and drawn-out battles between laborers and factory owners that would become a regular feature of American life until after World War I. As the nation shifted from a country of producers to a country of consumers, American values also changed, and a new emphasis was placed on Americans’ leisure time. Freed from the daily grind and responsibilities of rural life, millions of Americans began harboring broader expectations of their professional and personal life in the late 19th and early 20th century, and through unionization and other worker organizations, they increasingly began putting new demands on their employers to improve working conditions.

In large part, the modern city and work environment of the 21st century were born out of the debates about the city and workers’ rights in the 19th and early 20th centuries. What do you think the United States would look like today if industrialization and urbanization had never occurred?