35

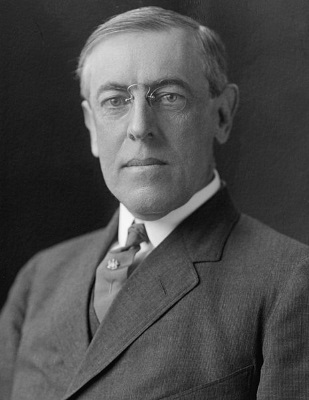

Before the United States even entered World War I, President Woodrow Wilson had a vision for the post-war world. In a speech to Congress in January of 1917, Wilson called for “peace without victory.” Wilson argued that the war must be ended without a victor or a loser so that neither side could impose terms on the other that could ultimately lead to future tensions. He believed that only a peace between equals would allow for a peaceful future. Not surprisingly, this idea was not well received by those at war. England did not want to be put on the same moral ground as Germany. And a war ravaged France had no desire to end the war without victory and the spoils that would include. By April of 1917, the US declared war on Germany and entered the fight that would last until November 11, 1918.

By the time Germany and its allies declared an armistice in November of 1918, Wilson had already been hard at work designing a plan for peace. The “Fourteen Points” as they came to be called, outlined future global diplomacy, free trade, the reduction of arms, and dealt with territorial claims and colonial empires. Wilson took this outline for postwar peace with him to the Paris Peace Conference in December of 1918. Although the Treaty of Versailles did not include many of Wilson’s Fourteen Points, it did include his League of Nations. This League would join nations together as equals for future diplomatic negotiations and military alliances. The goal of the League was to stop any future conflicts before they escalated to war.

While the other nations agreed to the Treaty that included Wilson’s League of Nations, Wilson struggled to get his own Congress to ratify the Treaty because of the League of Nations. The isolationism that had kept the United States out of World War I until 1917 reemerged in an effort to keep the United States from being entangled with European affairs in the aftermath of war.

The Battle For Peace

While Wilson had been loath to involve the United States in the war, he saw the country’s eventual participation as justification for America’s involvement in developing a moral foreign policy for the entire world. The “new world order” he wished to create from the outset of his presidency was now within his grasp. The United States emerged from the war as the predominant world power. Wilson sought to capitalize on that influence and impose his moral foreign policy on all the nations of the world.

As early as January 1918—a full five months before U.S. military forces fired their first shot in the war, and eleven months before the actual armistice—Wilson announced his postwar peace plan before a joint session of Congress. Referring to what became known as the Fourteen Points, Wilson called for openness in all matters of diplomacy and trade, specifically, free trade, freedom of the seas, an end to secret treaties and negotiations, promotion of self-determination of all nations, and more. In addition, he called for the creation of a League of Nations to promote the new world order and preserve territorial integrity through open discussions in place of intimidation and war.

As the war concluded, Wilson announced, to the surprise of many, that he would attend the Paris Peace Conference himself, rather than ceding to the tradition of sending professional diplomats to represent the country (Figure). His decision influenced other nations to follow suit, and the Paris conference became the largest meeting of world leaders to date in history. For six months, beginning in December 1918, Wilson remained in Paris to personally conduct peace negotiations. Although the French public greeted Wilson with overwhelming enthusiasm, other delegates at the conference had deep misgivings about the American president’s plans for a “peace without victory.” Specifically, Great Britain, France, and Italy sought to obtain some measure of revenge against Germany for drawing them into the war, to secure themselves against possible future aggressions from that nation, and also to maintain or even strengthen their own colonial possessions. Great Britain and France in particular sought substantial monetary reparations, as well as territorial gains, at Germany’s expense. Japan also desired concessions in Asia, whereas Italy sought new territory in Europe. Finally, the threat posed by a Bolshevik Russia under Vladimir Lenin, and more importantly, the danger of revolutions elsewhere, further spurred on these allies to use the treaty negotiations to expand their territories and secure their strategic interests, rather than strive towards world peace.

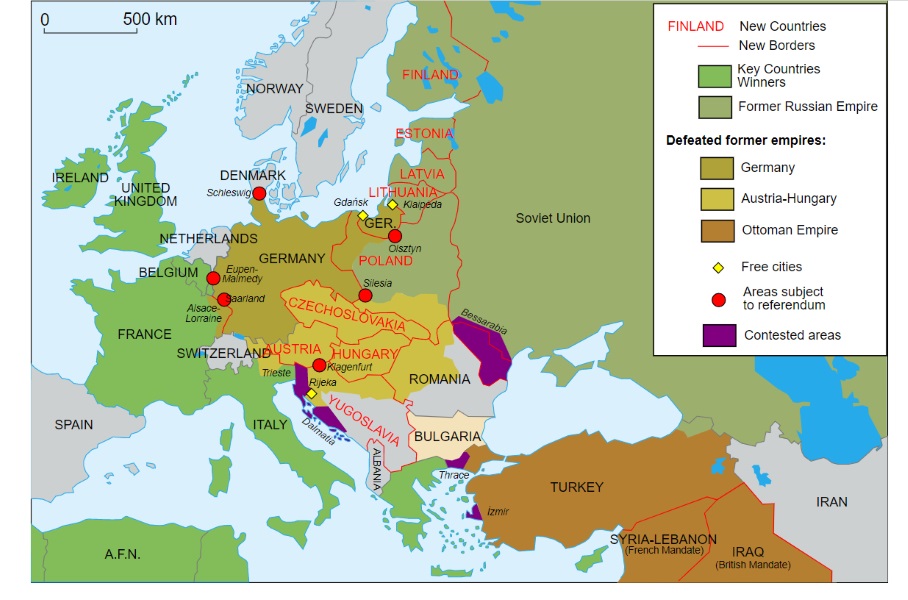

In the end, the Treaty of Versailles that officially concluded World War I resembled little of Wilson’s original Fourteen Points. The Japanese, French, and British succeeded in carving up many of Germany’s colonial holdings in Africa and Asia. The dissolution of the Ottoman Empire created new nations under the quasi-colonial rule of France and Great Britain, such as Iraq and Palestine. France gained much of the disputed territory. Great Britain led the charge that resulted in Germany agreeing to pay reparations in excess of $33 billion to the Allies. As for Bolshevik Russia, Wilson had agreed to send American troops to their northern region to protect Allied supplies and holdings there, while also participating in an economic blockade designed to undermine Lenin’s power. This move would ultimately have the opposite effect of galvanizing popular support for the Bolsheviks.

The sole piece of the original Fourteen Points that Wilson successfully fought to keep intact was the creation of a League of Nations. At a covenant agreed to at the conference, all member nations in the League would agree to defend all other member nations against military threats. Known as Article X, this agreement would basically render each nation equal in terms of power, as no member nation would be able to use its military might against a weaker member nation. Ironically, this article would prove to be the undoing of Wilson’s dream of a new world order.

Ratification of the Treaty of Versailles

Although the other nations agreed to the final terms of the Treaty of Versailles, Wilson’s greatest battle lay in the ratification debate that awaited him upon his return. As with all treaties, this one would require two-thirds approval by the U.S. Senate for final ratification, something Wilson knew would be difficult to achieve. Even before Wilson’s return to Washington, Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee that oversaw ratification proceedings, issued a list of fourteen reservations he had regarding the treaty, most of which centered on the creation of a League of Nations. An isolationist in foreign policy issues, Lodge feared that Article X would require extensive American intervention, as more countries would seek her protection in all controversial affairs. But on the other side of the political spectrum, interventionists argued that Article X would impede the United States from using her rightfully attained military power to secure and protect America’s international interests.

Wilson’s greatest fight was with the Senate, where most Republicans opposed the treaty due to the clauses surrounding the creation of the League of Nations. Some Republicans, known as Irreconcilables, opposed the treaty on all grounds, whereas others, called Reservationists, would support the treaty if sufficient amendments were introduced that could eliminate Article X. In an effort to turn public support into a weapon against those in opposition, Wilson embarked on a cross-country railway speaking tour. He began travelling in September 1919, and the grueling pace, after the stress of the six months in Paris, proved too much. Wilson fainted following a public event on September 25, 1919, and immediately returned to Washington. There he suffered a debilitating stroke, leaving his second wife Edith Wilson in charge as de facto president for a period of about six months.

Frustrated that his dream of a new world order was slipping away—a frustration that was compounded by the fact that, now an invalid, he was unable to speak his own thoughts coherently—Wilson urged Democrats in the Senate to reject any effort to compromise on the treaty. As a result, Congress voted on, and defeated, the originally worded treaty in November. When the treaty was introduced with “reservations,” or amendments, in March 1920, it again fell short of the necessary margin for ratification. As a result, the United States never became an official signatory of the Treaty of Versailles. Nor did the country join the League of Nations, which shattered the international authority and significance of the organization. Although Wilson received the Nobel Peace Prize in October 1919 for his efforts to create a model of world peace, he remained personally embarrassed and angry at his country’s refusal to be a part of that model. As a result of its rejection of the treaty, the United States technically remained at war with Germany until July 21, 1921, when it formally came to a close with Congress’s quiet passage of the Knox-Porter Resolution.

American involvement in World War I came late. Compared to the incredible carnage endured by Europe, the United States’ battles were brief and successful, although the appalling fighting conditions and significant casualties made it feel otherwise to Americans, both at war and at home. For Wilson, victory in the fields of France was not followed by triumphs in Versailles or Washington, DC, where his vision of a new world order was summarily rejected by his allied counterparts and then by the U.S. Congress. Wilson had hoped that America’s political influence could steer the world to a place of more open and tempered international negotiations. His influence did lead to the creation of the League of Nations, but concerns at home impeded the process so completely that the United States never signed the treaty that Wilson worked so hard to create.

Attribution:

OpenStax, U.S. History. OpenStax CNX. Jul 27, 2017 http://cnx.org/contents/a7ba2fb8-8925-4987-b182-5f4429d48daa@3.84.

Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points

Gentlemen of the Congress:

Once more, as repeatedly before, the spokesmen of the Central Empires have indicated their desire to discuss the objects of the war and the possible basis of a general peace. Parleys have been in progress at Brest-Litovsk between Russian representatives and representatives of the Central Powers to which the attention of all the belligerents has been invited for the purpose of ascertaining whether it may be possible to extend these parleys into a general conference with regard to terms of peace and settlement.

The Russian representatives presented not only a perfectly definite statement of the principles upon which they would be willing to conclude peace, but also an equally definite program of the concrete application of those principles. The representatives of the Central Powers, on their part, presented an outline of settlement which, if much less definite, seemed susceptible of liberal interpretation until their specific program of practical terms was added. That program proposed no concessions at all, either to the sovereignty of Russia or to the preferences of the populations with whose fortunes it dealt, but meant, in a word, that the Central Empires were to keep every foot of territory their armed forces had occupied–every province, every city, every point of vantage as a permanent addition to their territories and their power.

It is a reasonable conjecture that the general principles of settlement which they at first suggested originated with the more liberal statesmen of Germany and Austria, the men who have begun to feel the force of their own peoples’ thought and purpose, while the concrete terms of actual settlement came from the military leaders who have no thought but to keep what they have got. The negotiations have been broken off. The Russian representatives were sincere and in earnest. They cannot entertain such proposals of conquest and domination.

The whole incident is full of significance. It is also full of perplexity. With whom are the Russian representatives dealing? For whom are the representatives of the Central Empires speaking? Are they speaking for the majorities of their respective parliaments or for the minority parties, that military and imperialistic minority which has so far dominated their whole policy and controlled the affairs of Turkey and of the Balkan States which have felt obliged to become their associates in this war?

The Russian representatives have insisted, very justly, very wisely, and in the true spirit of modern democracy, that the conferences they have been holding with the Teutonic and Turkish statesmen should be held within open, not closed, doors, and all the world lies been audience, as was desired. To whom have we been listening, then? To those who speak the spirit and intention of the resolutions of the German Reichstag of the 9th of July last, the spirit and intention of the liberal leaders and parties of Germany, or to those who resist and defy that spirit and intention and insist upon conquest and subjugation? Or are we listening, in fact, to both, unreconciled and in open and hopeless contradiction? These are very serious and pregnant questions. Upon the answer to them depends the peace of the world.

But whatever the results of the parleys at Brest-Litovsk, whatever the confusions of counsel and of purpose in the utterances of the spokesmen of the Central Empires, they have again attempted to acquaint the world with their objects in the war and have again challenged their adversaries to say what their objects are and what sort of settlement they would deem just and satisfactory. There is no good reason why that challenge should not be responded to, and responded to with the utmost candor. We did not wait for it. Not once, but again and again we have laid our whole thought and purpose before the world, not in general terms only, but each time with sufficient definition to make it clear what sort of definite terms of settlement must necessarily spring out of them. Within the last week Mr. Lloyd George has spoken with admirable candor and in admirable spirit for the people and Government of Great Britain.

There is no confusion of counsel among the adversaries of the Central Powers, no uncertainty of principle, no vagueness of detail. The only secrecy of counsel, the only lack of fearless frankness, the only failure to make definite statement of the objects of the war, lies with Germany and her allies. The issues of life and death hang upon these definitions. No statesman who has the least conception of his responsibility ought for a moment to permit himself to continue this tragical and appalling outpouring of blood and treasure unless he is sure beyond a peradventure that the objects of the vital sacrifice are part and parcel of the very life of society and that the people for whom he speaks think them right and imperative as he does.

There is, moreover, a voice calling for these definitions of principle and of purpose which is, it seems to me, more thrilling and more compelling than any of the many moving voices with which the troubled air of the world is filled. It is the voice of the Russian people. They are prostrate and all but helpless, it would seem, before the grim power of Germany, which has hitherto known no relenting and no pity. Their power, apparently, is shattered. And yet their soul is not subservient. They will not yield either in principle or in action. Their conception of what is right, of what is humane and honorable for them to accept, has been stated with a frankness, a largeness of view, a generosity of spirit, and a universal human sympathy which must challenge the admiration of every friend of mankind; and they have refused to compound their ideals or desert others that they themselves may be safe.

They call to us to say what it is that we desire, in what, if in anything, our purpose and our spirit differ from theirs; and I believe that the people of the United States would wish me to respond, with utter simplicity and frankness. Whether their present leaders believe it or not, it is our heartfelt desire and hope that some way may be opened whereby we may be privileged to assist the people of Russia to attain their utmost hope of liberty and ordered peace.

It will be our wish and purpose that the processes of peace, when they are begun, shall be absolutely open and that they shall involve and permit henceforth no secret understandings of any kind. The day of conquest and aggrandizement is gone by; so is also the day of secret covenants entered into in the interest of particular governments and likely at some unlooked-for moment to upset the peace of the world. It is this happy fact, now clear to the view of every public man whose thoughts do not still linger in an age that is dead and gone, which makes it possible for every nation whose purposes are consistent with justice and the peace of the world to avow now or at any other time the objects it has in view.

We entered this war because violations of right had occurred which touched us to the quick and made the life of our own people impossible unless they were corrected and the world secured once for all against their recurrence.

What we demand in this war, therefore, is nothing peculiar to ourselves. It is that the world be made fit and safe to live in; and particularly that it be made safe for every peace-loving nation which, like our own, wishes to live its own life, determine its own institutions, be assured of justice and fair dealing by the other peoples of the world, as against force and selfish aggression.

All the peoples of the world are in effect partners in this interest, and for our own part we see very clearly that unless justice be done to others it will not be done to us.

The program of the world’s peace, therefore, is our program; and that program, the only possible program, all we see it, is this:

-

- Open covenants of peace must be arrived at, after which there will surely be no private international action or rulings of any kind, but diplomacy shall proceed always frankly and in the public view.

- Absolute freedom of navigation upon the seas, outside territorial waters, alike in peace and in war, except as the seas may be closed in whole or in part by international action for the enforcement of international covenants.

- The removal, so far as possible, of all economic barriers and the establishment of an equality of trade conditions among all the nations consenting to the peace and associating themselves for its maintenance.

- Adequate guarantees given and taken that national armaments will be reduced to the lowest points consistent with domestic safety.

- A free, open-minded, and absolutely impartial adjustment of all colonial claims, based upon a strict observance of the principle that in determining all such questions of sovereignty the interests of the population concerned must have equal weight with the equitable claims of the government whose title is to be determined.

- The evacuation of all Russian territory and such a settlement of all questions affecting Russia as will secure the best and freest cooperation of the other nations of the world in obtaining for her an unhampered and unembarrassed opportunity for the independent determination of her own political development and national policy, and assure her of a sincere welcome into the society of free nations under institutions of her own choosing; and, more than a welcome, assistance also of every kind that she may need and may herself desire. The treatment accorded Russia by her sister nations in the months to come will be the acid test of their good will, of their comprehension of her needs as distinguished from their own interests, and of their intelligent and unselfish sympathy.

- Belgium, the whole world will agree, must be evacuated and restored, without any attempt to limit the sovereignty which she enjoys in common with all other free nations. No other single act will serve as this will serve to restore confidence among the nations in the laws which they have themselves set and determined for the government of their relations with one another. Without this healing act the whole structure and validity of international law is forever impaired.

- All French territory should be freed and the invaded portions restored, and the wrong done to France by Prussia in 1871 in the matter of Alsace-Lorraine, which has unsettled the peace of the world for nearly fifty years, should be righted, in order that peace may once more be made secure in the interest of all.

- A re-adjustment of the frontiers of Italy should be effected along clearly recognizable lines of nationality.

- The peoples of Austria-Hungary, whose place among the nations we wish to see safeguarded and assured, should be accorded the freest opportunity of autonomous development.

- Romania, Serbia, and Montenegro should be evacuated; occupied territories restored; Serbia accorded free and secure access to the sea; and the relations of the several Balkan states to one another determined by friendly counsel along historically established lines of allegiance and nationality; and international guarantees of the political and economic independence and territorial integrity of the several Balkan states should be entered into.

- The Turkish portions of the present Ottoman Empire should be assured a secure sovereignty, but the other nationalities which are now under Turkish rule should be assured an undoubted security of life and an absolutely unmolested opportunity of autonomous development, and the Dardanelles should be permanently opened as a free passage to the ships and commerce of all nations under international guarantees.

- An independent Polish state should be erected which should include the territories inhabited by indisputably Polish populations, which should be assured a free and secure access to the sea, and whose political and economic independence and territorial integrity should be guaranteed by international covenant.

- 1A general association of nations must be formed under specific covenants for the purpose of affording mutual guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity to great and small states alike.

In regard to these essential rectifications of wrong and assertions of right, we feel ourselves to be intimate partners of all the governments and peoples associated together against the imperialists. We cannot be separated in interest or divided in purpose. We stand together until the end.

For such arrangements and covenants we are willing to fight and to continue to fight until they are achieved; but only because we wish the right to prevail and desire a just and stable peace such as can be secured only by removing the chief provocations to war, which this program does remove.

We have no jealousy of German greatness, and there is nothing in this program that impairs it. We grudge her no achievement or distinction of learning or of pacific enterprise such as have made her record very bright and very enviable. We do not wish to injure her or to block in any way her legitimate influence or power. We do not wish to fight her either with arms or with hostile arrangements of trade, if she is willing to associate herself with us and the other peace-loving nations of the world in covenants of justice and law and fair dealing.

We wish her only to accept a place of equality among the peoples of the world–the new world in which we now live–instead of a place of mastery.

Neither do we presume to suggest to her any alteration or modification of her institutions. But it is necessary, we must frankly say, and necessary as a preliminary to any intelligent dealings with her on our part, that we should know whom her spokesmen speak for when they speak to us, whether for the Reichstag majority or for the military party and the men whose creed is imperial domination.

We have spoken now, surely, in terms too concrete to admit of any further doubt or question. An evident principle runs through the whole program I have outlined. It is the principle of justice to all peoples and nationalities, and their right to live on equal terms of liberty and safety with one another, whether they be strong or weak.

Unless this principle be made its foundation, no part of the structure of international justice can stand. The people of the United States could act upon no other principle, and to the vindication of this principle they are ready to devote their lives, their honor, and everything that they possess. The moral climax of this, the culminating and final war for human liberty has come, and they are ready to put their own strength, their own highest purpose, their own integrity and devotion to the test.

Attribution:

Woodrow Wilson (January 8, 1918). Fourteen Points. Retrieved August 6, 2017 from https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Fourteen_Points_Speech

World War I’s Domestic Legacy

Watch from beginning to 5:05.

Attribution:

Saylor Academy. (July 21, 2011). Saylor.org HIST212: “World War I’s Domestic Legacy.” [Video File] Retrieved From: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IVjKIsHvQGs

Summary

American involvement in World War I came late. And compared to the incredible carnage European nations endured, the United States’ battles were brief and successful. However, the heinous fighting conditions and significant casualties made it feel otherwise to Americans who fought in Europe and those at home. The experience of war made many Americans wary of continued involvement in European affairs.

The Treaty of Versailles that ended World War I redrew the map of Europe and solidified tensions between powers that would fester over the next decade. President Woodrow Wilson played a significant role in the peace negotiations in an effort to lay the foundation for a peaceful postwar world. However, when he returned home with this peace that included his vision of a cooperative League of Nations, his vision of a new world order was rejected by the United States Congress.

Wilson had hoped that through joining the League of Nations, the United States would be able to use its political influence to steer the world towards more open and equal international diplomatic negotiations. However, the reticence to get involved in European affairs that had existed prior to the war reemerged in its aftermath. Concerns that membership in the League of Nations would draw the United States into continual intervention in European disputes dashed Wilson’s hopes for America to use its influence to help maintain world peace. Ultimately, the United States never signed the treaty that Wilson had worked so hard to create.