12

During World War II, the United States developed an uneasy alliance with the Soviet Union. The alliance was largely born out of the United States and Soviet Union’s shared interest in defeating the Axis Powers, particularly Nazi Germany in Europe and the Empire of Japan in Asia. In the last year of World War II, however, cracks began to emerge in America’s alliance with the Soviet Union. When it became clear that the Allied Powers would win World War II, the United States and the Soviet Union began to focus on how they could influence the postwar world. The Soviet Union wanted to create a buffer zone of Communist satellite states that separated their nation from the politics and military conflict of Europe. The United States, on the other hand, wanted to create democratic states in postwar Europe that shared America’s democratic values. These two visions of postwar Europe were so different that they simply could not coexist.

After the United States dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6th and August 9th, 1945, World War II quickly ended and the world, and especially the Allied Powers, breathed a collective sigh of relief. After 6 years of war and over 70 million casualties, world peace had finally arrived. But World War II had sewn the seeds of the next great international conflict, the Cold War, which grew out of the United States and Soviet Union’s distinct visions for the postwar world. In 1946, a civil war in Greece brought tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union to a head, and after the Soviet Union detonated their first atomic bomb in 1949, the Cold War began in earnest. Anxiety about nuclear war would dominate American society for the next decade and a half, and the Cold War would play a profound role in shaping international politics and U.S. foreign policy until the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991.

Peace and the Cold War

Relations between the United States and the Soviet Union–erstwhile allies–soured soon after the Second World War. On February 22, 1946, less than a year after the end of the war, the Charge d’Affaires of the U.S. Embassy in Moscow, George Kennan, frustrated that the Truman Administration still officially sought U.S.-Soviet cooperation, sent a famously lengthy telegram–literally referred to as the “Long Telegram”–to the State Department denouncing the Soviet Union. “World communism is like a malignant parasite which feeds only on diseased tissue,” he wrote, and “the steady advance of uneasy Russian nationalism … in [the] new guise of international Marxism … is more dangerous and insidious than ever before.”1 There could be no cooperation between the United States and the Soviet Union, Kennan wrote. Instead, the Soviets had to be “contained.” Less than two weeks later, on March 5, former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill visited President Harry Truman in his home state of Missouri and declared that Europe had been cut in half, divided by an “iron curtain” that had “descended across the Continent.”2Aggressive anti-Soviet sentiment seized the American government and soon the American people.3

The Cold War was a global political and ideological struggle between capitalist and communist countries, particularly between the two surviving superpowers of the postwar world: the United States and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). “Cold” because it was never a “hot,” direct shooting war between the United States and the Soviet Union, the generations-long, multifaceted rivalry nevertheless bent the world to its whims. Tensions ran highest, perhaps, during the “first Cold War,” which lasted from the mid-1940s through the mid-1960s, after which followed a period of relaxed tensions and increased communication and cooperation, known by the French term détente, until the “second Cold War” interceded from roughly 1979 until the collapse of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. The Cold War reshaped the world, and in so doing forever altered American life and the generations of Americans that lived within its shadow.

Political, Economic, and Military Dimensions

For starters, the following video presents a primary source that highlights how nuclear war was depicted in the 1950s: https://archive.org/details/DuckandC1951

The following resource also offers an overview of the history and build-up of the Cold War: https://cnx.org/contents/p7ovuIkl@3.84:UTh67V_v@4/The-Cold-War

The Cold War grew out of a failure to achieve a durable settlement among leaders from the “Big Three” Allies—the US, Britain, and the Soviet Union—as they met at Yalta in Russian Crimea and at Potsdam in occupied Germany to shape the postwar order. The Germans had pillaged their way across Eastern Europe and the Soviets had pillaged their way back across it at the cost of millions of lives. Stalin considered the newly conquered territory part of a Soviet “sphere of influence.” With Germany’s defeat imminent, the Allies set terms for unconditional surrender, while deliberating over reparations, tribunals, and the nature of an occupation regime that would initially be divided into American, British, French, and Soviet zones. Even as plans were made to end the fighting in the Pacific, and it was determined that the Soviets would declare war on Japan within ninety days of Germany’s surrender, suspicion and mistrust were already mounting. The political landscape was altered drastically by Franklin Roosevelt’s sudden death in April 1945, just days before the inaugural meeting of the United Nations (UN). Although Roosevelt was skeptical of Stalin, he always held out hope that the Soviets could be brought into the “Free World.” Truman, like Churchill, had no such illusions. He committed the United States to a hard-line, anti-Soviet approach.4

At the Potsdam Conference, held on the outskirts of Berlin from mid-July to early August, the allies debated the fate of Soviet-occupied Poland. Toward the end of the meeting, the American delegation received word that Manhattan Project scientists had successfully tested an atomic bomb. On July 24, when Truman told Stalin about this “new weapon of unusual destructive force,” the Soviet leader simply nodded his acknowledgement and said that he hoped the Americans would make “good use” of it.5

The Cold War had long roots. An alliance of convenience during World War II to bring down Hitler’s Germany was not enough to erase decades of mutual suspicions. The Bolshevik Revolution had overthrown the Russian Tsarists during World War I. Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin urged an immediate worldwide peace that would pave the way for world socialism just as Woodrow Wilson brought the United States into the war with promises of global democracy and free trade. The United States had intervened militarily against the Red Army during the Russian civil war, and when the Soviet Union was founded in 1922 the United States refused to recognize it. The two powers were brought together only by their common enemy, and, without that common enemy, there was little hope for cooperation.6

On the eve of American involvement in World War II, on August 14, 1941, Roosevelt and Churchill had issued a joint declaration of goals for postwar peace, known as the Atlantic Charter. An adaptation of Wilson’s Fourteen Points, the Atlantic Charter established the creation of the United Nations. The Soviet Union was among the fifty charter UN member-states and was given one of five seats—alongside the US, Britain, France, and China—on the select Security Council. The Atlantic Charter, though, also set in motion the planning for a reorganized global economy. The July 1944 United Nations Financial and Monetary Conference, more popularly known as the Bretton Woods Conference, created the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the forerunner of the World Bank, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD). The “Bretton Woods system” was bolstered in 1947 with the addition of the General Agreements on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), forerunner of the World Trade Organization (WTO). The Soviets rejected it all.

Many officials on both sides knew that the Soviet-American relationship would dissolve into renewed hostility upon the closing of the war, and events proved them right. In 1946 alone, the Soviet Union refused to cede parts of occupied Iran, a Soviet defector betrayed a Soviet spy who had worked on the Manhattan Project, and the U.S. refused Soviet calls to dismantle its nuclear arsenal. In a 1947 article for Foreign Affairs—written under the pseudonym “Mr. X”—George Kennan warned that Americans should “continue to regard the Soviet Union as a rival, not a partner,” since Stalin harbored “no real faith in the possibility of a permanent happy coexistence of the Socialist and capitalist worlds.” He urged US leaders to pursue “a policy of firm containment, designed to confront the Russians.”7

Truman, on March 12, 1947, announced $400 million in aid to Greece and Turkey, where “terrorist activities…led by Communists” jeopardized “democratic” governance. With Britain “reducing or liquidating its commitments in several parts of the world, including Greece,” it fell on the US, Truman said, “to support free peoples…resisting attempted subjugation by…outside pressures.”8 The so-called “Truman Doctrine” became a cornerstone of the American policy of containment.9

In the harsh winter of 1946-47, famine loomed in much of continental Europe. Blizzards and freezing cold halted coal production. Factories closed. Unemployment spiked. Amid these conditions, the Communist parties of France and Italy gained nearly a third of the seats in their respective Parliaments. American officials worried that Europe’s impoverished masses were increasingly vulnerable to Soviet propaganda. The situation remained dire through the spring, when Secretary of State General George Marshall gave an address at Harvard University, on June 5, 1947, suggesting that “the United States should do whatever it is able to do to assist in the return of normal economic health to the world, without which there can be no political stability and no assured peace.”10 Although Marshall had stipulated to potential critics that his proposal was “not directed against any country, but against hunger, poverty…and chaos,” Stalin clearly understood the development of the ERP as an assault against Communism in Europe: he saw it as a “Trojan Horse” designed to lure Germany and other countries into the capitalist web.11

The European Recovery Program (ERP), popularly known as the Marshall Plan, pumped enormous sums of capital into Western Europe. From 1948-1952 the US invested $13 billion toward reconstruction while simultaneously loosening trade barriers. To avoid the postwar chaos of World War I, the Marshall Plan was designed to rebuild Western Europe, open markets, and win European support for capitalist democracies. The Soviets countered with their rival Molotov Plan, a symbolic pledge of aid to Eastern Europe. Polish leader Józef Cyrankiewicz was rewarded with a five-year, $450 million dollar trade agreement from Russia for boycotting the Marshall Plan. Stalin was jealous of Eastern Europe. When Czechoslovakia received $200 million of American assistance, Stalin summoned Czech foreign minister Jan Masaryk to Moscow. Masaryk later recounted that he “went to Moscow as the foreign minister of an independent sovereign state,” but “returned as a lackey of the Soviet Government.” Stalin exercised ever tighter control over Soviet “satellite” countries in Central and Eastern Europe.12

The situation in Germany meanwhile deteriorated. Berlin had been divided into communist and capitalist zones. In June 1948, when the US, British, and French officials introduced a new currency, the Soviet Union initiated a ground blockade, cutting off rail and road access to West Berlin (landlocked within the Soviet occupation zone) to gain control over the entire city. The United States organized and coordinated a massive airlift that flew essential supplies into the beleaguered city for eleven months, until the Soviets lifted the blockade on May 12, 1949. Germany was officially broken in half. On May 23, the western half of the country was formally renamed the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) and the eastern Soviet zone became the German Democratic Republic (GDR) later that fall. Berlin, which lay squarely within the GDR, was divided into two sections (and, from August 1961 until November 1989, famously separated by physical walls).13

In the summer of 1949, American officials launched the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), a mutual defense pact in which the US and Canada were joined by England, France, Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Italy, Portugal, Norway, Denmark, and Iceland. The Soviet Union would formalize its own collective defensive agreement in 1955, the Warsaw Pact, which included Albania, Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Poland, and East Germany.

Liberal journalist Walter Lippmann was largely responsible for popularizing the term “the Cold War” in his book, The Cold War: A Study in U.S. Foreign Policy, published in 1947. Lippmann envisioned a prolonged stalemate between the US and the USSR, a war of words and ideas in which direct shots would not necessarily be fired between the two. Lippmann agreed that the Soviet Union would only be “prevented from expanding” if it were “confronted with…American power,” but he felt “that the strategical conception and plan” recommended by Mr. X (George Kennan) was “fundamentally unsound,” as it would require having “the money and the military power always available in sufficient amounts to apply ‘counter-force’ at constantly shifting points all over the world.” Lippmann cautioned against making far-flung, open-ended commitments, favoring instead a more limited engagement that focused on halting the influence of communism in the “heart” of Europe; he believed that if the Soviet system were successfully restrained on the continent, it could otherwise be left alone to collapse under the weight of its own imperfections.14

A new chapter in the Cold War began on October 1, 1949, when the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) led by Mao Tse-tung declared victory against “Kuomintang” Nationalists led by the Western-backed Chiang Kai-shek. The Kuomintang retreated to the island of Taiwan and the CCP took over the mainland under the red flag of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Coming so soon after the Soviet Union’s successful test of an atomic bomb, on August 29, the “loss of China,” the world’s most populous country, contributed to a sense of panic among American foreign policymakers, whose attention began to shift from Europe to Asia. After Dean Acheson became Secretary of State in 1949, Kennan was replaced in the State Department by former investment banker Paul Nitze, whose first task was to help compose, as Acheson later described in his memoir, a document designed to “bludgeon the mass mind of ‘top government’” into approving a “substantial increase” in military expenditures.15

“National Security Memorandum 68: United States Objectives and Programs for National Security,” a national defense memo known as “NSC-68,” achieved its goal. Issued in April 1950, the nearly sixty-page classified memo warned of “increasingly terrifying weapons of mass destruction,” which served to remind “every individual” of “the ever-present possibility of annihilation.” It said that leaders of the USSR and its “international communist movement” sought only “to retain and solidify their absolute power.” As the central “bulwark of opposition to Soviet expansion,” America had become “the principal enemy” that “must be subverted or destroyed by one means or another.” NSC-68 urged a “rapid build-up of political, economic, and military strength” in order to “roll back the Kremlin’s drive for world domination.” Such a massive commitment of resources, amounting to more than a threefold increase in the annual defense budget, was necessary because the USSR, “unlike previous aspirants to hegemony,” was “animated by a new fanatic faith,” seeking “to impose its absolute authority over the rest of the world.”16 Both Kennan and Lippmann were among a minority in the foreign policy establishment who argued to no avail that such a “militarization of containment” was tragically wrongheaded.17

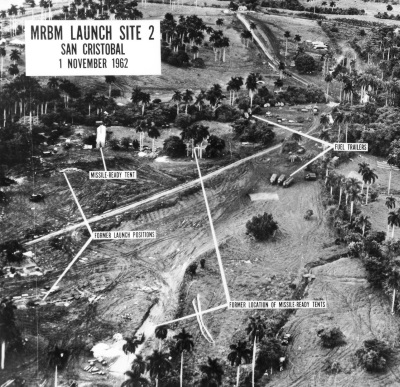

Aerial photograph of a Soviet missile site in Cuba, which provoked the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962.

On June 25, 1950, as US officials were considering the merits of NSC 68’s proposals, including “the intensification of … operations by covert means in the fields of economic … political and psychological warfare” designed to foment “unrest and revolt in … [Soviet] satellite countries,” fighting erupted in Korea between communists in the north and American-backed anti-communists in the south.18

After Japan surrendered in September 1945, a US-Soviet joint occupation had paved the way for the division of Korea. In November 1947, the UN passed a resolution that a united government in Korea should be created but the Soviet Union refused to cooperate. Only the south held elections. The Republic of Korea (ROK), South Korea, was created three months after the election. A month later, communists in the north established the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK). Both claimed to stand for a unified Korean peninsula. The UN recognized the ROK, but incessant armed conflict broke out between North and South.19

In the spring of 1950, Stalin hesitantly endorsed North Korean leader Kim Il Sung’s plan to ‘liberate’ the South by force, a plan heavily influenced by Mao’s recent victory in China. While he did not desire a military confrontation with the US, Stalin thought correctly that he could encourage his Chinese comrades to support North Korea if the war turned against the DPRK. The North Koreans launched a successful surprise attack and Seoul, the capital of South Korea, fell to the communists on June 28. The UN passed resolutions demanding that North Korea cease hostilities and withdraw its armed forces to the 38th parallel and calling on member states to provide the ROK military assistance to repulse the Northern attack.

That July, UN forces mobilized under American General Douglass MacArthur. Troops landed at Inchon, a port city around 30 miles away from Seoul, and took the city on September 28. They moved on North Korea. On October 1, ROK/UN forces crossed the 38th parallel, and on October 26 they reached the Yalu River, the traditional Korea-China border. They were met by 300,000 Chinese troops who broke the advance and rolled up the offensive. On November 30, ROK/UN forces began a fevered retreat. They returned across the 38th parallel and abandoned Seoul on January 4, 1951. The United Nations forces regrouped, but the war entered into a stalemate. General MacArthur, growing impatient and wanting to eliminate the communist threats, requested authorization to use nuclear weapons against North Korea and China. Denied, MacArthur publicly denounced Truman. Truman, unwilling to threaten World War III and refusing to tolerate MacArthur’s public insubordination, dismissed the General in April. On June 23, 1951, the Soviet ambassador to the UN suggested a cease-fire, which the US immediately accepted. Peace talks continued for two years.

General Dwight Eisenhower defeated Illinois Governor Adlai Stevenson in the 1952 presidential election and Stalin died in March 1953. The DPRK warmed to peace, and an armistice agreement was signed on July 27, 1953. Upwards of 1.5 million people had died during the conflict.20

Coming so soon after World War II and ending without clear victory, Korea became for many Americans a “forgotten war.” Decades later, though, the nation’s other major intervention in Asia would be anything but forgotten. The Vietnam War had deep roots in the Cold War world. Vietnam had been colonized by France and seized by Japan during World War II. The nationalist leader Ho Chi Minh had been backed by the US during his anti-Japanese insurgency and, following Japan’s surrender in 1945, “Viet Minh” nationalists, quoting Thomas Jefferson, declared an independent Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV). Yet France moved to reassert authority over its former colony in Indochina, and the United States sacrificed Vietnamese self-determination for France’s colonial imperatives. Ho Chi Minh turned to the Soviet Union for assistance in waging war against the French colonizers in a protracted war.

After French troops were defeated at the ‘Battle of Dien Bien Phu’ in May 1954, US officials helped broker a temporary settlement that partitioned Vietnam in two, with a Soviet/Chinese-backed state in the north and an American-backed state in the south. To stifle communist expansion southward, the United States would send arms, offer military advisors, prop up corrupt politicians, stop elections, and, eventually, send over 500,000 troops, of whom nearly 60,000 would be lost before the communists finally reunified the country.

- Martin McCauley, Origins of the Cold War 1941-49: Revised 3rd Edition (New York: Routledge, 2013), 1401-141. [↩]

- Ibid., 141. [↩]

- For Kennan, see especially John Lewis Gaddis, George F. Kennan: An American Life (New York: Penguin Press, 2011); John Lukacs, editor, George F. Kennan and the Origins of Containment, 1944–1946: The Kennan-Lukacs Correspondence (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1997). [↩]

- Fraser J. Harbutt, Yalta 1945: Europe and America at the Crossroads (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010). [↩]

- Herbert Feis, Between War and Peace: The Potsdam Conference (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1960). [↩]

- (For overviews of the Cold War, see especially John Lewis Gaddis, Strategies of Containment: A Critical Appraisal of Postwar American National Security Policy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1982); John Lewis Gaddis, The Cold War: A New History (New York: Penguin Press, 2005); Melvyn P. Leffler, For the Soul of Mankind: The United States, the Soviet Union, and the Cold War (New York: Hill and Wang, 2007); and Frederick Logevall, America’s Cold War: The Politics of Insecurity (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009). [↩]

- George Kennan, “The Sources of Soviet Conduct,” Foreign Affairs (July 1947), 566-582. [↩]

- Joyce P. Kaufman, A Concise History of U.S. Foreign Policy (Rowman & Littlefield, Jan 16, 2010), 86. [↩]

- Denise. M. Bostdorff, Proclaiming the Truman Doctrine: The Cold War Call to Arms (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1998). [↩]

- Michael Beschloss, Our Documents: 100 Milestone Documents from the National Archives (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), 199. [↩]

- Charles L. Mee, The Marshall Plan: The Launching of the Pax Americana (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1984). [↩]

- Melvyn P. Leffler and Odd Arne Westad, editors, The Cambridge History of the Cold War: Volume 1, Origins (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 189. [↩]

- Daniel F. Harrington, Berlin on the Brink: The Blockade, the Airlift, and the Early Cold War (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 2012). [↩]

- Walter Lippman, The Cold War: A Study in U.S. Foreign Policy (New York: Harper, 1947), 10, 15. [↩]

- James Chace, Acheson: The Secretary Of State Who Created The American World (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2008), 441). [↩]

- Quotes from Curt Cardwell, NSC 68 and the Political Economy of the Early Cold War (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 10-12. [↩]

- Gaddis, Strategies of Containment. [↩]

- Gregory Mitrovich, Undermining the Kremlin: America’s Strategy to Subvert the Soviet Bloc, 1947-1956 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2000), 182. [↩]

- For the Korean War, see especially Bruce Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, 2 vols. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981, 1990); William W. Stueck, The Korean War: An International History (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995). [↩]

Michael Brenes et al (2016). The Cold War. In Ari Cushner (Ed.), The American Yawp. Retrieved from http://www.americanyawp.com/text/25-the-cold-war/

Summary

In many respects, the Cold War represents a departure from more traditional “hot” wars. “Hot” wars are traditional military conflicts between two or more combatants that revolve around armed conflict. The Cold War featured several more traditional “hot” wars, including the Korean War between 1950 and 1953 and the Vietnam War between 1955 and 1975. However, the Cold War also represented an ideological, technological, and even cultural competition between the United States and the Soviet Union and their allies.

By the early 1950s, the major contours of the Cold War had already taken shape. An official American government document in 1950 captured the worldview that helped drive the U.S. policy towards the Cold War for decades. Commenting on U.S. policy during the war with the Soviet Union, the document asserted, “the whole success of the proposed program hangs ultimately on recognition by this Government, the American people, and all free peoples, that the cold war is in fact a war in which the survival of the free world is at stake.” As the document indicates, many American policymakers believed that Communism and Communist expansion represented a direct threat to American national security and the international capitalist system. There was no possible middle ground between the communist Soviet Union and the capitalist United States because their economic systems could not coexist. As both nations began to see their spheres of influence expand and began actively seeking allies after World War II, they both began to view the expansion of the other as a direct threat to their own economic and political future.

Ultimately, the Cold War shattered the postwar peace that had emerged after World War II, and drove significant anxiety around the world about nuclear war, shaped anti-Communist hysteria in the United States that influenced American political culture for at least two decades, spurred technological competition between the United States and the Soviet Union that culminated in America landing on the moon in 1969, and resulted in numerous military conflicts around the world between 1946 and 1991.