3

Try to imagine the state you currently live in without suburbs. Is it even possible? Suburbs have become one of the defining characteristics of the modern American landscape, and suburbanization represents one of the most significant demographic transformations of the 20th century. Like the nation’s transition from a largely rural to a largely urban nation in the 19th century, suburbanization would have political, social and economic consequences for decades.

Although suburbanization first began in the late 19th century and early 20th century, when wealthy Americans began moving from inner cities to the city outskirts to escape overpopulation and poverty, it would not begin in earnest until the middle of the twentieth century when economic and technological conditions finally made it possible for members of the middle class to purchase homes and live further away from city centers. Access to home mortgages, the construction of federal highways, and a postwar economic boom gave millions of Americans the ability to move away from cities, where a significant percentage of Americans were employed before World War II, to the suburbs. Recognizing the potential market in suburban homes, builders like William Levitt raced to build sprawling neighborhoods of single-family homes that quickly dotted the country. Industries and business quickly followed the new suburbanites to the suburbs, and the suburbs experienced explosive growth for nearly two decades.

The Rise of the Suburbs

While the electric streetcar of the late-nineteenth century facilitated the outward movement of the well to do, the seeds of a suburban nation were planted in the mid-twentieth century. At the height of the Great Depression, in 1932, some 250,000 households lost their property to foreclosure. A year later, half of all U.S. mortgages were in default. The foreclosure rate stood at more than a 1,000 per day. In response, FDR’s New Deal created the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC), which began purchasing and refinancing existing mortgages at risk of default. HOLC introduced the amortized mortgage, allowing borrowers to pay back interest and principal regularly over fifteen years instead of the then standard five-year mortgage that carried large balloon payments at the end of the contract. The HOLC eventually owned nearly one of every five mortgages in America. Though homeowners paid more for their homes under this new system, home-ownership was opened to the multitudes who could now gain residential stability, lower monthly mortgage payments, and accrue equity and wealth as property values rose over time.

Additionally, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), another New Deal organization, increased access to home ownership by insuring mortgages and protecting lenders from financial loss in the event of a default. Lenders, however, had to agree to offer low rates and terms of up to twenty or thirty years. Even more consumers could afford homes. Though only slightly more than a third of homes had an FHA-backed mortgage by 1964, FHA loans had a ripple effect, with private lenders granting more and more home loans even to non-FHA-backed borrowers. The effects of government programs and subsidies like HOLC and the FHA were fully felt in the postwar economy and fueled the growth of homeownership and the rise of the suburbs.

Government spending during World War II pushed the United States out of the Depression and into an economic boom that would be sustained after the war by continued government spending. Government expenditures provided loans to veterans, subsidized corporate research and development, and built the interstate highway system. In the decades after World War II, business boomed, unionization peaked, wages rose, and sustained growth buoyed a new consumer economy. The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act (popularly known as the G.I. Bill), passed in 1944, offered low-interest home loans, a stipend to attend college, loans to start a business, and unemployment benefits.

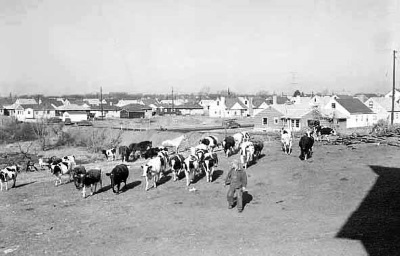

The rapid growth of homeownership and the rise of suburban communities helped drive the postwar economic boom. Builders created sprawling neighborhoods of single-family homes on the outskirts of American cities. William Levitt built the first Levittown, the prototypical suburban community, in 1946 in Long Island, New York. Purchasing large acreage, “subdividing” lots, and contracting crews to build countless homes at economies of scale, Levitt offered affordable suburban housing to veterans and their families. Levitt became the prophet of the new suburbs and his model of large-scale suburban development was duplicated by developers across the country. The country’s suburban share of the population rose from 19.5% in 1940 to 30.7% by 1960. Homeownership rates rose from 44% in 1940 to almost 62% in 1960. Between 1940 and 1950, suburban communities of greater than 10,000 people grew 22.1%, and planned communities grew at an astonishing rate of 126.1%.4 As historian Lizabeth Cohen notes, these new suburbs “mushroomed in territorial size and the populations they harbored.” Between 1950 and 1970, America’s suburban population nearly doubled to 74 million. 83 percent of all population growth occurred in suburban places.

The postwar construction boom fed into countless industries. As manufacturers converted back to consumer goods after the war, and as the suburbs developed, appliance and automobile sales rose dramatically. Flush with rising wages and wartime savings, homeowners also used newly created installment plans to buy new consumer goods at once instead of saving for years to make major purchases. Credit cards, first issued in 1950, further increased access to credit. No longer stymied by the Depression or wartime restrictions, consumers bought countless washers, dryers, refrigerators, freezers, and, suddenly, televisions. The percentage of Americans that owned at least one television increased from 12% in 1950 to more than 87% in 1960. This new suburban economy also led to increased demand for automobiles. The percentage of American families owning cars increased from 54% in 1948 to 74% in 1959. Motor fuel consumption rose from some 22 million gallons in 1945 to around 59 million gallons in 1958.

Seen from a macroeconomic level, the postwar economic boom turned America into a land of abundance. For advantaged buyers, loans had never been easier to obtain, consumer goods had never been more accessible, and well-paying jobs had never been more abundant. “If you had a college diploma, a dark suit, and anything between the ears,” a businessman later recalled, “it was like an escalator; you just stood there and you moved up.” But the “escalator” did not serve everyone. Beneath the aggregate numbers, racial disparity, sexual discrimination, and economic inequality persevered, undermining many of the assumptions of an Affluent Society.

In 1939 real estate appraisers arrived in sunny Pasadena, California. Armed with elaborate questionnaires to evaluate the city’s building conditions, the appraisers were well-versed in the policies of the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC). In one neighborhood, the majority of structures were rated in “fair” repair and it was noted that there was a lack of “construction hazards or flood threats.” However, appraisers concluded that the area “is detrimentally affected by 10 owner occupant Negro families.” While “the Negroes are said to be of the better class,” the appraisers concluded, “it seems inevitable that ownership and property values will drift to lower levels.”

While suburbanization and the new consumer economy produced unprecedented wealth and affluence, the fruits of this economic abundance did not reach all Americans equally. Wealth created by the booming economy filtered through social structures with built-in privileges and prejudices. Just when many middle- and working-class white American families began their journey of upward mobility by moving to the suburbs with the help of government programs such as the FHA and the GI Bill, many African Americans and other racial minorities found themselves systematically shut out.

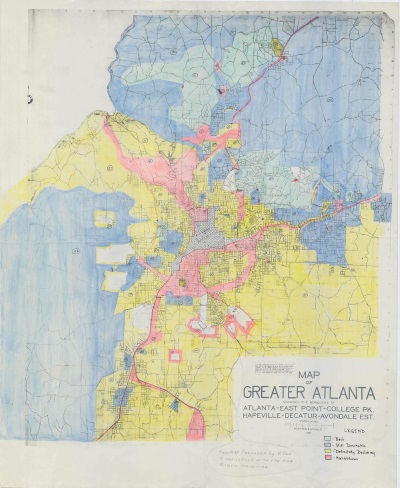

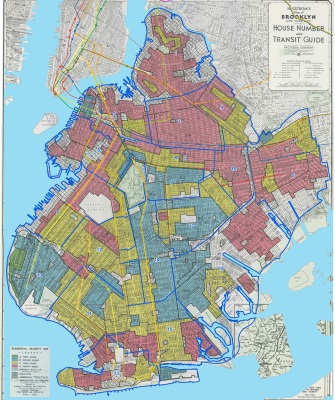

A look at the relationship between federal organizations such as the HOLC and FHA and private banks, lenders, and real estate agents tells the story of standardized policies that produced a segregated housing market. At the core of HOLC appraisal techniques, which reflected the existing practices of private realtors, was the pernicious insistence that mixed-race and minority-dominated neighborhoods were credit risks. In partnership with local lenders and real estate agents, HOLC created Residential Security Maps to identify high and low risk-lending areas. People familiar with the local real estate market filled out uniform surveys on each neighborhood. Relying on this information, HOLC assigned every neighborhood a letter grade from A to D and a corresponding color code. The least secure, highest risk neighborhoods for loans received a D grade and the color red. Banks limited loans in such “redlined” areas.

Phrases like “subversive racial elements” and “racial hazards” pervade the redlined area description files of surveyors and HOLC officials. Los Angeles’ Echo Park neighborhood, for instance, had concentrations of Japanese and African Americans and a “sprinkling of Russians and Mexicans.” The HOLC security map and survey noted that the neighborhood’s “adverse racial influences which are noticeably increasing inevitably presage lower values, rentals and a rapid decrease in residential desirability.”

While the HOLC was a fairly short-lived New Deal agency, the influence of its security maps lived on in the Federal Housing Authority (FHA) and Veteran’s Administration (VA), the latter of which dispensed GI Bill-backed mortgages. Both of these government organizations, which reinforced the standards followed by private lenders, refused to back bank mortgages in “redlined” neighborhoods. On the one hand, FHA- and VA-backed loans were an enormous boon to those who qualified for them. Millions of Americans received mortgages that they otherwise would not have qualified for. But FHA-backed mortgages were not available to all. Racial minorities could not get loans for property improvements in their own neighborhoods—seen as credit risks—and were denied mortgages to purchase property in other areas for fear that their presence would extend the red line into a new community. Levittown, the poster-child of the new suburban America, only allowed whites to purchase homes. Thus, FHA policies and private developers increased home ownership and stability for white Americans while simultaneously creating and enforcing racial segregation.

The exclusionary structures of the postwar economy prompted protest from the African Americans and other minorities who were excluded. Fair housing, equal employment, consumer access, and educational opportunity, for instance, all emerged as priorities of a brewing civil rights movement. In 1948, the U.S. Supreme Court sided with African American plaintiffs and, in Shelley v. Kraemer, declared racially restrictive neighborhood housing covenants–property deed restrictions barring sales to racial minorities–legally unenforceable. Discrimination and segregation continued, however, activists would continue to push for fair housing practices.

During the 1950s and early 1960s many Americans retreated to the suburbs to enjoy the new consumer economy and search for some normalcy and security after the instability of depression and war. But many could not. It was both the limits and opportunities of housing, then, that shaped the contours of postwar American society.

Attribution:

The Affluent Society. (n.d.). In The American Yawp. Retrieved September 9, 2017, from http://www.americanyawp.com/text/26-the-affluent-society/

Summary

For many white, middle-class Americans, the rise of the suburb represented the culmination of the American dream. The stereotypical suburban home, surrounded by a white picket fence and stocked with all the latest innovations in household appliances, was now within reach for millions of consumers. However, suburbanization did not come without its pitfalls. Although suburbs were celebrated in sitcoms like “Father Knows Best” and “Leave it to Beaver,” many social critics argued that the suburbs bred conformity and shallow values. Malvina Reynolds 1963 song “Little Boxes” is representative of these critiques, and was infamous for deriding the “little boxes made of ticky tacky” which “all look just the same.” More significantly, suburbs were predominantly white, middle-class enclaves. Although there were notable exceptions, many suburban communities around the country explicitly prevented minorities from purchasing homes in their neighborhoods, and historians have highlighted how minorities were systematically denied loans and prevented from partaking in the same government sponsored mortgage programs that made home ownership so accessible to middle-class whites, even when they had the same jobs and financial capital as white home-owners. Finally, the growth of the suburbs would have enormous repercussions on American cities and triggered urban decline throughout the second half of the 20th century.