9

In 1873, the author Mark Twain coined the phrase “The Gilded Age” to describe post-Civil War America. Historians have largely defined the Gilded Age as the period between 1870 and 1900, and the era has become infamous for rampant political corruption, debates between rural and urban factions in the country, labor unrest, and staggering income inequality. In The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today, Twain and Charles Dudley Warner satirized the corruption and ineffective nature of American politics during the period, and estimated that up to 150 congressmen were corrupt. Americans at the time would have understood the reference to “gilding,” which marked a damning critique of American society and indicated that a thin veneer of gold masked the true reality of American politics and public life.

Throughout the era, little was accomplished at the federal level, despite the fact that the nation suffered through an economic recession in the 1870s and witnessed tremendous transformations in American technology, urbanization, and public life in the decades after the Civil War. As a result, many Americans felt that the government was largely powerless or too corrupt to protect the interests of ordinary American citizens.

The office of the presidency was also largely ineffectual during the Gilded Age because of the bitterly partisan climate of the late 19th century. The chaos in American politics during the era was evidenced the assassinations of President James Garfield in 1881 and President William McKinley in 1901, which underscored the general climate of violence, anxiety and anger that marked Gilded Age politics. In the late 1860s and early 1870s, Southern political leaders began to reemerge on the national stage as members of the Democratic Party. Republicans asserted that the Democrats had betrayed the nation during the Civil War, and were unworthy of public office. Democrats, on the other hands, frequently made allusions to Republican corruption and cast suspicion on Republican’s motivations for controlling American politics. Distrust and loss of faith in the major political parties led many Americans to turn elsewhere in order to effect political change, and labor unions, women’s organizations, middle-class reformers, and grassroots farmer organizations became major vehicles for political activism.

In 1887, President Grover Cleveland vetoed the Texas Seed Bill, which would have supplied Texas farmers with seed so they could avoid bankruptcy as a result of a significant drought. Cleveland’s decision to deny Texas farmers assistance in the midst of a natural disaster is a perfect example of Gilded Age politics and highlights how many Americans conceptualized the role of government during the era. In his veto of the bill, Cleveland defended his decision, writing, “federal aid in such cases encourages the expectation of paternal care on the part of the Government and weakens the sturdiness of our national character.” Many Americans would have agreed with Cleveland, and believed that the government could and should do little to protect the interests of ordinary American citizens. However, throughout the Gilded Age, sentiment was slowly growing that the nation’s government could do more to champion the rights and economic security of the American people.

The Gilded Age

The challenges Americans faced in the post-Civil War era extended far beyond the issue of Reconstruction and the challenge of an economy without slavery. Political and social repair of the nation was paramount, as was the correlative question of race relations in the wake of slavery. In addition, farmers faced the task of cultivating arid western soils and selling crops in an increasingly global commodities market, while workers in urban industries suffered long hours and hazardous conditions at stagnant wages.

Farmers, who still composed the largest percentage of the U.S. population, faced mounting debts as agricultural prices spiraled downward. These lower prices were due in large part to the cultivation of more acreage using more productive farming tools and machinery, global market competition, as well as price manipulation by commodity traders, exorbitant railroad freight rates, and costly loans upon which farmers depended. For many, their hard work resulted merely in a continuing decline in prices and even greater debt. These farmers, and others who sought leaders to heal the wounds left from the Civil War, organized in different states, and eventually into a national third-party challenge, only to find that, with the end of Reconstruction, federal political power was stuck in a permanent partisan stalemate, and corruption was widespread at both the state and federal levels.

As the Gilded Age unfolded, presidents had very little power, due in large part to highly contested elections in which relative popular majorities were razor-thin. Two presidents won the Electoral College without a popular majority. Further undermining their efficacy was a Congress comprising mostly politicians operating on the principle of political patronage. Eventually, frustrated by the lack of leadership in Washington, some Americans began to develop their own solutions, including the establishment of new political parties and organizations to directly address the problems they faced. Out of the frustration wrought by war and presidential political impotence, as well as an overwhelming pace of industrial change, farmers and workers formed a new grassroots reform movement that, at the end of the century, was eclipsed by an even larger, mostly middle-class, Progressive movement. These reform efforts did bring about change—but not without a fight.

THE GILDED AGE

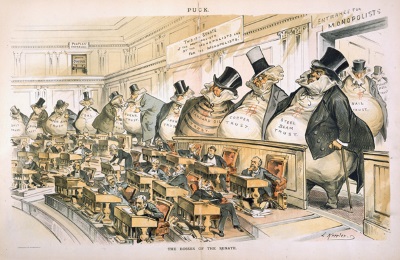

Mark Twain coined the phrase “Gilded Age” in a book he co-authored with Charles Dudley Warner in 1873, The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today. The book satirized the corruption of post-Civil War society and politics. Indeed, popular excitement over national growth and industrialization only thinly glossed over the stark economic inequalities and various degrees of corruption of the era (Figure). Politicians of the time largely catered to business interests in exchange for political support and wealth. Many participated in graft and bribery, often justifying their actions with the excuse that corruption was too widespread for a successful politician to resist. The machine politics of the cities, specifically Tammany Hall in New York, illustrate the kind of corrupt, but effective, local and national politics that dominated the era.

Nationally, between 1872 and 1896, the lack of clear popular mandates made presidents reluctant to venture beyond the interests of their traditional supporters. As a result, for nearly a quarter of a century, presidents had a weak hold on power, and legislators were reluctant to tie their political agendas to such weak leaders. On the contrary, weakened presidents were more susceptible to support various legislators’ and lobbyists’ agendas, as they owed tremendous favors to their political parties, as well as to key financial contributors, who helped them garner just enough votes to squeak into office through the Electoral College. As a result of this relationship, the rare pieces of legislation passed were largely responses to the desires of businessmen and industrialists whose support helped build politicians’ careers.

What was the result of this political malaise? Not surprisingly, almost nothing was accomplished on the federal level. However, problems associated with the tremendous economic growth during this time continued to mount. More Americans were moving to urban centers, which were unable to accommodate the massive numbers of working poor. Tenement houses with inadequate sanitation led to widespread illness. In rural parts of the country, people fared no better. Farmers were unable to cope with the challenges of low prices for their crops and exorbitant costs for everyday goods. All around the country, Americans in need of solutions turned further away from the federal government for help, leading to the rise of fractured and corrupt political groups.

THE ELECTION OF 1876 SETS THE TONE

In many ways, the presidential election of 1876 foreshadowed the politics of the era, in that it resulted in one of the most controversial results in all of presidential history. The country was in the middle of the economic downturn caused by the Panic of 1873, a downturn that would ultimately last until 1879, all but assuring that Republican incumbent Ulysses S. Grant would not be reelected. Instead, the Republican Party nominated a three-time governor from Ohio, Rutherford B. Hayes. Hayes was a popular candidate who advocated for both “hard money”—an economy based upon gold currency transactions—to protect against inflationary pressures and civil servicereform, that is, recruitment based upon merit and qualifications, which was to replace the practice of handing out government jobs as “spoils.” Most importantly, he had no significant political scandals in his past, unlike his predecessor Grant, who suffered through the Crédit Mobilier of America scandal. In this most notorious example of Gilded Age corruption, several congressmen accepted cash and stock bribes in return for appropriating inflated federal funds for the construction of the transcontinental railroad.

The Democrats likewise sought a candidate who could champion reform against growing political corruption. They found their man in Samuel J. Tilden, governor of New York and a self-made millionaire, who had made a successful political career fighting corruption in New York City, including spearheading the prosecution against Tammany Hall Boss William Tweed, who was later jailed. Both parties tapped into the popular mood of the day, each claiming to champion reform and promising an end to the corruption that had become rampant in Washington (Figure). Likewise, both parties promised an end to post-Civil War Reconstruction.

The campaign was a typical one for the era: Democrats shone a spotlight on earlier Republican scandals, such as the Crédit Mobilier affair, and Republicans relied upon the bloody shirt campaign, reminding the nation of the terrible human toll of the war against southern confederates who now reappeared in national politics under the mantle of the Democratic Party. President Grant previously had great success with the “bloody shirt” strategy in the 1868 election, when Republican supporters attacked Democratic candidate Horatio Seymour for his sympathy with New York City draft rioters during the war. In 1876, true to the campaign style of the day, neither Tilden nor Hayes actively campaigned for office, instead relying upon supporters and other groups to promote their causes.

Fearing a significant African American and white Republican voter turnout in the South, particularly in the wake of the Civil Rights Act of 1875, which further empowered African Americans with protection in terms of public accommodations, Democrats relied upon white supremacist terror organizations to intimidate blacks and Republicans, including physically assaulting many while they attempted to vote. The Redshirts, based in Mississippi and the Carolinas, and the White League in Louisiana, relied upon intimidation tactics similar to the Ku Klux Klan but operated in a more open and organized fashion with the sole goal of restoring Democrats to political predominance in the South. In several instances, Redshirts would attack freedmen who attempted to vote, whipping them openly in the streets while simultaneously hosting barbecues to attract Democratic voters to the polls. Women throughout South Carolina began to sew red flannel shirts for the men to wear as a sign of their political views; women themselves began wearing red ribbons in their hair and bows about their waists.

The result of the presidential election, ultimately, was close. Tilden won the popular vote by nearly 300,000 votes; however, he had only 184 electoral votes, with 185 needed to proclaim formal victory. Three states, Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina, were in dispute due to widespread charges of voter fraud and miscounting. Questions regarding the validity of one of the three electors in Oregon cast further doubt on the final vote; however, that state subsequently presented evidence to Congress confirming all three electoral votes for Hayes.

As a result of the disputed election, the House of Representatives established a special electoral commission to determine which candidate won the challenged electoral votes of these three states. In what later became known as the Compromise of 1877, Republican Party leaders offered southern Democrats an enticing deal. The offer was that if the commission found in favor of a Hayes victory, Hayes would order the withdrawal of the remaining U.S. troops from those three southern states, thus allowing the collapse of the radical Reconstruction governments of the immediate post-Civil War era. This move would permit southern Democrats to end federal intervention and control their own states’ fates in the wake of the end of slavery (Figure).

After weeks of deliberation, the electoral commission voted eight to seven along straight party lines, declaring Hayes the victor in each of the three disputed states. As a result, Hayes defeated Tilden in the electoral vote by a count of 185–184 and became the next president. By April of that year, radical Reconstruction ended as promised, with the removal of federal troops from the final two Reconstruction states, South Carolina and Louisiana. Within a year, Redeemers—largely Southern Democrats—had regained control of the political and social fabric of the South.

Although unpopular among the voting electorate, especially among African Americans who referred to it as “The Great Betrayal,” the compromise exposed the willingness of the two major political parties to avoid a “stand-off” via a southern Democrat filibuster, which would have greatly prolonged the final decision regarding the election. Democrats were largely satisfied to end Reconstruction and maintain “home rule” in the South in exchange for control over the White House. Likewise, most realized that Hayes would likely be a one-term president at best and prove to be as ineffectual as his pre-Civil War predecessors.

Perhaps most surprising was the lack of even greater public outrage over such a transparent compromise, indicative of the little that Americans expected of their national government. In an era where voter turnout remained relatively high, the two major political parties remained largely indistinguishable in their agendas as well as their propensity for questionable tactics and backroom deals. Likewise, a growing belief in laissez-faire principles as opposed to reforms and government intervention (which many Americans believed contributed to the outbreak of the Civil War) led even more Americans to accept the nature of an inactive federal government

Section Summary

In the years following the Civil War, American politics were disjointed, corrupt, and, at the federal level, largely ineffective in terms of addressing the challenges that Americans faced. Local and regional politics, and the bosses who ran the political machines, dominated through systematic graft and bribery. Americans around the country recognized that solutions to the mounting problems they faced would not come from Washington, DC, but from their local political leaders. Thus, the cycle of federal ineffectiveness and machine politics continued through the remainder of the century relatively unabated.

Meanwhile, in the Compromise of 1877, an electoral commission declared Rutherford B. Hayes the winner of the contested presidential election in exchange for the withdrawal of federal troops from South Carolina, Louisiana, and Florida. As a result, Southern Democrats were able to reestablish control over their home governments, which would have a tremendous impact on the direction of southern politics and society in the decades to come.

OpenStax CNX. (n.d.). In OpenStax CNX. Retrieved from https://cnx.org/contents/p7ovuIkl@3.38:Cfr6ORw6@3/Political-Corruption-in-Postbe

Summary

After thirty years of largely ineffectual progress on a variety of fronts, the Democratic and Republican parties were both forced into action in the late 1890s in order to ensure their political survival. The Populist Party, labor unions, and middle class reformers threatened to make the Democratic and Republican parties obsolete, and both the Democratic and Republican parties began mirroring some of the platforms of their most vocal critics, which effectively eroded support for their detractors and helped them survive the 19th century. After decades of limited action on the major transformations that plagued post-Civil War America, the nation finally sprang into action near the turn of the 20th century and new legislation began producing reforms that addressed some of the most visible affronts to equality and worker’s rights. The era of monopolies, Robber Barons, and political corruption officially came to a close around 1900, but American politics in the first decade of the 20th century would spend a significant amount of time and energy attempting to address 19th century problems that remained unresolved.

For many Americans, the Gilded Age highlighted the necessity of grassroots political activism in order to actually get the attention of Washington and effect political change. And for their part, many political institutions and politicians realized that being responsive, or at least appearing responsive, to the American voting public was necessary for political survival in the 20th century.