26

The term gilded refers to the process of applying a thin layer of precious metal to the exterior of an object made of a cheaper material. This gilding makes the object appear more glamorous than the underlying reality. Mark Twain coined the phrase “Gilded Age” in a book he co-authored with Charles Dudley Warner in 1873, The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today. The book satirized the corruption of post-Civil War society and politics. Popular excitement over national growth and industrialization only thinly glossed over the stark economic inequalities and various degrees of corruption of the era. The last few decades of the nineteenth century were defined by stark economic inequality and a federal government that continued to cater to the interests of business.

In many ways, the presidential election of 1876 foreshadowed the politics of the era. The Republican nominee, Rutherford B. Hayes, and Democratic nominee, Samuel J. Tilden, both promised to institute reform against growing political corruption. Tilden won the popular vote by nearly 300,000 votes; however, he had only 184 electoral votes, with 185 needed to proclaim formal victory. Three southern states were in dispute due to widespread charges of voter fraud and miscounting.

In a deal known as the Compromise of 1877, Democrats and Republicans resolved this disputed election. In exchange for the presidency, Republicans would order the withdrawal of the remaining U.S. troops from the South, thus allowing the collapse of the radical Reconstruction governments and an end to federal intervention in the South.

Although this deal was unpopular among voters, there was a lack of public outrage over such a transparent compromise, This indicates how little Americans expected of their national government. Combined with a growing belief in laissez-faire principles as opposed to reforms and government intervention (which many Americans believed contributed to the outbreak of the Civil War) more Americans accepted the nature of an inactive federal government.

While the nation’s political leaders proved to be weak and corruptible during this period, the United States experienced a second industrial revolution. This revolution in American industry was the result of technological innovations and national investments that cut the costs of production and distribution allowing for the growth of new national markets.

But, the great wealth of the Gilded Age was concentrated among the few. The increasingly stark contrast between rich and poor combined with horrendous labor conditions gave rise to questions about the government’s role in the economy. From political corruption to government intervention, the Gilded Age set the stage for a shift in the ways in which Americans envisioned the role of government in the economy.

The Guilded Age

The Rise of Scientific Management

By 1900, corporate leaders and wealthy industrialists embraced scientific management to achieve efficiency. The harnessing of electricity, the innovations of machine tools, and mass markets opened by railroad expansion allowed for efficiency through subdividing tasks. Henry Ford made the assembly line famous, allowing the production of automobiles to skyrocket as cost plummeted.

Retailers and advertisers sustained the massive markets needed for mass production and corporate bureaucracies allowed for the management of giant firms. A new class of managers became the middlemen between workers and owners and ensured efficient operation and administration of mass production and mass distribution. Average workers became as interchangeable as the parts they were using.

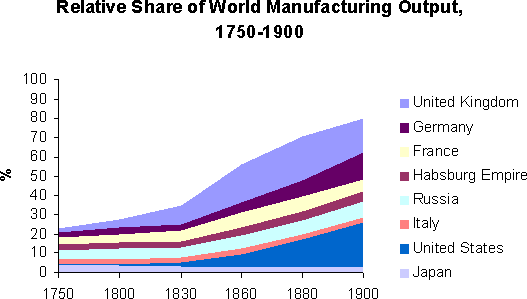

Industrialization and mass production pushed the United States into the forefront of the world. By 1900 the United States was the world’s leading manufacturing nation.

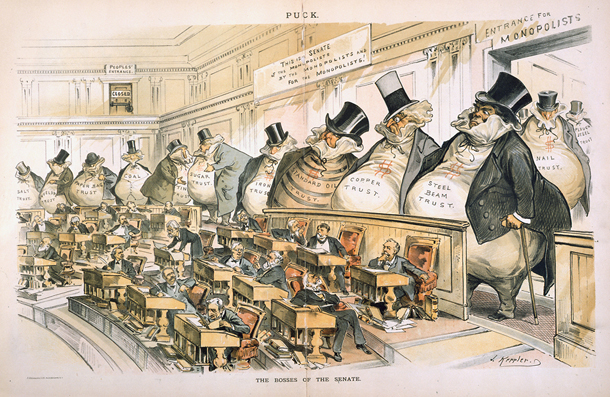

Once the efficiency gains of mass production were realized, however, profit margins could be undone by cutthroat competition. American industrial firms tried everything to avoid competition: they formed informal pools and trusts, entered price-fixing agreements, divided markets, and, when blocked by anti-trust laws and renegade price-cutting, merged.

Between 1895 and 1904, a wave of mergers rocked the American economy. In 9 years, during what is known as “the great merger movement,”4000 companies–nearly 20% of the American economy–were folded into rival firms. 41 separate consolidations controlled over 70% of the market in their respective industries. In 1901, financier J.P. Morgan oversaw the formation of United States Steel. Built from eight leading steel companies, it was the world’s first billion-dollar company and it controlled the market. Monopoly had arrived.

Industrial capitalism created unheard-of fortunes. But it also created millions of low-paid, unskilled, unreliable jobs with long hours and dangerous working conditions. Industrial capitalism created unprecedented inequalities. The sudden appearance of the extreme wealth of industrial and financial leaders alongside the crippling squalor of the urban and rural poor shocked Americans.

The great financial and industrial titans, the so-called “robber barons,” included men like Cornelius Vanderbilt, J.D. Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, and J.P. Morgan. They won fortunes that, adjusted for inflation are still among the largest the nation has ever seen. In 1890, the wealthiest 1% of Americans owned 1/4 of the nation’s assets; the top 10% owned over 70%. By 1900, the richest 10% controlled perhaps 90% of the nation’s wealth.

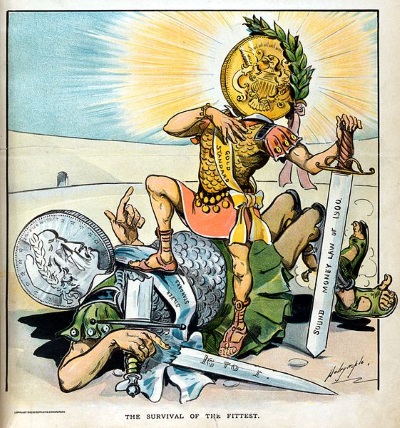

As these unprecedented new fortunes grew among the few, new ideas emerged about their moral legitimacy. Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, On the Origin of Species, appeared in 1859. By the 1870s, his theories had gained widespread traction among the majority of scientists in the United States. One British sociologist and biologist Herbert Spencer, applied Darwin’s theories to society and popularized the phrase “survival of the fittest.” The fittest, Spencer said, would demonstrate their superiority through economic success, while state welfare and private charity would lead to social degeneration and the survival of the weak.

American Laborers Rise UP

American workers toiled in difficult jobs for long hours and little pay. Mechanization and mass production threw skilled laborers into unskilled positions. The typical industrial laborer, which now included women and children, could expect:

- to be unemployed one month/year

- work 60 hours/week

- make an income below the poverty line.

Crowded cities, meanwhile, failed to accommodate growing urban populations and skyrocketing rents trapped families in crowded slums.

The result was industrial strikes. Workers seeking higher wages, shorter hours, and safer working conditions had struck throughout the pre-Civil War era, but organized unions were fleeting and transitory. The Civil War and Reconstruction distracted the nation from the plight of labor, but the growth of big business, unprecedented fortunes, and a vast industrial workforce in the last quarter of the 19th century sparked the rise of an American labor movement.

Union memberships began to climb. The Knights of Labor enjoyed considerable success in the early 1880s, due in part to its efforts to unite skilled and unskilled workers. It welcomed all laborers, including women (the Knights only barred lawyers, bankers, and liquor dealers). By 1886, the Knights had over 700,000 members and envisioned a cooperative producer-centered society that rewarded labor. But, despite their sweeping vision, the Knights focused on practical gains that could be won through the organization of local unions.

In 1886 the Knights organized a campaign for an eight-hour day, culminating in a national strike on May 1, 1886. Between 300,000 and 500,000 workers struck across the country.

In Chicago, police forces had killed several workers while breaking up protestors at the McCormick reaper works. Labor leaders and radicals called for a protest at Haymarket Square on May 4. As police were breaking it up, a bomb exploded killing seven policemen.

Police fired into the crowd, killing four. The deaths of policemen sparked outrage across the nation. The sensationalization of the “Haymarket Riot” led many to associate unionism with radicalism. Eight Chicago anarchists were arrested and, despite no direct evidence linking them to the bombing, found guilty of conspiracy. Four were hanged (one committed suicide before he could be). Membership in the Knights fell rapidly after Haymarket: the group became associated with violence and radicalism. The national movement for an eight-hour day collapsed.

The American Federation of Labor (AFL) emerged as a conservative alternative to the Knights of Labor. An alliance of craft unions (unions composed of skilled workers), the AFL advocated “pure and simple trade unionism,” a program that aimed for: higher wages, fewer hours, and safer conditions through an approach that tried to avoid strikes.

But workers continued to strike. The final two decades of the 19th century saw over 20,000 strikes and lockouts in the United States. Industrial laborers struggled to carve for themselves a piece of the prosperity.

The Founding of the Populist Party

American farmers were also struggling to stay afloat and also lashed out against the inequalities of the Gilded Age. “Wall street owns the country,” one Populist leader told farmers around 1890. “It is no longer a government of the people, by the people, and for the people, but a government of Wall Street, by Wall Street, and for Wall Street.”

Farmers, were still the majority in America in the first decade of the 20th century and were hit especially hard by industrialization. The expanding markets and technological improvements that increased efficiency also decreased commodity prices. Commercialization of agriculture forced small farmers into debt; they lost their land, and were forced into the industrial workforce or, especially in the South, became landless farmworkers.

Frustrated American farmers attempted to reshape the structures of the nation’s political and economic systems, systems they believed enriched bankers and industrial monopolists at the expense of farmers. Farmers organized and launched a challenge to the established political structure first through the cooperatives of the Farmers’ Alliance and later through the politics of the People’s (or Populist) Party.

It began with Texas farmers in Lampasas in 1877, who organized the first Farmers’ Alliance to restore some economic power to farmers by unifying to deal with railroads, merchants, and bankers. They could share machinery, bargain with wholesalers, and negotiate higher prices for their crops. They soon spread from town to town across the South, Midwest, and the Great Plains, holding evangelical-style camp meetings, distributing pamphlets, and establishing over 1,000 Alliance newspapers. As the Alliance spread, so too did its near-religious vision of the nation’s future as a “cooperative commonwealth” that would protect the interests of the many from the predatory greed of the few. At its peak, the Farmers’ Alliance claimed 1,500,000 members meeting in 40,000 local sub-alliances.

In the South, Alliance-backed Democratic candidates won 4 governorships and 48 congressional seats in 1890. But at a time when falling prices and rising debts conspired against the survival of family farmers, the Republicans and Democrats seemed incapable of representing the needs of poor farmers. And so Alliance members organized a political party—the People’s Party, or the Populists, as they came to be known. The Populists attracted supporters across the nation by appealing to:

- those convinced of flaws in the political economy

- veterans of earlier fights for currency reform

- disaffected industrial laborers

- proponents of socialism

- champions of a farmer-friendly “single-tax”

The Populists nominated former Civil War general James B. Weaver as their presidential candidate at the party’s first national convention in Omaha, Nebraska, on July 4, 1892.

The party adopted a platform that crystallized the Alliance’s cooperative program into a coherent political vision. The Omaha Platform and the larger Populist movement sought an unprecedented expansion of federal power. Among other things, it advocated nationalizing the country’s railroad and telegraph systems to ensure that essential services would be run in the best interests of the people. To save debtors, it promoted an inflationary monetary policy by monetizing silver. The combination of efforts would, Populists believed, shift economic and political power back toward the nation’s producing classes.

In the Populists’ first national campaign in 1892, Weaver received over one million votes (and 22 electoral votes), a truly startling performance that signaled a bright future for the Populists. When the Panic of 1893 sparked a severe economic depression, the Populist movement won further credibility. In the 1894 elections, Populists elected 6 senators and 7 representatives to Congress.

The Populist Party seemed poised to capture political victory. And yet, even as Populism gained national traction, the movement was stumbling. The party’s often divided leadership found it difficult to create unified political action with a diverse and loosely organized coalition; state party leaders selectively embraced portions of the Omaha platform; in the South, white supremacy hindered a grand union of black and white workers; and more importantly, the institutionalized parties were still too strong.

A short explanation of the Knights of Labor

ColumbiaLearn (May 11, 2015). MOOC|The Labor Question|The Civil War and Reconstruction, 1865-1890|3.8.5. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3gTU_qS_ikQ

A description of Populism using the Wizard of OZ

Jonathan Rodvelt. (March 20, 2013). The Wizard of Oz [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bl7lqyoi5Rg

Wright, Ben and Joseph Locke, Eds.(2017). The American Yawp. Retrieved from http://www.americanyawp.com/index.html With adjustments by Margaret Carmack.

The “Omaha Platform” of the People’s Party (1892)

In 1892, the People’s, or Populist, Party crafted a platform that indicted the corruptions of the Gilded Age and promised government policies to aid “the people.”

PREAMBLE

The conditions which surround us best justify our co-operation; we meet in the midst of a nation brought to the verge of moral, political, and material ruin. Corruption dominates the ballot-box, the Legislatures, the Congress, and touches even the ermine of the bench. The people are demoralized; most of the States have been compelled to isolate the voters at the polling places to prevent universal intimidation and bribery. The newspapers are largely subsidized or muzzled, public opinion silenced, business prostrated, homes covered with mortgages, labor impoverished, and the land concentrating in the hands of capitalists. The urban workmen are denied the right to organize for self-protection, imported pauperized labor beats down their wages, a hireling standing army, unrecognized by our laws, is established to shoot them down, and they are rapidly degenerating into European conditions. The fruits of the toil of millions are boldly stolen to build up colossal fortunes for a few, unprecedented in the history of mankind; and the possessors of those, in turn, despise the republic and endanger liberty. From the same prolific womb of governmental injustice we breed the two great classes—tramps and millionaires.

The national power to create money is appropriated to enrich bondholders; a vast public debt payable in legal tender currency has been funded into gold-bearing bonds, thereby adding millions to the burdens of the people.

Silver, which has been accepted as coin since the dawn of history, has been demonetized to add to the purchasing power of gold by decreasing the value of all forms of property as well as human labor, and the supply of currency is purposely abridged to fatten usurers, bankrupt enterprise, and enslave industry. A vast conspiracy against mankind has been organized on two continents, and it is rapidly taking possession of the world. If not met and overthrown at once it forebodes terrible social convulsions, the destruction of civilization, or the establishment of an absolute despotism.

We have witnessed for more than a quarter of a century the struggles of the two great political parties for power and plunder, while grievous wrongs have been inflicted upon the suffering people. We charge that the controlling influences dominating both these parties have permitted the existing dreadful conditions to develop without serious effort to prevent or restrain them. Neither do they now promise us any substantial reform. They have agreed together to ignore, in the coming campaign, every issue but one. They propose to drown the outcries of a plundered people with the uproar of a sham battle over the tariff, so that capitalists, corporations, national banks, rings, trusts, watered stock, the demonetization of silver and the oppressions of the usurers may all be lost sight of. They propose to sacrifice our homes, lives, and children on the altar of mammon; to destroy the multitude in order to secure corruption funds from the millionaires.

Assembled on the anniversary of the birthday of the nation, and filled with the spirit of the grand general and chief who established our independence, we seek to restore the government of the Republic to the hands of “the plain people,” with which class it originated. We assert our purposes to be identical with the purposes of the National Constitution; to form a more perfect union and establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty for ourselves and our posterity.

We declare that this Republic can only endure as a free government while built upon the love of the whole people for each other and for the nation; that it cannot be pinned together by bayonets; that the civil war is over, and that every passion and resentment which grew out of it must die with it, and that we must be in fact, as we are in name, one united brotherhood of free men.

Our country finds itself confronted by conditions for which there is no precedent in the history of the world; our annual agricultural productions amount to billions of dollars in value, which must, within a few weeks or months, be exchanged for billions of dollars’ worth of commodities consumed in their production; the existing currency supply is wholly inadequate to make this exchange; the results are falling prices, the formation of combines and rings, the impoverishment of the producing class. We pledge ourselves that if given power we will labor to correct these evils by wise and reasonable legislation, in accordance with the terms of our platform.

We believe that the power of government—in other words, of the people—should be expanded (as in the case of the postal service) as rapidly and as far as the good sense of an intelligent people and the teachings of experience shall justify, to the end that oppression, injustice, and poverty shall eventually cease in the land.

While our sympathies as a party of reform are naturally upon the side of every proposition which will tend to make men intelligent, virtuous, and temperate, we nevertheless regard these questions, important as they are, as secondary to the great issues now pressing for solution, and upon which not only our individual prosperity but the very existence of free institutions depend; and we ask all men to first help us to determine whether we are to have a republic to administer before we differ as to the conditions upon which it is to be administered, believing that the forces of reform this day organized will never cease to move forward until every wrong is remedied and equal rights and equal privileges securely established for all the men and women of this country.

PLATFORM

We declare, therefore—

First.—That the union of the labor forces of the United States this day consummated shall be permanent and perpetual; may its spirit enter into all hearts for the salvation of the Republic and the uplifting of mankind.

Second.—Wealth belongs to him who creates it, and every dollar taken from industry without an equivalent is robbery. “If any will not work, neither shall he eat.” The interests of rural and civic labor are the same; their enemies are identical.

Third.—We believe that the time has come when the railroad corporations will either own the people or the people must own the railroads, and should the government enter upon the work of owning and managing all railroads, we should favor an amendment to the Constitution by which all persons engaged in the government service shall be placed under a civil-service regulation of the most rigid character, so as to prevent the increase of the power of the national administration by the use of such additional government employes.

FINANCE.—We demand a national currency, safe, sound, and flexible, issued by the general government only, a full legal tender for all debts, public and private, and that without the use of banking corporations, a just, equitable, and efficient means of distribution direct to the people, at a tax not to exceed 2 per cent. per annum, to be provided as set forth in the sub-treasury plan of the Farmers’ Alliance, or a better system; also by payments in discharge of its obligations for public improvements.

- We demand free and unlimited coinage of silver and gold at the present legal ratio of l6 to 1.

- We demand that the amount of circulating medium be speedily increased to not less than $50 per capita.

- We demand a graduated income tax.

- We believe that the money of the country should be kept as much as possible in the hands of the people, and hence we demand that all State and national revenues shall be limited to the necessary expenses of the government, economically and honestly administered.

- We demand that postal savings banks be established by the government for the safe deposit of the earnings of the people and to facilitate exchange.

TRANSPORTATION—Transportation being a means of exchange and a public necessity, the government should own and operate the railroads in the interest of the people. The telegraph, telephone, like the post-office system, being a necessity for the transmission of news, should be owned and operated by the government in the interest of the people.

LAND.—The land, including all the natural sources of wealth, is the heritage of the people, and should not be monopolized for speculative purposes, and alien ownership of land should be prohibited. All land now held by railroads and other corporations in excess of their actual needs, and all lands now owned by aliens should be reclaimed by the government and held for actual settlers only.

EXPRESSION OF SENTIMENTS

Your Committee on Platform and Resolutions beg leave unanimously to report the following:

Whereas, Other questions have been presented for our consideration, we hereby submit the following, not as a part of the Platform of the People’s Party, but as resolutions expressive of the sentiment of this Convention.

- RESOLVED, That we demand a free ballot and a fair count in all elections and pledge ourselves to secure it to every legal voter without Federal Intervention, through the adoption by the States of the unperverted Australian or secret ballot system.

- RESOLVED, That the revenue derived from a graduated income tax should be applied to the reduction of the burden of taxation now levied upon the domestic industries of this country.

- RESOLVED, That we pledge our support to fair and liberal pensions to ex-Union soldiers and sailors.

- RESOLVED, That we condemn the fallacy of protecting American labor under the present system, which opens our ports to the pauper and criminal classes of the world and crowds out our wage-earners; and we denounce the present ineffective laws against contract labor, and demand the further restriction of undesirable emigration.

- RESOLVED, That we cordially sympathize with the efforts of organized workingmen to shorten the hours of labor, and demand a rigid enforcement of the existing eight-hour law on Government work, and ask that a penalty clause be added to the said law.

- RESOLVED, That we regard the maintenance of a large standing army of mercenaries, known as the Pinkerton system, as a menace to our liberties, and we demand its abolition. . . .

- RESOLVED, That we commend to the favorable consideration of the people and the reform press the legislative system known as the initiative and referendum.

- RESOLVED, That we favor a constitutional provision limiting the office of President and Vice-President to one term, and providing for the election of Senators of the United States by a direct vote of the people.

- RESOLVED, That we oppose any subsidy or national aid to any private corporation for any purpose.

- RESOLVED, That this convention sympathizes with the Knights of Labor and their righteous contest with the tyrannical combine of clothing manufacturers of Rochester, and declare it to be a duty of all who hate tyranny and oppression to refuse to purchase the goods made by the said manufacturers, or to patronize any merchants who sell such goods.

Source: Edward McPherson, A Handbook of Politics for 1892 (Washington D.C.: James J. Chapman, 1892), 269-271.

The American Yawp Reader. Located at: http://www.americanyawp.com/reader.html. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

Summary

The march of capital transformed patterns of American life. Industrial capitalism brought wealth and it brought poverty. Some Americans enjoyed unprecedented levels of wealth, and an ever-growing slice of middle-class workers gained an increasingly more comfortable standard of living as they entered the industrial workforce as managers. But vast numbers of farmers lost their land and a growing industrial working class struggled to earn wages sufficient to support themselves and their families.

Faced with growing inequality, industrial workers and small farmers began to form alliances to combat the power of big business and capital. The Gilded Age saw a rise in the number of union members as well as union activity. And although at first glance the Populist movement appears to have been a failure—its minor electoral gains were short-lived, it did little to dislodge the entrenched two-party system, and the Populist dream of a cooperative commonwealth never took shape—yet, in terms of lasting impact, the Populist Party proved the most significant third-party movement in American history. The agrarian revolt would establish the roots of later reform and the majority of policies outlined within the Omaha Platform would eventually be put into law over the following decades under the management of middle-class reformers. In large measure, the Populist vision laid the intellectual groundwork for the coming progressive movement and challenged Americans’ previously held fundamental beliefs about the government’s role in the economy.

But as seen in reactions to strikes and the fate of the Populist Party, the federal government continued to side with the interests of big business. Capital was driving the new American economy with the support of Washington. And although the stark contrast between the rich and the poor that had come with the economic boom and industrial expansion of the Gilded Age gave way to the Progressive Era and the push for reform to laws governing business and workers rights, there remained little regulation of businesses practices.