27

The “roaring” 1920s, was a decade of great prosperity, filled with the expansion of consumerism, business, and investing. As President Calvin Coolidge notably said, “The chief business of the American people is business.” Coolidge worked to support business interests and wealthy Americans by lowering taxes and maintaining high tariffs. The 1920s was a decade that can be defined by the rise in consumption and leisure spending.

But the nation’s economy was also creeping towards disaster. Flailing European economies, high tariffs, wealth inequality, a construction bubble, and an ever-more flooded consumer market loomed in the backdrop. In a moment, the nation’s glitz and glamour seemed to give way to decay and despair. For farmers, racial minorities, unionized workers, and other populations that did not share in 1920s prosperity, the veneer of a Jazz Age and a booming economy had always been a fiction. But by 1930, the majority of Americans all shared in the struggle to find economic security in the wake of a financial crisis that began with a crash in the Stock Market on October 29, 1929.

The Great Depression dominated much of the decade that followed. The government’s initial response under Republican Herbert Hoover proved greatly inadequate. This was exacerbated by an environmental disaster that turned much of the middle of the country into a “Dust Bowl.” All of these reshaped American society. The experience of living through this Depression would fundamentally alter the relationship between the American people and the federal government.

The Great Depression

Origins of the Crash

Herbert Hoover was a self-made millionaire who had been the popular head of the wartime Food Administration and served as Secretary of Commerce during the 1920s. In this position he oversaw the decade’s sustained economic growth, and took much of the credit. During his presidential campaign, Hoover claimed that America had never been closer to eliminating poverty and that the Republican Party had brought prosperity.

He ignored the economic troubles such as large rates of poverty and unparalleled levels of inequality. Continued industrial expansion flooded the market with consumer products such as ready-to-wear clothing, convenience foods, and home appliances. Output had risen so dramatically that many feared supply would outpace demand. American businessmen attempted to avoid this catastrophe by developing new merchandising and marketing strategies such as mail-order catalogs, and national branding, that transformed distribution and stimulated a new culture of consumer desire.

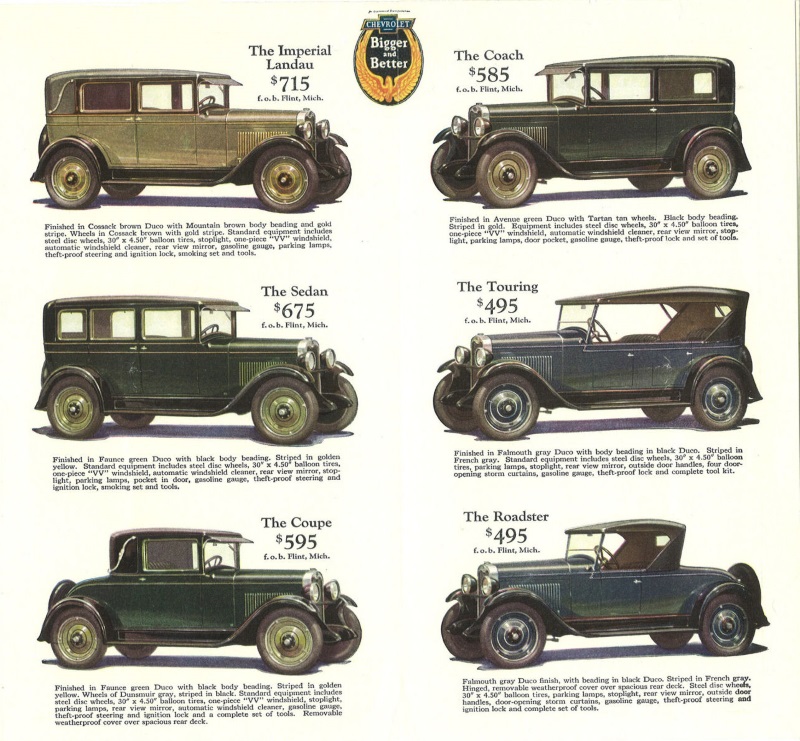

The automobile industry also fostered the new culture of consumption by promoting the use of credit. By 1927, more than 60% of American automobiles were sold on credit, and installment purchasing was made available for nearly every other large consumer purchase. Spurred by access to easy credit, consumer expenditures for household appliances, for example, grew by more than 120% between 1919 and 1929. Henry Ford’s assembly line brought automobiles within the reach of middle-income Americans. By 1925, Ford’s factories were turning out a Model-T every 10 seconds.

However, an economy built on credit was risky. With the federal government continuing to support a laissez-faire or a hands off approach to business regulation, businesses were free to speculate. The Stock Market became the wonder of the decade and banks invested heavily.

On Thursday, October 24, 1929, stock market prices suddenly plummeted. Ten billion dollars in investments (roughly equivalent to about $100 billion today) disappeared in a matter of hours. Fears spread and the following week more frightened investors dumped their portfolios to avoid further losses. On October 29, “Black Tuesday,” the stock market began its long precipitous fall. Stock values evaporated. Four-fifths of J.D. Rockefeller’s fortune—the greatest in American history—vanished.

Although the Crash stunned the nation, it exposed the underlying problems with the American economy in the 1920s. The stock market’s popularity had grown throughout the decade, but only 2.5% of Americans had brokerage accounts; the overwhelming majority of Americans had no stake in Wall Street. The stock market’s collapse, no matter how dramatic, did not by itself depress the American economy. Instead, the Crash exposed a great number of factors which, when combined with the financial panic, sunk the American economy into an economic crisis. Rising inequality, declining demand, rural collapse, overextended investors, and the bursting of speculative bubbles all conspired to plunge the nation into the Great Depression.

The pro-business policies of the 1920s were designed for an American economy built upon the production and consumption of durable goods. Federal fiscal policies exacerbated the economic divide: low corporate and personal taxes, easy credit, and depressed interest rates favored wealthy investors who spent their money on luxury goods and speculative investments. Yet, by the late 1920s, much of the market was saturated. More and more, people had no need for the new automobiles, radios, and other consumer goods that fueled GDP growth in the 1920s. When products failed to sell, inventories piled up and companies fired workers, stripping potential consumers of cash, blunting demand for consumer goods, and replicating the downward economic cycle. Despite impressive overall growth throughout the 1920s, unemployment hovered around 7% throughout the decade.

For American farmers, meanwhile, “hard times” began long before the markets crashed. In 1920 and 1921, after several years of larger-than-average profits, farm prices declined, plummeting as production climbed and domestic and international demand for cotton, foodstuffs, and other agricultural products stalled. Widespread soil exhaustion on western farms compounded the problem. Farmers found themselves unable to make payments on loans taken out during the good years, and banks in agricultural areas tightened credit in response. By 1929, many farm families were at a breaking point.

Despite serious foundational problems in the industrial and agricultural economy, most Americans in 1929 and 1930 still believed the economy would bounce back. During his 1928 campaign, Hoover promoted higher tariffs to encourage consumption and protect farmers from foreign competition. Spurred by the ongoing agricultural depression, Hoover signed the highest tariff in American history, the Smoot-Hawley Tariff of 1930. Other countries responded in kind, tariffs rose across the globe, and international trade halted. Between 1929 and 1932, international trade dropped from $36 billion to only $12 billion. American exports fell by 78%.

The final contributing element of the Great Depression was a human one: panic. The frantic reaction to the market’s fall exacerbated the economy’s other failings.

Economic policies backfired;

- the Federal Reserve over-corrected by raising interest rates and tightening credit

- banks denied loans and called in debts

- bank patrons, afraid that this meant further financial trouble, rushed to withdraw money before institutions could close.

By 1930, with the economy worsening and panic accelerating, 1,352 banks failed. In 1932, nearly 2,300 banks collapsed, taking personal deposits, savings, and credit with them.

Herbert Hoover & Federal Response

As the Depression worked its way across the country, public blame soon settled on the President and the Republican Party’s conservative politics. Hoover shared the common belief that direct government aid discouraged a healthy work ethic. He embraced a system of voluntary action called “Associationalism” that assumed:

- Americans could maintain a web of voluntary cooperative organizations dedicated to providing economic assistance and services to those in need

- Businesses would willingly limit harmful practices for the greater economic good

This would encourage:

- Self Control

- Self-initiative

But when the Depression exposed the incapacity of such strategies to produce an economic recovery, the ideology failed, and so too did his presidency.

Like all too many Americans, Hoover and his advisers assumed that the sharp financial and economic decline was a temporary downturn, another “bust” of the inevitable boom-bust cycles that stretched back through America’s commercial history. Many economists argued that periodic busts culled weak firms and paved the way for future growth.

When suffering Americans looked to Hoover for help, his only answer was volunteerism. He asked business leaders to promise to maintain investments and employment and encouraged state and local charities to provide assistance to those in need. Hoover established the President’s Organization for Unemployment Relief, or POUR, to help organize the efforts of private agencies. But charitable relief organizations were overwhelmed by the growing number of unemployed, underfed, and unhoused Americans. By mid-1932, for instance, a quarter of all of New York’s private charities closed due to lack of money.

In 1932, with a reelection campaign looming, Hoover created the Reconstruction Finance Corporation to provide emergency loans to banks, building-and-loan societies, railroads, and other private industries to stimulate industry. It was radical in its use of direct government aid, but it also bypassed needy Americans to bolster industrial and financial interests. New York Congressman Fiorello LaGuardia, captured public sentiment when he denounced the RFC as a “millionaire’s dole.”

Summer 1932: The Bonus Army

As the depression deepened, Americans increasingly looked to the federal government to take more concrete action to help average Americans. Congress debated a bill authorizing immediate payment of long-promised cash bonuses to veterans of World War I, originally scheduled to be paid out in 1945. The bonus came to symbolize government relief for the most deserving recipients, and from across the country more than 15,000 unemployed veterans and their families converged on Washington, D.C. They erected a tent city across the Potomac River.

Concerned with what immediate payment would do to the federal budget, Hoover opposed the bill, which was voted down by the Senate. While most of the “Bonus Army” left Washington in defeat, many stayed to press their case. Hoover called the remaining veterans “insurrectionists” and ordered them to leave. When thousands failed to vacate, General Douglas MacArthur, accompanied by local police, infantry, cavalry, tanks, and a machine gun squadron, stormed the tent city. National media covered the event as troops chased down men and women, tear-gassed children, and torched the shantytown.

Hoover of course was not responsible for the Depression, not personally. But his insensitivity toward suffering Americans, his unwillingness to address widespread economic problems, and his repeated platitudes about returning prosperity condemned his presidency.

Living Through the Great Depression

As the United States slid ever deeper into the Great Depression, Americans faced the painful, frightening, and often bewildering collapse of the economic institutions upon which they depended. With rampant unemployment and declining wages, Americans slashed expenses. The fortunate survived by deferring vacations and regular consumer purchases. Middle- and working-class Americans might rely upon disappearing credit at neighborhood stores, default on utility bills, or skip meals. Those that could borrowed from relatives or took in boarders in homes or “doubled up” in tenements. The most desperate, the chronically unemployed, encamped on public or marginal lands in “Hoovervilles” that dotted America’s cities, depending upon breadlines and peddling. Poor women and children entered the labor force, as they always had. The ideal of the “male breadwinner” was always a fiction for poor Americans, but the Depression decimated millions of new workers. The emotional and psychological shocks of unemployment only added to the material deprivations of the Depression.

Wright, Ben and Joseph Locke, Eds.(2017). The American Yawp. Retrieved from http://www.americanyawp.com/index.html

With adjustments by Margaret Carmack.

March of the Bonus Army

Interviews from those who experienced the Bonus Army. And commentary from historians. Gives students an idea how the government responded to the beginnings of the Great Depression.

The entire story is worthwhile, but you will specifically want to listen to the first 3:15min and then pick up again at 5 minutes through the end.

The Great Depression

Herbert Hoover (President during the Depression) his view on the role of the government in the economy. Helps to explain why the Depression happened and why he was so slow to act.

Herbert Hoover, “Principles and Ideals of the United States Government,” Speech, (October 22, 1928). Available online via http://millercenter.org/president/hoover/speeches/speech-6000.

A simplified explanation of the causes of the stock market crash of 1929

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s3CBVQenfvA

Imoxxchat (November 27, 2016). The Stock Market Crash of 1929 Causes and Effects. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s3CBVQenfvA

Summary

The Great Depression was the confluence of many problems, most of which had begun during a time of unprecedented economic growth. Fiscal policies of the Republican “business presidents” undoubtedly widened the gap between rich and poor and fostered a “stand-off” over international trade, but such policies were popular and, for much of the decade, widely seen as a source of the decade’s explosive growth. The expansion of industry and credit allowed more Americans to take part in an expanding consumer society. With fortunes to be won and standards of living to maintain, few Americans had the foresight or wherewithal to repudiate an age of easy credit, rampant consumerism, and wild speculation.

When the stock market crashed in late October 1929, the American people and the federal government were caught off guard and ill prepared to deal with the fallout. Americans panicked, pulling what little money was left out of banks causing rampant bank failure.

Hoover, the pro-business Republican president, looked to businesses to voluntarily maintain investments and employment levels. As he believed direct aid was not the role of the federal government, he encouraged state and local charities to provide relief to the growing number of unemployed. Thus, the early years of the Depression were catastrophic. The crisis, far from relenting, deepened each year. Unemployment peaked at 25% in 1932. This was combined with the Great Plains region being literally blown away in dust storms resulting from decades of agricultural mismanagement, extending the troubles of the Depression even deeper into rural America. With no end in sight, and with private firms crippled and charities overwhelmed by the crisis, Americans looked to their government as the last barrier against starvation, hopelessness, and perpetual poverty.