32

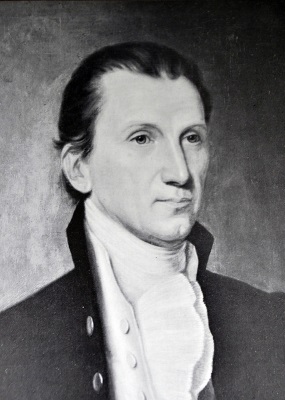

When a wave of rebellion spread across Spain’s Latin American colonies in the second decade of the 19th century, Americans were sympathetic to the efforts of a colonized people to break away from their European colonizer. As these former colonies began to form their own independent governments, President James Monroe’s administration became the first government to extend diplomatic recognition to these new Latin American nations. The United States was far too familiar with the efforts of European nations to draw economic gain at the expense of their American colonies. The Monroe administration saw both diplomatic and economic opportunity in an independent Western Hemisphere.

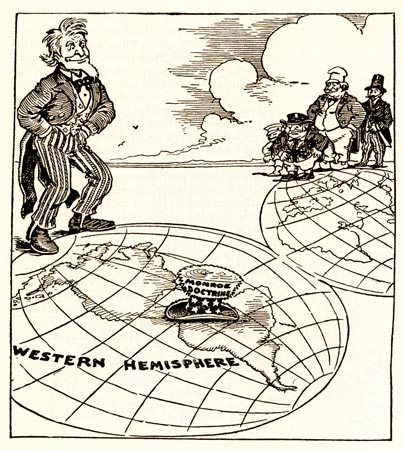

The American foreign policy that emerged in response to this wave of Latin American independence came to be called the Monroe Doctrine. The Monroe Doctrine is sometimes referred to as America’s diplomatic declaration of independence. This statement of foreign policy delivered in a speech to Congress in 1823 came at a moment in which the United States looked to continue to expand its international trade and assert itself as the dominant power in the Western Hemisphere.

Written by Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, the Monroe Doctrine outlined three principles for American foreign policy. The first two were aimed at asserting American power within the hemisphere. The United States declared that it would oppose any further colonization efforts by European powers and that it would defend the newly independent Latin American states against any European intervention. In return, the United States would not involve itself in European conflicts.

The Monroe Doctrine represented America’s break from Europe diplomatically as it was a recognition that American interests were different from those of the European powers. But of greater consequence to the coming decades, it also represented American expansion. As America expanded economically and geographically in the first several decades of the 19th century, there was a growing nationalism focused on the potential power of the United States in the hemisphere and on the world stage.

The Monroe Doctrine and Manifest Destiny

Expansion of influence and territory off the continent became an important corollary to westward expansion. One of the main goals of the U.S. government was the prevention of outside involvement of European countries in the affairs of the western hemisphere. American policymakers sought an outlet for the domestic assertions of manifest destiny in the nation’s early foreign policy decisions of the antebellum period.

As Secretary of State for President James Monroe, John Quincy Adams held the responsibility for the satisfactory resolution of ongoing border disputes in different areas of North America between the United States, England, Spain, and Russia. Adams was a proponent of both the concept of continentalism and an American influence in hemispheric events. Adams’ comprehensive view of American policy aims was put into clearest practice in the Monroe Doctrine, which he had great influence in crafting.

Increasingly aggressive incursions from the Russians in the Northwest, ongoing border disputes with the British in Canada, the remote possibility of Spanish reconquest of South America, and British abolitionism in their Caribbean colonies all forced a U.S. response to the threats encircling the country. However, despite the philosophical confidence present in the Monroe administration’s decree, the reality of limited military power kept the Monroe Doctrine as an aspirational assertion that many in the administration and the country believed the United States would grow into as it matured. Secretary of State Adams acknowledged the American need for a robust foreign policy that simultaneously protected and encouraged the growing and increasingly dynamic capitalist orientation of the country in a speech before the U.S. House of Representatives on July 4th, 1821.

America…in the lapse of nearly half a century, without a single exception, respected the independence of other nations while asserting and maintaining her own…She is the well-wisher to the freedom and independence of all. She is the champion and vindicator only of her own. She will commend the general cause by the countenance of her voice, and the benignant sympathy of her example. She well knows that by once enlisting under other banners than her own, were they even the banners of foreign independence, she would involve herself beyond the power of extrication, in all the wars of interest and intrigue, of individual avarice, envy, and ambition, which assume the colors and usurp the standard of freedom. The fundamental maxims of her policy would insensibly change from liberty to force. The frontlet on her brows would no longer beam with the ineffable splendor of freedom and independence; but in its stead would soon be substituted an imperial diadem, flashing in false and tarnished lustre the murky radiance of dominion and power. She might become the dictatress of the world; she would be no longer the ruler of her own spirit. . . . Her glory is not dominion, but liberty. Her march is the march of the mind. She has a spear and a shield: but the motto upon her shield is, Freedom, Independence, Peace. This has been her Declaration: this has been, as far as her necessary intercourse with the rest of mankind would permit, her practice.

—John Quincy Adams

However, Adams’ great fear was not territorial loss. He had no doubt that Russian and British interests in North America could be arrested. Adams held no reason to antagonize the Russians with grand pronouncements nor was he generally called upon to do so. He enjoyed a good relationship with the Russian Ambassador and stewarded through Congress most-favored trade status for the Russians in 1824. Rather, Adams worried gravely about the ability of the United States to compete commercially with the British in Latin America and the Caribbean. This concern deepened with the valid concern that America’s chief Latin American trading partner, Cuba, dangled perilously close to outstretched British claws. The Cabinet debates surrounding establishment of the Monroe Doctrine, the international diplomacy undertaken by Adams and his underlings, and geopolitical events in the Caribbean focused attention on that part of the world as key to the future defense of U.S. military and commercial interests with the main threat to those interests being the British. Expansion of economic opportunity and protection of American society and markets from foreign pressures became the overriding goals of U.S. foreign policy.

Bitter disagreements over the expansion of slavery into what became the Mexican Cession territory began even before the Mexican war ended. Many Northern business and Southern slaveowners supported the idea of expansion of American power and slavery into the Caribbean as a useful alternative to continental expansion since slavery already existed in these areas. While some were critical of these attempts, seeing them as evidence of a growing slave-power conspiracy, many supported these extra-legal attempts at expansion. Filibustering, as it was called, was privately financed schemes of varying degrees of operational reality directed at capturing and occupying foreign territory without the approval of the U.S. government.

Filibustering adventures took greatest hold in the imagination of Americans as they looked toward Cuba with particular interest. Fears of racialized revolution in Cuba (as in Haiti before it) as well as the presence of an aggressive British abolitionary influence in the Caribbean energized the movement to annex Cuba and encouraged filibustering activities as expedient alternatives to lethargic official negotiations. Despite filibustering’s seemingly chaotic planning and destabilizing repercussions, those intellectually and economically guiding the effort saw in their efforts a willing and receptive Cuban population and an agreeable American business class. In Cuba, manifest destiny for the first time sought territory off the continent and hoped to put a unique spin on the story of success in Mexico. Yet, the annexation of Cuba, despite great popularity and some military attempts led by Narciso Lopez (pictured), a Cuban dissident, never succeeded.

Regardless of that disappointment planning and action against other areas took place. Most notable among these efforts was William Walker’s momentarily successful filibustering against Nicaragua. Walker, who was a long-time filibusterer, launched several expeditions in Mexico and Central America and achieved success in establishing his rule and slavery on the Nicaraguan coast before eventually being executed, with British encouragement, in Honduras. Although these mission enjoyed neither the support of the law or the U.S. government, wealthy Americans financed various filibusters and less-wealthy adventurers were all to happy to sign up. Filibustering enjoyed its brief popularity into the late 1850s, at which point slavery and concerns over session came to the fore. By the opening of the Civil War most saw these attempts as simply territorial theft and muscular articulations of individual desires toward profit and dominance. Caribbean expansion, now predicated on the reinvigoration of slavery through filibustering, seemed anathema to the American democratic disposition.

One of the last pieces of manifest destiny’s collapse was the economic fracturing of the regions of the United States. The national economic market steadily weakened as a unifying entity after 1857 when the South finally received some tangible demonstration of the superiority of their economic project. They emerged from the Panic of 1857 with the sense that the North needed Southern commerce more than the South needed Northern industry. The South embraced this evidence and the resultant increase in its confidence as they suffered under the presumption that Northern dominance might never relent. The confidence gained through lucrative business relations with world markets, the diversification of the Southern manufacturing base, the relatively light toll taken by the Panic of 1857, the possibility of Cuban annexation, the dominance of presidential elections in the 1850s, and the political capitulation of Northern interests in the tariff debate of 1858 all led the South toward a belief in the political possibility of secession and the likelihood of success.

Throughout the antebellum period slavery continuously expanded onto new ground, embracing new crops, and new machinery. The planter class throughout the United States, the Caribbean, and South America exerted a political and economic dominance in rising world markets and their national political cultures that made the continued existence of slavery the foundation of their power. Yet, profits gained in the sugar, coffee, and cotton areas also depended on a complex economic and industrial partnership between non-slave owning business/production entities and slaveholding agriculturalists. The entire undertaking of the Atlantic economy fueled American growth and drove the confidence and economic funding required for the completion of manifest destiny’s expansion. Workers and financiers, slaves and settlers, planters and industrialists all produced, willingly or forced, the economic juggernaut that, while encouraging American expansion, also became a part of its undoing.

Attribution:

Lumen: US History I (AY Collection). (n.d.) The Monroe Doctrine and Manifest Destiny. Retrieved from https://courses.lumenlearning.com/ushistory1ay/chapter/the-monroe-doctrine-and-manifest-destiny/

President Monroe Outlines the Monroe Doctrine, 1823

The spirit of Manifest Destiny had its corollary in an earlier piece of American foreign policy. Americans sought to remove colonizing Europeans from the western hemisphere. As Secretary of State for President James Monroe, John Quincy Adams crafted what came to be called the Monroe Doctrine. President Monroe outlined the principles of this policy in his seventh annual message to Congress, excerpted here.

… At the proposal of the Russian Imperial Government, made through the minister of the Emperor residing here, a full power and instructions have been transmitted to the minister of the United States at St. Petersburg to arrange by amicable negotiation the respective rights and interests of the two nations on the northwest coast of this continent. A similar proposal has been made by His Imperial Majesty to the Government of Great Britain, which has likewise been acceded to. The Government of the United States has been desirous by this friendly proceeding of manifesting the great value which they have invariably attached to the friendship of the Emperor and their solicitude to cultivate the best understanding with his Government. In the discussions to which this interest has given rise and in the arrangements by which they may terminate the occasion has been judged proper for asserting, as a principle in which the rights and interests of the United States are involved, that the American continents, by the free and independent condition which they have assumed and maintain, are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European powers. . .It was stated at the commencement of the last session that a great effort was then making in Spain and Portugal to improve the condition of the people of those countries, and that it appeared to be conducted with extraordinary moderation. It need scarcely be remarked that the results have been so far very different from what was then anticipated. Of events in that quarter of the globe, with which we have so much intercourse and from which we derive our origin, we have always been anxious and interested spectators. The citizens of the United States cherish sentiments the most friendly in favor of the liberty and happiness of their fellow-men on that side of the Atlantic. In the wars of the European powers in matters relating to themselves we have never taken any part, nor does it comport with our policy to do so. It is only when our rights are invaded or seriously menaced that we resent injuries or make preparation for our defense. With the movements in this hemisphere we are of necessity more immediately connected, and by causes which must be obvious to all enlightened and impartial observers. The political system of the allied powers is essentially different in this respect from that of America. This difference proceeds from that which exists in their respective Governments; and to the defense of our own, which has been achieved by the loss of so much blood and treasure, and matured by the wisdom of their most enlightened citizens, and under which we have enjoyed unexampled felicity, this whole nation is devoted. We owe it, therefore, to candor and to the amicable relations existing between the United States and those powers to declare that we should consider any attempt on their part to extend their system to any portion of this hemisphere as dangerous to our peace and safety. With the existing colonies or dependencies of any European power we have not interfered and shall not interfere. But with the Governments who have declared their independence and maintain it, and whose independence we have, on great consideration and on just principles, acknowledged, we could not view any interposition for the purpose of oppressing them, or controlling in any other manner their destiny, by any European power in any other light than as the manifestation of an unfriendly disposition toward the United States. In the war between those new Governments and Spain we declared our neutrality at the time of their recognition, and to this we have adhered, and shall continue to adhere, provided no change shall occur which, in the judgment of the competent authorities of this Government, shall make a corresponding change on the part of the United States indispensable to their security.

The late events in Spain and Portugal shew that Europe is still unsettled. Of this important fact no stronger proof can be adduced than that the allied powers should have thought it proper, on any principle satisfactory to themselves, to have interposed by force in the internal concerns of Spain. To what extent such interposition may be carried, on the same principle, is a question in which all independent powers whose governments differ from theirs are interested, even those most remote, and surely none of them more so than the United States. Our policy in regard to Europe, which was adopted at an early stage of the wars which have so long agitated that quarter of the globe, nevertheless remains the same, which is, not to interfere in the internal concerns of any of its powers; to consider the government de facto as the legitimate government for us; to cultivate friendly relations with it, and to preserve those relations by a frank, firm, and manly policy, meeting in all instances the just claims of every power, submitting to injuries from none. But in regard to those continents circumstances are eminently and conspicuously different.

It is impossible that the allied powers should extend their political system to any portion of either continent without endangering our peace and happiness; nor can anyone believe that our southern brethren, if left to themselves, would adopt it of their own accord. It is equally impossible, therefore, that we should behold such interposition in any form with indifference. If we look to the comparative strength and resources of Spain and those new Governments, and their distance from each other, it must be obvious that she can never subdue them. It is still the true policy of the United States to leave the parties to themselves, in hope that other powers will pursue the same course. . . .

Message of President James Monroe at the commencement of the first session of the 18th Congress, 12/02/1823; Presidential Messages of the 18th Congress, ca. 12/02/1823-ca. 03/03/1825; Record Group 46; Records of the United States Senate, 1789-1990; National Archives.

Available through the National Archives and Records Administration

Attribution:

Message of President James Monroe at the commencement of the first session of the 18th Congress, 12/02/1823; Presidential Messages of the 18th Congress, ca. 12/02/1823-ca. 03/03/1825; Record Group 46; Records of the United States Senate, 1789-1990; National Archives.

What Is The Monroe Doctrine?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=628cN6vvmKs

Attribution:

The Audiopedia. (February 22, 2017). What is Monroe Doctrine? [Video File] Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=628cN6vvmKs

The Monroe Doctrine

Attribution:

Khan Academy. (nd). The Monroe Doctrine. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ap-us-history/period-4/apush-politics-society-early-19th-c/v/the-monroe-doctrine

Summary

The Monroe Doctrine emerged at a moment of expansion in the United States. The first several decades of the century saw a Market Revolution. This was a revolution in the American economy as industry and markets expanded to take advantage of the new territory acquired as a result of the Louisiana Purchase. The result was Americans moving westward across the continent taking with them their political, economic and social ideals. While this eventually caused bitter sectional disagreements that eventually resulted in the Civil War, the majority of Americans could agree on the idea that it was America’s Manifest Destiny to expand westward.

Manifest Destiny was the belief that it was America’s destiny to continue to expand westward. This idea was intertwined with the growing nationalist sentiment. This nationalism and belief in America’s destiny to expand are both reflected in the Monroe Doctrine. While Manifest Destiny was an idea rather than a political policy like the Monroe Doctrine, both were used to justify American territorial expansion within the western hemisphere.

At its moment, the Monroe Doctrine expressed somewhat conflicting ideas about America’s role in the world. On the one hand it was used as a justification for expanding American territory. But at the same time it declared that America would not get involved in events across the Atlantic, a more isolationist stance. In the years immediately following, the Monroe Doctrine had limited effect on America’s global influence, but by the 20th century the Monroe Doctrine was reinterpreted as an expression of America’s intention to be an influential player on the world stage.