16

In the decades following the Civil War, the United States emerged as an industrial giant. Old industries expanded and many new ones, including petroleum refining, steel manufacturing, and electrical power, emerged. Railroads expanded significantly, bringing even remote parts of the country into a national market economy.

Industrial growth transformed American society. It produced a new class of wealthy industrialists and a prosperous middle class. It also produced a vastly expanded blue collar working class. The labor force that made industrialization possible was made up of millions of newly arrived immigrants and even larger numbers of migrants from rural areas. American society became more diverse than ever before.

Not everyone shared in the economic prosperity of this period. Many workers were typically unemployed at least part of the year, and their wages were relatively low when they did work. This situation led many workers to support and join labor unions. Meanwhile, farmers also faced hard times as technology and increasing production led to more competition and falling prices for farm products. Hard times on farms led many young people to move to the city in search of better job opportunities.

The Rise of Industrial America

Industrialization and Technological Innovation

The late nineteenth century was an energetic era of inventions and entrepreneurial spirit. Building upon the mid-century Industrial Revolution in Great Britain, as well as answering the increasing call from Americans for efficiency and comfort, the country found itself in the grip of invention fever, with more people working on their big ideas than ever before. In retrospect, harnessing the power of steam and then electricity in the nineteenth century vastly increased the power of man and machine, thus making other advances possible as the century progressed.

Facing an increasingly complex everyday life, Americans sought the means by which to cope with it. Inventions often provided the answers, even as the inventors themselves remained largely unaware of the life-changing nature of their ideas. To understand the scope of this zeal for creation, consider the U.S. Patent Office, which, in 1790—its first decade of existence—recorded only 276 inventions. By 1860, the office had issued a total of 60,000 patents. But between 1860 and 1890, that number exploded to nearly 450,000, with another 235,000 in the last decade of the century. While many of these patents came to naught, some inventions became lynchpins in the rise of big business and the country’s move towards an industrial-based economy, in which the desire for efficiency, comfort, and abundance could be more fully realized by most Americans.

From corrugated rollers that could crack hard, homestead-grown wheat into flour to refrigerated train cars and garment-sewing machines new inventions fueled industrial growth around the country. As late as 1880, fully one-half of all Americans still lived and worked on farms, whereas fewer than one in seven—mostly men, except for long-established textile factories in which female employees tended to dominate—were employed in factories. However, the development of commercial electricity by the close of the century, to complement the steam engines that already existed in many larger factories, permitted more industries to concentrate in cities, away from the previously essential water power. In turn, newly arrived immigrants sought employment in new urban factories. Immigration, urbanization, and industrialization coincided to transform the face of American society from primarily rural to significantly urban. From 1880 to 1920, the number of industrial workers in the nation quadrupled from 2.5 million to over 10 million, while over the same period urban populations doubled, to reach one-half of the country’s total population.

In offices, worker productivity benefited from the typewriter, invented in 1867, the cash register, invented in 1879, and the adding machine, invented in 1885. These tools made it easier than ever to keep up with the rapid pace of business growth. Inventions also slowly transformed home life. The vacuum cleaner arrived during this era, as well as the flush toilet. These indoor “water closets” improved public health through the reduction in contamination associated with outhouses and their proximity to water supplies and homes. Tin cans and, later, Clarence Birdseye’s experiments with frozen food, eventually changed how women shopped for, and prepared, food for their families, despite initial health concerns over preserved foods. With the advent of more easily prepared food, women gained valuable time in their daily schedules, a step that partially laid the groundwork for the modern women’s movement. Women who had the means to purchase such items could use their time to seek other employment outside of the home, as well as broaden their knowledge through education and reading. Such a transformation did not occur overnight, as these inventions also increased expectations for women to remain tied to the home and their domestic chores; slowly, the culture of domesticity changed.

Perhaps the most important industrial advancement of the era came in the production of steel. Manufacturers and builders preferred steel to iron, due to its increased strength and durability. After the Civil War, two new processes allowed for the creation of furnaces large enough and hot enough to melt the wrought iron needed to produce large quantities of steel at increasingly cheaper prices. The Bessemer process, named for English inventor Henry Bessemer, and the open-hearth process, changed the way the United States produced steel and, in doing so, led the country into a new industrialized age. As the new material became more available, builders eagerly sought it out, a demand that steel mill owners were happy to supply.

In 1860, the country produced thirteen thousand tons of steel. By 1879, American furnaces were producing over one million tons per year; by 1900, this figure had risen to ten million. Just ten years later, the United States was the top steel producer in the world, at over twenty-four million tons annually. As production increased to match the overwhelming demand, the price of steel dropped by over 80 percent. When quality steel became cheaper and more readily available, other industries relied upon it more heavily as a key to their growth and development, including construction and, later, the automotive industry. As a result, the steel industry rapidly became the cornerstone of the American economy, remaining the primary indicator of industrial growth and stability through the end of World War II.

From Invention to Industrial Growth

New processes in steel refining, along with inventions in the fields of communications and electricity, transformed the business landscape of the nineteenth century. The exploitation of these new technologies provided opportunities for tremendous growth, and business entrepreneurs with financial backing and the right mix of business acumen and ambition could make their fortunes. Some of these new millionaires were known in their day as robber barons, a negative term that connoted the belief that they exploited workers and bent laws to succeed. Regardless of how they were perceived, these businessmen and the companies they created revolutionized American industry.

Earlier in the nineteenth century, the first transcontinental railroad and subsequent spur lines paved the way for rapid and explosive railway growth, as well as stimulated growth in the iron, wood, coal, and other related industries. The railroad industry quickly became the nation’s first “big business.” A powerful, inexpensive, and consistent form of transportation, railroads accelerated the development of virtually every other industry in the country. By 1890, railroad lines covered nearly every corner of the United States, bringing raw materials to industrial factories and finished goods to consumer markets. The amount of track grew from 35,000 miles at the end of the Civil War to over 200,000 miles by the close of the century. Inventions such as car couplers, air brakes, and Pullman passenger cars allowed the volume of both freight and people to increase steadily. From 1877 to 1890, both the amount of goods and the number of passengers traveling the rails tripled.

Financing for all of this growth came through a combination of private capital and government loans and grants. Federal and state loans of cash and land grants totaled $150 million and 185 million acres of public land, respectively. Railroads also listed their stocks and bonds on the New York Stock Exchange to attract investors from both within the United States and Europe. Individual investors consolidated their power as railroads merged and companies grew in size and power. These individuals became some of the wealthiest Americans the country had ever known. Midwest farmers, angry at large railroad owners for their exploitative business practices, came to refer to them as “robber barons,” as their business dealings were frequently shady and exploitative. Among their highly questionable tactics was the practice of differential shipping rates, in which larger business enterprises received discounted rates to transport their goods, as opposed to local producers and farmers whose higher rates essentially subsidized the discounts.

Jay Gould was perhaps the first prominent railroad magnate to be tarred with the “robber baron” brush. He bought older, smaller, rundown railroads, offered minimal improvements, and then capitalized on factory owners’ desires to ship their goods on this increasingly popular and more cost-efficient form of transportation. His work with the Erie Railroad was notorious among other investors, as he drove the company to near ruin in a failed attempt to attract foreign investors during a takeover attempt. His model worked better in the American West, where the railroads were still widely scattered across the country, forcing farmers and businesses to pay whatever prices Gould demanded in order to use his trains. In addition to owning the Union Pacific Railroad that helped to construct the original transcontinental railroad line, Gould came to control over ten thousand miles of track across the United States, accounting for 15 percent of all railroad transportation. When he died in 1892, Gould had a personal worth of over $100 million, although he was a deeply unpopular figure.

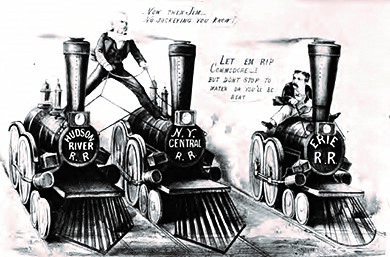

In contrast to Gould’s exploitative business model, which focused on financial profit more than on tangible industrial contributions, Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt was a “robber baron” who truly cared about the success of his railroad enterprise and its positive impact on the American economy. Vanderbilt consolidated several smaller railroad lines, called trunk lines, to create the powerful New York Central Railroad Company, one of the largest corporations in the United States at the time (Figure). He later purchased stock in the major rail lines that would connect his company to Chicago, thus expanding his reach and power while simultaneously creating a railroad network to connect Chicago to New York City. This consolidation provided more efficient connections from Midwestern suppliers to eastern markets. It was through such consolidation that, by 1900, seven major railroad tycoons controlled over 70 percent of all operating lines. Vanderbilt’s personal wealth at his death (over $100 million in 1877), placed him among the top three wealthiest individuals in American history.

New American Consumer Culture

Despite the challenges workers faced in their new roles as wage earners, the rise of industry in the United States allowed people to access and consume goods as never before. The rise of big business had turned America into a culture of consumers desperate for time-saving and leisure commodities, where people could expect to find everything they wanted in shops or by mail order. Gone were the days where the small general store was the only option for shoppers; at the end of the nineteenth century, people could take a train to the city and shop in large department stores like Macy’s in New York, Gimbel’s in Philadelphia, and Marshall Field’s in Chicago. Chain stores, like A&P and Woolworth’s, both of which opened in the 1870s, offered options to those who lived farther from major urban areas and clearly catered to classes other than the wealthy elite. Industrial advancements contributed to this proliferation, as new construction techniques permitted the building of stores with higher ceilings for larger displays, and the production of larger sheets of plate glass lent themselves to the development of larger store windows, glass countertops, and display cases where shoppers could observe a variety of goods at a glance. L. Frank Baum, of Wizard of Oz fame, later founded the National Association of Window Trimmers in 1898, and began publishing The Store Window journal to advise businesses on space usage and promotion.

Even families in rural America had new opportunities to purchase a greater variety of products than ever before, at ever decreasing prices. Those far from chain stores could benefit from the newly developed business of mail-order catalogs, placing orders by telephone. Aaron Montgomery Ward established the first significant mail-order business in 1872, with Sears, Roebuck & Company following in 1886. Sears distributed over 300,000 catalogs annually by 1897, and later broke the one million annual mark in 1907. Sears in particular understood that farmers and rural Americans sought alternatives to the higher prices and credit purchases they were forced to endure at small-town country stores. By clearly stating the prices in his catalog, Richard Sears steadily increased his company’s image of their catalog serving as “the consumer’s bible.” In the process, Sears, Roebuck & Company supplied much of America’s hinterland with products ranging from farm supplies to bicycles, toilet paper to automobiles, as seen below in a page from the catalog.

The tremendous variety of goods available for sale required businesses to compete for customers in ways they had never before imagined. Suddenly, instead of a single option for clothing or shoes, customers were faced with dozens, whether ordered by mail, found at the local chain store, or lined up in massive rows at department stores. This new level of competition made advertising a vital component of all businesses. By 1900, American businesses were spending almost $100 million annually on advertising. Competitors offered “new and improved” models as frequently as possible in order to generate interest. From toothpaste and mouthwash to books on entertaining guests, new goods were constantly offered. Newspapers accommodated the demand for advertising by shifting their production to include full-page advertisements, as opposed to the traditional column width, agate-type advertisements that dominated mid-nineteenth century newspapers (similar to classified advertisements in today’s publications). Likewise, professional advertising agencies began to emerge in the 1880s, with experts in consumer demand bidding for accounts with major firms.

It may seem strange that, at a time when wages were so low, people began buying readily; however, the slow emergence of a middle class by the end of the century, combined with the growing practice of buying on credit, presented more opportunities to take part in the new consumer culture. Stores allowed people to open accounts and purchase on credit, thus securing business and allowing consumers to buy without ready cash. Then, as today, the risks of buying on credit led many into debt. As advertising expert Roland Marchand described in his Parable on the Democracy of Goods, in an era when access to products became more important than access to the means of production, Americans quickly accepted the notion that they could live a better lifestyle by purchasing the right clothes, the best hair cream, and the shiniest shoes, regardless of their class. For better or worse, American consumerism had begun.

Attribution:

American Yawp. Licensed under CC BY SA 4.0 https://cnx.org/contents/p7ovuIkl@3.84:RVq_sKVC@3/From-Invention-to-Industrial-G

https://cnx.org/contents/p7ovuIkl@3.84:gCq9MMH8@3/A-New-American-Consumer-Cultur

Summary

Americans who were born in the 1840s and 1850s would experience enormous changes in their lifetimes. Some of these changes resulted from a sweeping technological revolution. Their major source of light, for example, would change from candles, to kerosene lamps, and then to electric light bulbs. They would see their transportation evolve from walking and horse power to steam-powered locomotives, to electric trolley cars, to gasoline-powered automobiles. Born into a society in which the vast majority of people were involved in agriculture, they experienced an industrial revolution that radically changed the ways millions of people worked and where they lived. They would experience the migration of millions of people from rural America to the nation’s rapidly growing cities.