23

The women’s rights movement marks its official beginning in 1848 under the leadership of Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Using the Declaration of Independence as their model, these early activists drafted the Declaration of Sentiments outlining the areas of life where they believed there existed unjust treatment of women. Following the first women’s rights convention at Seneca Falls, New York in 1848, the movement continued to grow and additional conventions were held. Throughout the remainder 19th century women continued to advocate for equality in the workplace, in marriage, in church-related affairs, and, ultimately, in the right to vote.

As pressure grew at the turn-of-the-century to gain the right to vote, division also grew within the women’s rights movement on how to go about advocating for that right. Carrie Chapman Catt, the president of the National Women’s Suffrage Association (NWSA), organized a nationwide campaign to inundate government officials to support suffrage for women. Alice Paul, a founder of the National Women’s Party, considered the radical wing of the movement, utilized more militant tactics. The NWP organized marches, protests outside the White House and hunger strikes. Ida B. Wells argued that black women were being left out of the equation and fought for inclusion in the nationwide movement for women.

Other milestones in the movement included the Supreme Court declassifying birth control information as obscene (although it will take until 1960 for the Food and Drug Administration to approve birth control pills). Margaret Sanger founded the American Birth Control League (which evolved into Planned Parenthood in 1942). In 1935 Mary McLeod Bethune organized the National Council on Negro Women to lobby against job discrimination, racism, and sexism.

What is considered the second wave of the women’s rights movement began in the 1960s. President John F. Kennedy convened a Commission on the Status of Women and in 1963, with Eleanor Roosevelt as its chair, they issued a report documenting the discrimination against women in almost every aspect of life. That same year, Betty Friedan published her book The Feminine Mystique, which inspired women to move beyond their role as a homemaker and fulfill their dreams. As part of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission was established to investigate discrimination based on race or sex. And in 1966, the National Organization for Women (NOW) kicked off the establishment of an array of organizations geared toward addressing the needs of specific groups of women (black women, women in sports, women in politics, Asian-American women, Latinas, business owners, etc.). And in 1972, Title XI was included in a new law targeting higher education and equal access for women.

In 1971, Ms. Magazine was first published as a sample insert in New York magazine launching Gloria Steinem, its co-founder and editor, as an icon of the modern feminist movement. While the passage of an Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) in 1972 seemed a foregone conclusion, the campaign for its passage met with resistance from an unlikely source: other women. Led by Phyllis Schlafly, women who feared the erosion of the family, gay marriage, and women being drafted were given lopsided attention in contrast to their more progressive counterparts. Ultimately, the ERA fell 3 states shy of ratification in 1982. In the meantime, the Supreme Court decision in Roe v. Wade in 1973 established women’s right to a safe and legal abortion.

Women’s Movements

Women’s clubs flourished in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. In 1890s women formed national women’s club federations. Particularly significant in campaigns for suffrage and women’s rights were the General Federation of Women’s Clubs (formed in New York City in 1890) and the National Association of Colored Women (organized in Washington, D.C., in 1896), both of which were dominated by upper-middle-class, educated, northern women. Few of these organizations were bi-racial, a legacy of the sometimes uneasy mid-nineteenth-century relationship between socially active African Americans and white women. Rising American prejudice led many white female activists to ban inclusion of their African American sisters. The segregation of black women into distinct clubs nonetheless still produced vibrant organizations that could promise racial uplift and civil rights for all blacks, as well as equal rights for women.

Other women worked through churches and moral reform organizations to clean up American life. And still others worked as moral vigilantes. The fearsome Carrie A. Nation, an imposing woman who believed she worked God’s will, won headlines for destroying saloons. In Wichita, Kansas, on December 27, 1900, Nation took a hatchet and broke bottles and bars at the luxurious Carey Hotel. Arrested and charged with $3000 in damages, Nation spent a month in jail before the county dismissed the charges on account of “a delusion to such an extent as to be practically irresponsible.” But Nation’s “hatchetation” drew national attention. Describing herself as “a bulldog running along at the feet of Jesus, barking at what He doesn’t like,” she continued her assaults, and days later smashed two more Wichita bars.

Few women followed in Nation’s footsteps, and many more worked within more reputable organizations. Nation, for instance, had founded a chapter of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, (WCTU) but the organizations’ leaders described her as “unwomanly and unchristian.” The WCTU was founded in 1874 as a modest temperance organization devoted to combatting the evils of drunkenness. But then, from 1879 to 1898, Frances Willard invigorated the organization by transforming it into a national political organization, embracing a “do everything” policy that adopted any and all reasonable reforms that would improve social welfare and advance women’s rights. Temperance, and then the full prohibition of alcohol, however, always loomed large.

Many American reformers associated alcohol with nearly every social ill. Alcohol was blamed for domestic abuse, poverty, crime, and disease. The 1912 Anti-Saloon League Yearbook, for instance, presented charts indicating comparable increases in alcohol consumption alongside rising divorce rates. The WCTU called alcohol a “home wrecker.” More insidiously, perhaps, reformers also associated alcohol with cities and immigrants, necessarily maligning America’s immigrants, Catholics, and working classes in their crusade against liquor. Still, reformers believed that the abolition of “strong drink” would bring about social progress, would obviate the need for prisons and insane asylums, would save women and children from domestic abuse, and usher in a more just, progressive society.

From the club movement and temperance campaigns emerged powerful, active, female activists. Perhaps no American reformer matched Jane Addams’ in fame, energy, and innovation. Born in Cedarville, Illinois, in 1860, Addams lost her mother by the age of two and lived under the attentive care of her father. At seventeen, she left home to attend Rockford Female Seminary. An idealist, Addams sought the means to make the world a better place. She believed that well-educated women of means, such as herself, lacked practical strategies for engaging everyday reform. After four years at Rockford, Addams embarked upon on a multi-year “grand tour” of Europe. Jane found herself drawn to English settlement houses, a kind of prototype for social work in which philanthropists embedded themselves among communities and offered services to disadvantaged populations. After visiting London’s Toynbee Hall in 1887, Addams returned to the US and in 1889 founded Hull House in Chicago with her longtime confidant and companion Ellen Gates Starr.

Hull House workers provided for their neighbors by running a nursery and a kindergarten, administering classes for parents and clubs for children, and organizing social and cultural events for the community. Florence Kelley stayed at Hull House from 1891 to 1899, taking the settlement house model to New York and founding the Henry Street Settlement there. But Kelley also influenced Addams, convincing her to move into the realm of social reform.13 Hull House began exposing conditions in local sweat shops and advocating for the organization of workers. She called the conditions caused by urban poverty and industrialization a “social crime.” Hull House workers surveyed their community and produced statistics of poverty, disease, and living conditions that proved essential for reformers. Addams began pressuring politicians. Together Kelley and Addams petitioned legislators to pass anti-sweatshop legislation passed that limited the hours of work for women and children to eight per day. Yet Addams was an upper class white Protestant woman who had faced limits, like many reformers, in embracing what seemed to them radical policies. While Addams called labor organizing a “social obligation,” she also warned the labor movement against the “constant temptation towards class warfare.” Addams, like many reformers, favored cooperation between rich and poor and bosses and workers, whether cooperation was a realistic possibility or not.

Addams became a kind of celebrity. In 1912, she became the first woman to give a nominating speech at a major party convention when she seconded the nomination of Theodore Roosevelt as the Progressive Party’s candidate for president. Her campaigns for social reform and women’s rights won headlines and her voice became ubiquitous in progressive politics.

Addams’ concerns grew beyond domestic concerns. Beginning with her work in the Anti-Imperialist League during the Spanish-American War Addams increasingly began to see militarism as a drain on resources better spent on social reform. In 1907 she wrote Newer Ideals of Peace, a book that would become for many a philosophical foundation of pacifism. Addams emerged as a prominent opponent of America’s entry into World War I. She received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931.

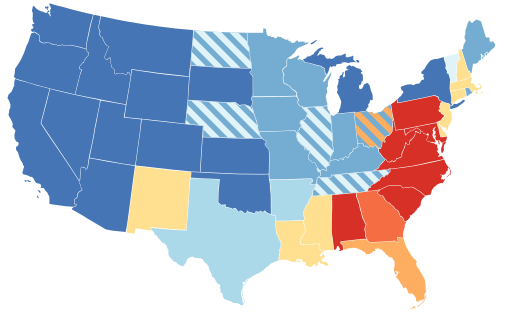

It would be suffrage, ultimately, that would mark the full emergence of women in American public life. Generations of women—and, occasionally, men—had pushed for women’s suffrage. Suffragists’ hard work resulted in slow but encouraging steps forward during the last decades of the nineteenth century. Notable victories were won in the West, where suffragists mobilized large numbers of women and male politicians were open to experimental forms of governance. By 1911, six western states had passed suffrage amendments to their constitutions.

Women’s suffrage was typically entwined with a wide range of reform efforts. Many suffragists argued that women’s votes were necessary to clean up politics and combat social evils. By the 1890s, for example, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, then the largest women’s organization in America, endorsed suffrage. An alliance of working-class and middle- and upper-class women organized the Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL) in 1903 and campaigned for the vote alongside the National American Suffrage Association, a leading suffrage organization comprised largely of middle and upper-class women. WTUL members viewed the vote as a way to further their economic interests and to foster a new sense of respect for working-class women. “What the woman who labors wants is the right to live, not simply exist,” said Ruth Schneiderman, a WTUL leader, during a 1912 speech. “The worker must have bread, but she must have roses, too.”17

Many suffragists adopted a much crueler message. Some, even outside of the South, argued that white women’s votes were necessary to maintain white supremacy. Many American women found it advantageous to base their arguments for the vote on the necessity of maintaining white supremacy by enfranchising white, upper and middle class women. These arguments even stretched into international politics. But whatever the message, the suffrage campaign was winning.

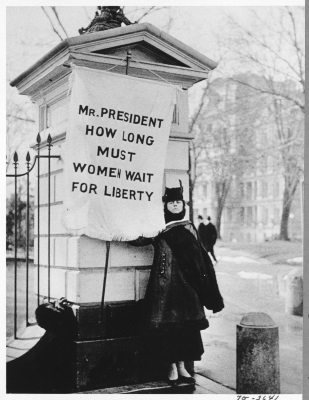

The final push for women’s suffrage came on the eve of World War I. Determined to win the vote; the National American Suffrage Association developed a dual strategy that focused on the passage of state voting rights laws and on the ratification of an amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Meanwhile, a new, more militant, suffrage organization emerged on the scene. Led by Alice Paul, the National Women’s Party took to the streets to demand voting rights, organizing marches and protests that mobilized thousands of women. Beginning in January 1917, National Women’s Party members also began to picket the White House, an action that led to the arrest and imprisonment of over 150 women.

In January 1918, President Woodrow Wilson declared his support for the women’s suffrage amendment and, two years later women’s suffrage became a reality. After the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, women from all walks of life mobilized to vote. They were driven by both the promise of change, but also in some cases by their anxieties about the future. Much had changed since their campaign began, the US was now more industrial than not, increasingly more urban than rural. The activism and activities of these new urban denizens also gave rise to a new American culture.

American YAWP. (n.d.) Women’s Movements. Retrieved September 2, 2017 from http://www.americanyawp.com/text/20-the-progressive-era/

How It Began: Betty Friedan and the Modern Women’s Movement

Women’s Rights activist, Muriel Fox, discusses the origins of the modern women’s movement, her role in NOW, and her collaboration with Betty Friedan.

“How It Began: Betty Friedan and the Modern Women’s Movement” is licensed under CC BY 3.0 at https://youtu.be/GjVoqZJc5mY

Summary

The legacy of the women’s movement can be traced through women’s roles in society and, specifically, in the workforce. In addition to gaining the right to vote with the 19th amendment, women saw gains in politics as Jeanette Rankin was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1916. It took nearly 65 years for the first female Supreme Court Justice to be appointed in Sandra Day O’Connor but recently expanded to include presidential candidates. Hillary Clinton was chosen as the Democratic candidate for President in 2016.

Increased access to education has also made an impact. The percentage of women in college continues to grow and as of 2009, more women than men earned Ph.D.’s. Greater college attendance links to greater earning potential. Women have moved from mainly nurturing or supportive roles such as teaching and nursing to professional careers culminating in the highest offices. Female entrepreneurs and business owners are also on the rise.

Progress continues to be made or decisions reaffirmed in all facets of the law and legal system. In 1986 the Supreme Court ruled that sexual harassment was, in fact, a form of illegal job discrimination. Yet in 1992, the Supreme Court had to reaffirm Roe v. Wade by striking down Pennsylvania’s Abortion Control Act which sought to reinstate restrictions that were previously ruled unconstitutional. In education, women were admitted to the all-male Virginia Military School in 1996 after the Supreme Court ruled that creating a separate, all-female school would not suffice and in order to continue to receive federal funding the school must admit women. The Lily Ledbetter Fair Pay Restoration Act passed in 2009 and signed by President Barack Obama offered an alternative to reporting pay discrimination in order to protect the victim. And as of January 2, 2016 all jobs in the armed services are now open to women so long as they meet the performance standards, which are gender neutral.