Chapter 25: May – Existential Psychology

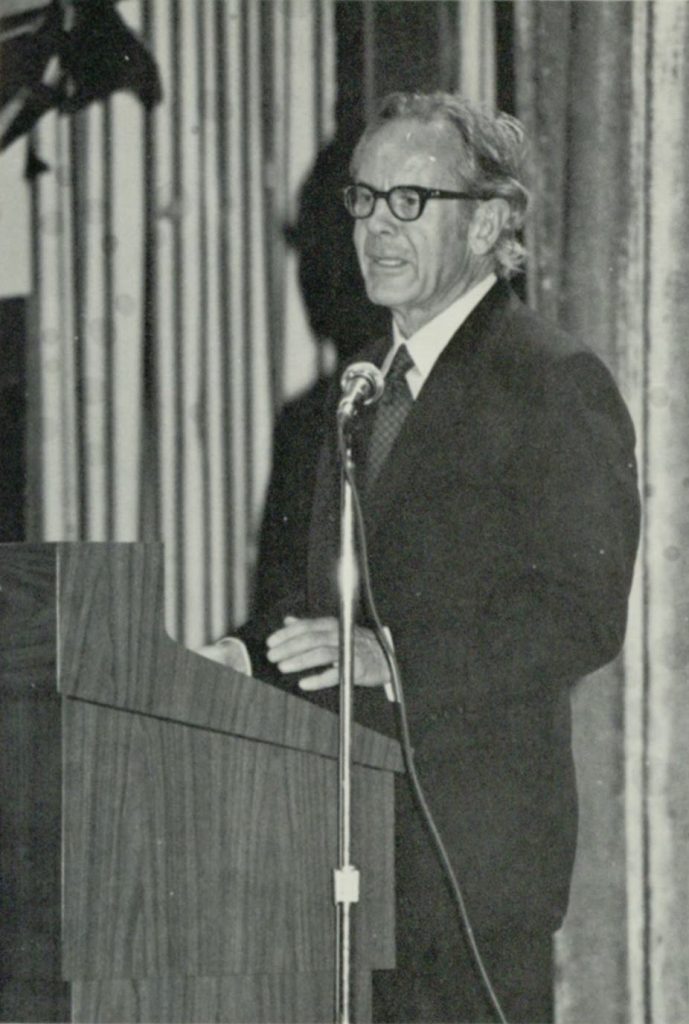

Part 1: Rollo May

Rollo May (1909-1994) introduced existentialism to American psychologists, and he has remained the best known proponent of this approach in America. Trained in a fairly traditional format as a psychoanalyst, May considered the detachment with which psychoanalysts approached their patients as a violation of social ethics. For example, if a psychoanalyst helps a patient to be the best they can be, and the person happens to earn their living in an unseemly or criminal way, it hardly seems proper (Stagner, 1988). On the other hand, who is to decide which values should be preferred in a particular society? In the pursuit of freedom, May suggested that sometimes individuals might reasonably oppose the standards or morality of their society. Politics, a wonderful topic for lively debates, is dependent on opposing viewpoints. Only when an individual lives an authentic life, however, should their opinion be considered valid, and existential psychology seeks to help individuals live authentic lives.

A Brief Biography of Rollo May

Rollo Reese May was born on April 21, 1909, in Ohio, and grew up in Marine City, Michigan. He attended Oberlin College in Ohio, graduating in 1930. Having always been interested in art and artistic creativity, he joined with a small group of artists and traveled to Europe, where they studied the local art of Poland. In order to remain in Europe, May took a teaching position with the American College at Salonika in Greece. When not teaching, he traveled widely throughout Greece, Poland, Romania, and Turkey. He attended the summer school taught by Alfred Adler. Deeply impressed by Adler (as Frankl had been), he nonetheless considered Adler’s theories overly simplistic and too general. This may well have been due to his awakening awareness of the tragic side of human life, keeping in mind that much of Europe suffered greatly during the depression between World War I and World War II (Reeves, 1977).

Upon returning to the United States, May worked as a student advisor and the editor of a student magazine at Michigan State University. In 1936, he enrolled at Union Theological Seminary in New York, with the intention of asking, and most likely hoping to find answers to, the ultimate questions about human life. Despite having no particular desire to become a minister, he did serve in a parish in Montclair, New Jersey for a while. While at the seminary, he became a lifelong friend of Paul Tillich, a well-known existential theologian. Tillich, whose classes May regularly attended, introduced May to the works of Kierkegaard and Heidegger. May also met Kurt Goldstein during this time, and became acquainted with Goldstein’s theories of self-actualization and anxiety as a reaction by organisms to catastrophic events. Regarding his time as a minister, May reflected that the only events which seemed to include an element of reality were the funerals (Reeves, 1977).

Shortly after graduating from the seminary, May began writing books on counseling and creative living. He worked as a counselor at the College of the City of New York, and trained as a psychoanalyst at the William Alanson White Institute of Psychiatry, Psychoanalysis, and Psychology in New York. His time at the training institute overlapped with Harry Stack Sullivan being the president of the William Alanson White Foundation, and Erich Fromm as a fellow associate. In 1946, May began a private practice in psychoanalysis, in 1948 he became a faculty member at the institute, and in 1949 he received the first Ph.D. in clinical psychology at Columbia University. His doctoral dissertation was published as The Meaning of Anxiety (May, 1950), a book that heavily cites the work of Freud and Kierkegaard on anxiety, as well as Fromm, Horney, and Tillich (May, 1950; Reeves, 1977).

Similar to Viktor Frankl, May’s life had taken a dramatic turn during this time, an uncontrollable event that threatened his life: May contracted tuberculosis. At the time, there were no effective treatments for this contagious disease, many people died from it, and like many others, May had to spend several years at a sanitarium (Saranac Sanitarium in upstate New York). It was during his time in the sanitarium that May theorized about anxiety and came to one of the most important conclusions in his career. He determined that although Freud had done a masterful job of characterizing the effects of anxiety on the individual, it was Kierkegaard who had truly identified what anxiety is: the threat of becoming nothing. From this point on, May could clearly be identified as an existential psychologist. He collaborated with Abraham Maslow, Carl Rogers, and Gordon Allport to present a symposium on existential psychology, in conjunction with the 1959 annual convention of American Psychological Association, which led to the publication of a book on the subject (Reeves, 1977).

As May’s career continued, he became a supervisory and training analyst at the William Alanson White Institute, and an adjunct professor of psychology in the graduate school at New York University. He gave a series of radio talks on existential psychology on a Canadian Broadcasting Corporation show, he served as a visiting professor at Harvard and Princeton, and he continued writing. His later books include works on dreams, symbolism, religion, and love. He eventually settled in California, where he died in 1994.

Supplemental Materials

This video [10:15] provides an introduction to the work of the American psychologist Rollo May, with an emphasis on his social critique and his vision of existential psychotherapy.

Source: https://youtu.be/wms_RXEta5c

References

Text: Kelland, M. (2017). Personality Theory. OER Commons. Retrieved October 28, 2019, from https://www.oercommons.org/authoring/22859-personality-theory. Licensed under CC-BY-4.0.

Eric Dodson. (2014, March 2014). Rollo May in ten minutes. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/wms_RXEta5c. Standard YouTube License.