Chapter 2: Freud – Psychoanalysis

Part 3: Structure of Personality

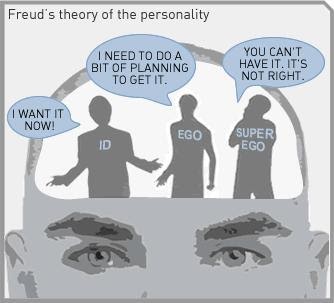

It is no accident that our discussion of the id, ego, and superego follow immediately after our discussion of the levels of consciousness. In The Ego and the Id (which also discuss the superego, despite not including it in the title; Freud, 1923/1960), Freud begins with a chapter on consciousness and what is unconscious, then follows with a chapter on the ego and the id, and then a chapter on the ego and the superego. It is difficult to discuss the two concepts, levels of consciousness and the psychical apparatus (a term Freud used for the id, ego, and superego), without intertwining them. In addition, these three structures begin as one; the ego develops from the id, and later the superego develops from the ego. As with levels of consciousness, it is inappropriate to think of the id, ego, and superego as actual structures within the brain, rather they are constructs to help us understand the psychodynamic functioning of the mind. Freud acknowledged this lack of understanding and went so far as to say that even if we could localize them within the brain, we wouldn’t necessarily be any closer to understanding how they function (Freud, 1938/1949).

Id, Ego, Superego

The oldest aspect of the psyche is the id, which includes all that we inherit at birth, including our temperament and our instincts. The only goal of the id is to satisfy instinctual needs, such as hunger, thirst and sex, and desires; therefore, it acts according to the pleasure principle. It knows nothing of value judgments, no good, no evil, and no morality at all. It does not change or mature over time. According to Freud, there is nothing in the id except instinctual cathexes seeking discharge (Freud, 1933/1965). The energy associated with these impulses, however, is different from other regions of the mind. It is highly mobile and capable of discharge, and the quality of the discharge seems to be disregarded. This is a very important point, because it means that the id does not need to satisfy its desires in reality. Instead, they can be satisfied through dreams and fantasy.

Because the id demands satisfaction and knows nothing of restraint, it is said to operate as a primary process. Since it can be satisfied in unreal ways, if we examine phenomena such as fantasies and dreams we can uncover the nature of the id. It was during his studies on dream-work that Freud developed his understanding of the primary process of the id (Freud, 1923/1960). Actually, we can only know the id through psychoanalysis, since it exists entirely within the unconscious mind. Therefore, we need a secondary process structure in order for the mind to interact with the external world. This structure is found in the ego.

The ego arises from the id as an intermediary between the id and the external world. The ego functions according to the reality principle, and tries to bring the external world to bear on the impulses of the id. In other words, as the id demands satisfaction, it is hindered by the reality of our environment and our societal and cultural norms. The ego postpones satisfaction until the time or the circumstances are appropriate, or it may suppress the id impulses altogether (Freud, 1938/1949). Freud believed that the ego is associated with perception (of reality) in the same way that the id is associated with instinct. The id is passionate, whereas the ego represents reason and common sense. But the id has the energy, the libido, to demand its satisfaction in some way, and the ego can only derive its energy from the id. Freud likened the ego to a horseback rider on a horse named id. The rider cannot always control the far more powerful horse, so the rider attempts to transform the will of the horse as if it were the rider’s own will (Freud, 1923/1960).

The ego develops in part because it is that portion of the mind impacted by sensory input from the external world. Therefore, it resides partially in the conscious mind, and must serve three tyrannical masters: the id, the external world, and the superego (which we will discuss below). The goals of these three masters are typically at odds with one another, and so the ego’s task is not an easy one (Freud, 1933/1965). The ego approaches this task by monitoring the tension that exists within the mind. This tension arises from internal and external stimuli making demands upon the mind, lowering this tension is felt as pleasurable, and increasing the tension is unpleasant. The id demands immediate reduction of tension, in accordance with its pleasure principle, whereas the ego seeks an appropriate reduction of tension, in accordance with its reality principle. A key point, of course, is that the ego also seeks pleasure. It does not try to deny the impulses of the id, only to transform or delay them. But why does the ego even bother to do that? There are times when pursuing pleasure can get us in serious trouble, but there are also times when we make choices because they seem right to us. These decisions, based on justice, morality, humanism, whatever term you choose, are mediated by the superego.

According to Freud, the superego is heir to the Oedipus complex, and arises as the child abandons their intense attachment to their parents. As a replacement for that attachment, the child begins to identify with their parents and so incorporates the ideals and moral values of their parents and later, teachers and other societal role models (Freud, 1933/1965). According to this view, the superego cannot fully develop if the child does not resolve the Oedipus complex, which, as we will discuss below, cannot happen for girls. The superego functions across all levels of the conscious and unconscious mind.

The superego takes two forms: an ego-ideal and a conscience. Freud considered the term ego-ideal as an alternative to the term superego, and it is not until we incorporate the development of conscience that we can recognize ego-ideal and conscience as different aspects of the superego. The development of the superego is a complicated process and seems to derive from the development of the ego itself. For an infant, the attachment to the parents and identification with them is not recognized as something different. The ego is weak and can do little to restrain the id. As the child grows, the erotic nature of the love for the mother is slowly transformed into identification; the ego grows stronger, and begins to become associated with being a love-object itself. When the ego is capable of presenting itself to the id as an object worthy of love, narcissistic libido is generated and the ego becomes fully formed (Freud, 1923/1960). In other words, the child becomes an individual, aware that they are separate from their parents. There is still an intense attachment to the mother, however, which stems from the early days of breastfeeding. The child must eventually lose this intense attachment to the mother and begin to more fully identify with either the father (for boys) or the mother (for girls). As noted above, this final transformation from attachment to identification should occur during the Oedipus complex, and the ego-ideal arises within the context of the child knowing “I should act like my father” (for boys) or “I should act like my mother” (for girls).

Although the ego-ideal could represent the culmination of development, Freud believed that one more step came into play. Because of the difficulty the child encounters during the loss of the intense, erotic desires of the Oedipus complex, Freud felt there was more than simply a residue of those love-objects in the mind. He proposed an energetic reaction-formation against the earlier choices. Now, the child incorporates concepts of “I must not act like my father or mother.” Under the influences of authority, schooling, religion, etc., the superego develops an ever stronger conscience against inappropriate behavior. This conscience has a compulsive character and takes the form of a categorical imperative (Freud, 1923/1960). This conscience is our knowledge of right and wrong, and early on it is quite simplistic. There is right and there is wrong (as with Kohlberg’s earliest stages of moral development; Kohlberg, 1963).

Supplemental Materials

This video [5:29] aims to describe the id, ego and superego by offering examples and metaphors to help differentiate the concepts.

Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WRtItnRRV1M

References

Text: Kelland, M. (2017). Personality Theory. OER Commons. Retrieved October 28, 2019, from https://www.oercommons.org/authoring/22859-personality-theory. Licensed under CC-BY-4.0.

PsychU. (2017, July 13). id, ego, & superego. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WRtItnRRV1M. Standard YouTube License.

Anxiety

We have already taken a look at the challenges faced by the ego in trying to balance the demands of the id, the superego, and the external world. What happens when the demands of these conflicting elements become too much for the ego to deal with? Simply put, we get scared, we experience fear and anxiety as a signal that there is some impending danger. Only the ego can experience anxiety, even if the underlying cause begins with the id or superego. Anxiety arises primarily from libido that has not been utilized. For example, if we are frustrated from fulfilling some id impulse, such as needing to go to the bathroom in the middle of a great movie, the libido is charged yet no release is experienced. This creates tension and the corresponding unpleasant feelings. As the id demands satisfaction, but the ego cannot figure out how to satisfy the id (and you really don’t want to miss the good part of the movie), the fear arises that the id will satisfy itself. Most of us would consider the possibility of going to the bathroom in our pants while at a movie a real danger to our self-esteem, and we could be arrested if we simply went to the bathroom right there in the movie theater. As the ego is reduced to helplessness in its inability to find a reasonable outlet for the impulse of needing to go to the bathroom, anxiety serves the useful and important purpose of warning the ego that the impulse must be satisfied in order to avoid the danger (Freud, 1926/1959). And in support of Freud’s view regarding our sexual nature, who would deny the great pleasure felt upon finally getting to the bathroom?

Freud described three general types of anxiety. Realistic anxiety involves actual threats to our physical safety. It is similar to fear in that there is a real and external object that could harm us, but it differs from fear in that we may not be aware of a specific danger. For example, after the famous book Jaws (Benchley, 1974) was made into a movie (the kind of movie that you don’t want to miss the good scenes), many people became anxious about swimming in the ocean, even though there were no specific sharks for them to fear. Still, there are sharks in the ocean, so it might be reasonable to experience some anxiety. Sometimes we are anxious about a real danger, but the anxiety we experience is completely out of proportion in relation to the threat. This suggests that there is an element of neurotic anxiety accompanying the realistic anxiety (Freud, 1926/1959).

Neurotic anxiety generally arises from an internal danger, the threat that unacceptable id impulses will break through and be acted on by the individual. The ultimate danger that exists is that we really will be harmed as a result of our actions. Therefore, Freud considered there to be a close association between neurotic and realistic anxiety (Freud, 1926/1959). For example, if we are being harassed by a bully, our aggressive id impulse might be to respond by killing this bully. Of course, that could result in going to prison or having the bully’s friends kill us. So the anxiety that our violent id impulse might break out and influence our behavior is associated with the real danger posed by the consequences of that behavior, if it should happen to occur. Therefore, our neurotic anxiety is composed, in part, of our internalized realistic anxiety.

In a similar way, moral anxiety arises from conflict between our ego and the constraints imposed on it by the superego. Since the superego arises from the internalization of our parent’s teaching us what is or is not appropriate behavior, we again have an association between the internal threat of the superego and the real, external threat of being punished by our parents. Therefore, as with neurotic anxiety, the precursor to our moral anxiety is realistic anxiety, even if our fears are based on our psychological impressions of a situation as opposed to an actual danger (e.g., the fear of castration; Freud, 1926/1959, 1933/1965).

Freud also described an overall pattern to the development and expression of anxiety and its useful role in life. In early childhood, we experience traumatic situations in which we are helpless. Remember that Freud believed that psychic reality is every bit as significant as actual reality (Freud, 1900/1995), so the nature of these traumatic events is subject to individual perception. As the child’s capacity for self-preservation develops, the child learns to recognize dangerous situations. Rather than waiting passively to be threatened or harmed, an older child or an adult will respond actively. The initial response is anxiety, but anxiety is a warning of danger in anticipation of experiencing helplessness once again. In a sense, the ego is recreating to the helplessness of infancy, but it does so in the hope that now the ego will have at its command some means of dealing with the situation. Therefore, anxiety has hopefully transformed from a passive response in infancy to an active and protective response in later childhood and/or adulthood (Freud, 1926/1959).

Supplemental Materials

Freudian Defense Mechanisms (Intro Psych Tutorial #131)

This video [13:19] describes several of the defense mechanisms theorized by Sigmund Freud and his daughter Anna Freud. These defense mechanisms provide ways of coping with anxiety, which could be reality anxiety, neurotic anxiety, or moral anxiety.

Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jfOGC-8KndQ

References

Text: Kelland, M. (2017). Personality Theory. OER Commons. Retrieved October 28, 2019, from https://www.oercommons.org/authoring/22859-personality-theory. Licensed under CC-BY-4.0.

PsychExamReview. (2017, July 16). Freudian defense mechanisms (Intro Psych Tutorial #131). [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jfOGC-8KndQ. Standard YouTube License.

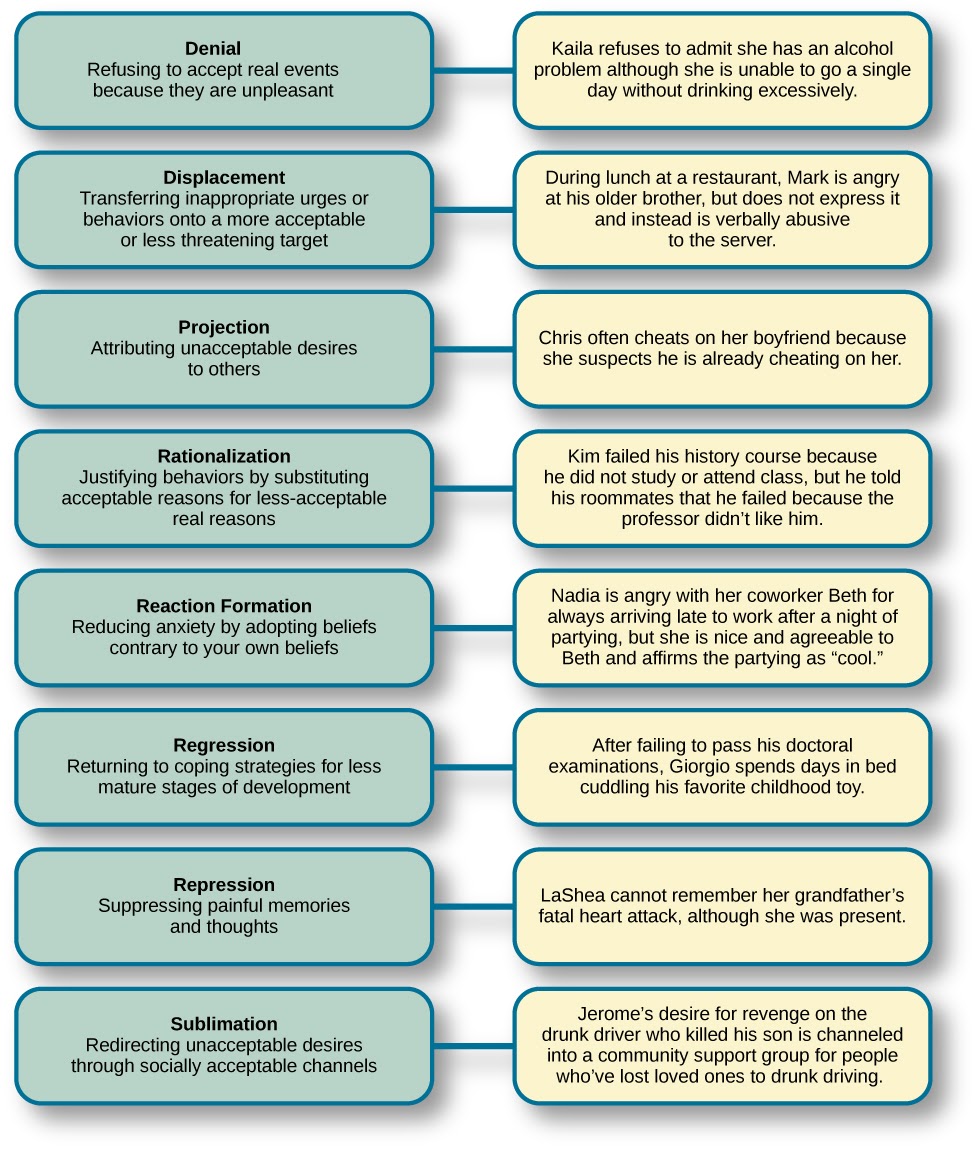

Defense Mechanisms

Freud believed that feelings of anxiety result from the ego’s inability to mediate the conflict between the id and superego. When this happens, Freud believed that the ego seeks to restore balance through various protective measures known as defense mechanisms. When certain events, feelings, or yearnings cause an individual anxiety, the individual wishes to reduce that anxiety. To do that, the individual’s unconscious mind uses ego defense mechanisms, unconscious protective behaviors that aim to reduce anxiety. The ego, usually conscious, resorts to unconscious strivings to protect the ego from being overwhelmed by anxiety. When we use defense mechanisms, we are unaware that we are using them. Further, they operate in various ways that distort reality. According to Freud, we all use ego defense mechanisms.

While everyone uses defense mechanisms, Freud believed that overuse of them may be problematic. For example, let’s say Joe Smith is a high school football player. Deep down, Joe feels sexually attracted to males. His conscious belief is that being gay is immoral and that if he were gay, his family would disown him and he would be ostracized by his peers. Therefore, there is a conflict between his conscious beliefs (being gay is wrong and will result in being ostracized) and his unconscious urges (attraction to males). The idea that he might be gay causes Joe to have feelings of anxiety. How can he decrease his anxiety? Joe may find himself acting very “macho,” making gay jokes, and picking on a school peer who is gay. This way, Joe’s unconscious impulses are further submerged.

There are several different types of defense mechanisms. For instance, in repression, anxiety-causing memories from consciousness are blocked. As an analogy, let’s say your car is making a strange noise, but because you do not have the money to get it fixed, you just turn up the radio so that you no longer hear the strange noise. Eventually you forget about it. Similarly, in the human psyche, if a memory is too overwhelming to deal with, it might be repressed and thus removed from conscious awareness (Freud, 1920). This repressed memory might cause symptoms in other areas.

Another defense mechanism is reaction formation, in which someone expresses feelings, thoughts, and behaviors opposite to their inclinations. In the above example, Joe made fun of a homosexual peer while himself being attracted to males. In regression, an individual acts much younger than their age. For example, a four-year-old child who resents the arrival of a newborn sibling may act like a baby and revert to drinking out of a bottle. In projection, a person refuses to acknowledge her own unconscious feelings and instead sees those feelings in someone else. Other defense mechanisms include rationalization, displacement, and sublimation.

Supplemental Materials

Sigmund Freud and Defense Mechanisms (Psychology)

This video [6:31] reviews Freud’s various defense mechanisms, providing an example for each.

Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rWAJ58aqHjY

References

Text: OpenStax College. (n.d.) Psychology. Retrieved from https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wsu-sandbox/chapter/freud-and-the-psychodynamic-perspective/#Figure_11_02_Defense. Licensed under CC-BY-4.0.

David Franklin. (2016, February 23). Sigmund Freud and Defense Mechanisms (Psychology). [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rWAJ58aqHjY. Standard YouTube License.